.

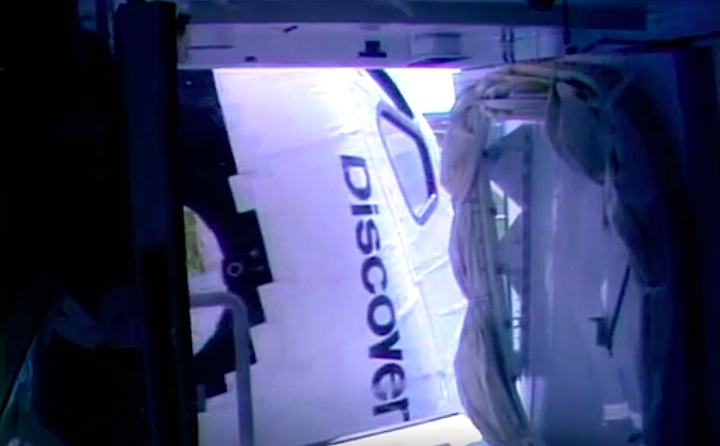

Space Shuttle: Discovery

Launch Pad: 39B

Launch Weight: 254,606 pounds

Launched: Sept. 29, 1988, 11:37:00 a.m. EDT

Landing Site: Edwards Air Force Base, Calif.

Landing: October 3, 1988, 9:37:11 a.m. PDT

Landing Weight: 194,184 pounds

Runway: 17

Rollout Distance: 7,451 feet

Rollout Time: 46 seconds

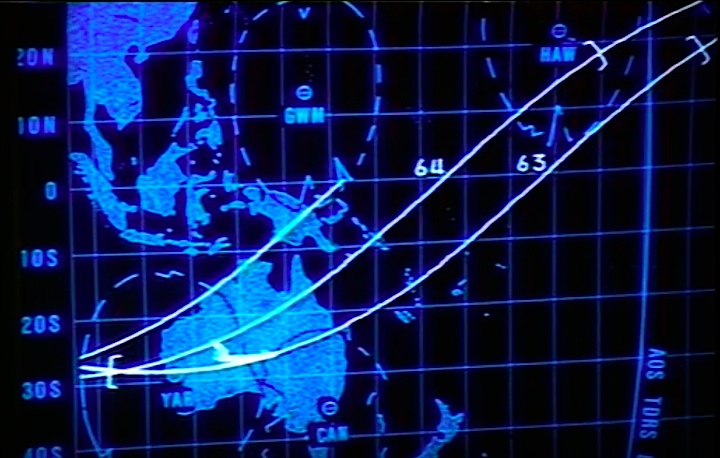

Revolution: 64

Mission Duration: 4 days, 1 hour, 0 minutes, 11 seconds

Returned to KSC: Oct. 8, 1988

Orbit Altitude: 203 nautical miles

Orbit Inclination: 28.5 degrees

Miles Traveled: 1.7 million

Crew Members

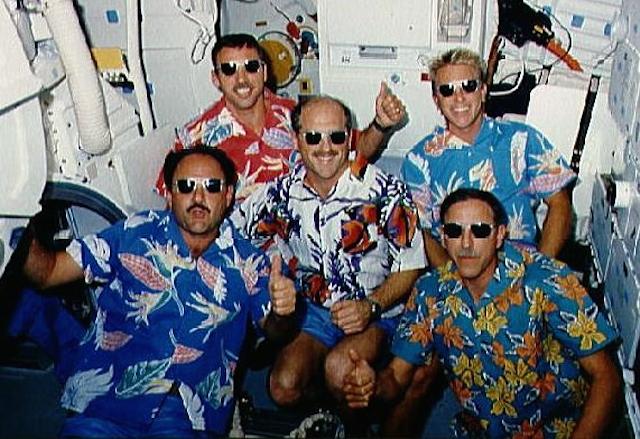

Image above: STS-26 Crew photo with Commander Frederick H. Hauck, Pilot Richard O. Covey, Mission Specialists John M. Lounge, George D. Nelson and David C. Hilmers. Image Credit: NASA

Launch Highlights

The launch was delayed 1 hour, 38 minutes to replace fuses in the cooling system of two of the crew's flight pressure suits, and due to lighter than expected upper atmospheric winds. The suit repairs were successful and the countdown continued after a waiver of wind condition constraint was issued.

