The 49ers who panned for gold during California’s Gold Rush didn’t really know where they might strike it rich. They had word of mouth and not much else to go on.

Researchers at the University of Central Florida want to give prospectors looking to mine the moon better odds of striking gold, which on the moon means rich deposits of water ice that can be turned into resources, like fuel, for space missions.

A team lead by planetary scientist Kevin Cannon created an Ice Favorability Index. The geological model explains the process for ice formation at the poles of the moon, and mapped the terrain, which includes craters that may hold ice deposits. The model, which has been published in the peer-reviewed journal Icarus, accounts for what asteroid impacts on the surface of the moon may do to deposits of ice found meters beneath the surface.

“Despite being our closest neighbor, we still don’t know a lot about water on the moon, especially how much there is beneath the surface,” Cannon says. “It’s important for us to consider the geologic processes that have gone on to better understand where we may find ice deposits and how to best get to them with the least amount of risk.”

The team was inspired by mining companies on Earth, which conduct detailed geological work, and take core samples before investing in costly extraction sites. Mining companies conduct field mappings, take core samples from the potential site and try to understand the geological reasons behind the formation of the particular mineral they are looking for in an area of interest. In essence they create a model for what a mining zone might look like before deciding to plunk down money to drill.

The team at UCF followed the same approach using data collected about the moon over the years and ran simulations in the lab. While they couldn’t collect core samples, they had data from satellite observations and from the first trip to the moon.

Why Mine the Moon

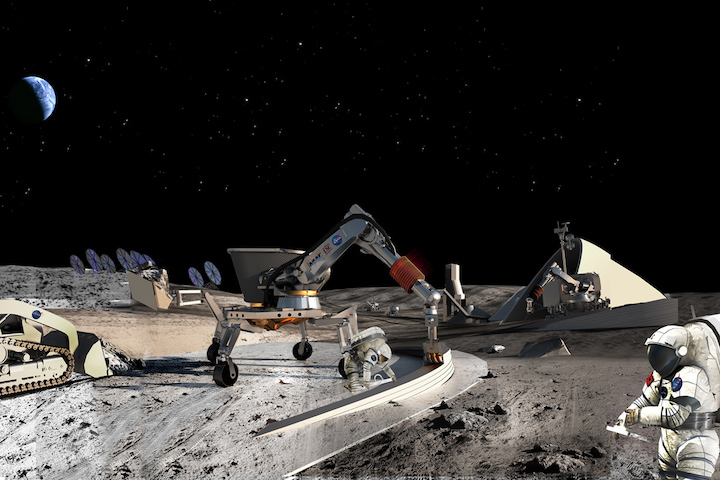

In order for humans to explore the solar system and beyond, spacecraft have to be able to launch and continue on their long missions. One of the challenges is fuel. There are no gas stations in space, which means spacecraft have to carry extra fuel with them for long missions and that fuel weighs a lot. Mining the moon could result in creating fuel , which would help ease the cost of flights since spacecraft wouldn’t have to haul the extra fuel.

Water ice can be purified and processed to produce both hydrogen and oxygen for propellent, according to several previously published studies. Sometime in the future, this process could be completed on the moon effectively producing a gas station for spacecraft. Asteroids may also provide similar resources for fuel.

Some believe a system of these “gas stations” would be the start of the industrialization of space.

Several private companies are exploring mining techniques to employ on the moon. Both Luxembourg and the United States have adopted legislation giving citizens and corporations ownership rights over resources mined in space, including the moon, according to the study.

“The idea of mining the moon and asteroids isn’t science fiction anymore,” says UCF physics Professor and co-author Dan Britt. “There are teams around the world looking to find ways to make this happen and our work will help get us closer to making the idea a reality.”

The study was supported by NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute cooperative agreement with the Center for Lunar and Asteroid Surface Science (CLASS) based at UCF.

This is not the first time Cannon nor UCF has contributed to the study of the soil of other planets. In 2018 they launched the Exolith Lab, which produces experimental Martian, Lunar and asteroid dirt for research and testing.

Cannon joined UCF in 2017. He has several degrees including a doctorate in planetary geology from Brown University. He has published more than 10 peer-reviewed papers and is a frequent guest speaker at universities nationwide because of his work in the composition of small bodies and Mars, and in in-situ resource utilization, and aqueous alteration.

Quelle: University of Central Florida