2.07.2019

NASA's InSight Uncovers the 'Mole'

Behold the "mole": The heat-sensing spike that NASA's InSight lander deployed on the Martian surface is now visible. Last week, the spacecraft's robotic arm successfully removed the support structure of the mole, which has been unable to dig, and placed it to the side. Getting the structure out of the way gives the mission team a view of the mole - and maybe a way to help it dig.

"We've completed the first step in our plan to save the mole," said Troy Hudson of a scientist and engineer with the InSight mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "We're not done yet. But for the moment, the entire team is elated because we're that much closer to getting the mole moving again."

Part of an instrument called the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3), the self-hammering mole is designed to dig down as much as 16 feet (5 meters) and take Mars' temperature. But the mole hasn't been able to dig deeper than about 12 inches (30 centimeters), so on Feb. 28, 2019 the team commanded the instrument to stop hammering so that they could determine a path forward.

Scientists and engineers have been conducting tests to save the mole at JPL, which leads the InSight mission, as well as at the German Aerospace Center (DLR), which provided HP3. Based on DLR testing, the soil may not provide the kind of friction the mole was designed for. Without friction to balance the recoil from the self-hammering motion, the mole would simply bounce in place rather than dig.

One sign of this unexpected soil type is apparent in images taken by a camera on the robotic arm: A small pit has formed around the mole as it's been hammering in place.

"The images coming back from Mars confirm what we've seen in our testing here on Earth," said HP3 Project Scientist Mattias Grott of DLR. "Our calculations were correct: This cohesive soil is compacting into walls as the mole hammers."

The team wants to press on the soil near this pit using a small scoop on the end of the robotic arm. The hope is that this might collapse the pit and provide the necessary friction for the mole to dig.

It's also still possible that the mole has hit a rock. While the mole is designed to push small rocks out of the way or deflect around them, larger ones will prevent the spike's forward progress. That's why the mission carefully selected a landing site that would likely have both fewer rocks in general and smaller ones near the surface.

The robotic arm's grapple isn't designed to lift the mole once it's out of its support structure, so it won't be able to relocate the mole if a rock is blocking it.

The team will be discussing what next steps to take based on careful analysis. Later this month, after releasing the arm's grapple from the support structure, they'll bring a camera in for some detailed images of the mole.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 31.08.2019

.

InSight mission seeking new ways to fix heat flow probe

WASHINGTON — Members of the InSight mission team are using a break in spacecraft operations to study new ways to get one of the spacecraft’s key instruments to resume burrowing into the Martian surface.

Scientists and engineers involved with InSight’s Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package instrument have been working for the last several months to get the instrument’s probe, or “mole,” to start moving into the surface again. The mole, intended to hammer to a depth of five meters below the surface, stopped in early March only about 30 centimeters below the surface.

In June, the mission decided to use the lander’s robotic arm to remove the support structure for the instrument. That would allow the instrument team to get a better view of the condition of the mole and also take new steps to get the mole moving again. Scientists believed that a lack of friction with the surrounding regolith was preventing the mole from gaining traction as it attempted to hammer deeper into the surface.

Removal of the support structure confirmed that hypothesis. Images showed the top of the mole peeking out above the surface in a hole about twice the diameter of the mole. A twist in the tether linking the mole to the rest of the instrument suggested it had started to spin around, widening the hole, as it tried to hammer deeper into the surface.

The instrument team then used InSight’s robotic arm again, pressing the scoop at the end of arm against the surface around the hole to try and collapse it. In an Aug. 27 blog post, Tilman Spohn, principal investigator for the instrument at the German space agency DLR, said that images taken after those attempts showed that the pit was only, at best, partially collapsed on one side.

Spohn said it appears there is a layer of “duricrust,” or regolith that is mechanically strong, on the surface, covered by about a centimeter of loose dust. Below that duricrust, which he estimated to be five to ten centimeters thick, could be “cohesionless sand” that prevents the mole from penetrating.

InSight is currently on hiatus while it and other spacecraft at Mars are in solar conjunction, with the sun between Mars and the Earth blocking communications. Spohn said that while the break is a time for some to take a vacation, he and others are thinking about new ways to get the mole moving again.

One possibility would be to use the scoop on the robotic arm in a different way. “I am thinking towards pinning the mole with the scoop such that the pinning and the pressing of the mole against the wall of the pit would increase friction,” he wrote. “This will be more risky than the previous strategy, but with the unexpectedly stiff duricrust, it may be worth a try.”

