8.10.2017

Six decades on, it’s still circling our planet.

From his desk at the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, space debris analyst Tim Flohrer keeps track of the 23,000 or so catalogued objects currently orbiting the Earth. They range from spacecraft and satellites – some working, most not – to discarded rocket stages and fragmented space hardware. All of them the result of 60 years of space exploration.

Using radar data from the US Space Surveillance Network (also, primarily, the country’s early warning system) and observations from optical telescopes, Flohrer helps ensure none of this space junk puts operational spacecraft at risk.

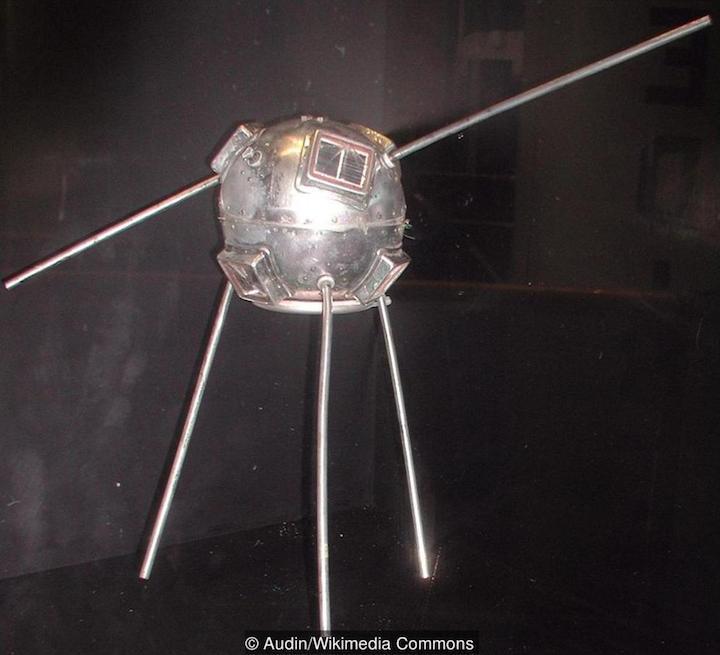

Before we speak, I’ve asked him to check on object 1958-002B, also known as Vanguard 1. Launched in March 1958, this grapefruit-sized shiny metal sphere was boosted into a high elliptical orbit. And it’s still there, passing between 650 and 3,800km (406 to 2,375 miles) from the Earth.

“The earlier satellites, such as Sputnik, have all re-entered the atmosphere,” says Flohrer. “But I estimate that Vanguard 1 will remain in orbit for several hundred, if not a thousand years.”

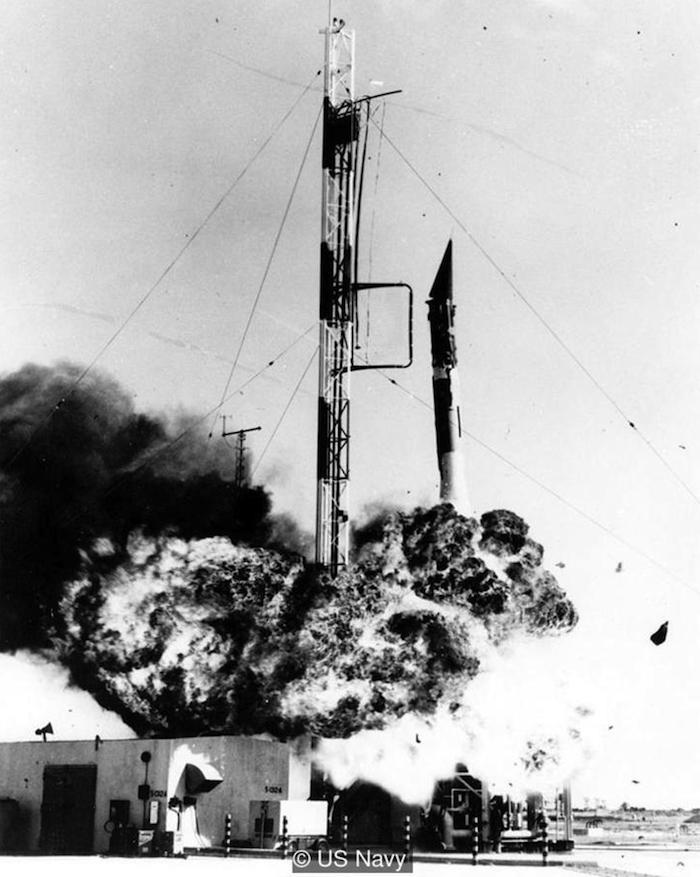

Conceived by the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) in 1955, Vanguard was to be America’s first satellite programme. The Vanguard system consisted of a three-stage rocket designed to launch a civilian scientific spacecraft. The rocket, satellite and an ambitious network of tracking stations would form part of the US contribution to the 1957-58 International Geophysical Year. This global collaboration of scientific research involved 67 nations, including both sides of the Iron Curtain.

“It wasn’t a space race,” says NRL Historian, Angelina Callahan. “The US was always forthright in terms of launch and intended purposes for the satellite but the Soviets held their cards closer to their chest.”

So, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik on 4 October 1957, it came as a shock. “A lot of the disappointment of Sputnik [for the US satellite team] was from the fact that their partners in this international partnership were not telling them they were sending a satellite up,” says Callahan.