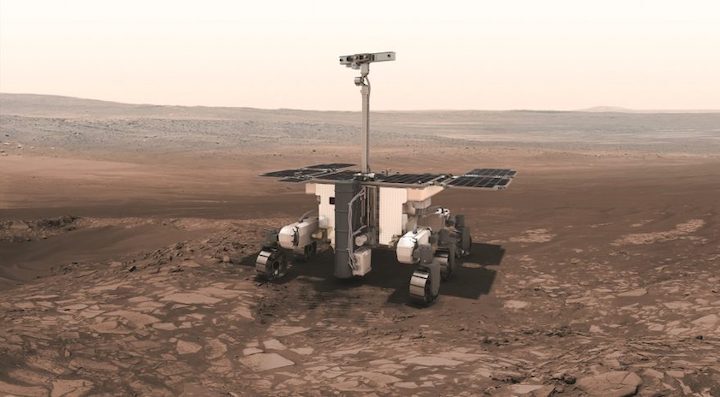

It has cost £840m to develop and taken 15 years to build. But now fears are mounting that the British-built robot rover – which was to have flown on Europe’s ExoMars mission in September – may never make it to the red planet.

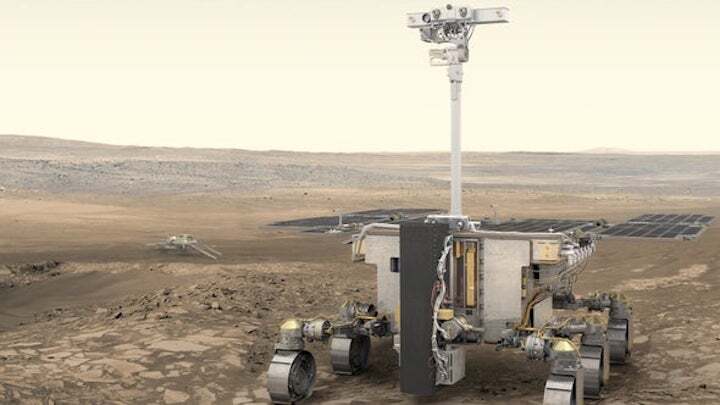

The alternative would be to find another launcher. However, such a move poses other problems. Russia was also supplying the Kazachok lander that was to settle the Rosalind Franklin safely on the planet’s surface. “First, a huge parachute would have decelerated the craft as it descended through the Martian atmosphere. Then Kazachok’s retro rockets would have further slowed it down so the rover could land gently,” said Professor Andrew Coates, of University College London.

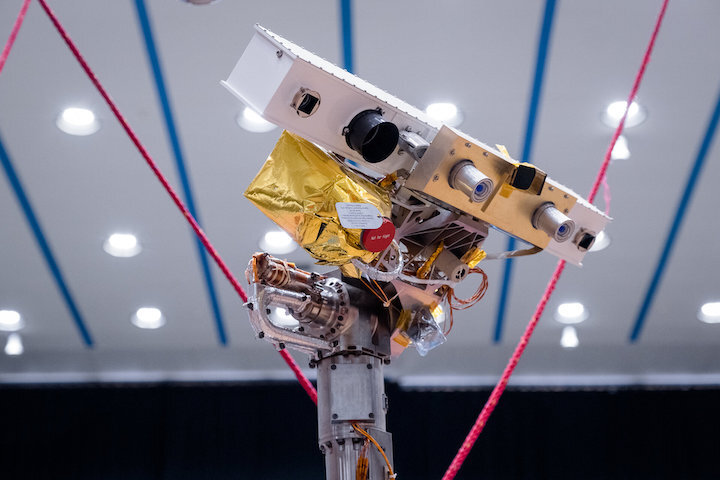

“It is an extremely tricky, complex manoeuvre and designing a replacement landing system will not be easy,” added Coates, who is principal investigator for the rover’s panoramic camera experiment.