Spohn didn’t state when the mission would try a new approach to get the mole moving again. Andrew Good, a spokesman at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said Aug. 29 that there will be no action immediately after the solar conjunction period ends Sept. 7. It will take about a week after that to get all the data back from InSight and other spacecraft at Mars.

“Even after that, the team is continuing to conduct testing and discuss the next move,” he said, and thus there is no firm date for deciding what to do next with the mole.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 2.10.2019

.

NASA lander captures marsquakes, other Martian sounds

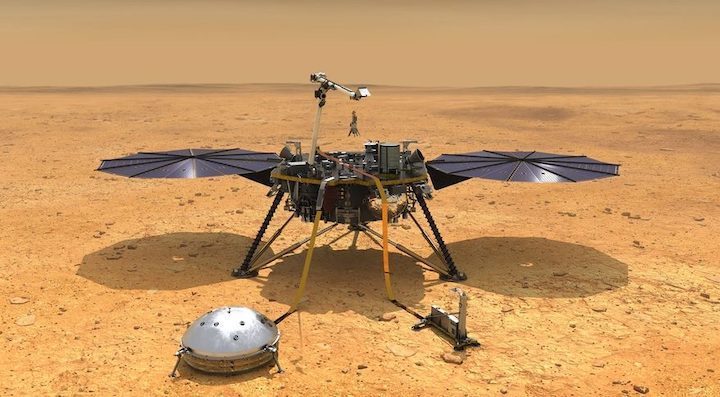

This April 25, 2019 photo made available by NASA shows the InSight lander's dome-covered seismometer, known as SEIS, on Mars. On Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019, scientists released an audio sampling of marsquakes and other sounds recorded by the probe.

NASA's InSight lander on Mars has captured the low rumble of marsquakes and a symphony of other otherworldly sounds.

Scientists released an audio sampling Tuesday. The sounds had to be enhanced for humans to hear.

InSight's seismometer has detected more than 100 events, but only 21 are considered strong marsquake candidates. The rest could be marsquakes — or something else. The French seismometer is so sensitive it can hear the Martian wind as well as movements by the lander's robot arm and other mechanical " dinks and donks " as the team calls them.

"It's been exciting, especially in the beginning, hearing the first vibrations from the lander," said Imperial College London's Constantinos Charalambous, who helped provide the audio recordings. "You're imagining what's really happening on Mars as InSight sits on the open landscape," he added in a statement.

InSight arrived at Mars last November and recorded its first seismic rumbling in April.

A German drilling instrument, meanwhile, has been inactive for months. Scientists are trying to salvage the experiment to measure the planet's internal temperature.

The so-called mole is meant to penetrate 16 feet (5 meters) beneath the Martian surface, but has managed barely 1 foot (30 centimeters). Researchers suspect the Martian sand isn't providing the necessary friction for digging, causing the mole to helplessly bounce around rather than burrow deeper, and to form a wide pit around itself.

Quelle: abcNews

+++

NASA's InSight 'Hears' Peculiar Sounds on Mars

-

Put an ear to the ground on Mars and you'll be rewarded with a symphony of sounds. Granted, you'll need superhuman hearing, but NASA's InSight lander comes equipped with a very special "ear."

The spacecraft's exquisitely sensitive seismometer, called the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS), can pick up vibrations as subtle as a breeze. The instrument was provided by the French space agency, Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES), and its partners.

SEIS was designed to listen for marsquakes. Scientists want to study how the seismic waves of these quakes move through the planet's interior, revealing the deep inner structure of Mars for the first time.

But after the seismometer was set down by InSight's robotic arm, Mars seemed shy. It didn't produce its first rumbling until this past April, and this first quake turned out to be an odd duck. It had a surprisingly high-frequency seismic signal compared to what the science team has heard since then. Out of more than 100 events detected to date, about 21 are strongly considered to be quakes. The remainder could be quakes as well, but the science team hasn't ruled out other causes.

Quakes

Put on headphones to listen to two of the more representative quakes SEIS has detected. These occurred on May 22, 2019 (the 173rd Martian day, or sol, of the mission) and July 25, 2019 (Sol 235). Far below the human range of hearing, these sonifications from SEIS had to be speeded up and slightly processed to be audible through headphones. Both were recorded by the "very broad band sensors" on SEIS, which are more sensitive at lower frequencies than its short period sensors.

The Sol 173 quake is about a magnitude 3.7; the Sol 235 quake is about a magnitude 3.3.

