After protests and a judge's ruling brought the colossal Thirty Meter Telescope project to a halt, a state panel has cleared the way for its construction atop Mauna Kea to proceed.

On September 29th, after five months of public hearings that involved 71 witness testimonies and a review of more than 800 submitted documents, the Board of Land and Natural Resources for the state of Hawai'i announced its decision to allow the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope atop Mauna Kea to resume.

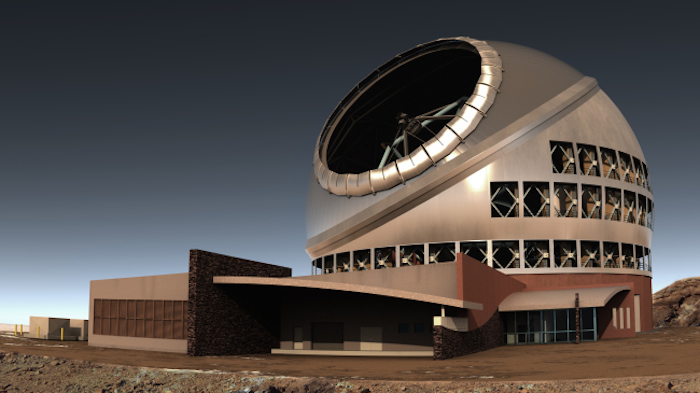

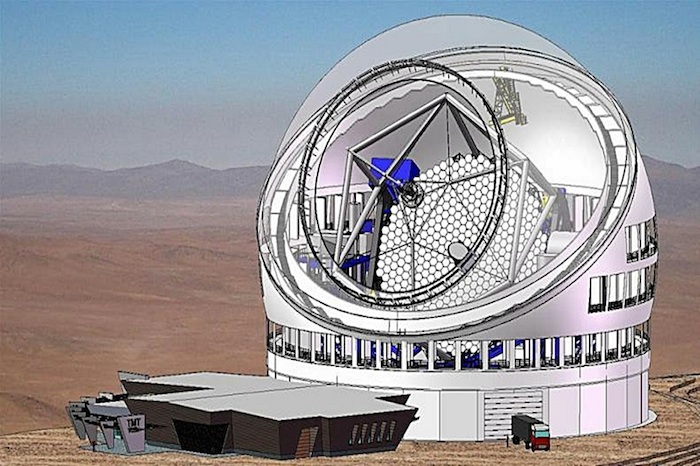

This artist's conception shows an aerial view of the Thirty Meter Telescope on top of Mauna Kea.

TMT

An earlier BLNR ruling had also approved the $1.4 billion project, but it was a controversial decision and construction ground to a halt in 2015 after a string of protests blocked access to the mountain's summit. Then last December, Third Circuit Court judge Greg Nakamura ruled that TMT’s sublease agreement with the University of Hawai'i at Hilo for the site was invalid because the BLNR should have held a separate hearing regarding the lease.

Yesterday's BNLR announcement, made after a 5-to-2 vote by its members, means that construction of the TMT can proceed. However, that's unlikely because opponents plan to appeal the decision to the Hawai'i Supreme Court. Pending that appeal, no protests on the mountain have materialized yet. However, the Hawai'i Unity & Liberation Institute declared, "As daunting of a task it might be to stop construction of the TMT, we have once again been left with no choice but to resist and take matters back into our own hands."

Arrested protesters chant before police remove them from the summit of Mauna Kea on April 2, 2015.

Occupy Hawaii

Indigenous Hawaiians consider Mauna Kea sacred, and it has long been the site of religious ceremonies and burials. Its slopes are dotted with shrines, offering altars, and hidden burial grounds. Yet the summit, 13,802 feet (4,207 meters) high, has long been prized by astronomers for its pristine, nearly cloud-free access to the night sky.

Thanks to a series of agreements, stretching back to 1968, the state has allowed the University of Hawai'i to develop and manage observatories on a 65-acre "science reserve" at the summit. The latest version of the management plan, from 2009, specifies terms for the 13 facilities now in place.

But TMT is not just another telescope. Its dome will be 218 feet (66 m) across and 180 feet (55 m) high. Ordinarily, that would be easily visible from much of the Big Island. However, explains Tom Geballe (Gemini Observatory), "The TMT site is on a lava plain several hundred feet of elevation below the summit and will be visible from very few locations on the island. It will not even be visible from the summit itself (unlike many of the other telescopes)."

