25.09.2022

James Webb, Hubble space telescopes will try to watch DART asteroid impact

The Sept. 26 smashup will be quite the event.

When NASA's DART mission slams itself into an asteroid called Dimorphos next week, three different science spacecraft will be trying to watch the action.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission is designed to test a planetary defense technique that could be put to use if humans discover a large asteroid on a collision course with Earth. The spacecraft carried with it a tiny cubesat to document its dramatic end, but three other eyes in the sky will also attempt to watch the impact: the James Webb and Hubble space telescopes and another NASA asteroid mission, Lucy.

"This is a unique opportunity and a unique moment to take all the resources that we possibly can to maximize what we've learned," Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Baltimore and the coordination lead for DART, said during a news conference held on Sept. 12.

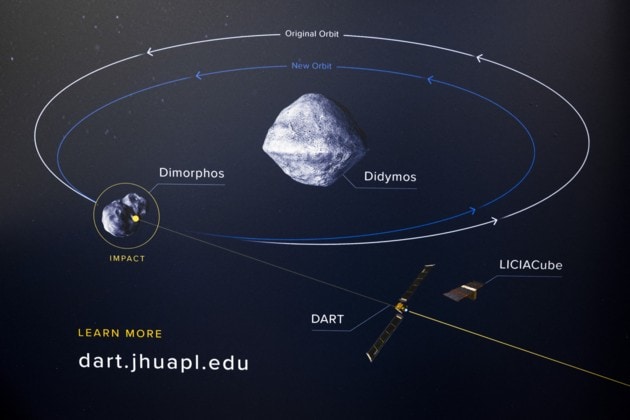

DART launched in November 2021, bound for a binary asteroid system anchored by the larger Didymos, which a moonlet called Dimorphos orbits every 11 hours and 55 minutes. On Monday (Sept. 26), DART will test a technique called kinetic impact, a fancy term for slamming something large enough and fast enough into an asteroid to nudge its orbit.

Scientists want to observe a known impact event to understand how a future planetary defense mission might unfold, should humans want to deflect an asteroid headed toward colliding with Earth. (Neither Didymos nor Dimorphos poses an impact threat to Earth, and nothing that happens on Monday can change that, DART team members stress.)

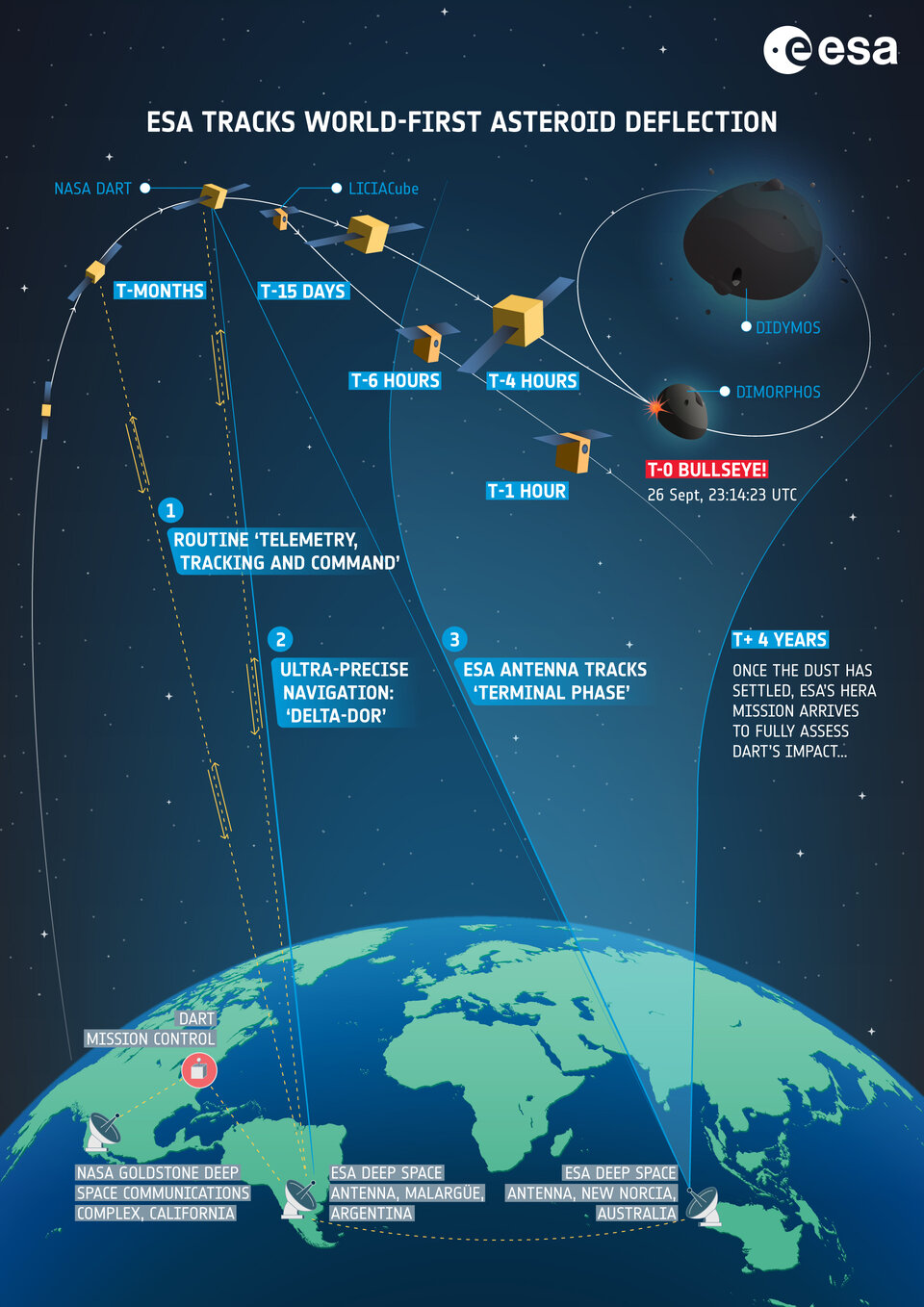

Mission personnel hope to see images of the impact site just three minutes after launch, thanks to the tiny cubesat, LICIA Cube, that DART deployed earlier this month; the European Space Agency will also send a separate mission, Hera, to study the site in detail beginning in late 2026.

