31.10.2019

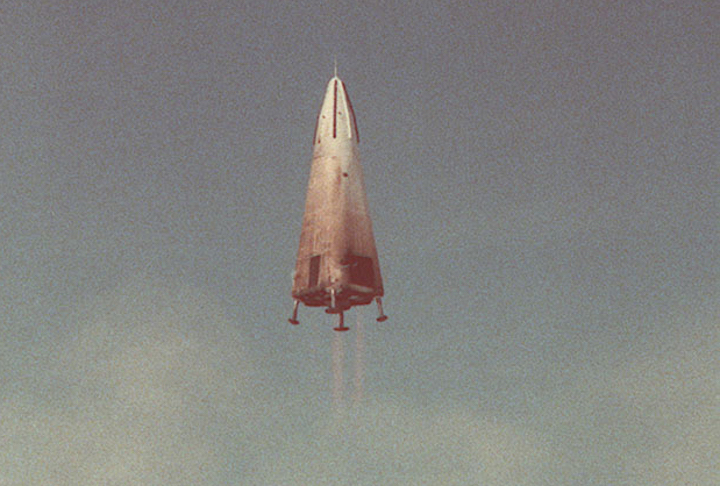

The rocket looked like it was out of a science fiction movie. A gleaming white pyramid resting on four spindly legs, the experimental craft was NASA’s ticket into a new era of space exploration.

With a series of built-in rockets on its underside, the ship could rise from the ground and touch back down again vertically — the first of its kind.

The Delta Clipper Experimental, or DC-X, could have formed the basis for a new generation of spacecraft. Indeed, a string of successful tests in the desert during the mid-1990s bore that promise out, hinting at future missions to low-Earth orbit and even the moon.

Today, spaceflight companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin are flying rockets based on the same vertical launch and landing concept that DC-X pioneered. The ability to reuse rockets in this way, rather than have them crash into the ocean, promises to bring costs down exponentially.

But almost 25 years ago, that dream of reusable spacecraft seemed quite far away. The DC-X, NASA’s futuristic spacecraft, ended its life in a fiery explosion on the launchpad.

Spacecraft for the Future

The DC-X was born in an era focused on space exploration. NASA’s space shuttle program had made dozens of successful flights to orbit, helping to bring legacy projects like the International Space Station and Hubble Space Telescope to life.

But there were drawbacks to the shuttles as well. Seven crew members died in 1986 when a gasket on the space shuttle Challenger failed. The shuttles also weren’t as reusable as expected.

Looking for a more sustainable option, DC-X began as a U.S. Air Force project with aerospace manufacturer McDonnell Douglas.

Until that time, no spacecraft could lift off with built-in rockets and then land vertically. The new rocket was testing never-before-seen technologies for spacecraft, and engineers saw it as an exciting project to be involved with.

“I look back on that time in my career, and I really appreciate it,” says Dan Dumbacher, the eventual project manager for the DC-X program. “We were doing things in the launch vehicles world that weren’t typically allowed.”

Rocket Tests

Construction started on the first DC-X prototype in 1991, and engineers began testing at the remote White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico on Aug. 18, 1993. For its maiden flight, the craft flew for just under a minute, reaching an altitude of 151 feet. In successive tests, the rocket continued to take off and land almost directly where it began the flight, delivering on the promise of reusability.

Plans to use the spacecraft for regular space travel were mentioned in long-term NASA plans. The agency said the rocket could offer a new, low-cost path to space. And, by one estimation, the price to fly on the spaceship would only be as much as a world trip on the Queen Elizabeth 2 ocean liner.

As the program matured, a new and upgraded version of the rocket, called DC-XA, began testing at White Sands. In 1996, the rocket flew three times, reaching a height of 10,000 feet during one test.