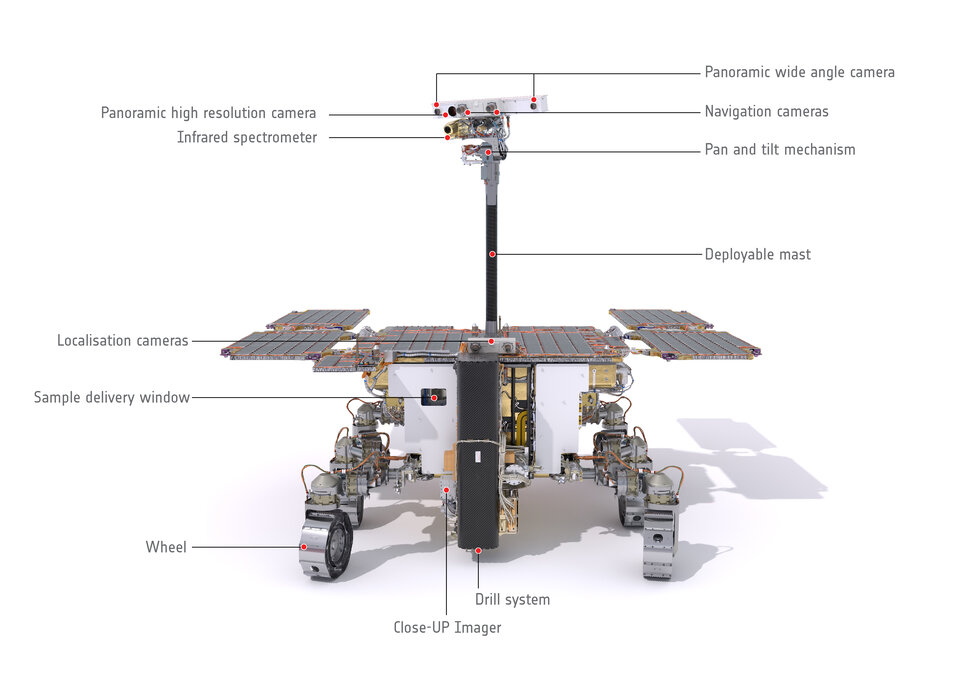

Previous Martian rovers have managed to scrape soil samples from a depth of only about 6cm. “That is the key feature of this mission,” said Coates. “We will be bringing samples from depths of two metres, where any signs of life are going to be better protected from the cosmic rays that batter Mars’ surface.”

Several dozen planetary scientists in Britain have been involved in work on ExoMars – including Áine O’Brien, at Glasgow University.

While some scientists remain relatively optimistic that Europe and Russia might cooperate in space again, others remain doubtful.

“If it ends up being postponed until the end of the decade, as we hunt for new launchers and develop new landing systems, then the mission will all start to look old,” said Robert Massey of the Royal Astronomical Society. “That is why there is speculation now that it might never fly.”

This view was backed by O’Brien: “In the end, we may have to cut our losses and concentrate on other Mars missions.”

Nor is ExoMars likely to be the only casualty of the invasion of Ukraine. Russia provides relatively cheap but powerful rockets that have been used to launch many European missions in the past. Immediate victims of the suspension of future launches will include two Galileo navigation satellites , while The ESA’s EarthCare science mission, developed in cooperation with the Japanese space agency, Jaxa, and the Euclid infrared space telescope will also be affected.

More perplexing is the likely impact on the International Space Station, which relies on a Russian propulsion system to boost away from Earth as its orbit decays and to move it to avoid space debris. Should Russia pull out of the ISS, then the vast orbiting laboratory would slowly spiral lower and lower until it crashed.

This threat was recently made explicit by Dmitry Rogozin, the head of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos. Russia would determine on its own “how long the ISS will operate”, he told the country’s state news agency, Tass.

Quelle: The Guardian

----

Update: 9.04.2022

.

