20.10.2021

SpaceX’s first orbital Starship launch slips to March 2022 in NASA document

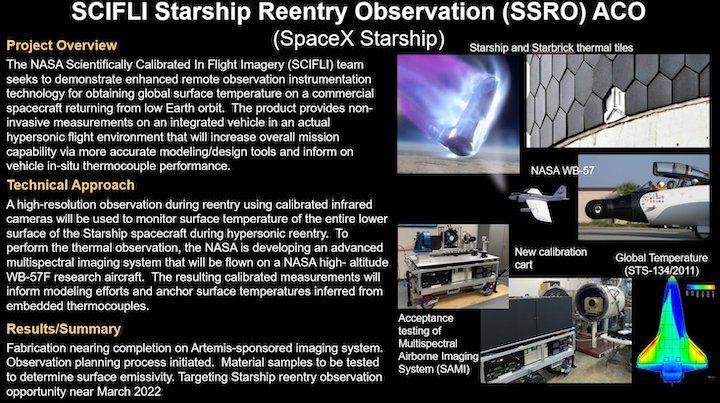

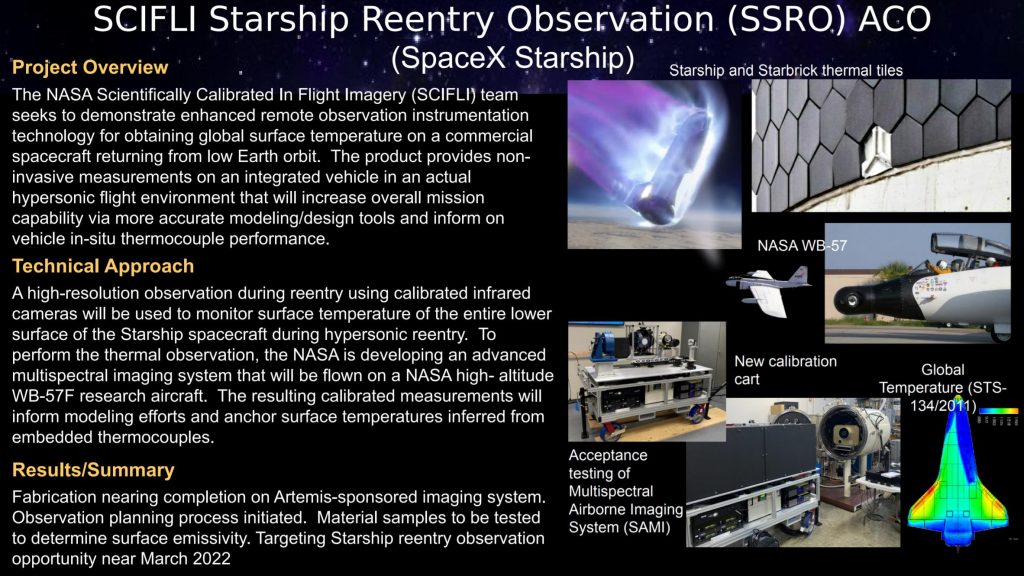

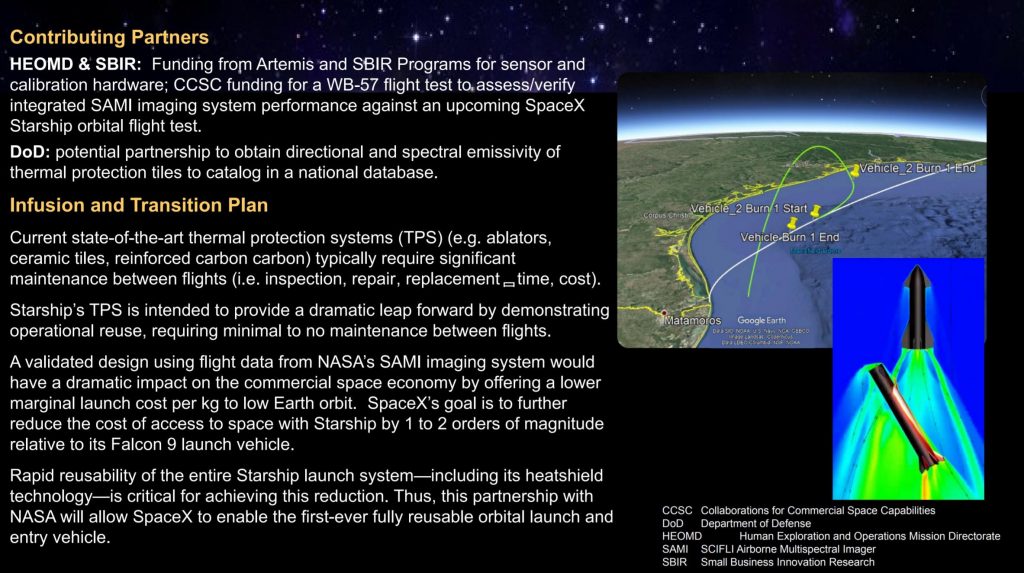

A NASA document discussing a group’s plans to document SpaceX’s first orbital-velocity Starship reentry appears to suggest that the next-generation rocket’s orbital launch debut has slipped several months into 2022.

In March 2021, CEO Elon Musk confirmed a report that SpaceX was working towards a target of July 2021 for Starship’s first orbital launch attempt. At the time, it seemed undeniably ambitious but far from impossible. Less than half a year prior, SpaceX had kicked off a series of suborbital Starship test flights to altitudes of 10-12.5 km (6.2-8 mi). Beginning in December 2020, SN8 – effectively the first structurally complete Starship prototype – nearly stuck a landing on its first try, only narrowly falling short due to an engine and pressurization issue.

Less than two months later, SpaceX completed and launched Starship SN9 – again with a nearly flawless six-minute flight capped off with an unsuccessful landing attempt. Starship SN10 followed less than a month later and became the first prototype to land in one piece – albeit only for a few minutes. It was two weeks after that near-success – SpaceX’s third launch in as many months – that Musk revealed a goal of July 2021 for Starship’s first orbital launch. At that point in time, it appeared all but inevitable that SpaceX would be technically ready for an orbital launch before the end of the year.

+++

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cjq85zVUW7A&t=94s

Two weeks after Musk’s comments and less than four weeks after SN10’s near-miss, Starship SN11 gave one of the worst performances yet, invisibly exploding inside a fogbank well above the ground. However, further stoking the fires of optimism, Starship SN15 debuted a number of upgrades and became the first prototype to successfully launch, land, and survive a ~10km test flight in early May. Put simply, SpaceX built five Starship prototypes practically from scratch in roughly eight months and then completed five test flights in less than five months – all of which were largely successful.