But a live view of the moment of impact itself from a telescope in space, unhindered by the blur of Earth's atmosphere, would certainly be a nice bonus. So NASA will turn the veteran Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which just began operations this summer, to try to catch DART's impact, which will occur at 7:14 p.m. EDT (2314 GMT).

How good these space-based observations turn out to be is still unknown. "Let me just stress here, this is not what JWST is designed to do; this is a challenging measurement for them," Chabot said. Dimorphos is much closer and moves much faster than the distant galaxies at the heart of JWST's work. "They will be looking; we'll see what they get."

JWST faces a second challenge, which is that the telescope has to regularly check in on guide stars and readjust, which means its observations might begin a few minutes after impact, Tom Statler, DART program scientist, said during a news conference held Thursday (Sept. 22).

Hubble has its own constraints, since the telescope will be on the wrong side of Earth at the moment of impact, but it will begin observations about 15 minutes after impact. "Hubble won't actually catch the exact moment of impact," Statler said. "That's OK because we don't really expect anything to be really observable from the exact moment of impact."

Along with the two space telescopes, NASA personnel have also arranged for instruments aboard the Lucy mission to observe the impact. Lucy launched in October 2021 to study asteroids that orbit the sun at the same distance as Jupiter and that scientists think hold clues about the earliest days of solar system history.

But for now, Lucy is still near Earth, since it must conduct a flyby next month to set its trajectory out to its targets, so it might be able to catch the impact. (Similarly, in May, the spacecraft took the opportunity to watch the moon disappear during a total lunar eclipse.) At the time of impact, Earth will be about 6.8 million miles (11 million kilometers) away from Didymos; Lucy will be about twice as far away and at a different viewing angle, Statler noted.

Although DART personnel only need to measure the change in Dimorphos' orbit to determine whether the mission was a success, scientists are hoping to learn more about countless other characteristics of the moonlet, including its rotation and structure.

In addition to the immediate aftermath of the impact, the telescopes will also check up on Dimorphos occasionally until about the end of the year, Thomas said, augmenting continuing observations from the ground.

However the spacecraft observations fare, the rest of us will have to watch from the comfort of Earth. And there will be something to watch: NASA has set up a specific video feed that will livestream DART's views of Dimorphos as it speeds to impact, with a new image sent each second until the spacecraft goes dark.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 26.09.2022

.

DART Tests Autonomous Navigation System Using Jupiter and Europa

After capturing images of one of the brightest stars in Earth’s night sky, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test’s (DART) camera recently set its sights on another eye-catching spectacle: Jupiter and its four largest moons.

As NASA’s DART spacecraft cruises toward its highly-anticipated Sept. 26 encounter with the binary asteroid Didymos, the spacecraft’s imager — the Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation, or DRACO — has snapped thousands of pictures of stars. The pictures give the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) team leading the mission for NASA the data necessary to support ongoing spacecraft testing and rehearsals in preparation for the spacecraft’s kinetic impact into Dimorphos, the moon of Didymos.

As the only instrument on DART, DRACO will capture images of Didymos and Dimorphos; it will also support the spacecraft's autonomous guidance system — the Small-body Maneuvering Autonomous Real Time Navigation (SMART Nav) — to guide DART to impact.

On July 1 and August 2 the mission operations team pointed the DRACO imager to Jupiter to test the SMART Nav system. The team used it to detect and target Jupiter’s moon Europa as it emerged from behind Jupiter, similar to how Dimorphos will visually separate from the larger asteroid Didymos in the hours leading up to impact. While the test obviously didn’t involve DART colliding with Jupiter or its moons, it did give the APL-led SMART Nav team the chance to assess how well the SMART Nav system performs in flight. Before this Jupiter test, SMART Nav testing was done via simulations on the ground.

The SMART Nav team gained valuable experience from the test, including for how the SMART Nav team views data from the spacecraft. “Every time we do one of these tests, we tweak the displays, make them a little bit better and a little bit more responsive to what we will actually be looking for during the real terminal event,” said Peter Ericksen SMART Nav software engineer at APL.

The DART spacecraft is designed to operate fully autonomously during the terminal approach, but the SMART Nav team will be monitoring how objects are tracked in the scene, including their intensities, number of pixels, and how consistently they’re being identified. Corrective action using preplanned contingencies will only be taken if there are significant and mission-threatening deviations from expectations. With Jupiter and its moons, the team had a chance to better understand how the intensities and number of pixels of objects might vary as the targets move across the detector.

The image below—taken when DART was approximately 16 million miles (26 million km) from Earth with Jupiter approximately 435 million miles (700 million km) away from the spacecraft—is a cropped composite of a DRACO image centered on Jupiter taken during one of these SMART Nav tests. Two brightness and contrast stretches, made to optimize Jupiter and its moons, respectively, were combined to form this view. From left to right are Ganymede, Jupiter, Europa, Io, and Callisto.

“The Jupiter tests gave us the opportunity for DRACO to image something in our own solar system,” said Carolyn Ernst, DRACO instrument scientist at APL. “The images look fantastic, and we are excited for what DRACO will reveal about Didymos and Dimorphos in the hours and minutes leading up to impact!”

DRACO is a high-resolution camera inspired by the imager on NASA's New Horizons spacecraft that returned the first close-up images of the Pluto system and of the Kuiper Belt object Arrokoth.

DART was developed and is managed by APL for NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office. DART is the world's first planetary defense test mission, intentionally executing a kinetic impact into Dimorphos to slightly change its motion in space. While no known asteroid poses a threat to Earth, the DART mission will demonstrate that a spacecraft can autonomously navigate to a kinetic impact on a relatively small target asteroid, and that this is a viable technique to deflect a genuinely dangerous asteroid, if one were ever discovered. DART will reach its target on September 26, 2022.

Quelle: NASA

+++

Monday, Sept. 26 (DART Impact Day)

Media interested in covering the DART impact from APL must complete this form by 3 p.m. on Friday, Sept. 2.

- 6 p.m. – Live coverage of DART’s impact with the asteroid Dimorphos will air on NASA TV and the agency’s website. The public also can watch live on agency social media accounts on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

- 7:14 p.m. – DART’s kinetic impact with asteroid Dimorphos.

- 8 p.m. – Media briefing at Johns Hopkins APL to hear from mission experts immediately following DART’s successful impact with asteroid Dimorphos. Media interested in receiving details for remote participation must RSVP by 12 p.m. on Monday, Sept. 26 to: alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov.