Aside from its sheer size, opponents argued that construction would disturb sacred sites and that, once completed, its day-to-day operation might contaminate the summit.

The Ruling's Caveats

In allowing the construction of TMT to move forward, the state board's 345-page report concluded that the TMT project satisfied eight key criteria covering appropriate land use, conservation, and environmental concerns. As the ruling pointedly notes in its preface, "The TMT will not pollute groundwater, will not damage any historic sites, will not harm rare plants or animals, will not release toxic materials, and will not otherwise harm the environment. It will not significantly change the appearance of the summit of Mauna Kea from populated areas on Hawai‘i Island."

Speaking to reporters during the announcement, BNLR chairperson Suzanne Case addressed opponents' contention that the TMT would infringe on religious rights. "Under the federal and state constitutions," she stated, "a group's religious beliefs cannot be given veto power over the use of public land."

However, after carefully weighing the many objections raised during the public hearings, the board also imposed 43 special conditions. Among them:

- Three existing telescopes will be decommissioned and removed from the summit, with no other telescopes replacing them. Although the report doesn't say so specifically, plans are already well under way to remove the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory and a domed 0.7-m teaching telescope called Hoku Kea. The James Clerk Maxwell Telescope is a rumored third candidate.

- Two more existing facilities, including the Very Long Baseline Array antenna, must be removed by the end of 2033.

- All project employees must receive mandatory cultural and natural-resources training.

- TMT must adopt a "Zero Waste Management" policy, trucking all waste products off the summit.

- The project must contribute $1 million annually, in addition to the $2½ million it has provided each year since 2014, to community projects on the Big Island.

Some of these requirements, especially the removal of existing telescopes, closely follow a 10-point "Path Forward" request that Governor David Ige made to the University of Hawai'i in May 2015.

A statement by the University of Hawai'i about the BNLR decision notes, in part, "The university first applied for this permit seven years ago, and we believe this decision and the underlying vote represent a fitting and fair reflection of an issue that has divided many in the community who care deeply about Maunakea."

Meanwhile, the possibility remains that TMT will not be built in Hawai'i at all. Project officials had looked at other potential sites, both north and south of the equator, and had homed in on La Palma in the Canary Islands as a suitable location. However, for now Mauna Kea remains the most desirable site. That could change pending opponent's challenges before the state's Supreme Court.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope

---

Update: 30.01.2018

.

The era of extremely large telescopes

Ground-based observatories rarely attract the attention, and controversy, of large space missions. The Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) has been an exception to that.

TMT has been the subject of political debate, protests, and lawsuits in recent years, based on opposition from some native Hawaiians to plans to build the observatory atop Maunakea on the Big Island of Hawaii. A Hawaiian court ruled a state agency had improperly awarded a construction permit for the telescope, forcing the organization developing the TMT, the TMT International Observatory (TIO) LLC, to go through a new “contested case” process for a permit.

At the same time, the organization was developing a backup plan. In October 2016 it announced the selection of a backup site, Observtorio del Roque de los Muchachos (ORM) on La Palma in the Canary Islands. Planning for developing TMT there has been going on in parallel with the ongoing legal process in Hawaii. At a meeting last January of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Texas, telescope officials suggested a decision on whether the build TMT in Hawaii or La Palma would be made by that fall (see “Decision time for the Thirty Meter Telescope,” The Space Review, January 9, 2017).

A year later, that decision is still forthcoming, but project officials said they plan to make a choice soon. “Maunakea certainly remains our preferred site for TMT. ORM is an excellent alternative should Maunakea prove impractical,” said Tom Soifer, a Caltech physics professor and member of the board of the TMT International Observatory, during a town hall meeting about the telescope at the AAS meeting early this month in suburban Washington. “Our board, the TIO board, will be making a decision about the site in the spring of 2018, with a plan to initiate construction as soon as possible thereafter.”

The two sites will be in different stages of readiness if the TIO board sticks to that schedule. The TMT won a victory in Hawaii in September when the Hawaii Board of Land and Natural Resources approved a new construction permit for the telescope atop Maunakea. But, Soifer noted, opponents of the telescope appealed the decision to the Hawaii Supreme Court, even as the state appealed the ruling the required the contested case hearing in the first place. “You’d be amazed at all of the things lawyers can find to do,” he said.