SpaceX considered reusing Starship SN15 or launching SN16 to gain more landing experience but ultimately decided to mothball the prototypes to avoid disrupting orbital launch site construction. Just three months after SN15’s successful landing, SpaceX rolled the first orbital-class Starship and Super Heavy to the orbital launch site and briefly stacked the pair (Ship 20 and Booster 4) to their full height, forming the tallest rocket ever assembled. Although largely a photo opportunity, SpaceX still installed a full 29 Raptors on Super Heavy B4 and six Raptors on Starship S20, further raising confidence that the company’s engine production was already up to the task of supplying the nearly three-dozen needed for a single orbital test flight.

However, for reasons that are less than clear, that August 6th full-stack milestone is about where SpaceX’s H1 2021 momentum appeared to run into a brick wall. Perhaps due to a desire to focus on orbital launch site construction even at the cost of avoiding road closures or testing that would require a clear pad, Starship S20 sat on a stand for the better part of two months before completing even a minor test – by far the longest any Starship prototype has waited.

Seemingly in the midst of its third round of Raptor engine removal, Super Heavy B4 has yet to attempt a single test and it’s unclear how close to ready the orbital pad is to support booster proof and static fire tests. Neither ship nor booster has attempted to static fire its Raptor engines, though S20 could potentially be ready for its first test as early as Monday, October 18th.

Combined with recent developments in the FAA’s Boca Chica environmental review process, the odds of SpaceX attempting the first orbital Starship launch by the end of 2021 have rapidly dropped from decent to near-zero. From a technical perspective, it seems likely that SpaceX could still be ready for an orbital launch attempt just a few months from now. From a regulatory perspective, though, it would be practically unprecedented for the FAA to complete a favorable environmental review andapprove even a one-off orbital Starship launch license in ~10 weeks. Even the apparent March 2022 target revealed in a NASA poster focused on the agency’s plans to film an orbital Starship reentry via high-altitude jet assumes that the FAA’s review and licensing process will take ~7 months from August 2021 – still extremely optimistic.

