.

Engineers suspect a piece of foreign object debris may be intermittently stalling a motor needed to place the Curiosity Mars rover’s drill bit onto rocks, and the robot’s ground team is assessing the source of the potential contamination.

More importantly, Curiosity project manager Jim Erickson said, engineers are spending the holidays crunching data from a series of diagnostic tests conducted in recent weeks to analyze the drill’s behavior and determine a possible fix.

Curiosity is in its second extended mission — the rover’s original primary mission phase ended in 2014 — on the lower flank of Mount Sharp, a three-mile-high (5-kilometer) peak towering over the floor of Gale Crater, the robot’s landing site.

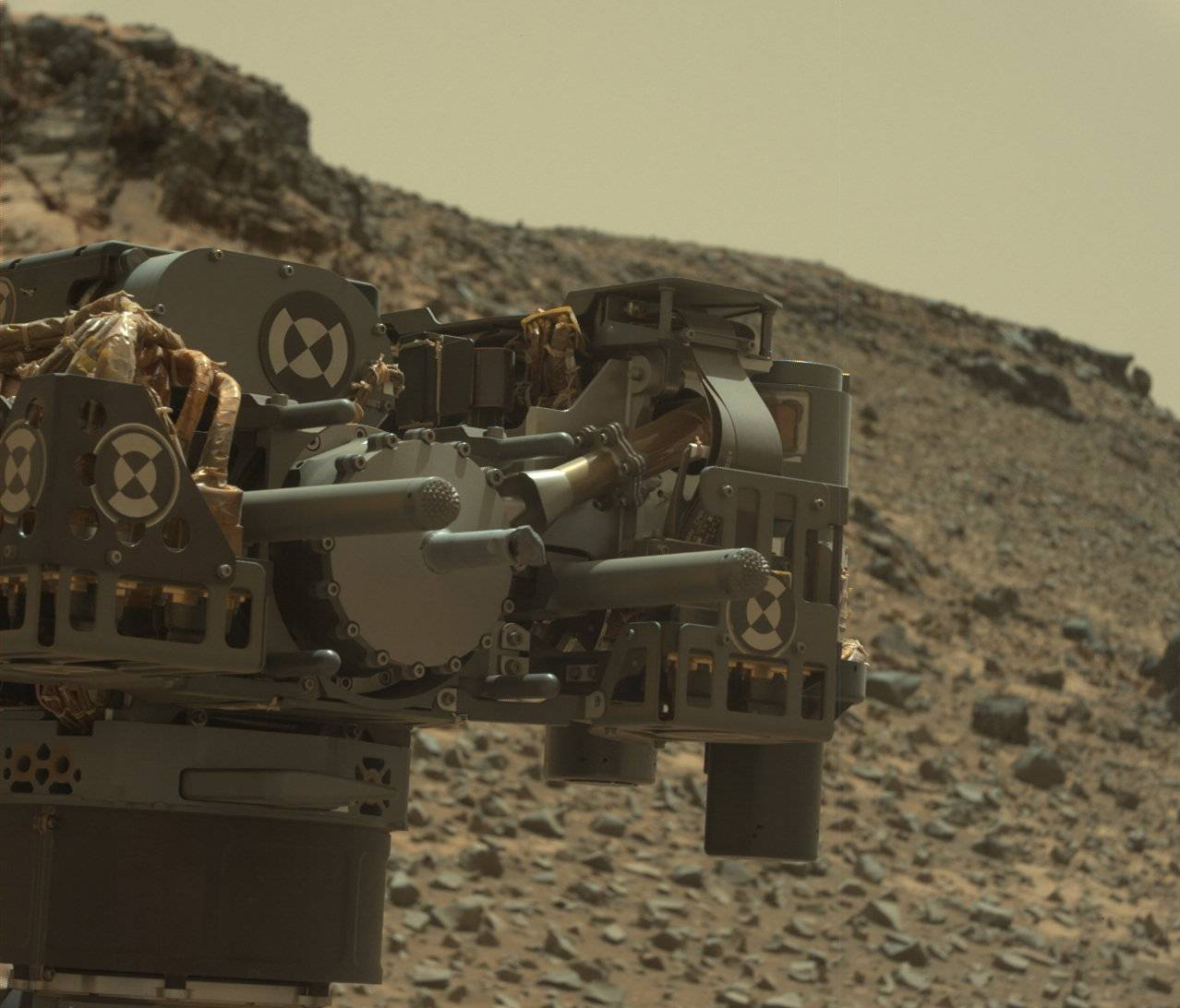

The rover’s drill pulverizes material from inside Martian rocks into powder, and delivers the samples to two of Curiosity’s main science instruments — the Sample Analysis at Mars payload and the Chemistry and Mineralogy package — to look for organic materials and measure mineral content.

Ground controllers believe the drill problem is rooted in a brake on the drill feed mechanism, which is supposed to extend and place the drill bit on the surface of target rocks.