The launch was delayed 1 hour, 38 minutes to replace fuses in the cooling system of two of the crew's flight pressure suits, and due to lighter than expected upper atmospheric winds. The suit repairs were successful and the countdown continued after a waiver of wind condition constraint was issued.Mission Highlights

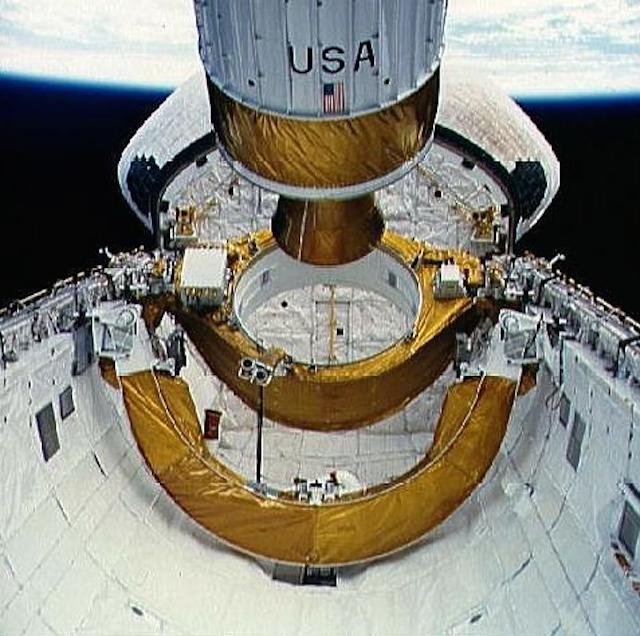

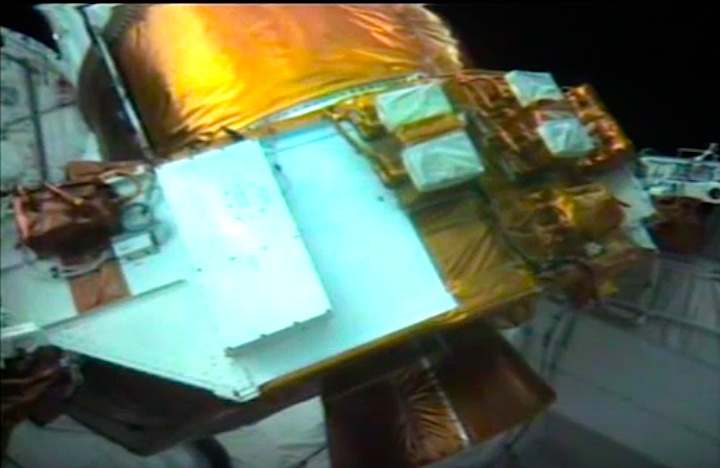

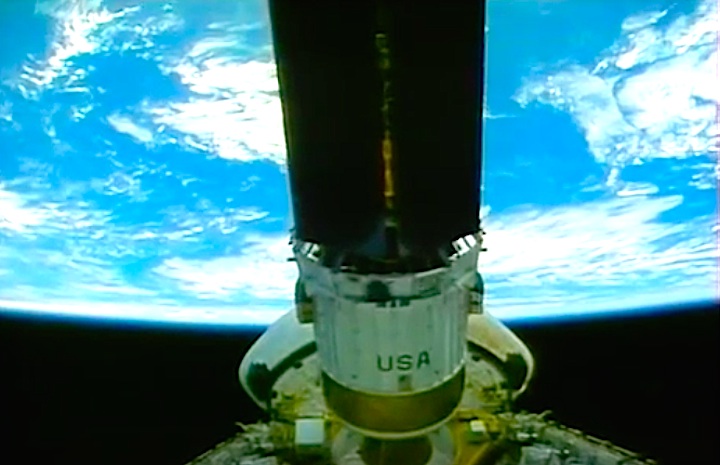

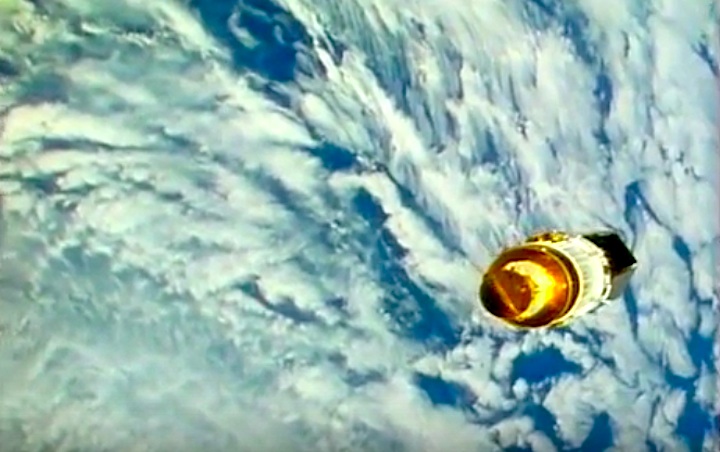

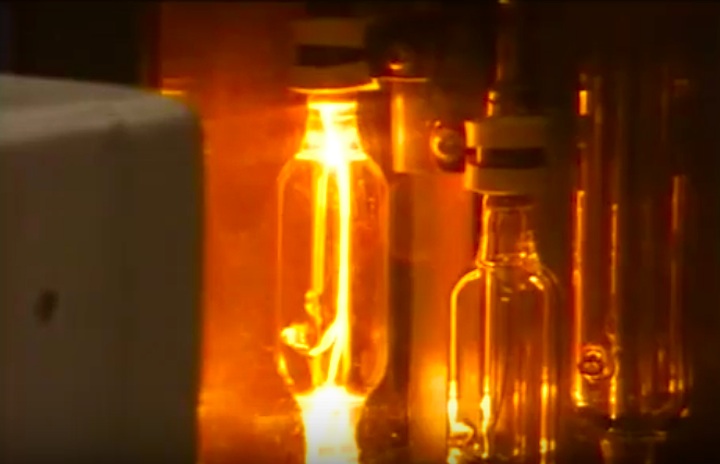

The primary payload, NASA Tracking and Data Relay Satellite-3 (TDRS-3) attached to an Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), became the second TDRS deployed. After deployment, IUS propelled the satellite to a geosynchronous orbit. Secondary payloads: Physical Vapor Transport of Organic Solids (PVTOS); Protein Crystal Growth (PCG); Infrared Communications Flight Experiment (IRCFE); Aggregation of Red Blood Cells (ARC); Isoelectric Focusing Experiment (IFE); Mesoscale Lightning Experiment (MLE); Phase Partitioning Experiment (PPE); Earth-Limb Radiance Experiment (ELRAD); Automated Directional Solidification Furnace (ADSF) and two Shuttle Student Involvement Program (SSIP) experiments. Orbiter Experiments Autonomous Supporting Instrumentation System-I (OASIS-I) recorded variety of environmental measurements during various inflight phases of orbiter.

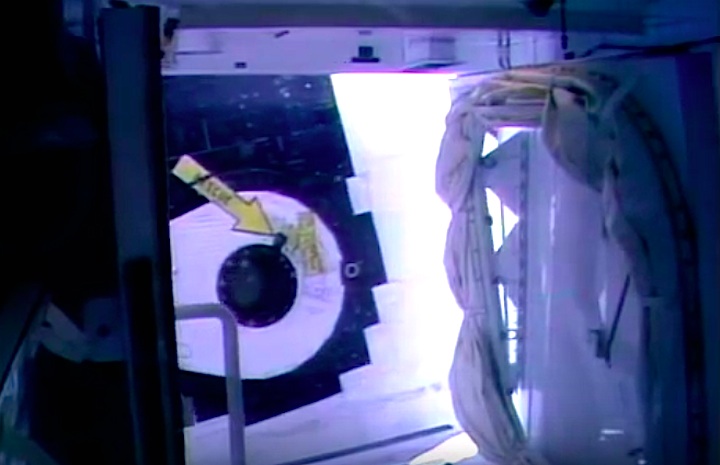

Ku-band antenna in the payload bay was deployed; however, the dish antenna command and actual telemetry did not correspond. Also, the orbiter cabin Flash Evaporator System iced up, raising crew cabin temperature to the mid-80s.

Return to Flight: Richard H. Truly

and the Recovery from the

Challenger Accident1

by John A. Logsdon