Ultimately, after two months with next to no prototype testing, it’s beginning to look like SpaceX has decided to focus on finishing Starbase’s first orbital launch site, refining vehicle designs, and building new prototypes (B5, S21, S22) rather than pushing hard for rapid B4/S20 testing and an imminent launch attempt. As a result, it’s becoming increasingly unlikely that Booster 4 and Ship 20 will fly as new and improved prototypes like Super Heavy B5 and Starship S21 prepare to overtake them.

Quelle: TESLARATI

----

Update: 22.10.2021

.

SpaceX rolls second-to-last ‘cryoshell’ to Starbase’s orbital tank farm

In the last two days, SpaceX has transported a giant mystery tank and the second-to-last ‘cryoshell’ to Starbase’s orbital tank farm, pushing Starship’s first orbital-class launch site a step closer to completion.

While the horizontal tank moved to the pad on Sunday remains decidedly mysterious, the ‘cryoshell’ is a well-understood component of SpaceX’s custom-built solution to Starship and Super Heavy propellant storage. Unlike virtually all other modern orbital launch sites, including SpaceX’s three Falcon pads and suborbital Starship test site, the company decided to build its first orbital-class Starship tank farm more or less from scratch. Though the number of off-the-shelf tanks continues to increase in recent weeks, the farm’s primary tanks – tasked with storage thousands of tons of liquid oxygen and methane propellant and liquid nitrogen coolant – are essentially stretched and lightly modified Starships.

Built in the same Starbase facilities with the same techniques and out of the same parts as Starship tanks, SpaceX’s custom storage tanks are likely cheaper than alternatives. However, they still amount to thin, uninsulated steel tanks – about as bad a vessel as it gets for the stable storage of cryogenic fluids. To solve the problem of insulation, SpaceX split the difference between pure vertical integration and a pure off-the-shelf solution and contracted with a third party to build massive ‘cryoshells’ – 12m (~40 ft) wide cylinders that ‘sleeve’ SpaceX’s custom 9m (~30 ft) wide storage tanks.

For the first of several anticipated orbital Starship launch pads and tank farms, that contractor built eight shells for SpaceX – seven sleeves and one million-gallon water tank. Over the last six months, SpaceX has installed the water tanks, completed all seven custom-built propellant storage tanks, and ‘sleeved’ five of those tanks. Beginning in September, two or three of the five sleeved tanks have even graduated into cryogenic proof testing.

Just days ago, SpaceX also began delivering liquid oxygen (LOx) to the orbital tank farm for the first time ever, suggesting that the company has begun the slow process of filling one, two, or even all three of the farm’s LOx tanks with a small army of tanker trucks.

On Monday, October 18th, SpaceX rolled the first of the last two remaining cryoshells from their build site to the orbital tank farm. Hours later, SpaceX attached a crane, lifted the sixth cryoshell, and sleeved GSE tank #8 – the second of two methane tanks. With that installation out of the way, there’s now a good chance that Starship’s first orbital tank farm will be structurally complete by the end of the month. With a vast majority of plumbing already in place and the process of filling the spaces between cryoshells and GSE tanks with insulating foam already underway, it’s possible that the farm will be ready to support some level of Super Heavy wet dress rehearsal and static fire testing sometime next month.

In the meantime, there remains the mystery of a pair of massive horizontal liquid methane (LCH4) tanks – the first of which was installed at the orbital tank farm on Sunday, October 17th. Likely capable of holding about as much fuel as each of SpaceX’s two custom-built LCH4 storage tanks, it’s unclear why the company appears to be effectively doubling the orbital pad’s LCH4 storage capacity with the addition of two new tanks purchased off the shelf.

Quelle: TESLARATI

----

Update: 17:34 MESZ

.

SpaceX Starship Raptor vacuum engine fired for the first time

The RVac gets its first showing while strapped to the bottom of a Starship in delightful dusk test fire.

SpaceX, Elon Musk's spaceflight juggernaut, is in the middle of a lengthy licensing process with the Federal Aviation Administration over whether it will be able to launch its mammoth Starship to orbit from the coast of Boca Chica, Texas. In the meantime, it's carrying on its merry way, testing out a variant of its super-powered Raptor engine.

