8.10.2017

NASA astronaut Scott Kelly spent a year in space. His recollections of this unprecedented test of human endurance, and the physical toll it took, raise questions about the likelihood of future travel to Mars.

I'm sitting at the head of my dining room table at home in Houston, Texas, finishing dinner with my family: my longtime girlfriend Amiko, my twin brother Mark, his wife, former US congresswoman Gabby Giffords, his daughter Claudia, our father Richie and my daughters Samantha and Charlotte. It's a simple thing, sit ting at a table and eating a meal with those you love, and many people do it every day without giving it much thought. For me, it's something I've been dreaming of for almost a year.

I contemplated what it would be like to eat this meal so many times. Now that I'm finally here, it doesn't seem entirely real. The faces of the people I love that I haven't seen for so long, the chatter of many people talking together, the clink of silverware, the swish of wine in a glass – these are all unfamiliar. Even the sensation of gravity holding me in my chair feels strange, and every time I put a glass or fork down on the table there's a part of my mind that is looking for a dot of Velcro or a strip of duct tape to hold it in place.

Scott Kelly inside a Soyuz simulator ahead of his mission. This capsule would be his escape pod in case of a disaster.

Photo: NASA/Bill Ingalls/Courtesy of Penguin Random HouseIt's March 2016, and I've been back on Earth, after a year in space, for precisely 48 hours. I push back from the table and struggle to stand up, feeling like a very old man getting out of a recliner.

"Stick a fork in me, I'm done," I announce. Everyone laughs and encourages me to get some rest. I start the journey to my bedroom: about 20 steps from the chair to the bed. On the third step, the floor seems to lurch under me, and I stumble into a planter. Of course, it isn't the floor – it's my vestibular system trying to read just to Earth's gravity. I'm getting used to walking again

.

Scott Kelly and partner Amiko in Red Square, Moscow

-

That's the first time I've seen you stumble," Mark says. "You're doing pretty good." A former astronaut, Mark knows from personal experience what it's like to come back to Earth. As I walk by Samantha, I put my hand on her shoulder and she smiles up at me.

I make it to my bedroom without incident and close the door behind me. Every part of my body hurts. All my joints and all of my muscles are protesting the crushing pressure of gravity. I'm also nauseated, though I haven't thrown up. I strip off my clothes and get into bed, relishing the feeling of sheets, the light pressure of the blanket over me, the fluff of the pillow under my head.

All these are things I've missed dearly for the past year. I can hear the happy chatter of my family behind the door, voices I haven't heard for a long time without the distortion of phones bouncing signals off satellites. I drift off to sleep to the comforting sound of their talking and laughing.

A crack of light wakes me: Is it morning? No, it's just Amiko coming to bed. I've only been asleep for a couple of hours but I feel delirious. It's a struggle to come to consciousness enough to move, to tell her how awful I feel. I'm seriously nauseated now, feverish, and my pain has gotten worse. This isn't like how I felt after my last mission. This is much, much worse.

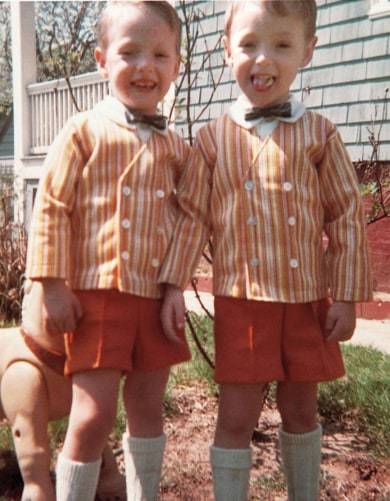

Twin future astronauts Mark (left) and Scott Kelly, in 1967.

-

"Amiko," I finally manage to say. She is alarmed by the sound of my voice.

"What is it?" Her hand is on my arm, then on my forehead.

Her skin feels chilled, but it's just that I'm so hot. "I don't feel good," I say.