Seventy-three seconds after its 11:37 a.m. liftoff on September 29, 1988, those watching the launch of the Space Shuttle Discovery and its five-man crew breathed a collective sigh of relief. Discovery had passed the point in its mission at which, on January 28, 1986, thirty-two months earlier, Challenger had exploded, killing its seven-person crew and bringing the U.S. civilian space program to an abrupt halt.2 After almost three years without a launch of the Space Shuttle,3 the United States had returned to flight.

Presiding over the return-to-flight effort for all but one of those thirty-two months was Rear Admiral Richard H. Truly, United States Navy. Truly was named Associate Administrator for Space Flight of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on February 20, 1986. In that position, he was responsible not only for overseeing the process of returning the Space Shuttle to flight, but also for broader policy issues such as whether the Challenger would be replaced by a new orbiter, what role the shuttle would play in launching future commercial and national security payloads, and what mixture of expendable and shuttle launches NASA would use to launch its own missions. He served as the link between the many entities external to NASA —the White House, Congress, external advisory panels, the aerospace industry, the media, and the general public— with conflicting interests in the shuttle's return to flight. In addition, he had the tasks of restructuring the way NASA managed the Space Shuttle program and restoring the badly shaken morale of the NASA-industry shuttle team.

The citation on the 1988 Collier Trophy presented to Admiral Richard H. Truly read: "for outstanding leadership in the direction of the recovery of the nation's manned space program." This essay recounts the managerial and technological challenges of the retum-to-flight effort, with particular attention to Richard Truly's role in it. However, as Truly himself

1. This essay's findings and conclusions are the responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of NASA or the George Washington University. The author wishes to acknowledge with gratitude the dogged research assistance of Nathan Rich; without his efforts, the task would have been much more difficult.