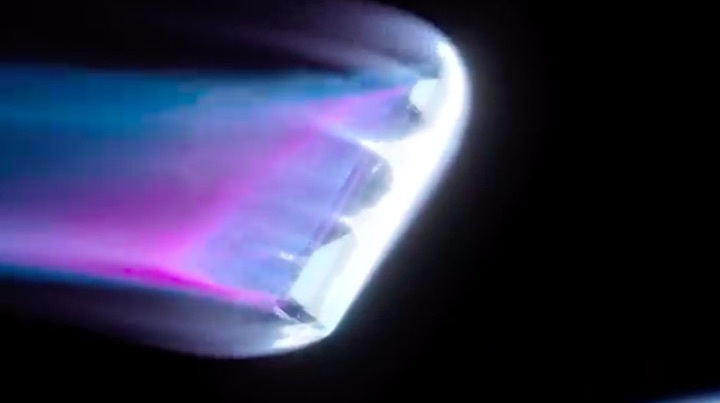

On Thursday, SpaceX shared a video of its Raptor vacuum engine -- integrated onto a Starship prototype -- firing for the first time in the dusk light at Starbase on the Texas coast. While it's technically the second time the vacuum has been tested, it's the first time SpaceX has done so while the engine is attached to the rocket.

Starship is intended to carry humans to the moon and, eventually, Mars. The Raptor vacuum (or "RVac") engine is basically a "space" version of the Raptor engines that will lift off from Earth underneath the Super Heavy booster.

The vacuum engines have a much larger nozzle and are designed to operate more efficiently in the vacuum of space than the "sea-level" version of Raptor. Starship is expected to be outfitted with three RVacs and three standard Raptor engines for flights across the solar system.

You can see the test firing below.

A second static test fire was reported by Space.com later in the evening.

There's still a long way to go before SpaceX gets Starship to orbit. After a bunch of successful test flights (including some that ended explosively) reached a height of around 6 miles (10 kilometers), SpaceX has been preparing for the next prototype flight. But the FAA is currently seeking public comments on a draft of the FAA's Environmental Assessment, which is required under the National Environmental Policy Act, before the agency can grant SpaceX a launch license for the first orbital flight of Starship.

That period is expected to end on Nov. 1 and then the FAA will publish a final assessment. If the Administration asks for a full Environmental Impact Statement, we might be seeing a lot more test firings on the ground.

Quelle: Cnet

Musk says Starship may be ready for orbital launch next month, but FAA review continues

Elon Musk, the billionaire founder of SpaceX, said Friday the company’s huge new Starship rocket could be ready for its first orbital test launch from South Texas as soon as November, but the schedule comes with two big uncertainties that may push the launch to next year.

“If all goes well, Starship will be ready for its first orbital launch attempt next month, pending regulatory approval,” Musk tweeted.

The new schedule update from Musk came the day after SpaceX test-fired the newest Starship vehicle, known as Ship 20 or SN20, at the company’s development facility near Boca Chica Beach east of Brownsville, Texas. A vacuum-rated Raptor engine, similar to the engines Starship will use in space, ignited for several seconds on a launching stand at SpaceX’s Starbase complex Thursday night.

SpaceX briefly fired the privately-developed rocket again later the same night.

It was the first test-firing of a Raptor vacuum engine mounted to a Starship rocket. The vacuum variant of the methane-fueled Raptor engine has a larger nozzle to improved performance in the airless environment of space.

Three vacuum-rated Raptor engines will fly on orbital-class Starship missions. Three sea level Raptor variants, with smaller nozzles, will be used for vertical Starship landings after returning from space.

Unlike the Starship prototypes flown on the recent atmospheric hops, Ship 20 is covered in thousands of heat-resistant tiles to protect the craft’s stainless steel structure from the scorching heat it will encounter during re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere.

The Starship will launch on top of a huge reusable first stage booster called the Super Heavy. Made of stainless steel, the entire stack stands 394 feet (120 meters) tall, higher than any rocket ever built.

Fitted with up to 33 Raptor engines, the Super Heavy will propel the Starship into space with twice the thrust of NASA’s Apollo-era Saturn 5 moon rocket, and nearly double the power of NASA’s Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket.

