16.02.2026

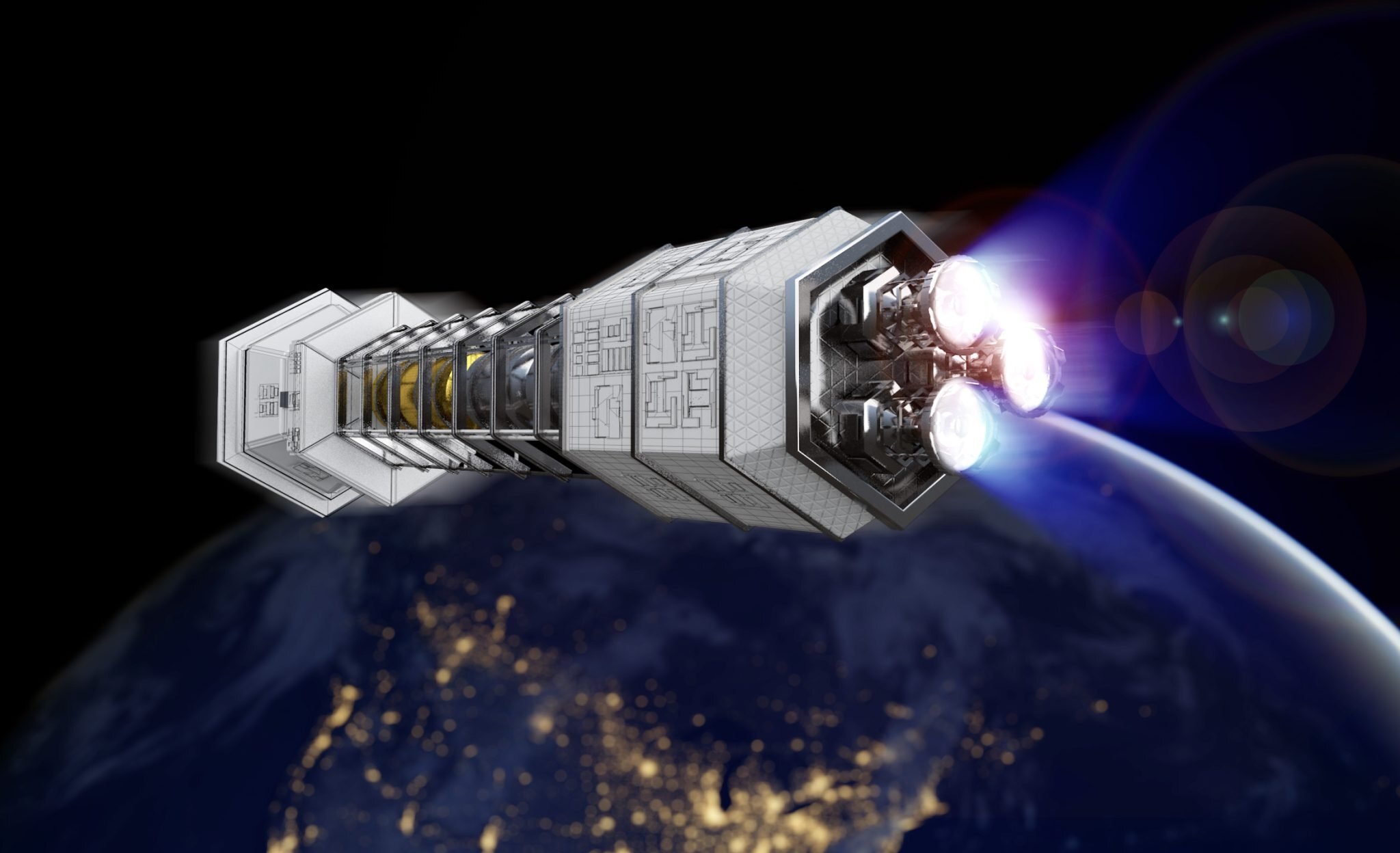

Conceptual rendering of a space nuclear reactor.

Energy is fundamentally important — researchers have linked a lack of reliable energy to poor physical health, poor mental health and higher mortality rates. But when astronauts push the boundaries of space exploration, energy is a matter of life and death.

Finding dependable energy sources for the conditions in space presents a challenge that nuclear science and technology researchers are primed to solve.