2. This essay is not an account of the Challenger accident, but rather the process of recovering from that mishap. For such an account, see Malcolm McConnell, Challenger: A Major Malfunction (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1987).

3. The formal name for the combined Shuttle orbiter, Space Shuttle main engines, external tank, and solid rocket boosters, plus any additional Spacelab equipment mounted in the orbiter's payload bay, is the Space Transportation System(STS). In this essay, the terms Shuttle or Space Shuttle are often used as an alternate way of identifying the STS.

345

346 RETURN TO FLIGHT

|

| It's thumbs up for the shuttle as the STS-26 Discovery crew celebrate their return to Earth with Vice President George Bush. The orbiter completed a successful four-day mission with a perfect touch down on October 3, 1988, on Rogers Dry Lake Runway 17. In this picture, from left to right, are: Mission Specialist David C. Hilmers, Commander Frederick H. (Rick) Hauck, Vice President George Bush, Pilot Richard O. Covey, and Mission Specialists George D. Nelson and John M. Lounge. (NASA photo no. 88-H-497). |

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 347

recognized, the recovery program was a comprehensive team effort;4 as the first post-Challenger flight approached, he sent a memorandum to the "NASA Space Shuttle Team," saying:

As I reflect over the challenges presented to us, and our responses to them, my overriding emotion is one of pride in association. You —the men and women who compose and support this unique organization— should take great pride in having renewed the foundation for a stronger, safer American space program. I am proud to have been a part of this effort; I am proud to have witnessed your extraordinary accomplishments.5

Immediate Post-Accident Events6

When Truly was named NASA Associate Administrator for Space Flight, he told the press that in the three weeks since the Challenger accident he had not "had one moment" to review information about the mishap.7 Whether he realized it or not, Truly was entering a very chaotic situation. At the time of the accident, NASA Administrator James Beggs was on a leave of absence to deal with a Federal indictment unrelated to his NASA duties. (Beggs was later completely exonerated of any wrong doing and even received a letter of apology from the Attorney General for being mistakenly indicted.) Acting as Administrator was NASA Deputy Administrator William Graham, a physicist with close ties to conservative White House staff members but no experience in civilian space matters prior to being proposed for the NASA job. A few weeks earlier, Graham had been named Deputy Administrator, a White House political appointment, over the objections of Beggs and other senior staff at NASA; in his short time on the job he had remained largely isolated from career NASA employees. When Challenger exploded, NASA was thus bereft of experienced and trusted leadership.

Graham was in Washington when the accident occurred. Later in the day, be flew to the Kennedy Space Center with Vice President George Bush and Senators John Glenn and Jake Garn. The latter three flew back to Washington after consoling the families of Challenger crew members and meeting with the Shuttle launch team. Graham stayed behind; in a series of phone calls to the White House during the night, a decision was made to have the President appoint an external review commission to oversee the accident investigation. Although Graham had been briefed by his NASA staff on how the investigation after the 1967 Apollo 1 fire had been handled, he apparently did not argue that the NASA Mishap Investigation Board, set up immediately after the accident, should continue to lead the inquiry.

This naming of an external review panel was in marked contrast to what had happened nineteen years earlier, on January 27, 1967. When he learned that a fire during a launch pad test had killed the three Apollo 1 astronauts, NASA Administrator James Webb immediately notified President Lyndon Johnson, and told him that NASA was best qualified to conduct the accident investigation. Webb later that evening told his associates that

4. Of those who worked closely with him in the return-to-flight effort, Truly singles out for particular praise Arnold Aldrich, Richard Kohrs, and Gerald Smith. Each of them, he notes "deserve an arm or a leg of the Collier Trophy." Personal communication to the author, August 14, 1995.

5. NASA, Memorandum from M/Associate Administrator for Space Flight to NASA's Space Shuttle Team, "Return to Flight," June 10, 1988.

6. Unless otherwise cited, this narrative of the return-to-flight effort is based on accounts in the leading trade journal Aviation Week & Space Technology (hereafter AW&ST), New York Times, and the Washington Post. All three gave detailed coverage to the effort.