ESA continues talks with NASA on ExoMars cooperation

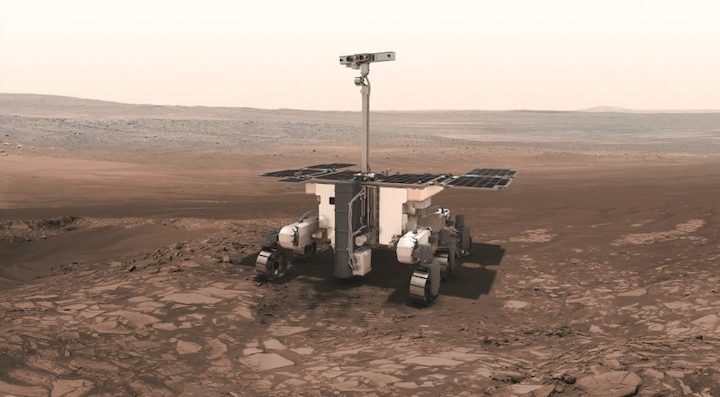

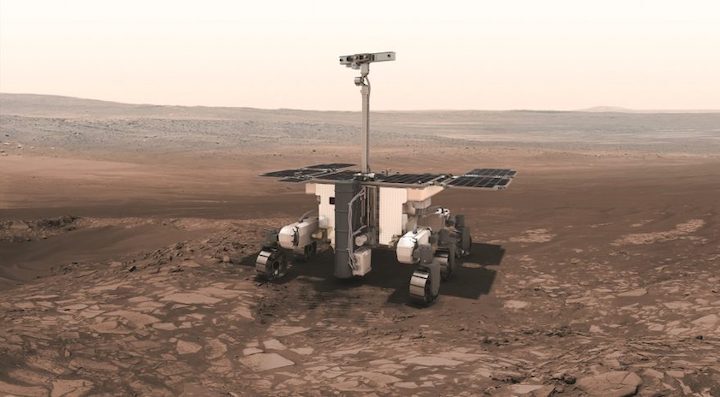

ESA Director General said ESA is continuing discussions with NASA about how NASA could help replace Russian elements of the ExoMars mission, while also considering European alternatives. Credit: Tom Kimmell Photography

COLORADO SPRINGS — The European Space Agency is continuing discussions with NASA on how the agencies can work together to revive ESA’s ExoMars mission after ending cooperation with Russia.

ESA announced March 17 it halted plans to launch the mission, featuring a European-built rover, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia was to launch the mission on a Proton rocket and provide a landing platform and other components.

“It was not an easy decision,” Josef Aschbacher, director general of ESA, said during a panel of space agency leaders at the 37th Space Symposium April 6. Scientists and engineers had worked for years on the mission and the rover now is nearly complete. At the time of the decision to suspend work with Russia, it being prepared to ship to the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

He thanked NASA for contacting ESA and offering assistance on ExoMars, adding in a later interview that discussions between the agencies are continuing. “Our teams are working with the teams in NASA about the technical steps that need to be done,” he said.

The agencies are looking at options for replacing the Russian elements of ExoMars, such as the launch vehicle and landing platform. Other components that Russia was providing were radioisotope heating units to keep the rover warm at night, a technology commonly used by NASA but which for ESA is much less mature.

Another option ESA is pursuing is to replace Russian components with European ones. Aschbacher said studies are ongoing on technical and financial aspects of both strategies, which should be completed by June. “By July, I expect to have a decision from my member states,” he said, which would become part of the package for ESA’s ministerial meeting late this year.

ESA is also studying options for launching missions that were to fly on Soyuz rockets from French Guiana that were stranded by Russia’s decision in February to halt such launches. Those missions include two pairs of Galileo navigation satellites, two ESA science missions and a French reconnaissance satellite.

Aschbacher said ESA is study ways to launch those satellites using Ariane 6 and Vega C launch vehicles, both of which are scheduled to make their inaugural launches this year. That will depend in part on an ongoing assessment of ramping up Ariane 6 launches expected to be done in a month. At that point, he said ESA will be able to better determine how to launch those payloads.

“One option might be that we have to look, for a limited period of time, at backup launcher options,” he said, which would include non-European launch vehicles. “I would expect this would be a very limited period where we would need such solutions and then we can fully rely on Ariane 6.”

Aschbacher, like NASA officials, said that International Space Station operations remain unaffected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and that ESA was preparing proposals to extend its role on the ISS through 2030. “We’re working toward the normal continuation of the operations of the ISS.”

Aschbacher said on the panel that, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian government asked to join ESA. “This is a big decision and not something that can be done very quickly,” he said in the interview, with a years-long process that nations must follow to become full members. “This is not something that will happen tomorrow.”

He said ESA was considering ways it could assist Ukraine in the near term, such as providing satellite data to support damage assessments and agriculture. “I would expect significant financial support from the West in rebuilding Ukraine, and space can help with that.”

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 5.05.2022

.

ExoMars official says launch unlikely before 2028

An ESA official said it's unlikely the agency would be ready to launch the ExoMars rover until at least 2028, and that date could require assistance from NASA on key technologies. Credit: ESA

WASHINGTON — A key official for Europe’s ExoMars mission believes that the rover’s launch will be pushed back until at least 2028 to accommodate changes after ending cooperation with Russia.