Quelle: NASA

+++

Kollision in elf Millionen Kilometern Entfernung

- Die NASA-Raumsonde DART wird am 27. September 2022 um 1.14 Uhr MESZ das Asteroiden-Binärsystem Didymos-Dimorphos erreichen und gezielt auf dem Asteroiden Dimorphos einschlagen.

- Die Sonde wird den 170 Meter großen Begleiter des knapp 800 Meter großen Asteroiden Didymos mit fast 22.000 Kilometern pro Stunde treffen.

- Es ist der erste Versuch in der Geschichte der Raumfahrt, die Umlaufbahn eines Himmelskörpers zu verändern.

- Schwerpunkte: Raumfahrt, Exploration, Asteroidenabwehr

Die im letzten Jahr gestartete NASA-Raumsonde DART soll in der Nacht von Montag auf Dienstag erproben, ob es möglich ist, den Kurs eines Asteroiden zu verändern. DART wird dann das Asteroiden-Binärsystem Didymos-Dimorphos erreichen und gezielt auf dem 170 Meter großen Planetoiden Dimorphos einschlagen. Durch den dabei übertragenen „kinetischen Impuls“ soll die Bahn dieses Asteroiden um Didymos verändert werden. Es ist das erste Mal in der Geschichte der Raumfahrt, dass versucht wird, die Bahn eines Himmelskörpers durch einen menschengemachten Körper zu beeinflussen. Das Deutsche Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) ist an der Analyse des Impakts beteiligt. 2026 soll die ESA Mission Hera, an der Deutschland wesentlich über die Deutsche Raumfahrtagentur im DLR beteiligt ist, das Asteroidensystem und dessen Veränderung erkunden.

Die Erde wird von jeher durch Asteroiden bedroht. Zwar bewegen sich fast alle der ungefähr eine Million bekannten, über einhundert Meter großen Himmelskörper auf stabilen Bahnen zwischen Mars und Jupiter. Doch haben davon etwa dreißigtausend Asteroiden solche Bahnen, die sich mit der Umlaufbahn der Erde um die Sonne schneiden und diese Körper Planeten kollidieren können. Bei einer Kollision eines auch nur wenige hundert Meter großen Körpers mit der Erde würde es zu ganz erheblichen Schäden kommen. Mit Raumsonden könnte diese Gefahr abgewendet werden, indem der Kurs eines solchen erdbahnkreuzenden Asteroiden sehr frühzeitig so verändert wird, dass er an der Erde vorbeifliegt.

„Wir leben im Zeitalter der Raumfahrt. Dadurch haben wir die Möglichkeit, mit Raumsonden die Bahn eines Asteroiden, der auf die Erde zu stürzen droht, zu verändern“, sagt Dr. Jean-Baptiste Vincent vom DLR-Institut für Planetenforschung. Das DLR beobachtet und charakterisiert seit Jahrzehnten erdbahnkreuzende Asteroiden. „Zum einen versuchen wir, diese kleinen, aber manchmal eben auch gefährlichen Himmelskörper zu charakterisieren, ihre physikalischen Eigenschaften zu verstehen, und zum anderen daraus Schlüsse zu ziehen, wie wir sie abwehren könnten, sollten die Berechnungen ergeben, dass sie in der Zukunft mit der Erde zusammenstoßen“, erklärt Dr. Stephan Ulamec vom DLR-Nutzerzentrum für Weltraumexperimente (MUSC) in Köln.

Veränderung der Umlaufzeit um einige Minuten

Die beiden DLR-Wissenschaftler sind an der NASA-Mission DART („Double Asteroid Redirection Test“) beteiligt. DART ist ein würfelförmiger Satellit mit knapp zwei Metern Kantenlänge und einer Masse von 610 Kilogramm. Die Mission wurde am 24. November 2021 gestartet und auf einer ellipsenförmigen Bahn zu ihrem Ziel, dem Asteroidenpaar Didymos und Dimorphos gelenkt. Didymos, der größere der beiden Körper, hat einen unregelmäßigen Durchmesser von knapp 800 Metern, Dimorphos von etwa 170 Metern. Dimorphos umkreist Didymos – griechisch für Zwilling – in zwölf Stunden in einer Entfernung von 1.200 Metern. Die beiden Asteroiden umrunden zusammen in 25 Monaten die Sonne auf einem Orbit, der sich mit der Erdbahn kreuzt und sie zu potentiell gefährlichen „NEOs“ (Near-Earth Objects) macht. Im Jahre 2003 kamen die beiden Asteroiden der Erde bis auf sechs Millionen Kilometer nahe.

„Wir gehen davon aus, dass sich die Umlaufzeit von Dimorphos um Didymos durch den Impuls von DART um einige Minuten verändert“, prognostiziert DLR-Forscher Stephan Ulamec. „Allerdings wissen wir nicht, wie Dimorphos beschaffen ist“, ergänzt Jean-Baptiste Vincent. „Ist es ein kompakter Körper oder sind seine Bestandteile nur ganz lose zusammengefügt? Ist Dimorphos also eine Art Schutthaufen aus Gesteinsfragmenten, ein ‚Rubble Pile‘, wie wir in der Asteroidenforschung sagen?“ Die Aufgabe der beiden DLR-Wissenschaftler im DART-Team besteht in der Bestimmung der genauen Form des kleinen Asteroiden, seiner genauen Masse und der Analyse des Kraters und der Übertragung des Impulses und der Auswürfe, die beim Einschlag entstehen.

Die Raumsonde wird dabei natürlich vollständig zerstört, aber der Einschlag von DART auf Dimorphos wird von zwei bereits am 11. September erfolgreich ausgesetzten Kleinsatelliten beobachtet. Die beiden LICIACube-Würfel wurden von der Italienischen Weltraumorganisation ASI entwickelt, um nach dem Einschlag von DART im Vorbeiflug Beobachtungen des Asteroiden-Binärsystems Didymos machen zu können. Die Kleinsatelliten werden vor, während und nach dem Impakt direkt mit der Erde kommunizieren. Jeweils zwei Kameras (LUKE und LEIA) sollen den Einschlag bestätigen und Bilder der Auswurfswolke und möglicherweise eines Kraters festhalten. Drei Minuten nach dem Impakt von DART werden sie an Dimorphos vorbeigeflogen sein, sich drehen und noch Aufnahmen der Rückseite von Dimorphos machen, die DART natürlich nicht aus der Nähe zu sehen bekommt. LICIACube ist die erste rein italienische autonome Raumsonde im Weltraum. Auch die im vergangenen Jahr zu den „Trojaner“-Asteroiden auf der Jupiterbahn gestartete NASA-Mission Lucy wird den Einschlag aus 19 Millionen Kilometer Entfernung beobachten.