7. New York Times, February 21, 1986, p. A12.

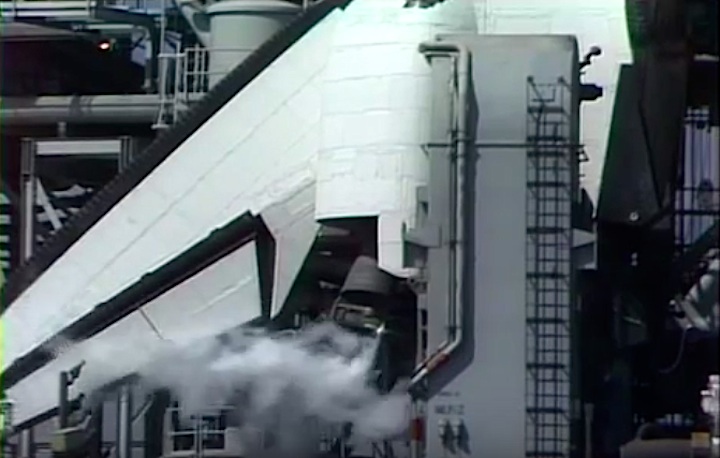

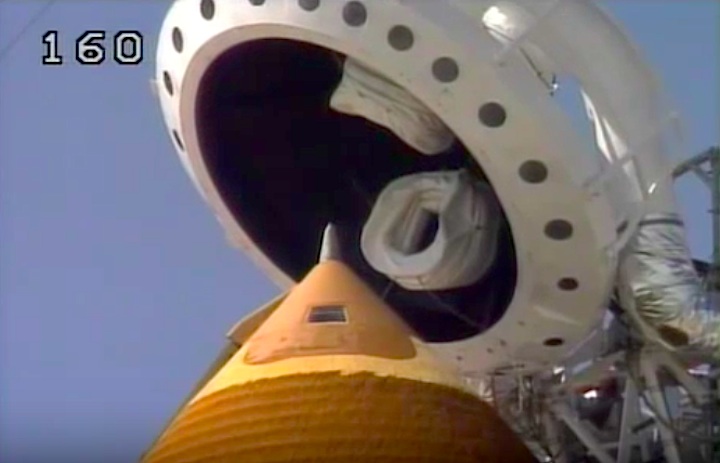

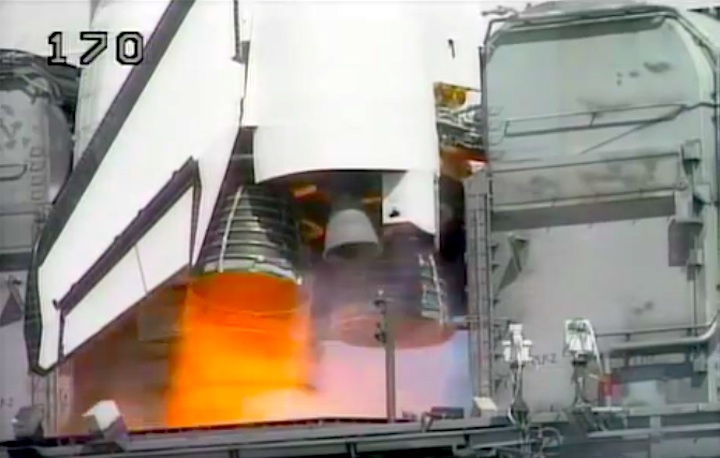

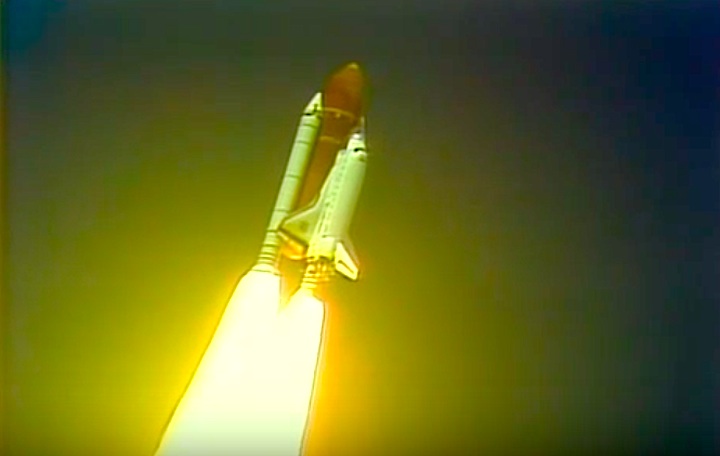

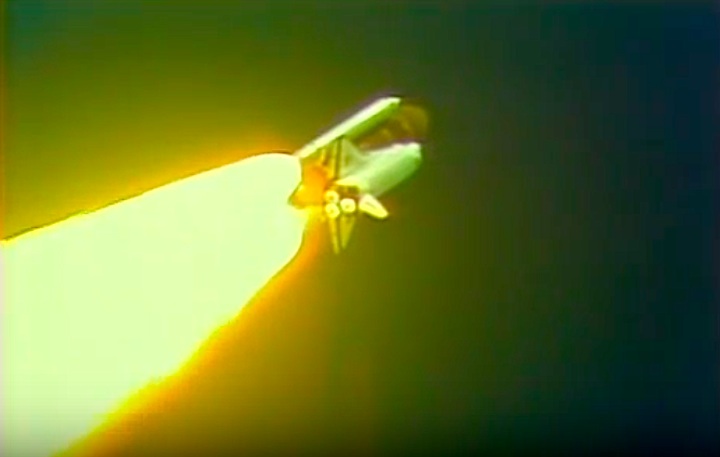

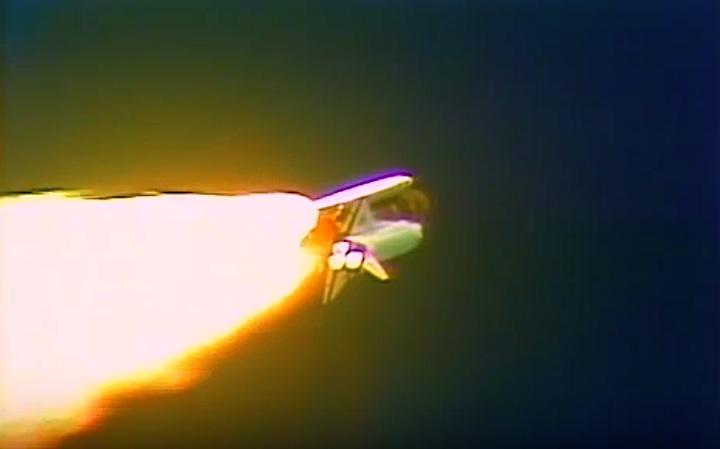

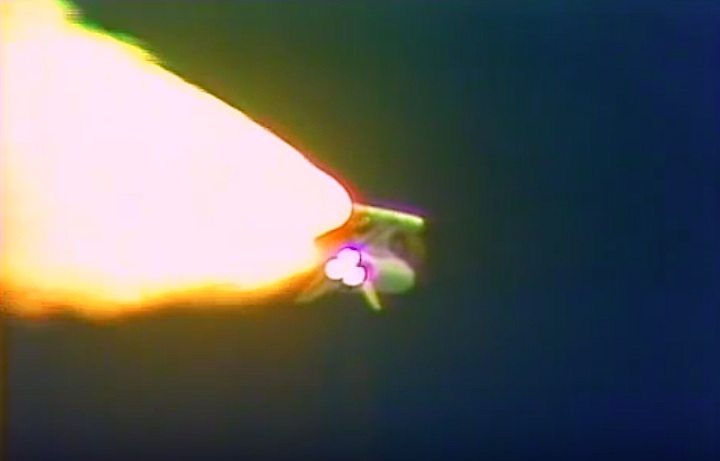

EC88-0197-1

The Space Shuttle Discovery takes off from Launch Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center, FL, as Mission STS-26 on 29 September 1988,11:37:00 a.m. EDT. The 26th shuttle mission lasted four days, one hour, zero minutes, and 11 seconds. Discovery landed 3 October 1988, 9:37:11 a.m. PDT, on Runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base, CA. Its primary payload, NASA Tracking and Data Relay Satellite-3 (TDRS-3) attached to an Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), became the second TDRS deployed. After deployment, IUS propelled the satellite to a geosynchronous orbit.

