10.02.2020

Iran’s Simorgh rocket suffered its third consecutive launch failure Sunday, incurring the loss of the Zafar-1 satellite. Liftoff took place at around 19:15 Iran Standard Time (15:45 UTC). However, the mission’s failure means that Iran is still waiting for its first successful orbital launch in five years.

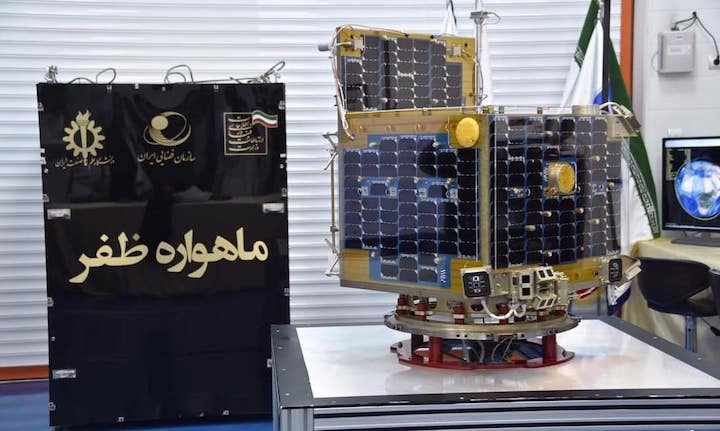

The Zafar-1 satellite which was lost in Sunday’s launch failure was one of a pair of spacecraft Iran had developed for dual-purpose communication and remote sensing mission. The launch appears to have proceeded nominally through its early stages, with an unspecified anomaly likely occurring during second or third-stage flight. No Iranian satellite has reached orbit since Fajr, which launched in February 2015.

Sunday’s launch comes a few days after the eleventh anniversary of Iran’s first successful orbital launch – the deployment of the Omid satellite by a Safir rocket on 2 February 2009. Iran has maintained that its development of rockets for space missions has been to enable self-reliance – as international sanctions and political pressures have made other nations unwilling or unable to cooperate with Iran and launch spacecraft on its behalf.

Iran has continued to stress that its ambitions in space are peaceful. Western nations, however, have often characterized the Iranian space program as a front for the country’s development of missile technology.

Iran’s satellite launches take place from the Imam Khomeini Spaceport, located in Iran’s Semnan Province. This has two main launch pads – the first is used by Safir rockets and the second by Simorgh. Sunday’s launch took place from the second pad. This complex includes support buildings and a mobile service tower to provide access to Simorgh while it is standing on the launch pad. Ahead of Sunday’s launch, the service tower would have been moved to a parked position away from the launch pad.

The Safir rocket that Iran used for its earliest satellite launches was based on the Shahab-3 missile – itself derived the North Korean Hwasong-7 missile which traces its design back to the Soviet Union’s R-17 Elbrus – commonly known in the west as the Scud.

The larger and more powerful Simorgh, which was used for Sunday’s launch and is also known as Safir-2A, is also understood to have been developed with North Korean assistance – and bears visual similarities with the Unha-3 rocket which launched North Korea’s first satellite in December 2012.

The name Simorgh means Phoenix in Farsi. Iran first announced the new rocket in February 2010, displaying a mockup during celebrations to mark the first anniversary of Omid’s launch. At 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) in diameter, Simorgh’s first stage is wider than Safir and is powered by four liquid-fuelled engines to Safir’s one – although the individual engines are thought likely to be the same or similar across the two vehicles. At the top of the first stage, the rocket tapers to a narrower second stage, with a third stage and payload fairing-mounted above this.

Simorgh’s first stage burned hypergolic liquid propellant – likely unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine oxidized by dinitrogen tetroxide. The second stage is believed to have used a similar propellant combination, while few details are known about the third stage and it could have been solid or liquid-fuelled. The Zafar satellite was encapsulated within the rocket’s payload fairing, which separated once the vehicle had cleared Earth’s atmosphere and entered space.

Sunday’s launch appears to have failed during second or third stage flight. Simorgh reached an apogee – the highest point of its trajectory – of 540 kilometers (336 miles, 292 nautical miles), but fell short of orbital velocity by about 1,000 meters per second (2,240 miles per hour).