In August, SpaceX teams in South Texas briefly stacked the entire Starship rocket on a launch mount for a fit check and photo opportunity. At the time, SpaceX connected 29 Raptor engines — four fewer than the booster will use on an operational flight — to the Super Heavy and rolled the booster to the ever-expanding launch complex, just east of the company’s build site.

After the fit check, SpaceX removed the Raptor engines from the Super Heavy, designated Booster 4, as attention turned to preparing Ship 20 for cryogenic proof testing in September.

SpaceX then readied Starship for its first static fire tests this week. More test-firings may occur before Ship 20 is mounted on top of the Super Heavy booster again.

Meanwhile, SpaceX plans to perform cryogenic proof testing of Booster 4 some time in the coming weeks, likely followed by a series of test-firings, culminating in a static fire with its full complement of Raptor engines.

Outfitting of the launch pad tower at Boca Chica has also continued since its initial construction over the summer. Earlier this week, crews lifted massive arms, nicknamed “chopsticks,” onto the launch tower that SpaceX aims to use for catching descending Super Heavy boosters.

Although SpaceX has moved forward with great speed at Boca Chica, the chances of the Super Heavy and Starship vehicles being ready for flight next month are uncertain. Musk often sets aspirational schedule goals, and in September 2019 said he wanted to attempt the first orbital launch attempt with Starship within six months.

Another schedule hurdle might be the Federal Aviation Administration, which is reviewing the environmental impacts of SpaceX’s operations in South Texas. The FAA issued a draft environmental report last month after consultation with several federal and state agencies.

The draft report marks a re-evaluation of the FAA’s original environmental impact statement before SpaceX started construction of the Boca Chica site in 2014. At that time, SpaceX planned to launch Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets from South Texas, but the scope of the project has since changed to focus on development of Starship and Super Heavy.

The FAA held public hearings Monday and Wednesday, and some 120 people voiced their opinions on the project’s environmental impacts. The public comments were more than two-to-one in favor of the FAA finalizing the draft programmatic environment assessment, and issuing SpaceX a launch license for the Starship orbital test flight.

Many of the comments in favor of SpaceX came from members of the public outside Texas. The share of people who identified themselves as local residents and voiced opposition was higher.

Joyce Hamilton, who said she was a member of the local community, worried that SpaceX would damage the “fragile and unique coastline” at Boca Chica Beach.

“In fact, we’ve already seen the damaging impact of a recent launch failure with a wide and destructive debris field along the beach and surrounding wetlands,” Hamilton said. “I’d like to just end by urging the FAA to conduct a serious comprehensive environmental impact study.”

Rebecca Hinojosa, a Brownsville resident, said SpaceX has been a destructive influence on the community through gentrification, and displaced residents who once lived near the Boca Chica site. SpaceX bought out homes in the area as it constructed the facility.

Others were supportive of the FAA allowing SpaceX to go ahead with no delay, citing the positive economic effects of SpaceX’s presence in the Rio Grande Valley.

“Elon Musk chose our community to be the next home of his SpaceX operation, and very, very quickly after setting up, this area went from being one of the poorest areas, one of the most looked-down, in the entire nation … We’re no longer in that position. We’re now one of the most sought after zip codes to live and raise your children,” said Jessica Tetreau, a Brownsville city commissioner.

“I don’t just ask you,” she concluded. “I beg you to give them that permit.”

“As far as the environment goes, it seems to me that SpaceX has a good plan in place to mitigate the vast majority of environmental effects from the build and test sites,” said Michael O’Halloran, who did not identify himself as a local resident. “Starship and Super Heavy are clearly worth the gamble.”

The FAA is accepting written comments until Nov. 1, then will determine whether to finalize the draft environmental assessment or begin a new environmental impact statement if the environmental effects would be significant and could not be properly mitigated.

A new environmental impact statement would take months, or even years, to complete.

A decision by the FAA on which route to take is not expected immediately. The FAA said it is reviewing the environmental impacts from SpaceX’s Starship launch and re-entry operations, debris recovery, the launch pad integration tower and other launch-related construction, and local road closures at Boca Chica.

SpaceX can’t launch the Starship and Super Heavy vehicle until the FAA issues a license, which will only come after the completion of the environmental process.