ExoMars was to launch in September on a Proton rocket through a partnership between Roscosmos and the European Space Agency. Roscosmos also provided the landing platform for the ESA-built Rosalind Franklin rover.

However, ESA announced March 17 it was suspending cooperation with Russia on ExoMars in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That requires ESA to find not just a new launch for the mission but also replacing the landing platform. That meant pushing the launch back to at least 2026, ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher said at the time, adding that “even that is very challenging.”

Speaking at a May 3 meeting of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG), Jorge Vago, ExoMars project scientist at ESA, said he doubted a new lander could be ready by 2026. “It is theoretically possible, but in practice we think it would be very difficult to reconfigure ourselves and produce our own lander for 2026,” he said. “Realistically, we would be looking at a launch in 2028.”

Launching in 2028 could pose technical challenges for ExoMars. One trajectory would get the rover to Mars relatively quickly, but have it arrive just a month before dust storm seasons starts at the preferred landing site. An alternative trajectory would require traveling for more than two years to each Mars, but get the rover there six months before dust storms start.

“We have been trying very hard to convince the engineering team that the dust storm season is not death,” Vago said. “We should concentrate on making the rover more robust and able to weather a dust storm.”

A 2028 launch, he added, would require assistance from NASA. Specifically, he said ESA would need descent engines similar to those produced by Aerojet Rocketdyne for NASA Mars missions like Curiosity and Perseverance, because there are not European models the right size for ExoMars.

A second item is radioisotope heating units, or RHUs, which use the heat produced from the radioactive decay of plutonium to keep the rover warm. Russia had provided RHUs for the rover, and there is no European replacement. Using American RHUs would likely also require that ExoMars launch from the United States, he said.

Aschbacher said in an April 6 interview that ESA was working with NASA on potential cooperation with ExoMars while also looking at replacing Russian components of the mission with European alternatives. That will lead to a decision in July on a path forward for ExoMars, which would likely require additional funding that would be requested at ESA’s next ministerial meeting late this year.

A delay to 2028 would mean ExoMars would be launching at the same time as the two landers for the revised Mars Sample Return (MSR) campaign that NASA and ESA are jointly conducting. ESA’s contributions include a rover that would go on one of the landers to pick up samples cached by Perseverance, placing them into a rocket on the other lander that would place the samples in Mars orbit to be picked up and returned to Earth by an ESA orbiter.

That’s led to some speculation in the Mars exploration community that the Rosalind Franklin rover could be repurposed to support the Mars Sample Return effort. Vago said he expected some kind of “quid pro quo” arrangement between NASA and ESA if NASA assisted ESA on ExoMars. That could mean, he said, to “look at both MSR and ExoMars in sort of a holistic way, if you like, and see if we can find solutions that work for both missions.”

A unique aspect of the Rosalind Franklin rover is a drill that can collect samples from up to two meters below the surface. A similar drill is proposed for Mars Life Explorer, a Mars lander concept endorsed by the recent planetary science decadal survey for launch no earlier than the mid-2030s to look for signs of life in subsurface ice deposits. During MEPAG discussions May 2, some suggested a rover-mounted drill, like that for ExoMars, would be more effective than a drill mounted on a stationary lander.

Vago confirmed that the ExoMars drill can handle ice as well as rock, although he said the mixture of ice and rock could complicate processing of the sample.

Quelle: SN ---- Update: 21.05.2022 .

Will NASA Save Europe’s Beleaguered Mars Rover?

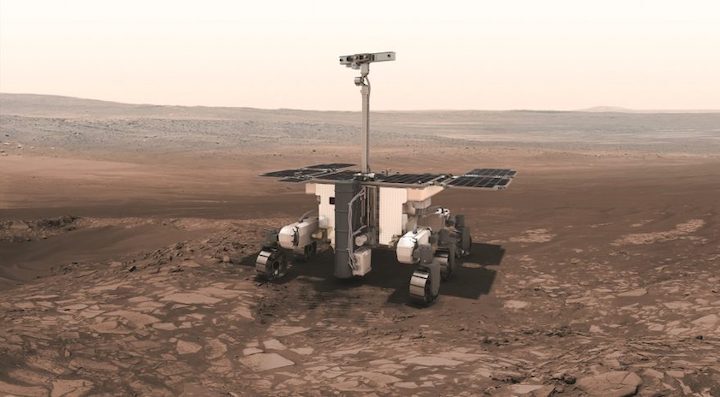

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine ended hopes of launching the ExoMars rover in 2022. Now the mission may never lift off at all