Each quake is a subtle rumble. The Sol 235 quake becomes particularly bass-heavy toward the end of the event. Both suggest that the Martian crust is like a mix of the Earth's crust and the Moon's. Cracks in Earth's crust seal over time as water fills them with new minerals. This enables sound waves to continue uninterrupted as they pass through old fractures. Drier crusts like the Moon's remain fractured after impacts, scattering sound waves for tens of minutes rather than allowing them to travel in a straight line. Mars, with its cratered surface, is slightly more Moon-like, with seismic waves ringing for a minute or so, whereas quakes on Earth can come and go in seconds.

Mechanical Sounds and Wind Gusts

SEIS has no trouble identifying quiet quakes, but its sensitive ear means scientists have lots of other noises to filter out. Over time, the team has learned to recognize the different sounds. And while some are trickier than others to spot, they all have made InSight's presence on Mars feel more real to those working with the spacecraft.

"It's been exciting, especially in the beginning, hearing the first vibrations from the lander," said Constantinos Charalambous, an InSight science team member at Imperial College London who works with the SP sensors. "You're imagining what's really happening on Mars as InSight sits on the open landscape."

Charalambous and Nobuaki Fuji of Institut de Physique du Globe de Parisprovided the audio samples for this story, including the one below, which is also best heard with headphones and captures the array of sounds they're hearing.

On March 6, 2019, a camera on InSight's robotic arm was scanning the surface in front of the lander. Each movement of the arm produces what to SEIS is a piercing noise.

Wind gusts can also create noise. The team is always on the hunt for quakes, but they've found the twilight hours are one of the best times to do so. During the day, sunlight warms the air and creates more wind interference than at night.

Evening is also when peculiar sounds that the InSight team has nicknamed "dinks and donks" become more prevalent. The team knows they're coming from delicate parts within the seismometer expanding and contracting against one another and thinks heat loss may be the factor, similar to how a car engine "ticks" after it's turned off and begins cooling.

You can hear a number of these dinks and donks in this next set of sounds, recorded just after sundown on July 16, 2019 (Sol 226). Listen carefully and you can also pick out an eerie whistling that the team thinks may be caused by interference in the seismometer's electronics.

What does it sound like to you? A hall full of grandfather clocks? A Martian jazz ensemble? Share your thoughts with us on Twitter.

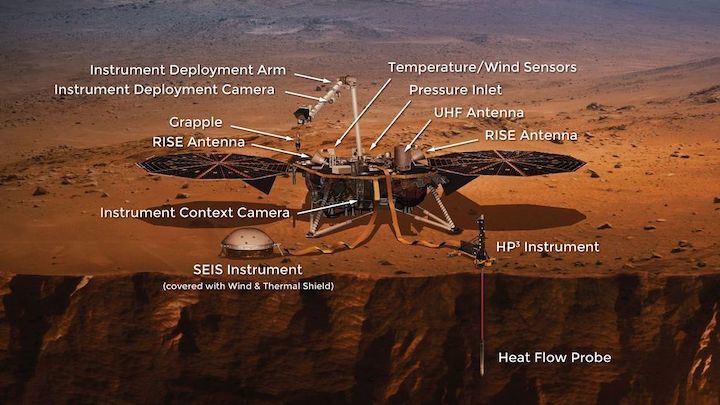

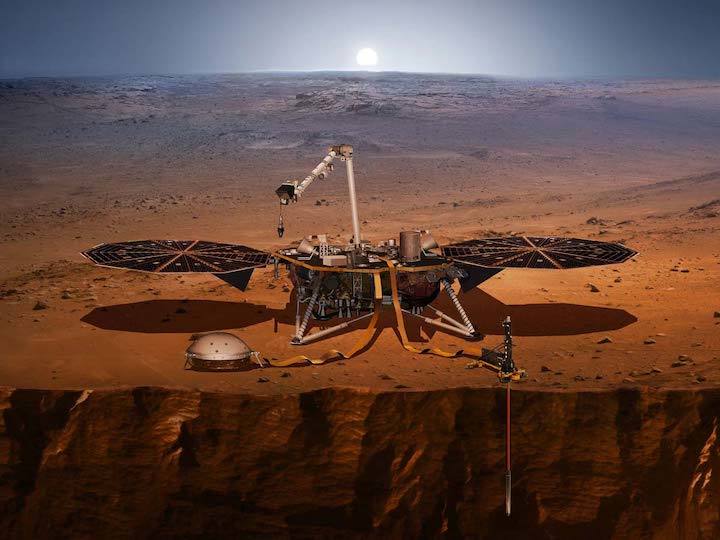

About InSight

JPL manages InSight for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA's Discovery Program, managed by the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the mission.