NASA awarded SpaceX a contract to develop a version of the Starship rocket as a human-rated lander for the agency’s Artemis moon missions.

That contract award is currently on hold after Blue Origin, the space company founded by billionaire Jeff Bezos, filed suit in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims. A ruling on the lawsuit could come next month.

SpaceX is developing the privately-owned Starship vehicle as a fully reusable launch and space transportation system capable of ferrying more than 100 metric tons of cargo into low Earth orbit, more than any other rocket in the world. SpaceX eventually aims to develop an in-space refueling capability to extend Starship’s heavy-duty cargo carrying range into the solar system.

During an orbital launch attempt, a reusable Super Heavy first stage booster will detach from the Starship and come back to Earth for a vertical landing. For the first orbital mission, SpaceX plans to guide the the booster to a water landing in the Gulf of Mexico.

SpaceX is also modifying offshore oil drilling rigs to serve as floating Starship launch and landing platforms.

The Starship will continue into orbit and deploy its payloads or travel to its deep space destination, and finally return to Earth to be flown again. The Starship vehicle doubles as an upper stage and a refillable transporter to ferry people and cargo through space to destinations in Earth orbit, the moon, Mars, and other distant locations.

The reusable architecture, which builds upon SpaceX’s partially reusable Falcon 9 rocket, is designed to reduce the cost of each flight.

The Starship’s first orbital test flight, though audacious in scale, will aim to prove out the rocket’s basic launch and re-entry capabilities without fully testing out the complicated landing and recovery systems, according to a SpaceX’s filing with the Federal Communications Commission earlier this year.

On the first orbital mission, SpaceX plans for the Starship to re-enter the atmosphere after one trip around Earth, heading for a controlled landing at sea in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii.

SpaceX Starship fires up Raptor Vacuum engine twice in one hour

After weeks of exceptionally cautious buildup, SpaceX’s first orbital-class Starship prototype has repeatedly broken new ground tests in the first few hours of its first static fire test window.

SpaceX first installed Starship S20 on one of two suborbital launch and test stands more than two months ago. After almost six weeks of largely invisible work, longer than any other new Starship prototype has spent inactive at Starbase launch facilities, Ship 20 came to life for the first time during a ‘pneumatic proof’ test completed on September 27th. Two days later, put the Starship through a complex cryogenic proof test, loading supercool liquid nitrogen instead of ambient-temperature gas and simulating the thrust of six Raptor engines with hydraulic rams.

According to CEO Elon Musk, Ship 20 passed its first ‘cryoproof’ without issue, opening the door for static fire testing with real methane and oxygen (LCH4/LOx) propellant and Raptor engines. However, for unknown reasons, it would ultimately take SpaceX more than three weeks of additional work to prepare Starship S20 for its first engine-involved test.

On October 19th, near the end of a seven-hour test window, Starship S20 sort of fired up for the first time, completing what is known as a preburner test. Effectively the first half of static fire test without full ignition, it was nevertheless the first time a Raptor Vacuum engine was operated on a Starship prototype. Originally, based on road closures scheduled with Cameron County, Texas, that preburner test and associated static fire testing was initially scheduled to begin as early as Friday, September 31st.

SpaceX continued to file for and cancel closures throughout the next week, culminating in a few local residents receiving a routine safety notice about a possible test on October 13th. That attempt was canceled soon after and SpaceX ultimately distributed alerts for tests on October 14th and October 18th. Ship 20’s first preburner test was completed on the 19th, followed by another soon-to-be-rescinded notice on the 20th.

Finally, after perhaps the windiest road yet for a Starship from cryoproof to static fire, Starship S20 sailed through a static fire test flow on October 21st and ultimately fired up for the first time ever at 7:16 pm CDT (00:16 UTC). In perfect opposition to weeks of unprecedentedly slow testing, Starship S20 not only completed its first true static fire early in the test window, but it completed the first on-vehicle static fire of a Raptor Vacuum engine and then, just over an hour later, performed a secondstatic fire – this time simultaneously igniting both a Raptor Vacuum and Raptor Center (sea-level-optimized) engine. Aside from also marking the first time that two Raptor variants have been simultaneously fired on the same vehicle, Starship S20’s two-test surprise was technically the fastest back-to-back static fire SpaceX has ever completed, beating Starship SN9 by about 15 minutes.