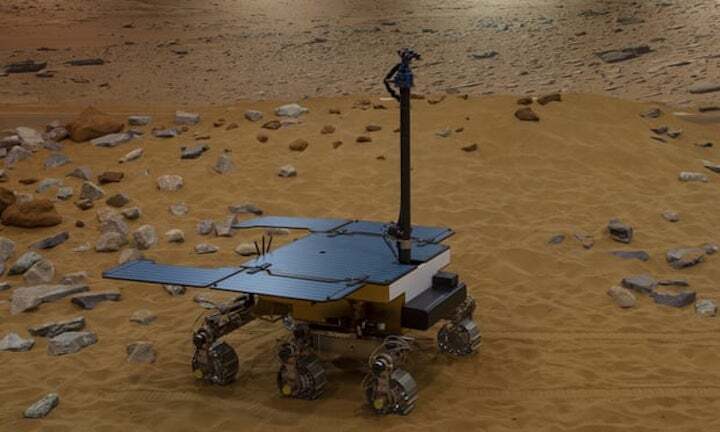

Europe’s long-awaited ExoMars rover—the first ever for the continent—seems to be cursed. Parachute problems scuppered its initially planned launch in 2018. Then the coronavirus pandemic prevented a launch in 2020. And now Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has dashed chances for a liftoff in 2022. For members of the team hoping “the third time’s the charm,” this latest delay feels especially cruel. “It was impossible for me to speak about this mission for weeks without tears,” says Valérie Ciarletti of the Laboratory for Atmospheres, Environments, Space Observations (LATMOS) in France, who leads the rover’s subsurface radar instrument team. After more than 20 years of planning and development, the fully assembled rover sits awaiting launch in a facility in Turin, Italy. Yet it appears increasingly likely that ExoMars will never lift off at all. European Space Agency (ESA) officials are now weighing whether to attempt a launch for a fourth time versus canceling the mission and moving on. The cursed rover may still be saved—but at what cost?

Named Rosalind Franklin after the famed English chemist who discovered the double helix structure of DNA, Europe’s rover would be a significant step forward in the hunt for life on the Red Planet. Whereas NASA’s Perseverance rover, currently exploring an ancient river delta inside Jezero Crater, relies on an elaborate grab-and-go Mars Sample Returnprogram to deliver Martian material back to Earth for astrobiological analysis, the Franklin rover would perform a direct search without needing sample return. It would look deeper, too: Using a drill, it would reach as much as two meters below the surface, where evidence of life is less likely to have been erased by blasts of cosmic radiation. (Neither Perseverance nor its near-twin the Curiosity rover are equipped to probe such depths.) “The ExoMars rover has been built purely with astrobiology in mind,” says Melissa McHugh of the University of Leicester in England, who is part of the science team for the rover’s laser spectrometer instrument. “What’s underneath the surface of Mars has huge biological implications.”

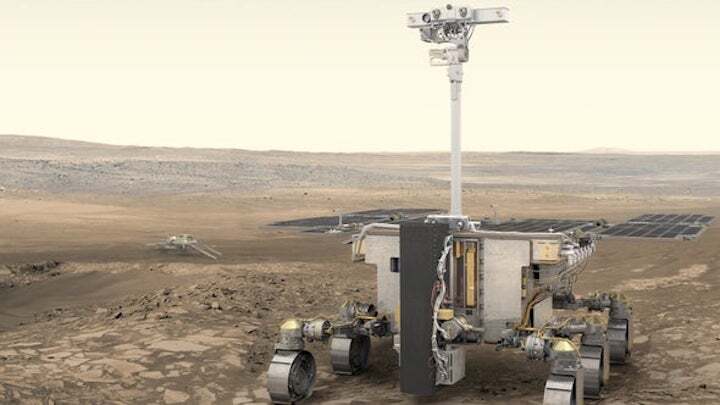

If all had gone to plan earlier this year, the Franklin rover would have launched on a Russian Proton rocket in September before it was lowered to the surface by a Russian powered landing platform called Kazachok in June 2023. But on March 17, 2022, following Russia’s widely condemned invasion of Ukraine, ESA chose to cut ties with the nation on the mission, suspending the Franklin rover indefinitely. ESA officials expect to formally decide whether to proceed with the mission by the time of the agency’s ministerial meeting in November 2022.