On La Palma, the process has been much smoother. Construction planning documents are nearly complete for the ORM site, Soifer said, and an environmental impact had been submitted to the local government. With no evidence of significant opposition to the telescope, he said he expected the government to issue a permit for building TMT there by February or March.

Maunakea, though, remains the preferred site for several scientific reasons. The lower latitude of Maunakea will allow the telescope to see more of the southern sky than at ORM. The lower altitude of ORM—more than 1,500 meters below Maunakea—means more water vapor in the atmosphere, affecting infrared observations. “For wavelengths beyond about 2.5 microns, observations for longer wavelengths are compromised” there versus Maunakea, Soifer said.

The legal dispute in Hawaii, though, won’t be completed by the planned April deadline for a decision. “The appeals have been filed, but the court has not made any indication of what it wants to do with those appeals,” Soifer said after the town hall meeting. “The best case would be late spring or early summer of 2018.”

Even if a decision leads to work starting this year, Soifer said it would not be until the late 2020s before the TMT is ready to being observations. “If we start construction during 2018, we should be seeing first light about a decade later,” he said.

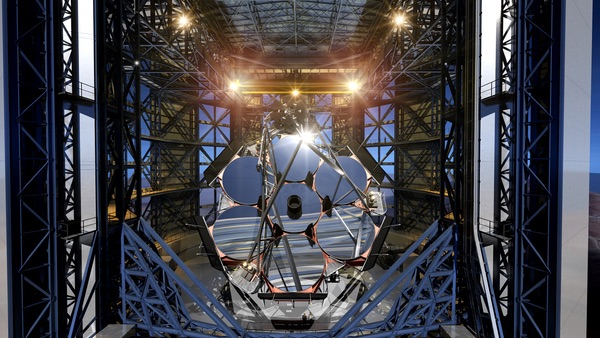

The Giant Magellan Telescope will feature seven mirrors, each more tha eight meters in diameter. (credit: GMT Organization)

|

The other large telescopes

TMT is not the only so-called “extremely large telescope” under development. Two others are also in early phases of development in the Southern Hemisphere that have largely escape the controversy surrounding the TMT.

| “If you couldn’t do more than one mirror at a time, it would be hopeless,” McCarthy said. |

One is the European Southern Observatory’s Extremely Large Telescope in Chile. Like the TMT, it will consist of hundreds of small mirror segments—798, to be exact—that will be combined to form a single mirror with a diameter of 39 meters. The observatory announced this month that first six of those segments have been cast at a German factory, keeping the project on track for a first light in 2024.

The other is the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), which will also be built in Chile. Unlike the other two projects, it plans to use seven large mirrors, each 8.4 meters in diameter, creating an effective aperture of 24.5 meters. The project started casting the fifth of those seven mirrors in November.

“We’re now at the stage that we’re really into construction. It’s becoming a real thing now. We’re building a lot of optics. We’re under contract to build the telescope and we’re just about to get under contract to starting digging holes on top of the mountain” for the observatory, said Pat McCarthy, vice president for operations and external relations at the Giant Magellan Telescope Organization, in an interview during the AAS conference.

By 2021, he said, “things will really start to show up on the mountain” as the observatory building nears completion. By 2024 and 2025, he said, the mirrors will be installed and operations will begin.

Building the mirrors, he said, is the long pole in the project schedule, taking about five years to go from a pile of glass to a completed, polished mirror. “If you couldn’t do more than one mirror at a time, it would be hopeless,” he said. “We can be working on four to five at a time.”

Those mirrors posed a number of technical challenges. That size, he said, is near the maximum feasible size for a monolithic mirror, given factors ranging from the time it takes for the glass to cool after casting to its weight and risk of breakage. While other telescopes, like the TMT and the Extremely Large Telescope, are using large numbers of small segments to create a large mirror, “we’ve gone the other approach, deciding it’s best to have as much contiguous surface area as you can, so we make the biggest possible segments.”

However, not all the segments are alike: the seven segments have to be aligned so that most of them have off-axis shapes. “You have to polish eight-meter mirrors that have off-axis figures, and that’s turned out to be hard,” McCarthy said. “That was the biggest technical challenge: how do you make these complex, off-axis mirrors.” The project has figured out how to do so, he said, and is now looking at how to speed up the production process.

