6.03.2020

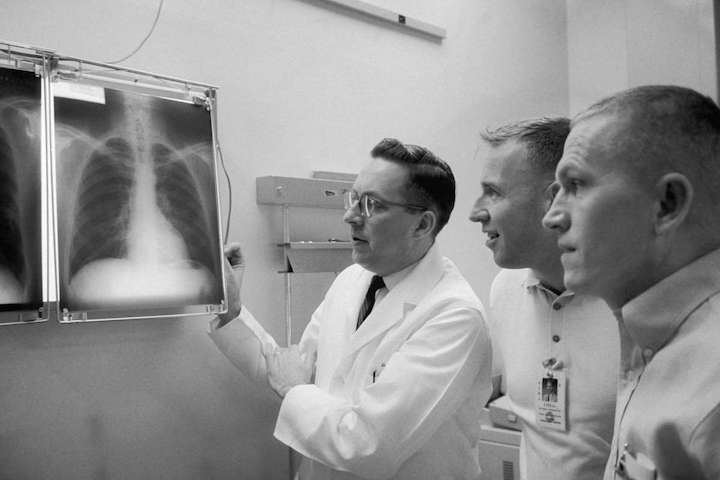

Dr. Charles A. Berry (left), chief of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) Medical Programs, and astronauts James A. Lovell Jr. (center), Gemini-7 pilot, and Frank Borman, Gemini-7 command pilot, examine a series of chest x-rays taken during the preflight physical on Dec. 2, 1965.

Dr. Charles “Chuck” A. Berry, a NASA flight surgeon who helped select the country’s first astronauts and devised tests to see if they could survive the demands of space, died in his sleep over the weekend in his Houston home. He was 96.

Berry is considered a pioneer in aerospace medicine, with a 68-year career in which he served as a flight surgeon for the U.S. Air Force, director of life sciences for NASA, an aviation medical examiner for the Federal Aviation Administration and an aerospace medicine consultant.

“I don’t think aerospace medicine, as a specialty in medicine and as a field, would be where it is today without the influence of all the various things he did at the various points in his career, both within the Air Force and with NASA,” said his son Dr. Michael A. Berry, who also has a specialty in aerospace medicine.

Berry received his medical degree from the University of California San Francisco in 1947. After an internship at the San Francisco General Hospital (now called the Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center), he went into private practice in Indio, Calif.

He joined the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War and moved to San Antonio for a year of training at the U.S. Air Force School of Aviation Medicine (now the Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine). He’d go on to help countries in Central and South America set up their own aviation medicine programs, earn his master’s degree in public health from Harvard University and become chief of the Department of Flight Medicine at the U.S. Air Force School of Aviation Medicine, where he sent pilots in balloons and aircraft to various altitudes to see how their bodies would react physiologically.

This was where his career took a turn that would eventually prompt Berry to leave the Air Force for NASA.

In 1957, Berry was one of the physicians who helped select test pilots — later referred to as astronauts — who would ride in a military rocket into outer space. He then helped select NASA’s first seven astronauts for Project Mercury, the country’s first man-in-space program.

Berry and his fellow physicians devised ways to physically test who could withstand the demands of space, as it was understood at that time.

“We put them in (a chamber) in the dark and suspended them so that they weren’t touching anything,” Berry said in a NASA Johnson Space Center oral history project. “They were suspended with wires, and left them in there for six hours in the dark. Now, that’s dumb when you think about it, because the thing I didn’t like about it, I said, ‘If we ever have an astronaut in this position, that means that we’ve really had a failure somewhere and he’s out of a spacecraft, and it isn’t going to make a lot of difference anyway then. So this doesn’t seem like a very realistic kind of thing to do.’ But we exposed them to heat and cold and ran them on treadmills which were not being used anywhere else at that time. Exposed them in partial pressure suits.”

And they figured out ways to monitor astronauts’ health before they launched — even telling former President Richard Nixon that he could not break the astronauts’ quarantine by eating dinner with them before Apollo 11 — and while in space.

Still, people questioned if humans could survive the journey, citing a lack of data.