Over the past year, I've spent 340 days alongside Russian astronaut Mikhail "Misha" Kornienko on the International Space Station (ISS). As part of NASA's planned journey to Mars, we're members of a program designed to discover what effect such long-term time in space has on human beings. This was my fourth trip to space, and by the end of the mission I'd spent 520 days up there, more than any other NASA astronaut. Amiko has gone through the whole process with me as my main support once before, when I spent 159 days on the ISS in 2010-11. I had a reaction to coming back from space that time, but it was nothing like this.

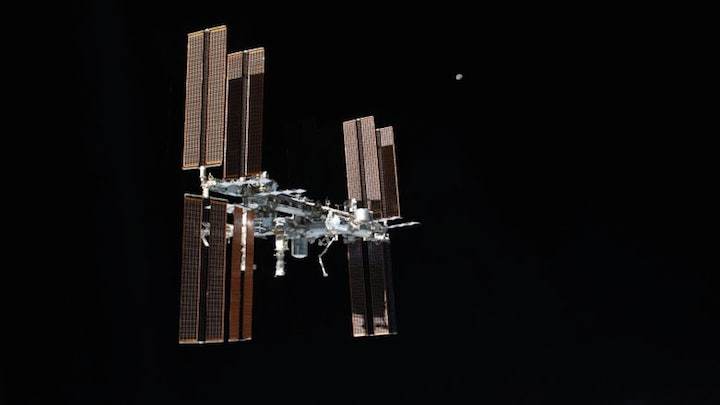

The International Space Station, where Scott Kelly spent 340 consecutive days.

Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House AustraliaI struggle to get up. Find the edge of the bed. Feet down. Sit up. Stand up. At every stage I feel like I'm fighting through quicksand. When I'm finally vertical, the pain in my legs is awful, and on top of that pain I feel a sensation that's even more alarming: it feels as though all the blood in my body is rushing to my legs, like the sensation of the blood rushing to your head when you do a handstand, but in reverse.

I can feel the tissue in my legs swelling. I shuffle my way to the bath room, moving my weight from one foot to the other with deliberate effort. Left. Right. Left. Right. I make it to the bathroom, flip on the light, and look down at my legs. They are swollen and alien stumps, not legs at all. "Oh shit," I say. "Amiko, come look at this." She kneels down and squeezes one ankle, and it squishes like a water balloon. She looks up at me with worried eyes. "I can't even feel your ankle bones," she says.

"My skin is burning, too," I tell her. Amiko frantically examines me. I have a strange rash all over my back, the backs of my legs, the back of my head and neck – everywhere I was in contact with the bed. I can feel her cool hands moving over my inflamed skin. "It looks like an allergic rash," she says. "Like hives."

I use the bathroom and shuffle back to bed, wondering what I should do. Normally if I woke up feeling like this, I would go to the emergency room. But no one at the hospital will have seen symptoms of having been in space for a year. I crawl back into bed, trying to find a way to lie down without touching my rash.

I can hear Amiko rummaging in the medicine cabinet. She returns with two ibuprofen and a glass of water. As she settles down, I can tell from her every movement, every breath, that she is worried about me. We both knew the risks of the mission I signed on for. After six years together, I can understand her perfectly, even in the wordless dark.

As I try to will myself to sleep, I wonder whether my friend Misha, by now back in Moscow, is also suffering from swollen legs and painful rashes. I suspect so. This is why we volunteered for this mission, after all: to discover more about how the human body is affected by long-term space flight. Scientists will study the data on Misha and my 53-year-old self for the rest of our lives and beyond. Our space agencies won't be able to push out farther into space, to a destination like Mars, until we can learn more about how to strengthen the weakest links in the chain that make space flight possible: the human body and mind.

People often ask me why I volunteered for this mission, knowing the risks: the risk of launch, the risk inherent in space walks, the risk of returning to Earth, the risks I would be exposed to every moment I lived in a metal container orbiting the Earth at 28,100 kilometres an hour. I have a few answers I give to this question, but none of them feels fully satisfying to me. None of them quite answers it.