Können wir in Zukunft Asteroiden ablenken?

Der gezielte Zusammenstoß der DART-Raumsonde mit Dimorphos wird am 27. September 2022 um 1.14 Uhr MESZ in knapp über elf Millionen Kilometer Entfernung von der Erde geschehen, der kürzesten Entfernung, die das Doppelasteroidensystem in unserer Zeit mit der Erde haben kann (erst 2062 wird das Asteroidenpaar in einer ähnlich geringen Entfernung an der Erde vorbeikommen). Damit sind auch gute Beobachtungsmöglichkeiten für Teleskope auf der Nachtseite der Erde, insbesondere von Europa aus gegeben, die für begleitende Untersuchungen während und nach der Kollision genutzt werden. Auch in den Nächten nach dem Ereignis werden Teleskope Lichtkurven des Binärsystems aufzeichnen, um Daten zu der Bahnveränderung von Dimorphos in die Analyse einzubringen.

Beim Einschlag von DART auf Dimorphos werden fast 140 Millionen Kilojoule Energie umgesetzt. Die Forscher gehen davon aus, dass der Impakt einen Krater von wenigen Zehnermetern Durchmesser erzeugt und sich die Umlaufzeit des Asteroiden messbar, um wenige Minuten verändert. Das entspricht in etwa einer Geschwindigkeitsänderung von einem halben Millimeter pro Sekunde. „Wie effizient die Ablenkung eines Asteroiden durch den Zusammenstoß mit einer Raumsonde ist, wird entscheidend durch die physikalischen Eigenschaften des Körpers beeinflusst, also wie porös und fest das Gestein ist“, erläutert Prof. Dr. Kai Wünnemann vom Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, der mit seinem Team Computersimulationen des Einschlagprozesses erstellt, um möglichst präzise Vorhersagen zu treffen. Am Museum für Naturkunde Berlin werden verschiedene Szenarien der Beschaffenheit von Dimorphos durchgespielt und simuliert, um unter anderem die Kratergrößer zu prognostizieren.

Für die genaue Untersuchung des Einschlags und seiner Folgen wird im Oktober 2024 die mit der NASA abgestimmte Mission Hera der Europäischen Weltraumorganisation ESA gestartet, die maßgeblich in Deutschland entwickelt und gebaut wird. Die Deutsche Raumfahrtagentur im DLR mit Sitz in Bonn managt die deutschen ESA-Beiträge für Hera. Im Dezember 2026 wird Hera das Doppelasteroidensystem erreichen, also etwa vier Jahre nach dem Aufprall von DART. Heras detaillierte Untersuchungen werden dann das Wissen über die Möglichkeiten einer Asteroidenabwehr erheblich erweitern. DART und Hera sind Missionen des internationalen Forschungsprojekts AIDA (Asteroid Impact and Deflection Assessment).

Immer wieder Asteroidentreffer in der Erdgeschichte

Für die vor uns liegenden Jahrzehnte gibt es gegenwärtig keinen Anlass zur Sorge, dass ein Asteroid die Erde trifft. Doch dies geschah in der viereinhalb Milliarden Jahre langen Geschichte der Erde immer wieder. Spuren davon sind Krater, die beim Einschlag von Asteroiden zurückbleiben, wie das Nördlinger Ries in Süddeutschland oder der Barringer-Krater in Arizona. Der von Einschlagskratern übersäte Mond macht deutlich, dass Asteroidenkollisionen früher viel häufiger waren – auf der dynamisch sich ständig verändernden Erde sind fast alle Spuren von Einschlägen ausgelöscht. Das Aussterben der Dinosaurier ist vor 65 Millionen Jahren durch einen Asteroidentreffer ausgelöst worden.

Dass die Gefahr von Asteroidentreffern auf der Erde auch heute, wenn auch in viel geringerem Maße, real bleibt, wurde am 15. Februar 2013 deutlich. Damals trat ein unbekannter Asteroid in die Erdatmosphäre ein und explodierte über der russischen Stadt Tscheljabinsk. Die Schockwelle der komprimierten Luft der Erdatmosphäre verursachte erhebliche Schäden in der Stadt. Tausende von Fensterscheiben barsten, dabei wurden mehr als 1.600 Menschen verletzt. Der Gesamtschaden wurde auf 30 Millionen Euro geschätzt. Dabei war das Objekt in Tscheljabinsk nur etwa 18 Meter groß.

Quelle: DLR

----

Update: 27.09.2022

.

EHR-TEST DART

NASA lenkte Sonde gezielt in Asteroid Dimorphos

Großer Erfolg für die US-Raumfahrtbehörde NASA: Am Dienstag gelang es ihr, im Rahmen des Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) eine Sonde absichtliche mit einem Asteroiden kollidieren lassen, um diesen von seinem Kurs abzubringen. Die Sonde schlug wie geplant um 1.16 Uhr MESZ auf der Oberfläche des Asteroiden Dimorphos (siehe Video oben) auf.

Die DART-Sonde war im November 2021 an Bord einer „Falcon 9“-Rakete von Kalifornien aus zu ihrer rund zehnmonatigen Reise zum Asteroiden gestartet. Aber erst rund eineinhalb Stunden vor dem Aufprall konnten sie Dimorphos mit ihrer Kamera ins Visier nehmen. Die Annäherung des Raumfahrzeuges wurde bis zu dessen Aufprall live gestreamt.

Auf den von der Kamera der Sonde zur Erde übertragenen Bildern wurde der Asteroid Dimorphos erst rund eine Stunde vor dem Einschlag als heller Punkt sichtbar, wurde immer größer und war schließlich mit Oberflächendetails und Schattierungen zu sehen - bis die Kamera beim Einschlag zerstört wurde und das Bild daher eine rote Störung anzeigte.