Another challenge is the telescope enclosure, which eschews the standard spherical dome shape for a cylindrical structure that is the equivalent of a building 20 to 22 stories tall. That structure needs to move around and be open as well. The project, he said, brought in Boeing to leverage its expertise in computational fluid dynamics and wind tunnel testing to model the structure’s aerodynamics.

“While we are not flying, we are experiencing some of the aerodynamics effects, the turbulence effects, which they deal with,” he said of Boeing. “They’ve been a very good partner helping us model the structure and optimize some of the architectural choices before we finalize those in concrete.”

There are also financial challenges. The GMT has an estimated cost of $1 billion, and when the project started its various partners provided more than $500 million to begin development, with some more raised since. “That’s enough to get us through all the remaining design work, keep the mirror production going, to start the construction,” he said.

| “The global community of people working on these big telescopes are all interested in pretty much the same big science questions,” he said. “Where did we come from? What’s the universe made of? How is it evolving? Where are we going?” |

However, the project still needs to raise an undisclosed amount to fully pay for the telescope. “We’ve got a fundraising operation that is up and running. We’re making good progress with meeting with prospective donors,” he said. “I think we’re in good shape on that. It’s just going to be an uphill climb.”

One advantage McCarthy said that the GMT will have over the other two large telescopes is that its “fast” optical design and wider field of view. “Because of this compact optical nature, it’s easy for us to build conventional instruments: conventional spectrographs, conventional cameras,” he said.

One of the initial instruments available at the GMT will be high-precision, high-resolution spectrometer, which the other two observatories will not have when they open since the optical designs of those telescopes make such instruments more difficult to design. “TMT and the European ELT will have those eventually, but they’re much harder to build,” he said. “It probably will take them a little longer.”

Ultimately, though, all three extremely large telescopes, whenever and wherever they’re completed, will be doing similar science. “The global community of people working on these big telescopes are all interested in pretty much the same big science questions,” he said. “Where did we come from? What’s the universe made of? How is it evolving? Where are we going? These are the basics that we all are dealing with, but the structure of how you go about it differs from one project to another.”

Quelle: The Space Review

---

Update: 14.04.2018

.

Hawaii board delays decision on location for giant telescope

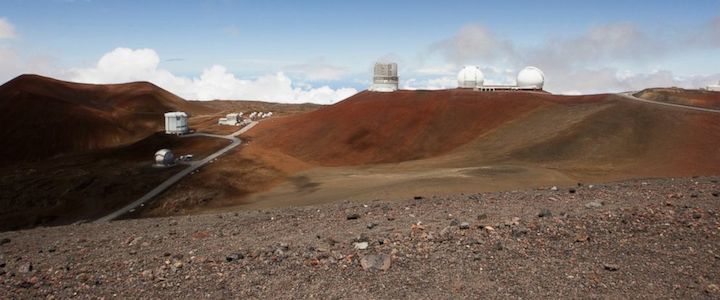

FILE - In this Aug. 31, 2015 file photo, telescopes are shown on Mauna Kea, Hawaii's tallest mountain and the proposed construction site for a new $1.4 billion telescope, near Hilo, Hawaii. On Friday, April 13, 2018, officials with the Thirty Meter Telescope International Observatory have delayed a decision whether to continue efforts to construct it at its preferred site in Hawaii or at an alternate site in Spain's Canary Islands. (AP Photo/Caleb Jones, File)

-

A key decision on whether to place a $1.4 billion telescope in Hawaii to further astronomy research has been delayed, leaving open the possibility the project may be moved to Spain, a panel said Friday.

The board of governors for the project dubbed the Thirty Meter Telescope International Observatory still wants to build the telescope on its preferred site of Mauna Kea, a mountain in Hawaii.

But an alternative location in Spain's Canary Islands remains under consideration, the board said in a statement after meeting this week to discuss legal and regulatory challenges to the Hawaii telescope plan that could last years.

"We continue to assess the ongoing situation as we work toward a decision," said Ed Stone, the executive director of the observatory.

He said no decision can be made on where to put the telescope "until we have a place to go, and we don't decide when we have a place to go — that's decided by the courts and agencies."