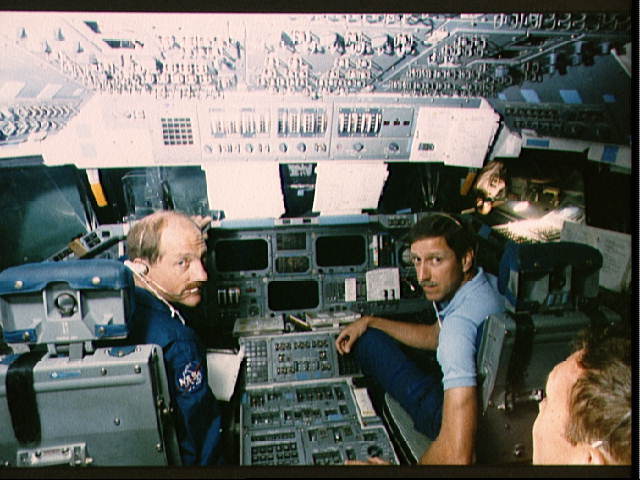

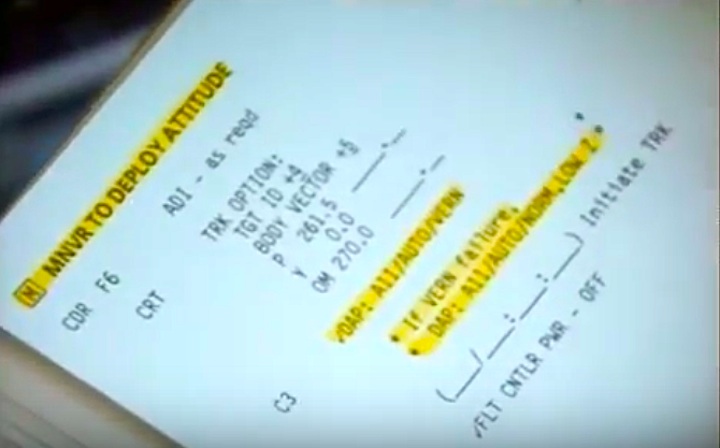

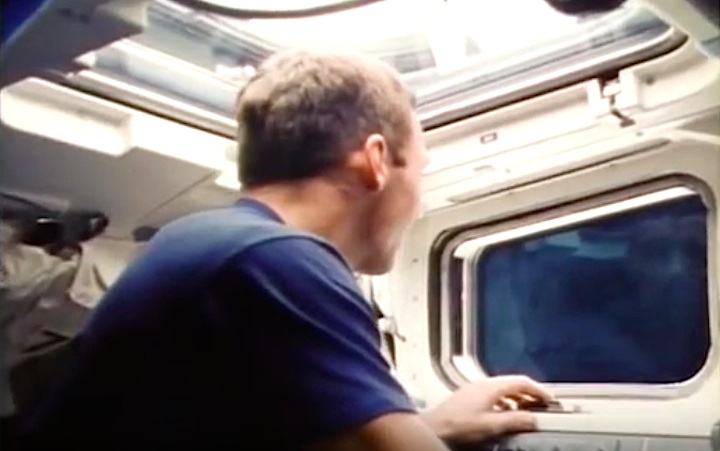

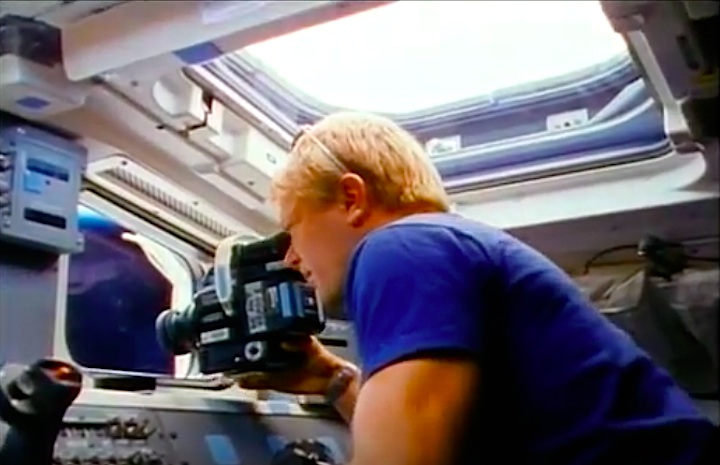

STS-26 crew trains in JSC fixed-based (FB) shuttle mission simulator (SMS)