Since the 1960s, spacecraft such as Voyager 1 and 2 and the Mars rovers have used radioisotope power systems — devices that use the decay heat of plutonium to generate reliable heat and electricity. While there are no fission-based nuclear reactors currently operating in space, NASA issued a directive on fission surface power and intends to place a reactor on the Moon in fiscal year 2030. To meet this objective, a report funded by the Idaho National Laboratory, Weighing the Future: Strategic Options for U.S. Space Nuclear Leadership, suggests several possible avenues for success.

“It might sound like science fiction, but it’s not,” said Sebastian Corbisiero, the Department of Energy Space Reactor Initiative national technical director. “It is very realistic and can significantly boost what humans can do in space because fission reactors provide a step increase in the amount of available power. What we need now is a clear path forward.”

Special considerations

While much can be leveraged between emerging terrestrial advanced reactors and space-bound fission systems, there are some key differences that present challenges needed to be solved for the space environment. “The big differences are mass, temperature and component endurance,” said Corbisiero.

Everything sent into space must be transported by a rocket, so the reactor must be as light as possible while still being robust and durable. Weight thus becomes a primary focus, said Corbisiero.

For example, water might not be the best coolant choice for space-bound reactors because water would require extremely thick, heavy metal pressure vessels to contain it.

The materials suitable for the extreme conditions inside a terrestrial nuclear reactor may not be suitable for the even more intense conditions a space reactor must endure. To maximize power output, space reactors operate at much higher temperatures.

Also, terrestrial reactors are typically turned off every 18-24 months for part replacement and refueling. In contrast, space reactors are planned to be designed to last 10 years without maintenance. This requires exceptionally durable components and electronics to endure the harsh conditions of space for extended periods – development factors being evaluated by NASA’s Fission Surface Power effort.

Nuclear experts are working to develop and test the proper reactor designs to meet these demanding requirements for a space system.

Potential paths ahead

The earliest work in space nuclear power was performed by the U.S. and the Soviet Union, leading to early reactors like SNAP-10A and decades of energy innovation to support deep space missions. Nearly 70 years later, NASA is collaborating with other federal agencies, national laboratories and private companies to create reliable nuclear reactors to provide power generation for the moon and Mars.

While the U.S. has consistently invested in the development of space-nuclear technologies, the pace of development needs to accelerate for the nation to maintain leadership in space nuclear propulsion and surface power solutions. The report on space nuclear leadership outlines three strategies for consideration:

Go Big or Go Home: This option is designed to make the most impact as quickly as possible by building a large 100-500 kilowatts-electric power project led by NASA or the Department of War, with support from the Department of Energy. The appeal is the potential for a high return on investment but will require consistent, secure, top-down leadership and funding.

Chessmaster’s Gambit: This option acknowledges that a commitment to long-term, high-level funding might not be feasible. The proposal involves two smaller projects, under 100 kilowatts electric, through public-private partnerships. One project, proposed to be led by NASA, would build a power reactor to be placed in the moon’s orbit or on the moon’s surface. The other project, led by the Department of War, would construct an in-space system. This option reduces risk by allowing private companies to choose the technology and fuel to fulfill deadlines and budget constraints.

Light the Path: This cautious and gradual approach involves developing a small — under 1 kilowatt electric — radioisotope power system demonstration. While this option is limited in scope, it helps to establish regulation, historical knowledge and a paved path for private sector institutions.

Given the significant technical and geopolitical implications of space nuclear energy, these strategies offer three viable paths forward, tailored to different investments in time, energy and cost.

The starting line

INL will play a pivotal role in facilitating space nuclear power and propulsion strategies. As the lead national laboratory supporting space reactor efforts, INL coordinates across multiple national laboratories to develop technologies, capabilities and infrastructure needed to ensure mission success.

With specialized staff and state-of-the-art facilities like the Transient Reactor Test Facility, INL is equipped to conduct critical testing of nuclear propulsion reactor fuels and host new reactor technologies on-site. This positions INL as a hub for advancing space reactor technologies, providing the necessary technical expertise and resources to support ambitious projects.

Ambitious strategies are essential to meet our nation’s space nuclear goals, particularly getting a reactor on the moon, Corbisiero said. Accelerating nationwide research and development of these technologies supported by INL will ensure that the U.S. maintains its leadership in this critical area.

“We’re potentially on the cusp of a major step forward regarding nuclear power for space applications,” said Corbisiero. “To be a part of an effort like this — that is as exciting as it gets. That’s something you tell your grandkids.”

Quelle: Idaho National Laboratory