29.12.2017

President Donald Trump’s National Security Strategy set a new course by focusing on rebuilding the domestic economy as central to national security and its aim at “rival powers, Russia and China, that seek to challenge America influence, values, and wealth.” Critics observed that the White House seemed to reverse past presidents’ emphasis on advancing democracy and liberal values, reject both reducing global warming and spreading free trade as national security goals, and elevating American sovereignty over international cooperation.

Less noticed but perhaps equally revisionist, the National Security Strategy reverses the Obama administration’s lead-from-behind approach to outer space. As American military and civilian networks have increased their dependence on satellite networks, the Obama White House deferred to European efforts to develop a “Code of Conduct” that would reduce the chances of armed conflict in space.

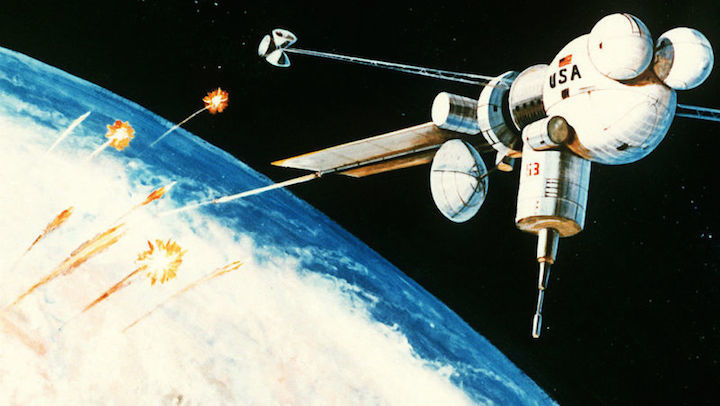

Rejecting these treaties and vague international norms, the Trump administration instead relies on unilateralism: “any harmful interference with or an attack upon critical components of our space architecture that directly affects this vital U.S. interest will be met with a deliberate response at a time, place, manner, and domain of our choosing.”

Trump has the central issue right: control of space underlies the United States’s predominant position in world affairs. Communications satellites provide the high-speed data transfer that stitches the U.S. Armed Forces together, from generals issuing commands to pilots controlling drones. Other satellites monitor rival nations for missile launches, strategic deployments, or troop movements. America’s nuclear deterrent itself uses space: land- or sea-based ballistic missiles leave and then reenter the atmosphere, giving them a global reach that is difficult to defend against.

The global positioning system (GPS) allows U.S. aircraft, naval vessels, and ground units to locate their whereabouts and to direct their fire with precision. The stunning speed of the initial invasion of Iraq in 2003, like the earlier triumph of the Persian Gulf War in 1991, demonstrates the lethal success of military operations that integrate satellite communications and information gathering. The drone campaign against terrorist leaders in the Middle East and Pakistan depends on satellites to locate targets, conduct real-time surveillance, and then control the fire systems of the drones.

The future holds even more advances in store. Building on precision-guided munitions, the U.S. Defense Department is developing a “prompt global strike” system that will use GPS satellites to guide hypersonic missiles, armed with conventional warheads, to targets anywhere in the world within an hour.

Civilian networks similarly depend on space. GPS has transformed the transportation industry. Navigation products allow for quicker driving for individual cars, more efficient cargo transport by trucks, rail, and ships, and fuel-saving routes for airplanes. Autonomous cars, ride-sharing, and delivery services similarly rely on GPS. Other satellites predict the weather, while yet others transmit communications and data.

Private industry has also begun to exploit the commercial potential of space. The space economy is now estimated to be a $330 billion global commercial enterprise, $251 billion of which is contributed by private commercial actors, with the rest of the revenue being generated by government spending.

The U.S. Defense Department relies on commercial satellites for about 40 percent of its communication needs. The idea of sending civilians into space is even beginning to take flight. Elon Musk’s SpaceX has developed rockets to transport cargo to the International Space Station, while Virgin Galactic is already selling seats for space tourism.

While space-based systems enhance military operations and civilian networks, they also expose vulnerabilities. Enemy destruction of U.S. reconnaissance satellites would blind its strategic monitoring and degrade its operational and tactical abilities. Anti-satellite attacks could even the technological odds against western powers that have developed information-enhanced operations. Chinese strategists discuss countering U.S. superiority in conventional and nuclear weapons with “soft kill” attacks on American satellites, which would blind American forces and interfere with U.S. communications and control.

While China has steadily advanced its manned space program, it has also developed the technologies necessary for anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons. In 2007, for example, China tested a ground-launched missile to destroy one of its own weather satellite in low-Earth orbit, in the same region inhabited by commercial satellites. “For countries that can never win a war with the United States by using the methods of tanks and planes, attacking an American space system may be an irresistible and most tempting choice,” a Chinese analyst wrote in a much-noticed comment.

The potential for space warfare has led to calls to ban the “militarization” of space. Such efforts began as early as the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which declares its purpose “to promote international co-operation in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space.” The Treaty forbids the stationing of nuclear weapons (and other WMD) in orbit and bans military installations or operations on the moon and other celestial bodies. The Treaty also forbids any nation from claiming sovereignty over the moon and planets or even the space above their territory (unlike airspace, for example).

Ever since, some have argued that space must be an arms-free zone, and any use of space for military purposes, even non-aggressive ones, violates international law. The United Nations General Assembly has repeatedly passed resolutions “to prevent an arms race in outer space.” The Obama administration gave into such hopes with its quiet support of the European space Code of Conduct, which sought to restrain arms competition in space.

While the Trump NSS is a document, but not an operating strategy, it shows that the administration is making the right moves in rejecting utopian visions of space as conflict-free zone. The great powers have already carefully crafted treaties to limit a nuclear arms race in outer space. But at the same time they have left open significant routes for other military uses of space. Current law, for example, does not prohibit the passage of weapons through space, such as ballistic missiles, the stationing of reconnaissance satellites, or the basing of conventional weapons in orbit. States can use force in these ways to achieve the same goals as with other high-tech weapons: for self-defense, to pursue terrorist groups, to stop international crises, and to resolve disputes between states.

While the Trump NSS recognizes the value of space, it sets no agenda for more effective use of the arena. It calls for more commercialization and exploration of space, but little else. The Trump administration should devote more resources to the development of space-based weapons, both to prevent ballistic missiles from rogue nations such as North Korea and Iran, and to defend against anti-satellite attacks from China and Russia.

Combat in space will raise the same questions as with other technologies, due to the integration of civilian and military networks in space. But it also realizes the same benefits: greater precision in attack, a reduction in battle casualties, and clearer signaling between great powers, which should help settle their controversies.

Nations can coordinate to place certain areas of space off limits to occupation, such as the moon or planets, rendering them akin to the legal status of Antarctica. But it would deny reality to expect the United States and its competitors to ignore the military and technological advantages made possible by space.

John Yoo is a professor at the UC Berkeley Law School and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author (with Jeremy Rabkin) of Striking Power: How Cyber, Robots, and Space Weapons Change the Rules for War (Encounter Books).

Quelle: The Hill