Simorgh first flew in April 2016, making a suborbital test flight. A first orbital launch attempt occurred in July 2017 – either with the Toulou satellite or a demonstration payload aboard – however, the rocket failed to achieve orbit. Another failure occurred last January when the rocket’s third stage malfunctioned during the attempted launch of the Payam-e Amirkabir satellite. Sunday’s failure to deploy Zafar-1 now marks the rocket’s third consecutive failure, and it is yet to place a satellite into orbit.

The Simorgh vehicle was designed to place a 350 kilogram (771 lb) satellite into a 500-kilometer (310-mile, 270-nautical mile) orbit. While this is a long way behind the rockets operated by most other spacefaring nations, once the current reliability issues have been worked out it will be a significant leap forward for Iran over the Safir’s maximum payload of a little over 50 kilograms (110 pounds). It could also potentially allow Iran to start placing very small satellites into geosynchronous orbit on future launches.

Taking advantage of this increased performance Zafar-1 was the heaviest satellite Iran had attempted to launch to date, tipping the scales at 113 kilograms (249 pounds). Its planned 530-kilometer (329 mi, 286 NM) orbit would have been the highest that Iran had placed a satellite into. The satellite’s name, Zafar, meant “Victory” in the Farsi language.

Had it reached orbit, Zafar would have carried out two missions over a planned eighteen-month lifespan. For its primary remote sensing mission, the spacecraft carried four cameras that can capture color images of the Earth at resolutions of up to 22.5 meters (74 feet). These would have allowed Iran to survey its territory for oil reserves and monitor agriculture, as well as monitoring and studying natural disasters such as earthquakes. Its secondary mission was to have been one of communications, for which it was equipped with a store-dump payload. A user would have been able to upload a message to the satellite which would then have been relayed to receivers as the spacecraft passes overhead.

Zafar was a successor to the Payam-e Amirkabir spacecraft, which was lost in last January’s failure. Anticipating the potential that Sunday’s launch might fail, the backup Zafar-2 satellite has already been assembled and can be made ready for launch. Once the cause of Sunday’s failure has been established, focus will turn to getting the second spacecraft into orbit.

Iran often schedules its launches for early February to mark the anniversary of 1979’s Islamic Revolution, when the country’s monarchy was overthrown, and the current system of government was put in place. Iran’s first successful satellite launch – with Omid in 2009 – marked the revolution’s thirtieth anniversary. Five of Iran’s eleven orbital launch attempts have taken place between the 2nd and 9th of February.

During this year’s celebrations of the anniversary of Omid’s launch – Iran’s National Space Technology Day – the country also reaffirmed plans for future crewed missions. This included the display of a mockup capsule capable of sustaining one astronaut in low Earth orbit and the announcement that five such spacecraft were being procured.

Sunday’s failure continues a run of four launch failures for Iran – which, in addition to Sunday’s launch – includes both previous orbital Simorgh launches and a failed Safir launch last February. These figures do not include a second Safir which reportedly exploded on its launch pad in late August last year, during fuelling operations ahead of another planned launch.

Before Sunday’s launch, Iran was reported to have the second Zafar satellite, Zafar-2, ready to launch quickly in the event of the first satellite’s failure. Since this has now failed, Iran can be expected to move forward with the replacement satellite’s launch aboard another Simorgh rocket as soon as it is practical to do so. Four additional satellites – Pars 1, Pars 2, Nahid 1 and Nahid 2, have also been announced to launch in the coming year.

Despite the failure, with Sunday’s launch, Iran has shown an unprecedented level of transparency with its space program. Details of the launch were circulated ahead of time, including reports that previous launch attempts had been delayed and then on Sunday afternoon that liftoff was imminent. Iran’s state media announced the failure less than an hour after it happened, acknowledging that while the rocket had “successfully” reached space, but had not been able to enter orbit.

This continues a trend from last January’s Simorgh launch failure, where Iran also quickly acknowledged that the launch had not been successful. With earlier failures, Iran had either claimed the launches as successful or simply reported that the planned mission had been delayed.

Ahead of Sunday’s launch, Iran’s Minister of Information and Communications Technology, Mohammad Javad Azari-Jahromi, tweeted that Iran was “not afraid of failure and [would] not lose hope”, while calling on Iranians to pray for a successful mission. After the failure was announced, Jahromi referenced the difficulties other countries – particularly the United States – had experienced with their early satellite launch attempts and maintained that success would follow for Iran.

Quelle: NS