Back in January 2021, SN9 completed an unprecedented three back-to-back-to-back Raptor static fires in less than 100 minutes as part of what Musk described as “[a day] about practicing Starship engine starts.” SN9 ultimately completed two of those tests in 75 minutes, setting a niche but still impressive turnaround record. Starship S20, however, managed two static fires in 62 minutes on October 21st.

With any luck, Ship 20’s unexpected first-test milestones will mark the start of a more energetic period for the orbital-class prototype, potentially building up to the first Starship static fire with more than three Raptors and the first test with all six engines installed. Super Heavy Booster 4 is also welloverdue for its own proof and static fire test campaign, virtually all of which will be new territory for SpaceX.

SpaceX begins filling Starship’s orbital launch site with rocket propellant

Less than a year after tank farm assembly began in South Texas, SpaceX has begun the painstaking process of filling Starship’s first orbital launch site with thousands of tons of rocket propellant.

Comprised of seven giant custom-built tanks, the last of which SpaceX installed and ‘sleeved’ in mid-October, Starbase’s first orbital-class tank farm is a bit like the pad’s circulatory system and needs to store, chill, and distribute all the propellant needed for a rocket launch. To support Starship and Super Heavy, both the largest individual rocket stages and the largest integrated rocket ever built, its launch site and tank farm have to be equally immense. In classic SpaceX fashion, the company has strived to keep the costs of that tank farm low and its speed of construction high, resulting in a setup that’s fairly unique as far as launch pads go.

Perhaps nothing emphasizes the scale of Starship’s first orbital-class tank farm than the process of filling it with the supercool propellant and fluids its designed to hold.

In mid-September, SpaceX began delivering cryogenic fluids to Starbase’s orbital tank farm for the first time ever. Instead of propellant, dozens of tanker trucks delivered liquid nitrogen to one or two of the farm’s tanks between mid-September and mid-October. Altogether, around 40-60 truckloads was delivered – only enough to partially fill one tank. That liquid nitrogen also appeared to be piped into two of the farm’s three liquid oxygen tanks, meaning that it may have only been used to clean and proof test them.

Combined, the farm’s seven main tanks should be able to store roughly 2400 tons (5.3M lb) of liquid methane (LCH4), 5400 tons (12M lb) of liquid oxygen (LOx), and 2600 tons (5.7M lb) of liquid nitrogen (LN2). LCH4 and LOx are Starship’s propellant, while LN2 is needed to ‘subcool’ that propellant below its boiling point, significantly increasing its density and the mass of propellant Starships can store.

In recent weeks, LN2 deliveries have picked back up at the orbital tank farm, suggesting that more tanks are being cleaned and proofed. SpaceX may have also begun filling one or both of the farm’s dedicated LN2 tanks, though it’s hard to say for sure. More importantly, around October 17th, SpaceX began filling Starship’s orbital tank farm with liquid oxygen – real propellant – for the first time. Rather than a slow and cautious process, deliveries have streamed in almost daily ever since. As of November 4th, at least 74 tanker trucks have delivered LOx to the farm in 18 days.

Based on Department of Transportation (DOT) regulations that limit the gross weight of cryogenic tanker trucks to about 37 tons (~81,000 lb), each of those trucks has likely delivered around 20 tons (~45,000 lb) of LOx to Starbase. Altogether, that amounts to around 1500 tons (3.3M lb) delivered in less than three weeks – enough to fill about 80% of one of the farm’s three LOx tanks or a quarter of its total LOx storage capacity.

Based on data from AI-based tracker Starbase Deliveries, which can only count daytime deliveries, at least 134 tankers have delivered LCH4, LOx, or LN2 to Starbase’s orbital and suborbital launch sites between October 4th and November 4th – an average of 4.3 per day. At that rate, even if every delivery went to the orbital pad, it would take SpaceX nearly four months just to fill the orbital tank farm. Put simply, the facilities and logistics required to support even a single orbital Starship launch are gargantuan.

Quelle: TESLARATI

----

Update: 14.11.2021

.

SPACEX SUCCESSFULLY TESTS ALL SIX STARSHIP ENGINES

SpaceX took another step forward in the development of its Starship system to take people and cargo to Earth orbit, the Moon, Mars and beyond. Today’s static fire test of the Starship second stage with all six engines was successful according to SpaceX founder Elon Musk.

