31.10.2019

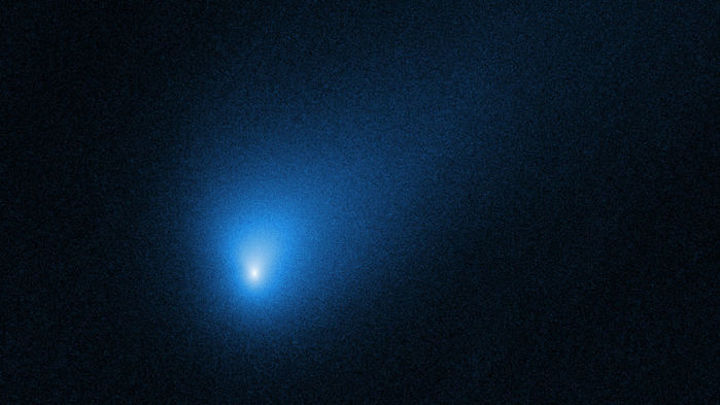

2I/Borisov, seen by the Hubble telescope, has brightened as it approaches the Sun.

NASA/ESA/D. JEWITT (UCLA)

The comet is an alien intruder from another star system. But 2I/Borisov, the second known interstellar visitor after far smaller ‘Oumuamua, discovered in 2017, looks remarkably like a normal comet from our own Solar System: an object a few kilometers across spewing carbon monoxide gas, water vapor, and dust. Researchers who announced their analysis this week say the size of the two objects, along with the rate of their discovery and other factors, suggests that at any given moment more than a dozen interstellar visitors at least as large as ‘Oumuamua are passing through the Solar System.

“Our current telescopes are not powerful enough to detect all of these objects,” says Bryce Bolin, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and lead author of the new study. But in the future, he says, large telescopes will be able to catch these visitors more often, perhaps two or three times a year.

The study is the most comprehensive look yet at an object that captured astronomers’ attention from the start. In the wee hours of 30 August, Gennady Borisov, an amateur astronomer in Crimea, was peering through a 65-centimeter telescope that he built himself when he spotted the first hints of what would become his namesake. Within weeks, astronomers had confirmed that Borisov was moving so fast, and on such an odd trajectory, that it must have originated from a distant star system.

Now, just 2 months later, a team of 43 astronomers from 26 institutions in eight countries has prepared a detailed study to submit to the American Astronomical Society for publication. While cigar-shaped ‘Oumuamua lacked a bright halo or tail and was discovered only after it was on its way out of the Solar System, Borisov is brighter and more active. The team says the new comet’s nucleus is at most 2 to 3 kilometers across—less than preliminary estimates of up to 10 kilometers but still an order of magnitude larger than ‘Oumuamua. Borisov, which is still inbound and will be easily visible at observatories around the world, will continue to brighten until it gets closest to the Sun on 7 December.

The study team experienced a similar growth in magnitude. It started small, at a planetary science conference in Geneva, Switzerland, in mid-September, where Borisov was the belle of the ball, Bolin says. “Everyone had their own theory about or plan on how to study this object.” He had been working to help refine the comet’s orbit and teamed up with Carey Lisse of Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, who had already begun to observe the comet using a 3.5-meter telescope at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico.

Bolin and Lisse then joined forces with GROWTH, an international consortium that specializes in tracking fast-changing astronomical events. The group ultimately included data from 10 observatories, including large telescopes in Hawaii, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), an all-sky survey based at the Palomar Observatory in California. Mining the ZTF’s archive, the researchers were able to identify images from as far back as March in which the object had appeared, unnoticed. “Effectively, we have about 7 months of observations of this comet,” Bolin says. The data revealed that, when the comet was still farther from the Sun than Jupiter, its surface was already releasing gas and dust, which would eventually form the bright tail.

Spectra of the comet at first suggested it had an overall reddish hue and was emitting cyanogen gas, which is also found in Solar System comets. The new study concludes that Borisov is a neutral gray and is also releasing plumes of carbon monoxide and water vapor, which account for the recent brightening.

In that respect, Borisov looks “remarkably like a normal Solar System comet,” says Colin Snodgrass, an astronomer at the University of Edinburgh who has seen the study. He’s impressed by how active it was early on—and how detectable it was so far away. If that behavior is typical for interstellar comets, he says, then the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, a giant telescope in Chile scheduled to come online in 2022, may find such objects even earlier in their approach.

That excites Snodgrass, who is the deputy principal investigator for the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) Comet Interceptor, which, after launch in 2028, will “park” itself in solar orbit between Earth and Mars and wait for a comet to study. The ESA team plans to intercept one of the pristine Solar System comets that, every year, make their first pass into the inner Solar System. Now, it appears that the mission could catch an alien comet as well, Snodgrass says. “This means that we may have a chance to actually see one up close.”

Quelle: AAAS