5.04.2018

You probably don't know it, but in early February 87 countries agreed to voluntary guidelines to enhance the long-term sustainability of the space domain, a significant achievement in space diplomacy. Given that it took eight years to reach this agreement on a set of non-legally binding measures that largely reaffirm existing practices, it is not surprising that it was not widely covered in the news. But it matters.

You probably don’t know it, but in early February 87 countries agreed to voluntary guidelines to enhance the long-term sustainability of the space domain, a significant achievement in space diplomacy.

Given that it took eight years to reach this agreement on a set of non-legally binding measures that largely reaffirm existing practices, it is not surprising that it was not widely covered in the news. But it matters.

The agreement was reached during a meeting of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). COPUOS was created in 1959 as the main UN body to govern the exploration and use of space, and was instrumental in the creation of the five major space treaties. It has been the main multilateral forum where countries meet to discuss space issues and share updates on national activities and practices. As of 2018, those eighty-seven countries are formal members of COPUOS, with Bahrain, Denmark and Norway being the most recent additions. There are also nearly 40 observer organizations, including the Secure World Foundation.

After the Chinese anti-satellite test of 2007, the long-term sustainability of space activities increased in salience, becoming a formal agenda item at COPUOS three years later. In 2011, the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee (STSC) of COPUOS approved the creation of a formal Working Group on the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities, commonly referred to as the LTS Working Group. In turn, the LTS Working Group created four Expert Groups that began deliberations on four categories of voluntary guidelines: sustainable space utilization supporting sustainable development on Earth; space debris, space operations and tools to support collaborative space situational awareness; space weather; and regulatory regimes and guidance for actors in the space arena.

In 2016, the first set of 12 guidelines were agreed to by a consensus of all the members of COPUOS, and the mandate of the LTS Working Group was extended through 2018. The most recent meeting of STSC in February 2018 saw the LTS Working Group reach consensus on nine more guidelines and the preamble text, bringing the total to 21, as well as agreeing to review their implementation and potentially update them.

The 21 guidelines represent countries’ best practices across a broad spectrum of space issues. They include:

- enhancing the registration of space objects;

- sharing contact information and space situational awareness data on space objects and events;

- performing conjunction assessment during launch and on-orbit operations to find potential collisions;

- designing satellites to increase their trackability;

- addressing the risks of uncontrolled atmospheric re-entries;

- strengthening national regulatory and oversight frameworks to implement international treaties;

- sharing space weather data and forecasts;

- and promoting awareness of space sustainability.

Several other guidelines still under consideration represent important issues for future space activities: the peaceful nature of space activities; protection of terrestrial space infrastructure; active debris removal and intentional destruction of space objects; dealing with non-registered space objects, safe rendezvous and proximity operations, modification of the space environment, and cyber security. The inability to reach consensus on these issues is more likely due to the topics since they are relatively recent additions to multilateral space discussions, and no discussion at the United Nations can be undertaken independent from geopolitical tensions and ideological divisions.

The first reason the LTS guidelines should be seen as a success is that they managed to do what other recent multilateral space efforts could not do: actually produce a tangible result. Space arms control proponents have long lamented the failure of the Conference on Disarmament (CD), the main UN negotiating body on security agreements, to even agree on an agenda of work, let alone make progress on the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) agenda item. The deadlock at the CD led the European Union to develop a voluntary International Code of Conduct for Space (ICOC) to try and address some of the low-hanging fruit on the space security tree. But that too failed to deliver, mainly due to process failures and the issue of self-defense, and is now mostly dead.

Another space security initiative – the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts on Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Outer Space Activities (commonly called the GGE on TCBMs) – did reach agreement in 2013 by its 15 members on a set of measures to increase cooperation and reduce the risks of misunderstanding, mistrust, and miscalculations. But there has been little follow-through on implementing the GGE’s recommendations in the five years since their creation, leaving many to wonder if that was the end of its line.

The second reason the LTS guidelines are important is that the process for creating them increased the capacity for many countries to contribute to multilateral discussions on space issues. Many countries have only a handful of people focused on space policy, and most of those have space as only one issue in a larger portfolio. As a result, most multilateral space discussions tend to be dominated by a few countries with either strong ideological positions or technical capabilities, with most countries sitting on the sidelines. The creation of the LTS Working Group led many countries to start domestic conversations on the implications of space sustainability for their national interests, and in the process they developed a stronger cadre of national space policy experts along with coordinated national positions. This means that more countries now care about space sustainability issues and can now contribute constructively to such discussions than ever before. Including more countries in the discussions also increases the likelihood of their implementation globally.