A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument to NASA, with the principal investigator at IPGP (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris). Significant contributions for SEIS came from IPGP; the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany; the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) in Switzerland; Imperial College London and Oxford University in the United Kingdom; and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain's Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the temperature and wind sensors.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 7.10.2019

.

NASA's scheme to resurrect the drill on its Mars probe

The InSight lander's "self-hammering heat probe" stuck in the Martian soil.

NASA blasted the InSight lander to Mars with the aim of drilling some 16 feet into the Martian ground.

But the drill, also called the "mole" or "self-hammering heat probe," only burrowed 14 inches into the soil before getting stuck. The space agency hasn't been able to move the heat-detecting probe since February.

But NASA has a plan. And the people behind that plan appear confident.

"This is a very, very challenging problem," said Ashitey Trebi-Ollennu, the lead arm engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Sometimes it appears intractable. But we engineers love solving challenging problems."

The strategy is relatively simple in theory, but of profound difficulty to deploy from tens of millions of miles away.

NASA engineers plan to use a robotic scoop to scrape red soil into the 14-inch hole and fill it up. Then, they'll plant the flat bottom of the metal scoop into the soil next to mole, thus pinning the drill against the scoop.

This way, the drill won't bounce around as much in the hole. Instead, the drill's hammering motion will be forced down into what NASA believes is highly compact or clumped soil. (Though, it may also be a rock, which could doom this part of InSight's mission.)

"This might increase friction enough to keep it moving forward when mole hammering resumes," Sue Smrekar," the InSight Deputy Principal Investigator, said in a statement.

Previously, NASA used the scoop to push on the soil around the hole, hoping to collapse the hole so the drill wouldn't wobble around. But NASA failed to collapse the shallow pit.

Ultimately, the goal is to drill 16 feet into the Martian ground where the probe can measure the heat inside Mars' interior. How geologically active is the planet, and what exactly is going on below the desert surface, are two weighty questions.

"We're cautiously optimistic that one day we'll get the mole working again," Trebi-Ollennu said.

Quelle: Mashable

----

Update: 19.10.2019

.

Mars lander's digger is burrowing again after snag

This October 2019 photo made available by NASA shows InSight's heat probe digging into the surface of Mars. On Thursday, Oct. 17, 2019, NASA says the drilling device has penetrated three-quarters of an inch (2 centimeters) over the past week, after hitting a snag seven months ago. While just a baby step, scientists are thrilled with the progress.

A Mars lander's digger is burrowing into the red planet again after hitting a snag seven months ago.

NASA said Thursday the mechanical mole has penetrated three-quarters of an inch (2 centimeters) over the past week. While just a baby step, scientists are thrilled with the progress.

"We're rooting for our mole to keep going," said the experiment's lead scientist, Tilman Spohn of the German Aerospace Center, in a statement.

The German device is meant to penetrate 16 feet (5 meters) into Mars to measure internal temperatures. It barely got a foot down (30 centimeters) before stalling in March, soon after starting to hammer. Over the weeks and months, engineers devised a backup plan: To help, the robot arm on the InSight lander is pressing against the drill to create enough friction for it to keep digging.

Since Oct. 8, the mole has hammered 220 times on three occasions, making slow but steady progress.

Scientists said it will take time — and lots more hammering — to see how deep it goes.

"When we first encountered this problem, it was crushing," said the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Troy Hudson, who is leading the recovery effort.

"But I thought, 'Maybe there's a chance; let's keep pressing on.' And right now, I'm feeling giddy," he said in a statement.

InSight arrived at Mars last November.

Quelle: abcNews

----

Update: 28.10.2019

.