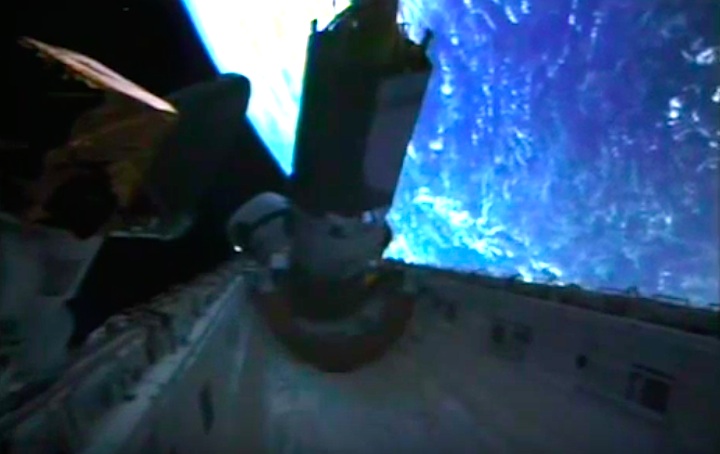

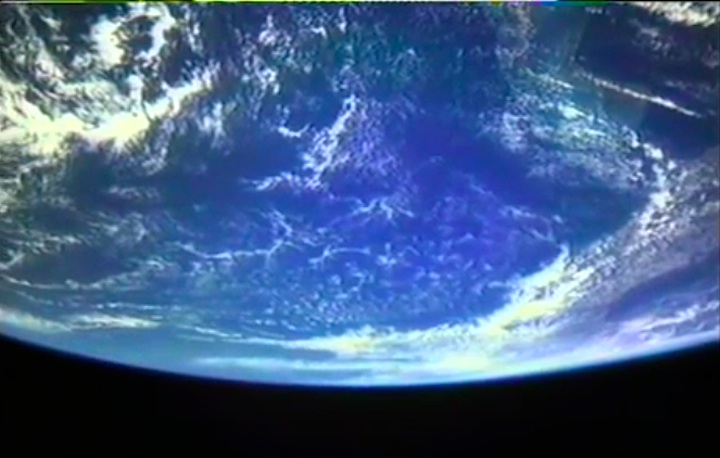

Shuttle Discovery ascends to orbit beginning mission STS-26

STS-26

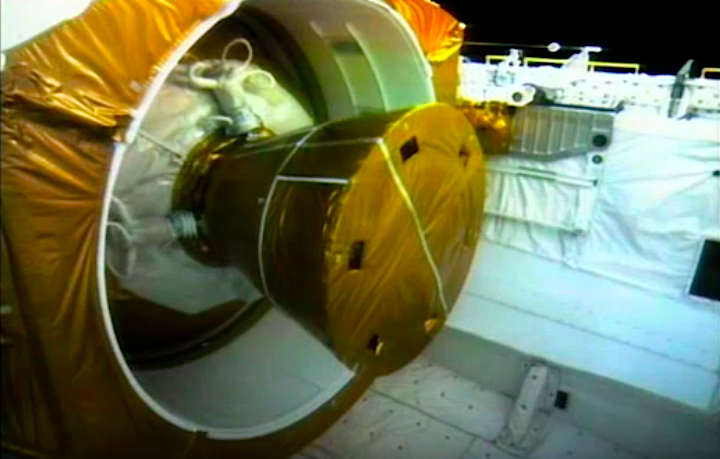

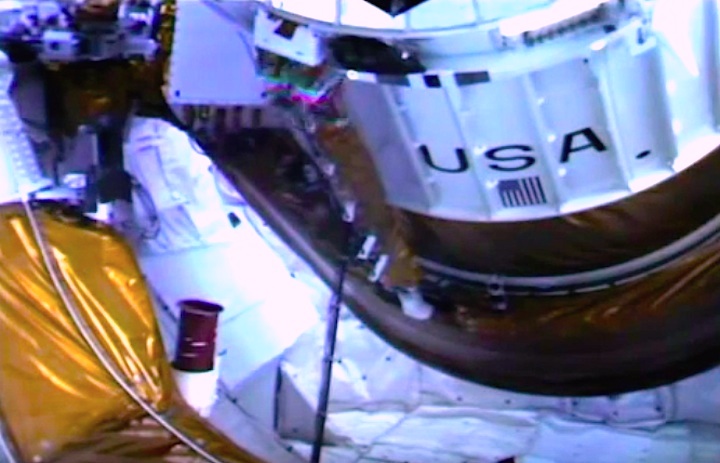

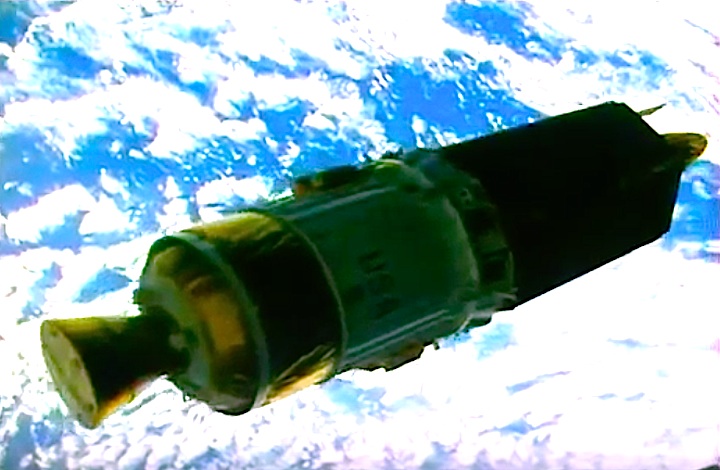

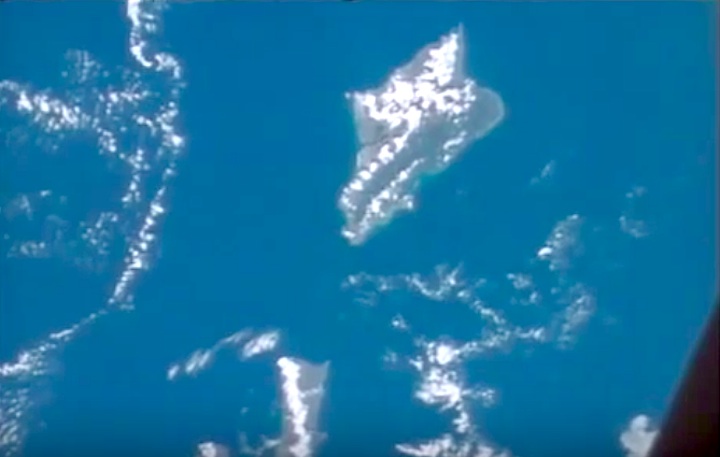

STS-26 Discovery, Orbiter Vehicle (OV) 103, IUS / TDRS-C deployment

Credit: NASA

---

Frams von STS-26 Discovery Mission NASA-Video:

Quelle: NASA