The 30-meter (98 feet) diameter telescope would be placed on one side of Mauna Kea and is far more advanced than the world's largest current telescopes that measure 10 meters (32 feet) in diameter. The new telescope could potentially allow scientists to make groundbreaking discoveries about black holes, exoplanets, celestial bodies, and even detect indications of life on other planets.

Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano and Hawaii's tallest mountain, was selected in July 2009 as the target location for the telescope after a five-year search.

Scientists called it the best site in the world for astronomy, given a stable, dry, and cold, climate, which allows for sharp images. The atmosphere over the mountain also provides favorable conditions for astronomical measurements, according to the TMT website.

The island of La Palma in the Canary Islands, which already has an astronomical observatory, is considered a viable alternative. But scientists have said the telescope's design would have to be altered for more adaptive optics given the mountain site's lower altitude and different climate. That means it would take scientists more time to achieve the same discoveries they could make at Mauna Kea, Stone said.

The Hawaii site has been subject to years of public debate and legal challenges. Researchers say it will help usher in scientific and economic developments, while opponents maintain it will hurt the environment and desecrate land considered sacred by some Native Hawaiians. Mauna Kea already houses a number of high-powered telescopes at its summit.

"Thirty years of astronomy development has resulted in adverse significant impact to the natural and cultural resources of Mauna Kea," said Kealoha Pisciotta, president of Mauna Kea Anaina Hou, an indigenous, Native Hawaiian group that works on environmental issues. "Trying to build more would have added to the cumulative impact."

On Thursday, the Hawaii Senate approved a bill to ban new construction atop Mauna Kea, and included a series of audits and other requirements before the ban could be lifted. But House leaders said they don't have plans to advance the bill. Democratic House Speaker Scott Saiki told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that the "bill is dead on arrival in the House."

There are also two appeals before the Hawaii Supreme Court. One challenges the sublease and land use permit issued by the Hawaii Board of Land and Natural Resources. The other has been brought by a Native Hawaiian man who says use of the land interferes with his right to exercise cultural practices and is thus entitled to a case hearing.

The telescope project is a collaboration among universities in the U.S. and California, including the University of Hawaii and national science and research institutes of Japan, China, and India.

"It's a privilege to practice astronomy on Mauna Kea and we're not satisfied with where we're at right now," Dan Meisenzahl, a spokesperson for the University of Hawaii, said in a statement. "We will continue to push ourselves to improve our stewardship of the mountain."

Quelle: abcNews

+++

TMT BOARD DEFERS DECISION ON THIRTY METER TELESCOPE SITE

The TMT International Observatory (TIO) Board of Governors at its meeting this week deferred a decision on whether to continue towards building the Thirty Meter Telescope in Hawaii, or to consider the alternative in the Canary Islands.

A decision will be made on the planned location of the Thirty Meter Telescope as further progress is made in the legal and regulatory processes at both proposed sites.

“We continue to assess the ongoing situation as we work toward a decision,” said Ed Stone, Executive Director of the TMT International Observatory (TIO).

In Hawaii, there are two appeals before the Hawaii Supreme Court. The Hawaii state land board, also known as the Hawaii Board of Land and Natural Resources, voted last fall to reissue a Conservation District Use Permit that would allow construction of the telescope on Maunakea. The matter has been appealed before the Hawaii Supreme Court and legal briefs have been filed in that case.

Oral arguments for the other court appeal, involving a consent to sublease, were held before the Hawaii Supreme Court in March.

“TMT is grateful that the legal process is moving forward in Hawaii and we remain hopeful of court decisions that will allow us to resume construction on Maunakea,” said TIO Board Chair Henry Yang. “We remain respectful of and will continue to follow the legal and regulatory processes.”

The environmental and permitting process required to build in the Canary Islands, at the La Palma site, is continuing. The environmental impact assessment for the project has been submitted to the relevant authorities and, once the document is accepted, permits for construction and other clearances will be applied for.

“While Maunakea remains our preferred choice,” Stone said, “we continue to work closely with planning officials at our alternative site in the Canary Islands.”

Significant fabrication of the Thirty Meter Telescope’s infrastructure and components continues off-site by the participating partners in the project.

“With work progressing around the partnership, we are ready to initiate on-site construction,” Stone added.

Quelle: TMT International Observatory