InSight heat flow probe suffers setback

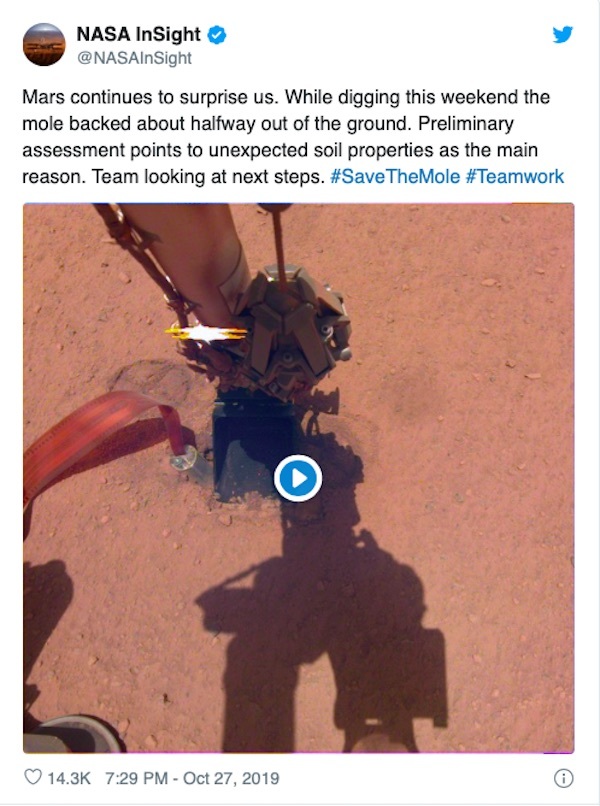

WASHINGTON — A heat flow instrument on NASA’s InSight Mars lander suffered a setback Oct. 26 in its efforts to penetrate into the Martian surface.

Images returned late Oct. 26 by the lander showed that the probe, or mole, emerging from a hole onto the surface. The most recent images show most of the mole now above ground.

The mole has an internal hammer that was designed to make thousands of strokes, slowly pushing it deeper into the surface. The mole became stuck early this year, though, after penetrating only about 30 centimeters below the surface, far short of its goal of five meters.

Engineers spent months developing plans to try to get the mole moving again. Earlier this month, they reported success with using the scoop on the end of the lander’s robotic arm to pin the mole to one side of the hole, increasing its friction and allowing the mole to move deeper into the surface.

That progress continued in recent days even after moving the arm so that it was no longer pinning the mole. “The images that we got down on 23 and 24 October clearly show that the Mole had digged further!” wrote Tilman Spohn, principal investigator for the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package instrument at the German space agency DLR, in an Oct. 25 blog post. The mole, he added, appeared to be penetrating into the surface at a slightly faster rate than when it was pinned by the arm.

In that blog post, Spohn said his team had commanded the mole to perform two sets of 150 strokes of its hammer on sol, or Martian day, 326 for the mission. “We will then increase the number of strokes per sol and hope to see it disappear from our view into the Martian regolith soon,” he wrote.

But images returned after that hammering showed that the mole had bounced mostly out of the hole. “While digging this weekend the mole backed about halfway out of the ground,” the mission announced via a pair of tweets Oct. 27. “Preliminary assessment points to unexpected soil properties as the main reason.”

The mission added that one possibility is soil is falling in front of the mole, filling the hole. “Team continues to look over the data and will have a plan in the next few days.”

“We’re analyzing the problem and will share what we have tonight and provide more detailed information tomorrow after engineers have analyzed the data,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, said in a separate series of tweets Oct. 27.

He added that despite the problem with the mole, the mission is “functioning very well” overall and that the mole was not a “so-called Level 1 [requirement] for mission success.” However, the overall instrument is one of two major payloads on the mission, along with a seismometer that is working normally.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 30.10.2019

.

Ground teams studying setback with InSight’s subsurface heat probe

The self-hammering mole on NASA’s InSight lander partially backed out of the ground over the weekend, the latest setback for a German-built science instrument designed to measure heat flowing from the interior of Mars.

“After making progress over the past several weeks digging into the surface of Mars, InSight’s mole has backed about halfway out of its hole this past weekend,” officials from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory wrote in a statement Sunday. “Preliminary assessments point to unusual soil conditions on the Red Planet. The international mission team is developing the next steps to get it buried again.”

“It was a big disappointment to get those images down,” said Bruce Banerdt, InSight’s principal investigator at JPL. “Everybody on the Internet saw them the same time we did because they go out to the Web server as soon as we get them down.”

The heat probe has encountered difficulty digging into the Martian soil, and ground teams earlier this year decided to use the InSight lander’s robotic arm to assist the stalled mole.

The Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package, or HP3 instrument, has been unable to dig into Mars since Feb. 28. The device stalled within minutes after beginning to burrow to a planned depth of 16 feet (5 meters) beneath the Martian surface, deeper than any probe has dug into the Red Planet’s crust.

The robotic arm removed a surface support structure covering the heat probe instrument in June, allowing ground teams to assess the mole’s condition. They found a pit had formed around the circumference of the mole, suggesting the Martian soil was not providing enough friction, or resistance, as the self-hammering probe attempted to drive itself into the ground.