Starship is being built and tested at SpaceX’s Starbase in Boca Chica, Texas, near Brownsville.

Starship is both the name of the entire system and of just the second stage, a combination rocket and crew/cargo compartment. Today’s test was of the second stage. The first stage, Super Heavy, also is in development at Starbase. In August SpaceX stacked the two together as a test as it moves closer to the first attempt to launch into orbit in coming months. The complete system is 395 feet (120 meters) tall with a 30-foot (9-meter) diameter.

The Starship second stage has six methane/liquid oxygen (methalox) Raptor engines. SpaceX’s five test flights to date, four of which ended in explosions, used only three.

Today’s test, with Starship Serial Number 20 (SN20), was the first time all six were fired at the same time.

Super Heavy will have 29 Raptors of its own. All of Starship, including the engines, is reusable.

Musk tweeted “Good static fire with all six engines!” SpaceX tweeted a photo of the brief event.

Musk conceived Starship as a transportation system to take millions of people to Mars, but it can go anywhere and land anywhere in the solar system.

SpaceX won a NASA contract in April to use it as the Human Landing System (HLS) for the Artemis program to return astronauts to the Moon. The contract was in abeyance for seven months while competitors protested the award, a situation resolved only last week when a court ruled in NASA’s favor. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said on Tuesday that the goal of getting people back on the Moon by 2024 is no longer possible in part because of that delay. The new goal is 2025, but that is tentative until NASA can sit down and talk with the SpaceX team about the progress they have been making in the interim using their own money.

One pacing item for the program is not technical, but regulatory. The FAA must approve the use of Starbase for orbital launches. An environmental assessment is being conducted right now. The FAA makes the pointthat “SpaceX cannot launch the Starship/Super Heavy vehicle until the FAA completes its licensing process, which includes the environmental review and other safety and financial responsibility requirements.”

Quelle: SPACEPOLICYONLINE.COM

----

Update: 19.11.2021

.

SpaceX's Musk: 1st Starship test flight to orbit in January

SpaceX is aiming to launch its futuristic, bullet-shaped Starship to orbit in January

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. -- SpaceX founder Elon Musk said Wednesday that his company will attempt to launch its futuristic, bullet-shaped Starship to orbit in January, but he’s not betting on success for that first test flight.

“There's a lot of risk associated with this first launch, so I would not say that it is likely to be successful, but we'll make a lot of progress,” he said during a virtual meeting organized by the National Academy of Sciences.

Musk said he's confident Starship — launching for the first time atop a mega booster — will successfully reach orbit sometime in 2022. After a dozen or so orbital test flights next year, SpaceX then would start launching valuable satellites and other payloads to orbit on Starships in 2023, he said.

NASA has contracted with SpaceX to use Starship for delivering astronauts to the lunar surface as early as 2025. Musk plans to use the reusable ships to eventually land people on Mars.

The shiny, stainless steel Starship and its first-stage booster — called the Super Heavy — will be the biggest rocket ever to fly, towering 394 feet (120 meters). Liftoff thrust, Musk noted, will be more than double that of NASA’s Saturn V rockets that carried astronauts to the moon a half-century ago.

The Super Heavy has yet to soar. But a full-scale Starship model in May flew to an altitude of more than 6 miles (10 kilometers) before successfully landing back at the SpaceX complex near Texas' southernmost tip.

The Starship and Super Heavy for the first orbital test flight have both been completed, according to Musk. By the end of November, the company hopes to be finished with the launch pad and tower, with testing in December. The Federal Aviation Administration should be done by the end of the year with its review, leading to a launch in January or February at the latest, Musk noted.

To date, about 90% of Starship’s development costs have been covered by SpaceX, according to Musk, with NASA covering the rest with its lunar lander contract. He did not say how much had been spent so far.

Musk plans to build multiple Starships in the near term. He envisions needing 1,000 of them to make life truly multiplanetary, his ultimate goal.

He said something natural or manmade will eventually bring about the end of civilization — a pandemic worse than COVID-19, continually decreasing birth rates, nuclear Armageddon or perhaps a direct hit by a killer comet. Moving people to Mars and elsewhere as quickly as possible, he noted, is essential "for preserving the light of consciousness.”

Quelle: abcNews