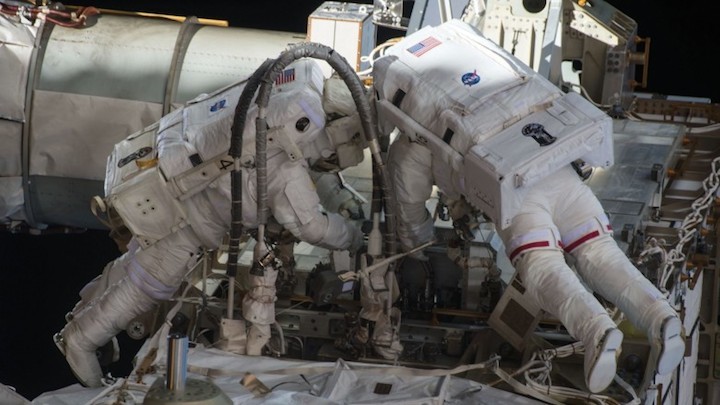

Scott Kelly (at left) undertaking a dangerous space walk outside the International Space Station.

Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House AustraliaA normal mission to the International Space Station lasts five to six months, so scientists have a good deal of data about what happens to the human body in space for that length of time. But very little is known about what occurs after month six. The symptoms may get precipitously worse in the ninth month, for instance, or they may level off. We don't know, and there is only one way to find out.

During our mission, Misha and I collected various types of data for studies on our selves, which took a significant amount of our time. Because Mark and I were identical twins, I also took part in an extensive study comparing the two of us throughout the year, down to the genetic level. The ISS was a world-class orbiting laboratory, and in addition to the human studies of which I was one of the main subjects, I also spent a lot of my time during the year working on other experiments, like fluid physics, botany, combustion and Earth observation.

When I talked about the ISS to audiences, I always shared with them the importance of the science being done there. But to me, it was just as important that the station was serving as a foothold for our species in space. From here, we could learn more about how to push out further into the cosmos. The costs were high, as were the risks.

On my previous flight to the space station, a mission of 159 days, I lost bone mass, my muscles atrophied, and my blood redistributed itself in my body, which strained and shrank the walls of my heart. More troubling, I experienced problems with my vision, as many other astronauts had. I had been exposed to more than 30 times the radiation of a person on Earth, equivalent to about 10 chest X-rays every day. This exposure would increase my risk of a fatal cancer for the rest of my life.

None of this compared, though, to the most troubling risk: that something bad could happen to someone I love while I was in space with no way for me to come home.

I had been on the station for a week, and was getting better at knowing where I was when I first woke up. If I had a headache, I knew it was because I had drifted too far from the vent blowing clean air at my face. I was often still disoriented about how my body was positioned: I would wake up convinced that I was upside down, because in the dark and without gravity, my inner ear took a random guess as to how my body was positioned in the small space. When I turned on a light, I had a sort of visual illusion that the room was rotating rapidly as it reoriented itself around me, though I knew it was actually my brain readjusting in response to new sensory input.

The light in my crew quarters took a minute to warm up to full brightness. The space was just barely big enough for me and my sleeping bag, two laptops, some clothes, toiletries, photos of Amiko and my daughters, a few paperback books. I looked at my schedule for today. I clicked through new emails, stretched and yawned, then fished around in my toiletries bag, attached to the wall down by my left knee, for my toothpaste and toothbrush. I brushed, still in my sleeping bag, then swallowed the toothpaste and chased it with a sip of water out of a bag with a straw. There wasn't really a good way to spit in space.

I didn't get to spend time outside the station until my first of two planned space walks, which was almost seven months in. This was one of the things that some people found difficult to imagine about living on the space station, the fact that I couldn't step outside when I felt like it. Putting on a spacesuit and leaving the station for a space walk was an hours-long process that required the full attention of at least three people on station and dozens more on the ground.

Space walks were the most dangerous thing we did in orbit. Even if the station was on fire, even if it was filling up with poison gas, even if a meteoroid had crashed through a module and outer space was rushing in, the only way to escape the station was in a Soyuz capsule, which also needed preparation and planning to depart safely. We practised dealing with emergency scenarios regularly, and in many of these drills we raced to prepare the Soyuz as quickly as we could. No one had ever had to use the Soyuz as a lifeboat, and no one hoped to.