Autopilot steuerte Sonde in Asteroiden

Im Kontrollzentrum der NASA brach daraufhin Jubel aus, das Team klatschte und umarmte sich gegenseitig. Bis kurz vor Aufprall war man nicht ganz sicher gewesen, ob die mit einer Geschwindigkeit von rund 6,6 Kilometern pro Sekunde (23.760 Kilometer pro Stunde) fliegende Sonde von der Größe eines Getränkeautomaten, die die letzten Minuten im Autopilot unterwegs war, den Asteroiden, der einen Durchmesser von rund 160 Metern hat, auch wirklich treffen würde.

Laut Angaben der NASA-Forscher handelt es um einen ersten vorsichtigen Versuch, ob es möglich sein könnte, die Flugbahn eines Asteroiden auf diese Weise abzuändern. Man erhofft sich von der Mission Erkenntnisse darüber, wie die Erde vor herannahenden Asteroiden geschützt werden könnte. Es stehe nicht weniger als die „zukünftige Sicherheit der Erde auf dem Spiel“, hieß es im Vorfeld des Tests.

Aufprall soll die Umlaufbahn verändern

Nach dem Aufprall soll die rund zwölfstündige Umlaufbahn von Dimorphos um mindestens 73 Sekunden und möglicherweise bis zu zehn Minuten kürzer dauern. Für die Wissenschaftler geht die Arbeit aber erst jetzt richtig los: Mit Teleskopen auf aller Welt beobachten und analysieren sie, was genau vor, während und nach dem Aufprall passiert ist - und was das nun für den Schutz der Erde bedeuten könnte. 2024 soll zur noch genaueren Untersuchung dann die ESA-Mission „Hera“ starten.

Didymos ist nah genug, um all das mit wissenschaftlichen Instrumenten von der Erde und vom Weltraum aus zu beobachten und zu messen. Der Asteroid stellt derzeit den Berechnungen der NASA-Forscher zufolge keine Gefahr für die Erde dar - und die Mission ist so angelegt, dass der Asteroid auch nach dem Aufprall der Sonde keine Gefahr darstellen sollte. 2024 soll die ESA-Mission „Hera“ starten, um die Auswirkungen des Aufpralls genauer zu untersuchen.

Beide Asteroiden keine Gefahr für die Erde

Dimorphos mit einem Durchmesser von rund 160 Metern ist eine Art Mond des größeren Asteroiden Didymos. Die Mission ist so angelegt, dass beide Asteroiden auch nach dem Aufprall der Sonde, die nur eine Kamera an Bord hatte, keine Gefahr für unseren Planeten darstellen.

Quelle: Kronen Zeitung

+++

Hera team congratulates NASA asteroid impactors

ESA’s Hera mission team congratulates their counterparts in NASA’s DART mission team for their historic impact with the Dimorphos asteroid. Moving at 6.1 km per second, the vending-machine-sized Double Asteroid Redirect Test spacecraft struck the 160-m diameter asteroid at 01:15 CEST (00:15 BST) in the early hours of Tuesday morning, in humankind’s first test of the ‘kinetic impactor’ method of planetary defence.

Ian Carnelli, Hera mission manager, says: “Making contact with a target that small across 11 million km of space is an impressive technical achievement in itself, tonight a wonderful page of space history has been written. One that we have all been looking forward to for many years. Today our thoughts are also with the late Prof. Andrea Milani who first outlined this deflection test in 2004.

“Next comes a period of sustained observation by ground and space-based telescopes to determine if DART’s impact has indeed achieved what it was intended to do, and move the orbit of the Dimorphos ‘moonlet’ around its parent 780-m diameter Didymos asteroid.