ROUTES TO THE RED PLANET

One possible route for the rover reaching the Martian surface runs through the U.S., via NASA-supplied components and capabilities to augment a new ESA-built lander replacing Kazachok. “Our teams are working with the teams in NASA about the technical steps that need to be done,” said Josef Aschbacher, director general of ESA, in an interview with SpaceNews in April. In an e-mailed statement to Scientific American, NASA officials confirmed those exploratory efforts: “We have recently begun a joint assessment of options for the ExoMars mission,” they wrote. “Once we know more, we will incorporate that information into our plans.”

Alternatively (and improbably), the mission’s route could still run through Russia. Jorge Vago, the rover’s project scientist at ESA, says repartnering with Russia for a launch in 2024 would be “the most rapid and easiest way” to get to Mars, given that the rover and its landing platform are both already built. But “the way things are going with the war, it’s very difficult to think this may be possible.” Given the obstacles to such a partnership reemerging, Vago says the only real viable option is for ESA to build its own lander with NASA’s assistance. “This takes time,” he adds.

Time is not exactly on ESA’s side, however. The Earth-to-Mars voyage is easiest when both planets are properly aligned, which occurs every 26 months. The laborious process of building and testing new hardware would take a 2024 launch off the table, Vago says, but a 2026 or 2028 liftoff could be a possibility. ESA could potentially repurpose the parts it contributed to the Kazachok lander, yet the Russian-built components—the landing legs, heat shield, descent engines, and more—would have to be developed from scratch. The engines pose a particular problem because no European manufacturers offer any that are capable of landing on Mars. Similarly, ESA lacks the plutonium required for a radioisotope heating unit to keep the rover warm—something the U.S. (or Russia) could provide. “So we are asking NASA if they could contribute those,” Vago says. “These are the talks we’re having right now.”

ESA and NASA are already collaborating on the next steps for their joint Mars Sample Return program, with Europe assigned to develop the fetch rover to pick up the samples cached by Perseverance, as well as the spacecraft to bring those samples home. Vago says ESA might ask NASA to help out with ExoMars in return for ESA locking in its planned contributions to the sample-return effort. The situation carries considerable irony: In the early 2000s, Europe and the U.S. had tentative plans to work together on a life-seeking Mars mission, involving two rovers that would overlap in their science goals. But NASA pulled out of the endeavor in 2011, citing a lack of funding, before announcing the mission concept that would become the multi-billion-dollar Perseverance rover later that year. The other European-led component became the Franklin rover, and ESA was forced to turn to Russia as a partner. The experience left a bitter taste for many in Europe. “We were perplexed,” says Chris Lee, former chief space scientist at the U.K. Space Agency. “People were very annoyed.”

OXIA PLANUM OR BUST

The Franklin rover would touch down in a region of Mars’s northern hemisphere called Oxia Planum. This locale is home to another ancient river delta thought to date back 4.1 billion years—hundreds of millions of years older than the geologic features now being explored by Perseverance and Curiosity at their respective sites. If the rover is saved, it’s unlikely ESA would consider sending it to a different location. “We want to go to the site we have,” Vago says. “It’s amazing. It would be the oldest location that had been visited by a Mars mission. It gives us a unique chance to look at the very earliest minerals that were produced on Mars.”

The other uncomfortable possibility, however, is that ESA may cut its losses and choose to cancel the mission. Aside from developing a new landing system and purchasing a new rocket launch, storing the rover in perfectly clean conditions for six years would require a significant investment. Even now engineers must constantly flush the rover with argon to ensure it is kept in the pristine condition needed to minimize the chances of contamination from Earth-based microbes. Some experts wonder if those resources might be better spent elsewhere. “Is it worth it?” Lee says. “Unless the NASA discussions with ESA are all about trying to bring ExoMars back in from the cold, I really don’t see it going forward anymore.” But David Southwood, former director of science and robotic exploration at ESA, says the agency should do all it can to get the rover to Mars. “That would be my highest priority on a wish list,” he says.

