6.12.2019

Quite apart from the practicalities, there are serious ethical issues at stake, says astrophysicist Paul Davies.

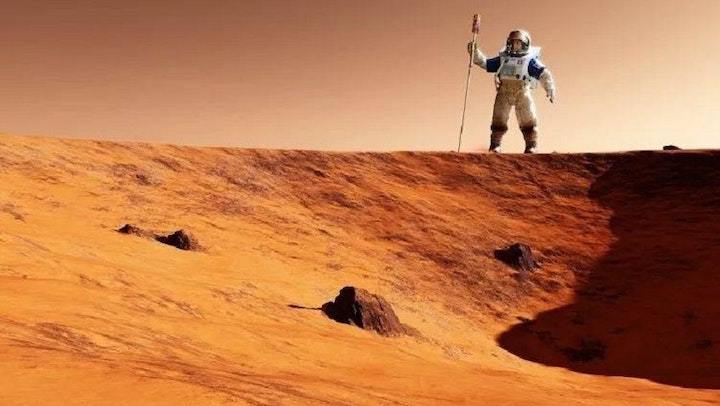

Humans may choose to undertake interstellar colonisation to keep our species, and the flame of our culture, alive.

The following is an excerpt from the article “Packing for our longest journey”, which appears in the current edition of Cosmos magazine. To subscribe, click here.

One motivation for sending humans into space is as an insurance policy against a mega-catastrophe on Earth.

Often cited is the impact of a large comet or asteroid which might destroy our civilisation or even our entire species. More likely in my view is a sudden pandemic, either naturally occurring or through the accidental release of a virulent bio-warfare pathogen.

In any case, over a period of millennia, there is no lack of potentially species-annihilating hazards. If all that stood in the way of human survival were some indigenous microbes on another world, few people would have scruples about ignoring their “rights”.

If a planet had complex plant and animal life, there should be strong ethical objections to contaminating it with terrestrial organisms. Even if the two forms of life were so biochemically different that direct infection was avoided, it may still be the case that the terrestrial invaders would plunder some vital resource and deplete the indigenous ecosystem.

Earth organisms might spread like the rabbits in Australia, and elbow the indigenous life aside, driving it to extinction.

That issue would be greatly sharpened if a target planet is found to host intelligent life. In the movie Avatar, resource-hungry humans muscle in on the planet Pandora to the extreme discomfort of its indigenous population, although in the interests of Hollywood-style justice, the pesky human invaders eventually receive their comeuppance.

There is no guarantee that future generations of humans would exercise respect for the rights of alien beings, nor can we be sure that aliens would respect ours.

Even aliens far in advance of us in technology and social development may not share our ethical values. Because we cannot begin to guess the motives and attitudes of truly alien beings, when it comes to the prospect of humans encountering an extraterrestrial civilisation, all bets are off.

It seems to be generally accepted that interstellar travel should, and could, become part of our destiny. Why?

A familiar answer is that humans have always had wanderlust, a sense of curiosity, a desire to explore the world about them and to push on to pastures new. That may be true, but people have always fought wars and oppressed minorities too; just because something is deeply ingrained in human nature does not make it a noble motivation.

Rather easier to justify is the argument that human society has produced much that is good, which it would, therefore, be good to preserve for posterity. Humans may choose to undertake interstellar colonisation to keep our species, and the flame of our culture, alive somewhere in the cosmos.

By establishing a permanent settlement on another planet, human culture could continue even if disaster struck at home. It could be countered that this argument adopts an inflated view of human significance and human worth, and that it is life, as opposed to our specific species or culture, that should be perpetuated and perhaps disseminated around the cosmos.

We could already begin sending microbes in tiny capsules out of the Solar System if we were so minded, but it is hard to imagine much enthusiasm for the project. Seeding a barren galaxy with DNA may one day fire people’s imagination (assuming the galaxy is not already teeming with life), but today the appeal of interstellar travel is deeply rooted in ideals of human adventure and advancement.

When Neil Armstrong took that first small step on the Moon, it was widely hailed as the initial step on a stairway to the stars. Half a century on, with humans seemingly stuck in low-Earth orbit, the prospects for interplanetary, let alone interstellar, travel look bleak.

These microbiology problems compound what is already a formidable challenge in spacecraft design, propulsion systems and medical technology. Yet if humans wish to secure a long-term future in an uncaring and occasionally dangerous cosmos, some form of cosmic diaspora needs to be part of our long-range plan.

Quelle: COSMOS