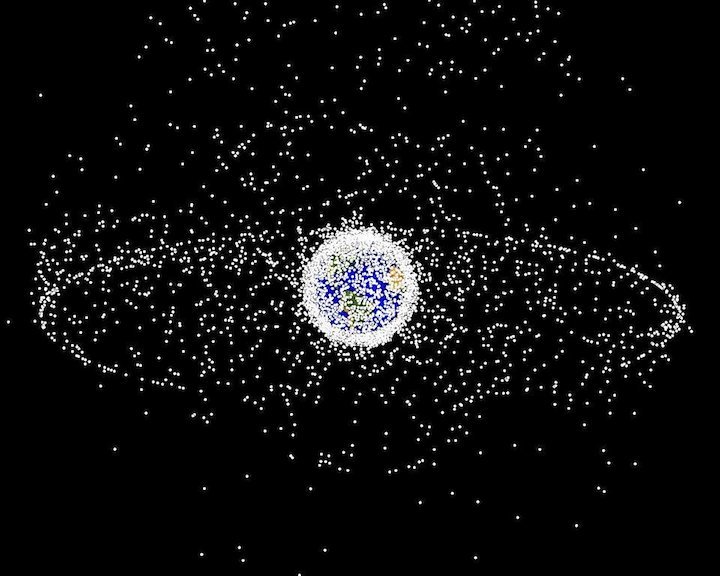

The third reason is that the LTS guidelines will likely have positive benefits for sustainability and stability of the space domain. The guidelines represent the lessons learned from the previous six decades on how to minimize the negative impact of human space activities on the space environment. The hope is that by sharing experiences and documenting best practices, the growing number of countries in space can avoid repeating the painful mistakes of the past. With so many new companies and countries getting into space, it makes sense to try and encourage responsible behavior from the beginning. And while the LTS guidelines are not specifically aimed at resolving security issues, several of them do serve as TCBMs that can help prevent mishaps, misperceptions, and mistrust that could lead to instability or conflict in space. That puts the world in a better position to continue using space for benefits on Earth, while also increasing innovation and economic development of space.

That said, the LTS initiative does have its critics. Russia has expressed concerns about several of the guidelines it proposed not being part of the final agreement and has signaled it may still withdraw its support from the entire effort if their remaining proposals are left hanging. The Latin American countries are also concerned that their proposed guideline on the peaceful nature of space has not been agreed to as a formal guideline and instead most likely will be incorporated in the final preamble. There are also domestic critics in the United States, who see the LTS effort as a thinly-veiled attempt to constrain American power to the benefit of its adversaries.

This is despite the reality that the LTS guidelines consist of practices that the United States already follow, and experts from the Department of Defense were involved in every step of the process to ensure the guidelines would not have an adverse impact on national security space operations. Others contend that following non-binding guidelines may result in the inadvertent creation of binding customary international law, although that view neglects the international legal requirement that their observance follows from a recognized legal obligation of adherence (opinio juris) that voluntary guidelines are clearly not.

There is still much work to be done, and also lessons to be learned from the LTS experience. The most pressing work is to tackle the topics in the remaining guidelines that COPUOS has not been able to reach consensus on. Space traffic management, active debris removal, self-defense, rendezvous and proximity operations, satellite servicing, and cyber security are important issues that will impact the safety, sustainability, and stability of future space activities, and will need to be addressed in UN COPUOS and other fora.

However, reaching consensus on new multilateral agreements is probably getting harder over time, as they will involve a growing number of countries that have a diverse set of interests, capabilities, and positions, along with a burgeoning commercial sector. Existing multilateral fora and processes will need to adapt and perhaps some work will need to shift to the regional level. Either way, the LTS guidelines provide a blueprint for how to work through those challenges, and hope that humanity can get together to help make space more sustainable for all.

Brian Weeden, a former Air Force missileer, is the Secure World Foundation’s director of program planning. Victoria Samson is the foundation’s Washington office director.

Quelle: Breaking Defense