What is certain is that the fate of this rover, troubled for so long, is likely to drag on for months. That leaves scientists working on the mission unsure of what their future holds. “If ExoMars is never going to be launched, this is a waste of our time and effort,” Ciarletti says. “For almost 20 years, we have been working on an instrument [for the rover]. It’s absolutely disappointing.” For now, European scientists eager to see their first homegrown rover reach Mars can do little more than wait. Quelle: SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

----

Update: 24.10.2022

.

Rosalind Franklin: Europe's delayed Mars rover to receive rescue package

Europe's research ministers are to be asked for "up to €360m" (£313.5m) to start the process of reconfiguring the Rosalind Franklin Mars rover mission.

The UK-built robot missed its window to go to the Red Planet this year when the West suspended all scientific co-operation with Russia.

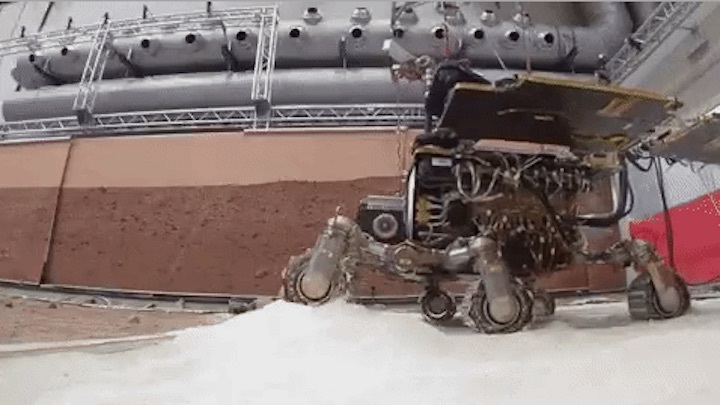

Engineers are now having to redesign the project to include only European and American components.

This shift in emphasis means the robot will not now launch until 2028.

A long cruise through space would result in a 2030 landing.

Eight years is a long time to wait, but European Space Agency (Esa) officials are convinced the scientific imperative behind the mission will still be compelling at the end of the decade.

"The point is there is no other mission that is foreseen or planned to actually go to a location on Mars that is four billion years old, and drill below the surface to look for prebiotic chemistry," Dr David Parker, Esa's head of human and robotic exploration, told BBC News.

The future of Rosalind Franklin was put in doubt when Russia invaded Ukraine.

The diplomatic fallout resulted in the suspension of the mission because it planned to not only use a Russian rocket to get off Earth, but also a Russian landing mechanism to get down to the surface of Mars. Western sanctions made such a joint undertaking impossible.

Officials have since been talking to their US counterparts about a transatlantic tie-up.

This would see the American space agency (Nasa) launch the rover, with European industry then taking on the responsibility for building the entry, descent and landing mechanism.

Nasa's interest would be served by ensuring Rosalind Franklin's key instrument reaches Mars. This chemistry lab, called the Mars Organic Molecule Analyser, was part-developed at the Goddard Space Flight Center in the US State of Maryland.

At its Esa's regular council meeting on Thursday, member-state delegations were presented with the rationale for continuing with the mission. The showcase was reportedly greeted at its conclusion with an enthusiastic round of applause.

The next step is for European research ministers to approve a budget for the reconfiguration. They will have an opportunity to do this in a few weeks when they gather in Paris to set Esa's near-term programmatic goals.

The €360m request will initiate the design work on the landing mechanism, although it should be stated that some of this money also covers the ongoing costs of Europe's Trace Gas Orbiter. This satellite, which is already at Mars, is supposed to be the communications relay for Rosalind Franklin when it finally arrives.

The rover itself will need some modifications. Principal among these is the removal of two Russian scientific instruments on board, and the installation of American radioisotope heaters to keep the robot warm in the freezing environment of the Red Planet.

In addition, engineers are thinking of making some upgrades. One of these could be a shake mode that would enable Rosalind Franklin to periodically rid itself of the Martian dust that over time would gather on its solar panels and reduce their efficiency.

Dr Parker said next month's budget request would not be sufficient to get the rover to the launch pad in 2028, and that further development funds would be required later in the decade.

Rosalind Franklin was assembled in an ultra-clean facility at the Stevenage, UK, factory of aerospace manufacturer Airbus. The company is hopeful the rover modifications can also be carried out in Britain.

The rover and the Trace Gas Orbiter, collectively referred to as the ExoMars project, have so far cost Esa member states well in excess of €1bn. The UK alone has invested more than €300m, with most of this money geared to the production of the wheeled robot.

Quelle: BBC