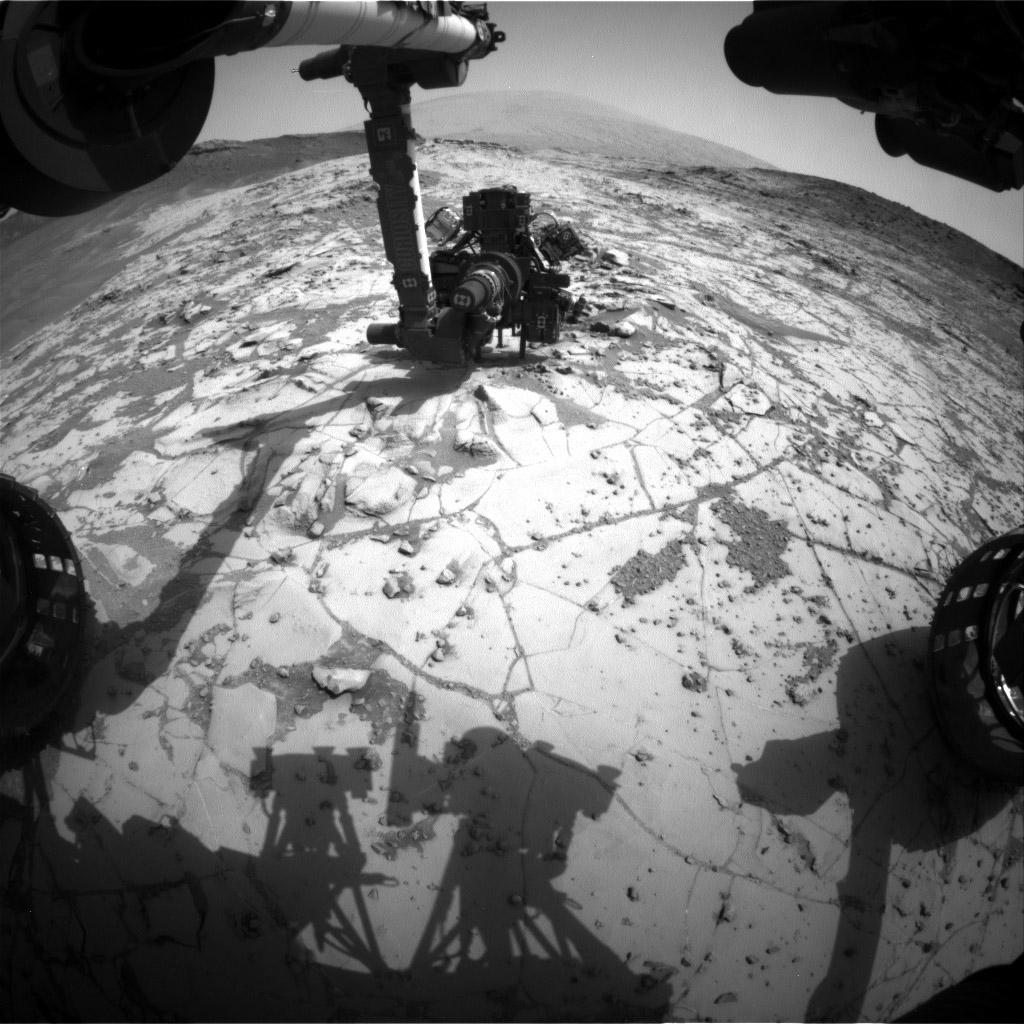

When Curiosity goes in to drill into Martian rocks, the rover extends its robotic arm and two prongs on each side of the drill bit press against the target. The drill feed motor then engages to push the bit onto the rock, then percussive and rotating mechanisms start boring into the target to collect a powder sample.

Erickson told Spaceflight Now that the drill problem, first encountered Dec. 1, has cropped up off and on, but ground controllers have only commanded the motor to move in tiny increments in their testing.

Rover drivers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, have also sent Curiosity on short trips and activated shakers inside the drill to test the feed motor’s response to motion, Erickson told Spaceflight Now in JPL’s “Mars yard” facility where engineers test out rover models in simulated Martian terrain.

The shakers are normally used to sort the powder sample acquired by the drill.

Experts believe they found a pattern in the way the drill feed motor behaves over time, Eriskson said, and the pattern observed so far matches what engineers would expect to see if a piece of foreign object debris, or FOD, was embedded somewhere inside the drill.

Erickson said the ground team is not sure of the source of the potential debris. It could be a piece of Martian soil or a pebble that somehow got into the mechanism and is gumming up the drill feed motor, or it might be something carried from Earth.

“It some sense, it probably doesn’t matter,” Erickson said, detailing how engineers are focused, for now, on recovering use of the drill, one of the rover’s primary tools.

He described a “fishbone” diagram used by the investigation team, with arrows splitting off pointing to FOD of terrestrial and Martian origin. Then there’s another split in the fishbone, Erickson said, illustrating two more possibilities, assuming the contamination came from Earth.

“Was it something that the rover carried from Earth from before the launch, or was it generated after the launch?” Erickson asked.