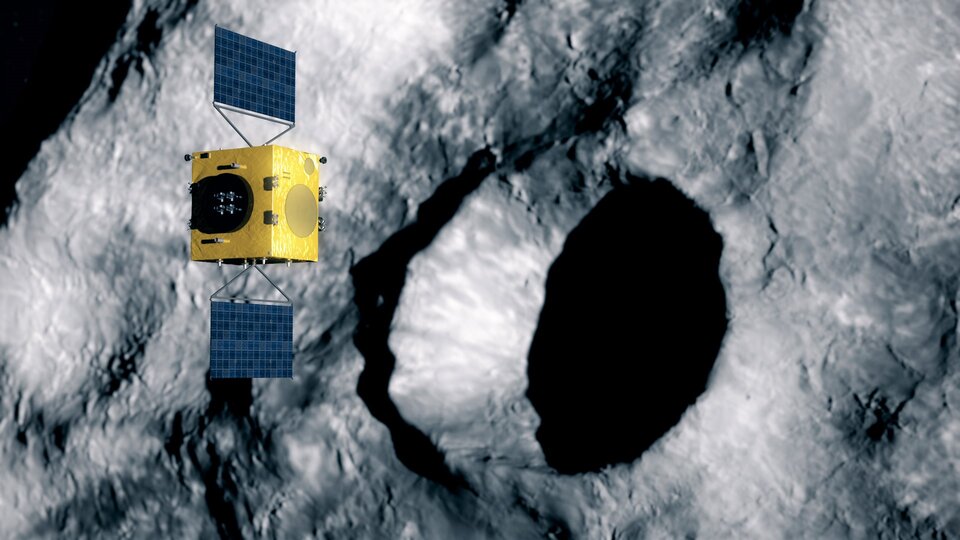

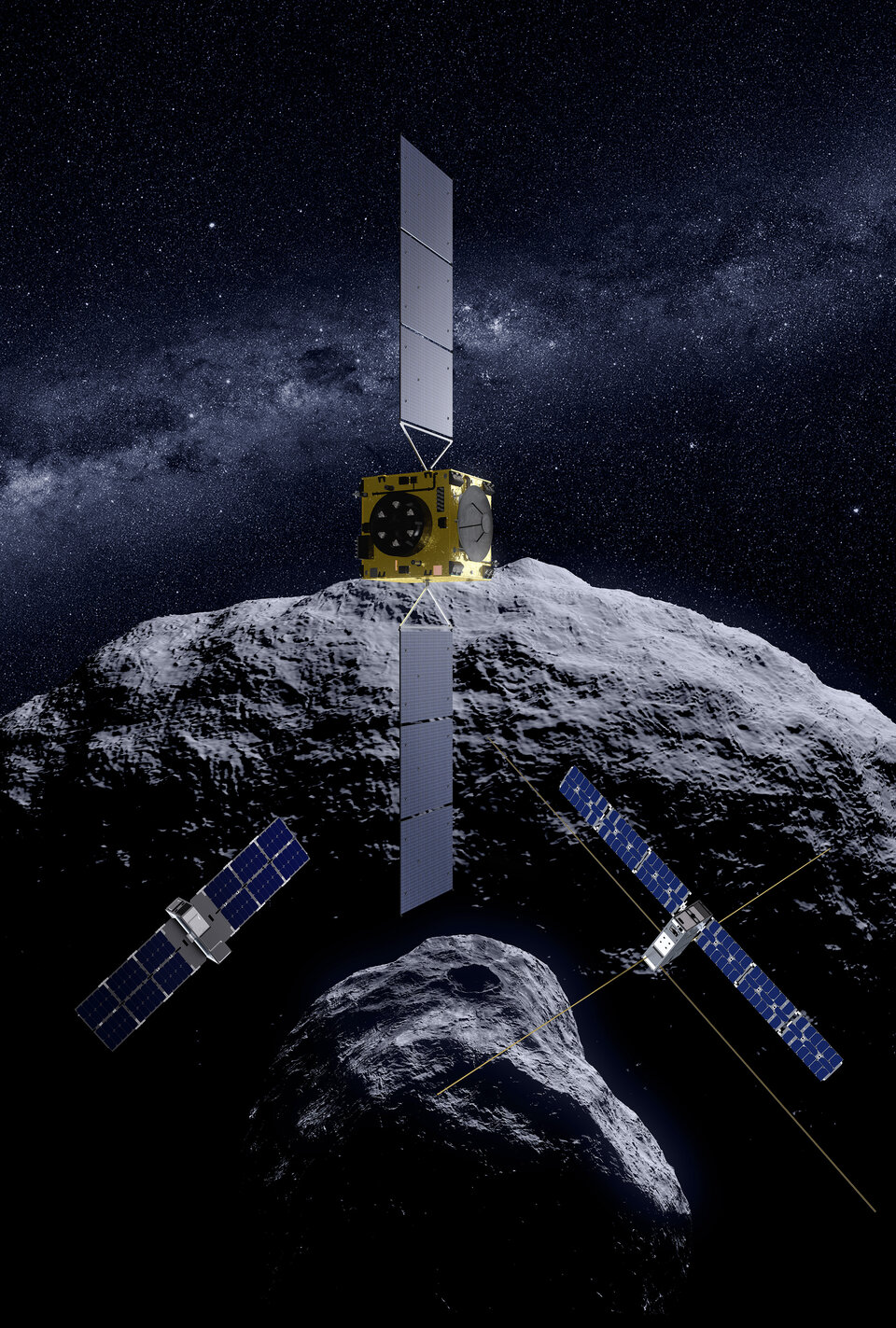

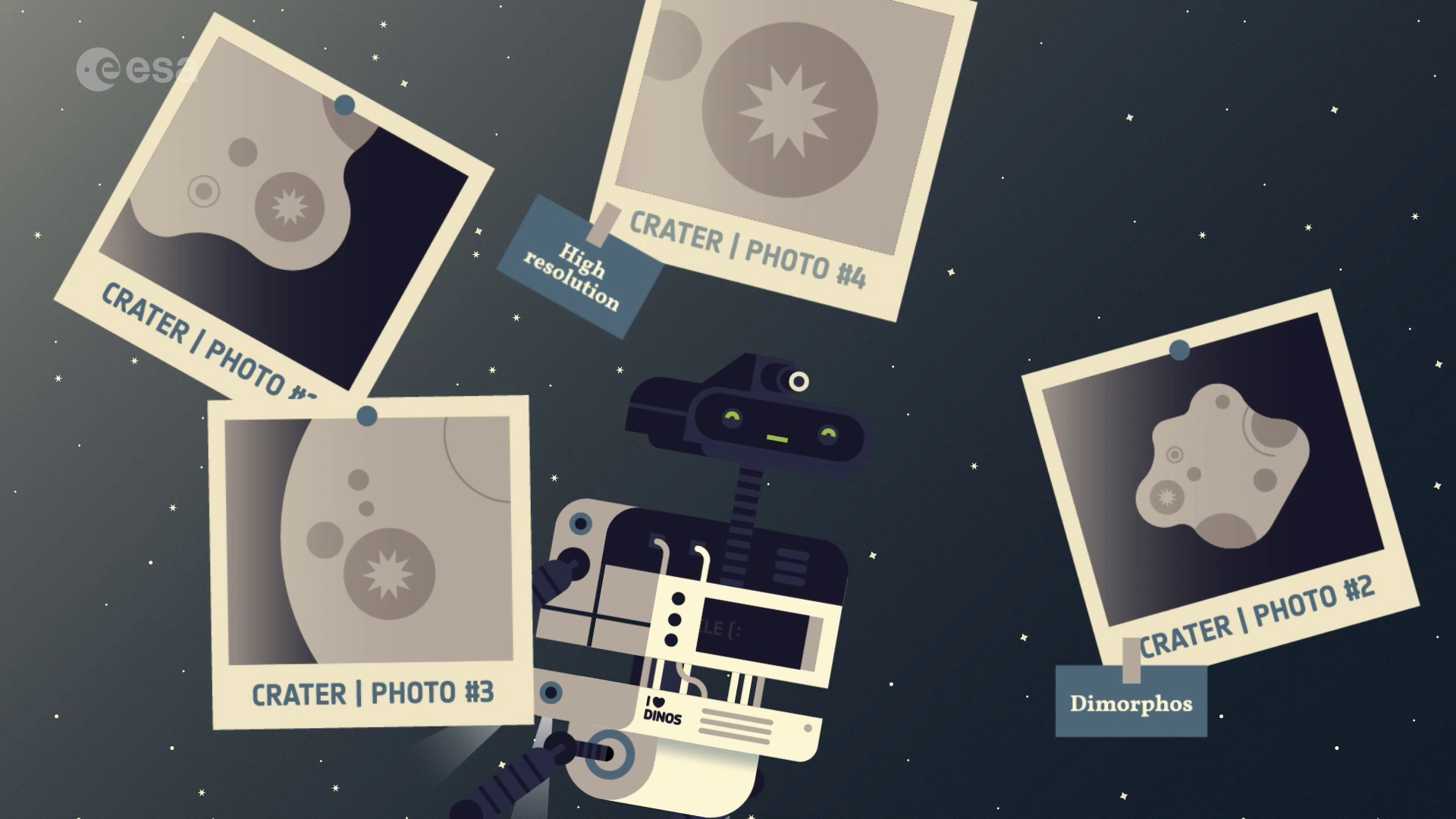

“In parallel, ESA and our industrial partners continue our work to construct the Hera spacecraft, which will launch in late 2024, beginning its own voyage to Dimorphos to perform a close-up survey of the post-impact asteroid. Hera will gather key information such as the size of DART’s crater, the mass of Dimorphos and its make-up and internal structure. This extra data will help turn the DART deflection experiment into a well-understood, repeatable technique that might one day be carried out for real.”