Beginning earlier this month, ground controllers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California commanded the lander’s robotic arm to assist the 1.3-foot (40-centimeter) mole. Teams were using the arm’s scoop to pin the mole against one side of the hole in a bid to apply extra pressure to compensate for the soil at InSight’s landing site, which appears to clump together rather than loosely fall around the mole as it hammers.

Inspections using InSight’s robot arm camera indicated the presence of 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 centimeters) of duricrust, a type of cemented soil thicker than anything encountered on other Mars missions, according to JPL. The duricrust is also different from the soil the mole was designed for.

The unique soil properties have caused the mole to bounce in place as it recoils from each stroke of its built in hammer mechanism, rather than dig deeper as designed.

“A scoop on the end of the arm has been used in recent weeks to ‘pin’ the mole against the wall of its hole, providing friction it needs to dig,” JPL said in a statement. “The next step is determining how safe it is to move InSight’s robotic arm away from the mole to better assess the situation. The team continues to look at the data and will formulate a plan in the next few days.”

The new technique of using the robot arm to pin the mole against the side of the hole produced promising results before last weekend’s setback.

JPL reported Oct. 17 that the mole had dug about three-quarters of an inch (2 centimeters) since the robotic arm started assisting, the first measurable progress in more than seven months.

Developed by DLR, the German space agency, the HP3 instrument includes the metallic mole and a ribbon-like tether trailing behind it, through the surface support structure, and back to the InSight lander. The umbilical routes power to the instrument, and allows data from temperature sensors on the mole and tether to flow back to the lander for transmission back to Earth.

Mission managers never intended to use InSight’s robotic arm to assist the mole or move the instrument’s support structure, and engineers have carefully planned maneuvers with the arm to reduce the risk of damaging the mole’s sensitive tether umbilical.

Scientists said earlier this year that the HP3 instrument could not be recovered if the mole comes out of its hole.

The HP3 mole’s partial withdrawal from the clumpy Martian soil may leave ground teams with some hope of saving the instrument.

“We convened a meeting the next morning, and right away, the way NASA engineers do, they started saying, ‘What we can do about this? How can we fix this?'” Banerdt said Tuesday. “So we already have ideas on how to try and recover from this. We might not be able do, but we have some great ideas and we have an amazing team behind this experiment, and behind this mission, and we’ve gotten great support from NASA and from the German space agency, DLR.

“So we’re going to give it another shot and see whether we can pull this thing back together and get it back down into the ground,” Banerdt said in a conversation with Thomas Zurbuchen, head of NASA’s science division, at JPL Tuesday.

Zurbuchen tweeted Sunday that the mole is not required for the $1 billion InSight mission to achieve its minimum criteria for success.

The heat flow measurements intended to be collected by the HP3 instrument are part of InSight’s so-called “Level 1” requirements, but were listed as a stretch goal, not as a requirement for minimum mission success, according to Banerdt.

“NASA funds our mission and supports us, and in return, we sort of promise a certain number of scientific measurements and results,” Banerdt said. “We have about 10 of those for InSight. We call them our Level 1 requirements, and one of those Level 1 requirements is for a measurement of the heat flow of Mars using our HP3.

“In the official NASA hierarchy we have two sets of Level 1 requirements,” Banerdt said. “We have the threshold, which is the things that we need to do in order just to make mission success. So if we get these six (of 10 Level 1 requirements), then we consider the mission to be successful. Those are what were judged by a scientific blue ribbon panel to be enough to justify the expense and the trouble of sending this mission to Mars.”

The heat flow measurements are part of four additional Level 1 requirements for InSight.

“These four additional ones are extra science that we really want to get done — it’s really great science — but either we thought that it was a little bit riskier, or some of them maybe aren’t quite as important as the other ones, so they’re considered nice to have,” Banerdt said.

Zurbuchen said differentiating between threshold Level 1 requirements and the four additional “baseline” requirements allows mission planners to take risks.

“We want to take risks,” he said. “So we do not want the baseline and the thresholds to be one and the same because we want to create that space for experimentation.”

HP3 is one of two geophysics instruments on the InSight lander, which arrived at Mars last November.

A French-built seismometer is working as expected and has already detected multiple marsquakes for the first time.

A third major science investigation on the InSight mission is the Rotation and Interior Structure Experiment, or RISE, which uses radio signals passed between the lander and Earth to measure the wobble of Mars’s rotation, giving scientists an idea of the Red Planet’s core size and density.

Quelle: SN