Parts inside the drill may have rubbed together over the last four years since Curiosity’s landing on Mars in August 2012, creating shavings or fragments that are lodged inside the feed motor.

If operating the drill on Mars somehow created the FOD, engineers might be able to change the way they use the instrument, and improve the design of future drills, such as the device in development to fly on NASA’s Mars 2020 rover, a spacecraft largely based on Curiosity’s design and chassis.

Erickson said the rover team is still examining how to resume drilling with Curiosity, and it is too early to declare that engineers can fully correct the problem, or that the issue will prevent future drillings.

It may turn out that the stalled motor remains intermittent, he said, making it a nuisance for ground controllers commanding the rover, but not fatal for the future of the drill.

Engineers originally thought the problem might be rooted in an encoder associated with electrical sensors that tell the rover’s computer how the drill is functioning. In a press conference Dec. 13, Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada said the problem apparently is with the brake, which is “very much internal to the motor itself.”

Curiosity’s drill works by boring into rock targets with a combination of a percussive, hammering motion and the rotation of the drill bit. Rock powder excavated by the drill goes into a collection chamber, where the material is sifted and sieved for delivery to miniature laboratory instruments on the rover’s science deck.

The target selected for drilling in early December, when the drill feed problem first appeared, was to be the 16th rock drilled by the rover since it landed on Mars in August 2012. It would have been the seventh drilling operation of 2016, according to NASA.

Ground controllers programmed the drill to only use its rotating mechanism on the latest sampling attempt. The percussive mechanism that chisels into rock has had an intermittent electrical short since early 2015, and while that function is still available, officials prefer to avoid using it unless necessary.

Quelle: SN