International collaboration

NASA’s DART and ESA’s Hera missions are supported by the same international teams of scientists and astronomers, and take place through an international collaboration called AIDA – the Asteroid Impact and Deflection Assessment. Planetary defence has no borders and is a great example of what international collaboration can achieve.

The missions were conceived together during the early years of the 21st century, when concern about the destructive potential of incoming asteroids led to the creation of the first automated survey systems, resulting in ESA’s Near Earth Object Coordination Centre, NEO-CC and NASA’s Sentry system.

But the space scientists working on the system realised that asteroid threat identification was not sufficient; they also needed to come up with a way of addressing that threat.

Ian explains: “Mathematican and astronomer Andrea Milani of the University of Pisa – a planetary defence pioneer who sadly passed away in 2018 – came up with the idea of a double-spacecraft mission he called ‘Don Quijote’: one spacecraft would impact an oncoming asteroid while the other observer spacecraft would measure the degree of deflection.”

In the event the concept was internationalised, with NASA taking on what would evolve into DART. ESA’s Hera will follow its predecessor into space in 2024, arriving at Dimorphos two years later. Its target asteroid will hold special significance as the first body in the Solar System to have had both its surface and its orbit modified by human intervention in a measurable way. Its name taken from the Greek for ‘having two forms’.

ESA’s Hera spacecraft taking shape

Hera’s payload module is currently taking shape at OHB in Germany while its propulsion module is finalised at Avio in Italy, with companies and institutions across 17 European countries making their own contribution to the mission – such as GMV in Spain, developing the automated guidance, navigation and control system that will allow the spacecraft to safely navigate the double-asteroid system, akin in function to a self-driving car.

The desk-sized Hera is packed with instruments, with its optical Asteroid Framing Camera supplemented by thermal and spectral imagers, as well as a laser altimeter for surface mapping. Hera is also three spacecraft in one, because it will additionally deliver a pair of shoebox-sized ‘CubeSats’ into Dimorphos’ vicinity.

The Juventas CubeSat will perform the first ever radar probe of an asteroid, while also carrying a gravimeter and accelerometer to measure the body’s ultra-low gravity. The other CubeSat, Milani – named after AIDA’s inventor – will perform near-infrared spectral imaging and sample asteroid dust.

The CubeSat pair will remain in contact with their Hera mothership and each other through a novel inter-satellite link system, to build up experience of overseeing multiple spacecraft in exotic near-weightlessness, before eventually touching down on Dimorphos.

Ian concludes: “Thanks to DART, we’ve had a tantalising glimpse of our destination, now we can’t wait to go back and explore it in depth, to find out how the impact has changed it, and help make Earth a safer place in the process.”

Access the video

NASA’s DART Mission Hits Asteroid in First-Ever Planetary Defense Test

After 10 months flying in space, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) – the world’s first planetary defense technology demonstration – successfully impacted its asteroid target on Monday, the agency’s first attempt to move an asteroid in space.

Mission control at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, announced the successful impact at 7:14 p.m. EDT.

As a part of NASA’s overall planetary defense strategy, DART’s impact with the asteroid Dimorphos demonstrates a viable mitigation technique for protecting the planet from an Earth-bound asteroid or comet, if one were discovered.

“At its core, DART represents an unprecedented success for planetary defense, but it is also a mission of unity with a real benefit for all humanity,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “As NASA studies the cosmos and our home planet, we’re also working to protect that home, and this international collaboration turned science fiction into science fact, demonstrating one way to protect Earth.”

DART targeted the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos, a small body just 530 feet (160 meters) in diameter. It orbits a larger, 2,560-foot (780-meter) asteroid called Didymos. Neither asteroid poses a threat to Earth.

The mission’s one-way trip confirmed NASA can successfully navigate a spacecraft to intentionally collide with an asteroid to deflect it, a technique known as kinetic impact.

The investigation team will now observe Dimorphos using ground-based telescopes to confirm that DART’s impact altered the asteroid’s orbit around Didymos. Researchers expect the impact to shorten Dimorphos’ orbit by about 1%, or roughly 10 minutes; precisely measuring how much the asteroid was deflected is one of the primary purposes of the full-scale test.

“Planetary Defense is a globally unifying effort that affects everyone living on Earth,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Now we know we can aim a spacecraft with the precision needed to impact even a small body in space. Just a small change in its speed is all we need to make a significant difference in the path an asteroid travels.”

The spacecraft’s sole instrument, the Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation (DRACO), together with a sophisticated guidance, navigation and control system that works in tandem with Small-body Maneuvering Autonomous Real Time Navigation (SMART Nav) algorithms, enabled DART to identify and distinguish between the two asteroids, targeting the smaller body.

