16.02.2020

While seeking to reconcile science and religion, Father Coyne also vigorously supported Darwin and challenged believers in intelligent design.

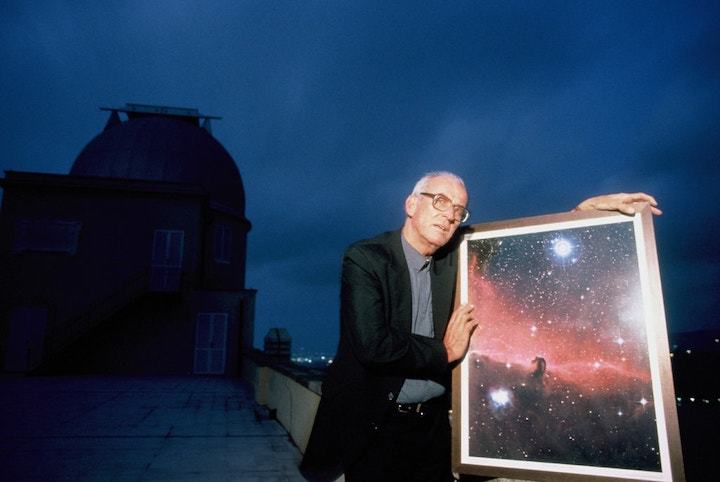

The Rev. George C. Coyne at the Vatican observatory at Castel Gandolfo in 1991. He headed it for nearly three decades, arguing that religion had a place alongside science.Credit...Franco Origlia/Getty Images

The Rev. George C. Coyne, a Jesuit astrophysicist who as the longtime director of the Vatican Observatory defended Galileo and Darwin against doctrinaire Roman Catholics, and also challenged atheists by insisting that science and religion could coexist, died on Tuesday in Syracuse, N.Y. He was 87.

His death, at a hospital, from complications of bladder cancer, was announced by the Jesuit-run Le Moyne College in Syracuse, where he had been a professor of religious philosophy after retiring from the observatory in 2006.

Recognized among astronomers for his research into the birth of stars and his studies of the lunar surface (an asteroid is named after him), Father Coyne was also well known for seeking to reconcile science and religion. He applauded Pope Francis for addressing the role that humans play in climate change, and he challenged alternative theories to evolution like creationism and intelligent design.

“One thing the Bible is not,” he told The New York Times Magazine in 1994, “is a scientific textbook. Scripture is made up of myth, of poetry, of history. But it is simply not teaching science.”

Brother Guy Consolmagno, the current director of the Vatican Observatory, said in an email that Father Coyne “was notable for publicly engaging with a number of prominent and aggressive opponents of the church who wished to use science as a tool against religion.”

Among those he engaged on the debate stage and in print were Richard Dawkins, the English evolutionary biologist and atheist, and Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna, who, in an Op-Ed article in The New York Times in 2005, defended the concept that evolution could not have occurred without divine intervention.

During Father Coyne’s tenure, the Vatican publicly acknowledged that Galileo and Darwin might have been correct. Brother Consolmagno said it would be fair to say that Father Coyne had played a role in shifting the Vatican’s position.

While the church formally acknowledged in 1992 that it had “erred in condemning Galileo” in 1633 for promoting the theory that Earth revolved around the sun, Father Coyle was among the critics who complained that the admission was not only too late but also too little.

In 1996, Pope John Paul II, without defining evolution, said that it was “more than just a hypothesis.” His statement that Darwin’s views had “progressively taken root in the minds of researchers, following a series of discoveries made in diverse spheres of knowledge,” suggested that at least in public schools, religious faith and the teaching of evolution could coexist.