23.08.2018

The Milky Way galaxy has died once before and we are now in what is considered its second life. Calculations by Masafumi Noguchi (Tohoku University) have revealed previously unknown details about the Milky Way. These were published in the July 26 edition of Nature.

Stars formed in two different epochs through different mechanisms. There was a long dormant period in between, when star formation ceased. Our home galaxy has turned out to have a more dramatic history than was originally thought.

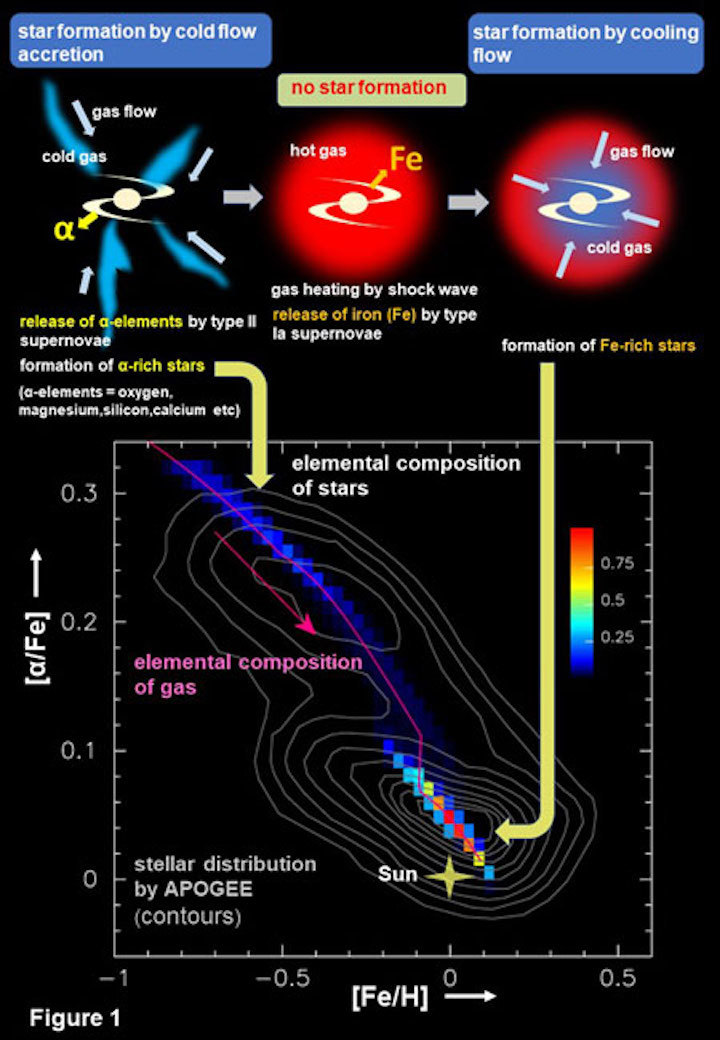

Schematic diagram showing two stages of star formation in the Milky Way galaxy according to Noguchi. In upper illustration, blue (cold) and red (hot) indicate gas. The color map in bottom panel shows distribution of the elemental composition of stars calculated by Noguchi's model with the purple line indicating how the elemental composition of the gas changes over time (Credit: M. Noguchi, courtesy of Nature). Overlaid contours show the distribution of solar neighborhood stars observed by APOGEE, a spectroscopic device attached to the 2.5 m telescope of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico (Credit: M. Haywood et al. A&A, 589, 66 (2016), reproduced with permission © ESO).

-

Noguchi has calculated the evolution of the Milky Way over a 10 billion year period, including "cold flow accretion", a new idea proposed by Avishai Dekel (The Hebrew University) and colleagues for how galaxies collect surrounding gas during their formation. Although the two-stage formation was suggested for much more massive galaxies by Yuval Birnboim (The Hebrew University) and colleagues, Noguchi has been able to confirm that the same picture applies to our own Milky Way.

The history of the Milky Way is inscribed in the elemental composition of stars because stars inherit the composition of the gas from which they are formed. Namely, stars memorize the element abundance in gas at the time they are formed.

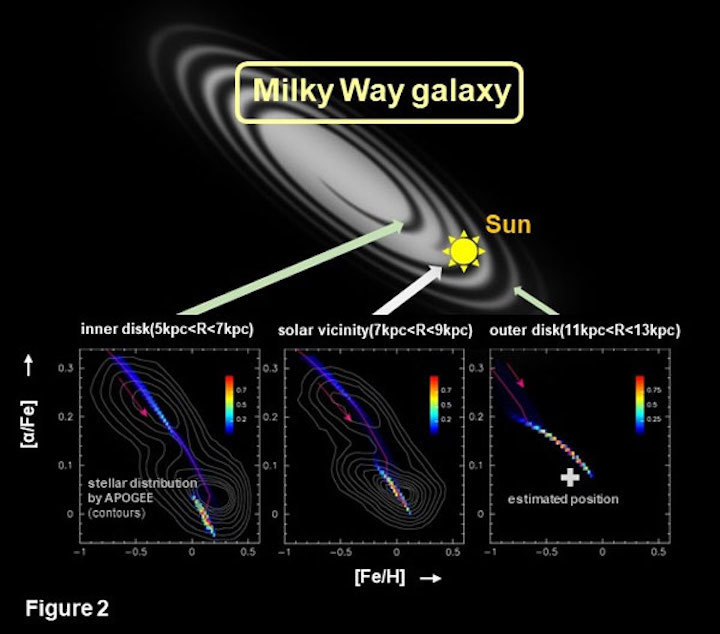

There are two groups of stars in the solar neighborhood with different compositions. One is rich in α-elements such as oxygen, magnesium and silicon. The other contains a lot of iron. Recent observations by Misha Haywood (Observatoire de Paris) and colleagues revealed that this phenomenon prevails over a vast region of the Milky Way. The origin of this dichotomy was unclear. Noguchi's model provides an answer to this long-standing riddle.

Noguchi's depiction of the Milky Way's history begins at the point when cold gas streams flowed into the galaxy (cold flow accretion) and stars formed from this gas. During this period the gas quickly began to contain α-elements released by explosions of short-lived type II supernovae. These first generation stars are therefore rich in α-elements.

When shock waves appeared and heated the gas to high temperatures 7 billion years ago, the gas stopped flowing into the galaxy and stars ceased to form. During this period, retarded explosions of long-lived type Ia supernovae injected iron into the gas and changed the elemental composition of the gas. As the gas cooled by emitting radiation, it began flowing back into the galaxy 5 billion years ago (cooling flow) and made the second generation of stars rich in iron, including our sun.

Model prediction for three different regions of the Milky Way (Credit: M. Noguchi, courtesy of Nature). Contours are from observations by APOGEE (Credit: M. Haywood et al. A&A, 589, 66 (2016), reproduced with permission © ESO).

-

According to Benjamin Williams (University of Washington) and colleagues, our neighbor galaxy, Andromeda nebula, also formed stars in two separate epochs. Noguchi's model predicts that massive spiral galaxies like the Milky Way and Andromeda nebula experienced a gap in star formation, whereas smaller galaxies made stars continuously. Noguchi expects that "future observations of nearby galaxies may revolutionize our view about galaxy formation."

Quelle: Astronomical Institute, Tohoku University