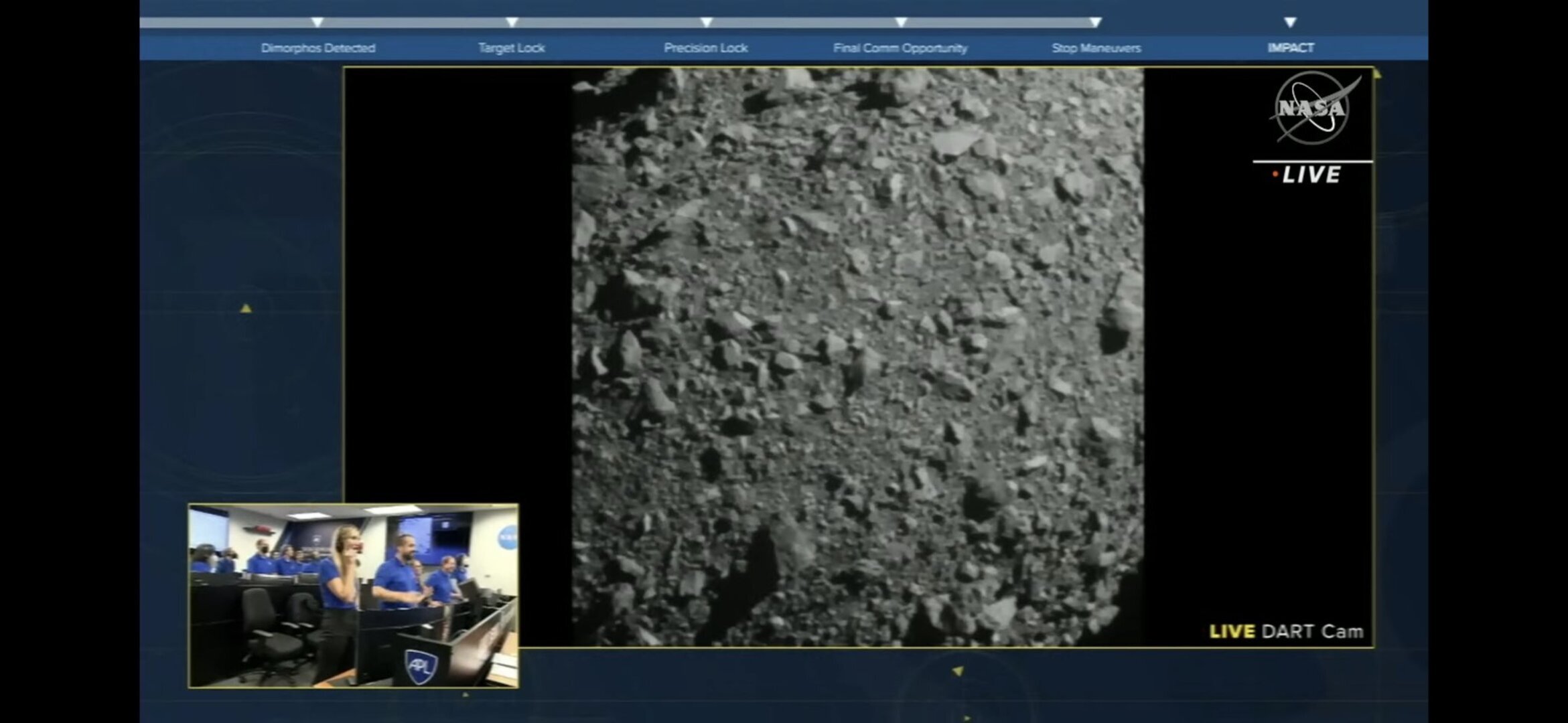

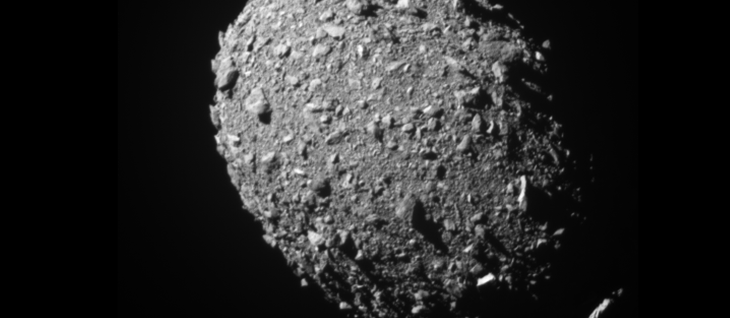

These systems guided the 1,260-pound (570-kilogram) box-shaped spacecraft through the final 56,000 miles (90,000 kilometers) of space into Dimorphos, intentionally crashing into it at roughly 14,000 miles (22,530 kilometers) per hour to slightly slow the asteroid’s orbital speed. DRACO’s final images, obtained by the spacecraft seconds before impact, revealed the surface of Dimorphos in close-up detail.

Fifteen days before impact, DART’s CubeSat companion Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids (LICIACube), provided by the Italian Space Agency, deployed from the spacecraft to capture images of DART’s impact and of the asteroid’s resulting cloud of ejected matter. In tandem with the images returned by DRACO, LICIACube’s images are intended to provide a view of the collision’s effects to help researchers better characterize the effectiveness of kinetic impact in deflecting an asteroid. Because LICIACube doesn’t carry a large antenna, images will be downlinked to Earth one by one in the coming weeks.

“DART’s success provides a significant addition to the essential toolbox we must have to protect Earth from a devastating impact by an asteroid,” said Lindley Johnson, NASA’s Planetary Defense Officer. “This demonstrates we are no longer powerless to prevent this type of natural disaster. Coupled with enhanced capabilities to accelerate finding the remaining hazardous asteroid population by our next Planetary Defense mission, the Near-Earth Object (NEO) Surveyor, a DART successor could provide what we need to save the day.”

With the asteroid pair within 7 million miles (11 million kilometers) of Earth, a global team is using dozens of telescopes stationed around the world and in space to observe the asteroid system. Over the coming weeks, they will characterize the ejecta produced and precisely measure Dimorphos’ orbital change to determine how effectively DART deflected the asteroid. The results will help validate and improve scientific computer models critical to predicting the effectiveness of this technique as a reliable method for asteroid deflection.

“This first-of-its-kind mission required incredible preparation and precision, and the team exceeded expectations on all counts,” said APL Director Ralph Semmel. “Beyond the truly exciting success of the technology demonstration, capabilities based on DART could one day be used to change the course of an asteroid to protect our planet and preserve life on Earth as we know it.”

Roughly four years from now, the European Space Agency’s Hera project will conduct detailed surveys of both Dimorphos and Didymos, with a particular focus on the crater left by DART’s collision and a precise measurement of Dimorphos’ mass.

Johns Hopkins APL manages the DART mission for NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office as a project of the agency's Planetary Missions Program Office.

DART’s Final Images Prior to Impact

After 10 months flying in space, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) – the world’s first planetary defense technology demonstration – successfully impacted its asteroid target Dimorphos on Monday, Sept. 26, 2022, the agency’s first attempt to move an asteroid in space. During the spacecraft’s final moments before impact, its Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation (DRACO) imager took four images capturing its terminal approach as Dimorphos increasingly fills the field of view.