I opened a food container attached to the wall and fished out a pouch of dehydrated coffee with cream and sugar. I floated over to the hot-water dispenser in the ceiling of the lab, which worked by insert ing a needle into a nozzle on the bag. When the bag was full, I replaced the needle with a drinking straw – this way the liquid didn't escape into the module. It had been oddly unsatisfying at first to drink coffee from a plastic bag sipped through a straw, but now I wasn't bothered by it.

I flipped through the breakfast options, looking for a packet of the granola I liked. Unfortunately, everyone else seemed to like it, too. I chose some dehydrated eggs instead and reconstituted them with the same hot water dispenser, then warmed up some irradiated sausage links in the food warmer box, which looked a lot like a metal briefcase. I cut the bag open, then, since we had no sink, cleaned the scissors by licking them (we each had our own scissors). I spooned the eggs out of the bag onto a tortilla – conveniently, surface tension held them in place – added the sausage and some hot sauce, rolled it up, and ate the burrito while catch ing up with the morning's news on CNN.

All the while I was holding myself in place with my right big toe tucked ever so slightly under a handrail on the floor. Handrails were placed on the walls, floors and ceilings of every module and at the hatches where modules connected, allowing us to propel ourselves through the modules or to stay in place rather than drifting away. There were a lot of things about living in weightlessness that were fun, but eating was not one of them. I missed being able to sit in a chair while eating a meal, relaxing and pausing to connect with other people.

"I missed being able to sit in a chair while eating a meal, relaxing and pausing to connect with other people," writes Kelly of life on the ISS.

Photo: Marco GrobMore than 400 experiments took place on ISS during this expedition. NASA scientists talked about the research falling into two major categories. The first had to do with studies that might benefit life on Earth. These included research on the properties of chemicals that could be used in new drugs, combustion studies that were unlocking new ways to get more efficiency out of the fuel we burnt, and the development of new materials. The second large category had to do with solving problems for future space exploration: testing new life-support equipment, solving technical problems of spaceflight and studying new ways of handling the demands of the human body in space.

Science took up about a third of my time, human studies about three-quarters of that. I had to take blood samples from myself and my crew mates for analysis back on Earth, and I kept a log of everything, from what I ate to my moods. I tested my reaction skills at various points throughout the day. I took ultrasounds of blood vessels, my heart, my eyes and my muscles. I also took part in an experiment called Fluid Shifts, using a device that sucked the blood down to the lower half of my body, where gravity normally kept it. This tested a leading theory about why space flight caused damage to some astronauts' vision.

In fact, there was much crossover between these categories of research. If we could learn how to counteract the devastating impact of bone loss in microgravity, the solutions could well be applied to osteoporosis and other bone diseases. If we could learn how to keep our hearts healthy in space, that knowledge could be useful on Earth.

The effects of living in space looked a lot like the effects of ageing, which affected us all. The lettuce we grew was a study for future space travel – astronauts on their way to Mars will have no fresh food but what they can grow – but it also taught us more about growing food efficiently on Earth. The ISS's closed water system, where we processed our urine into clean water, will be crucial for getting to Mars, but it also has promising implications for treating water on Earth – especially in places where clean water was scarce.

I tell my flight surgeon, Steve, that I feel well enough to get right to work immediately upon returning from space, and I do, but within a few days I feel much worse. This is what it means to have allowed my body to be used for science. I will be a test subject for the rest of my life. A few months after arriving back on Earth, though, I feel distinctly better. I've been travelling the country and the world talking about my experiences in space. It's gratifying to see how curious people are about my mission, how much children instinctively feel the excitement and wonder of space flight, and how many people think, as I do, that Mars is the next step.

I also know that if we want to go to Mars, it will be very, very difficult, it will cost a great deal of money and it may likely cost human lives. But I know now that if we decide to do it, we can.

Edited extract from Endurance: A Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery by Scott Kelly (Doubleday, $35), published on October 19.

Quelle: brisbane times