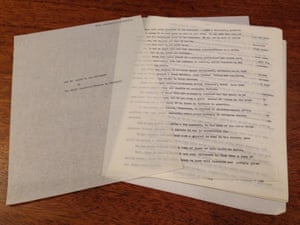

It might never have seen the light of day. Lost and long forgotten, the unpublished essay by Winston Churchill was penned a year before he became Britain’s prime minister. The matter to which he applied his great mind? Not politics, not the battlefield, but the existence of alien life.

The 11-page article was probably intended for the now defunct Sunday newspaper the News of the World, but for reasons unknown the essay remained with his publisher and only recently resurfaced at the US National Churchill Museum at Westminster College in Missouri.

In the essay, Churchill ponders the conditions that make for a habitable world, and on considering the vast number of stars perhaps circled by alien planets, comes to the conclusion that the answer to the essay’s title question, Are We Alone in the Universe?, was surely a resounding “no”.

“The first time I saw it, I thought the combination of Churchill and such a big question had to be a fascinating read, and that proved to be right,” Timothy Riley, the museum’s director, told the Guardian. “It is completely fitting that Churchill would ask such a question. He was keenly interested in science and technological advancement and supported it throughout his long career.” Riley said the museum hopes to make the essay public as soon as it can.

Found by chance in a box at the museum, the newly unearthed article reveals more than Churchill’s ease with scientific thinking. It also shows that as Europe stood on the brink of war, one of the most influential politicians of modern times was hard at work on an article about little green men.

Churchill read keenly on science from an early age. While stationed in India with the British Army, the 22-year-old read a primer on physics and Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. In the 1920s and 1930s he wrote scores of magazine and newspaper pieces on popular science, ranging from nuclear fusion to evolution and cells.

He went on to become the first prime minister to hire a science adviser and created government funding for labs, telescopes and technology which led to post-war discoveries and inventions from molecular genetics to x-ray crystallography.

Writing in the journal Nature, Mario Livio, an astrophysicist and author of an upcoming book, Why? What Makes Us Curious describes how he apparently became the first scientist to read Churchill’s long lost essay on a recent visit to Missouri. “What’s so amazing about the piece is that here is a man, arguably the greatest statesperson of the twentieth century, and in 1939 he not only has the interest, but finds the time, to write an essay about a purely scientific question,” Livio said.

Livio ran a scientist’s eye over Churchill’s essay and was impressed at what he found. “His logic, his train of thought, mirrors exactly what we think today when we think about this question of life elsewhere,” he said.

Churchill starts out by defining what is meant by “life”. Most important, he writes, is the ability to “breed and multiply”. He then moves on to the need for liquid water, an apparent necessity for all living things that still drives the search for alien organisms today.

Modern astronomers talk about stars having a “habitable zone”, a Goldilocks region around them where a planet’s temperature will be neither too hot nor too cold to sustain liquid water. Churchill hit on the same idea, writing that life can only survive “between a few degrees of frost and the boiling point of water.” He was not spot on with every observation. On Earth, some bacteria can survive from -25C to 120C (-13F to 248F).

Churchill was a devoted fan of HG Wells and began his essay shortly after the 1938 US radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds, which whipped up Mars fever in the media. He reasoned that Venus and Mars were the only places in the solar system other than Earth that could harbour life, the other planets being too cold, or on Mercury’s sun-facing side, too hot.

At the time Churchill penned the essay, astronomers favoured a theory that had planets form when stars ripped material off one another as they swept past. Because such encounters were bound to be rare, he reasoned that our sun might be alone in hosting planets. But Churchill proved a good sceptic. “I am not sufficiently conceited,” he writes,” to think that my sun is the only one with a family of planets.” His intuition was right. Astronomers have now spotted thousands of planets beyond the solar system.

Step by step, Churchill reaches a view and expresses it a final sentence that mixes despair with optimism. He writes: “I, for one, am not so immensely impressed by the success we are making of our civilisation here that I am prepared to think we are the only spot in this immense universe which contains living, thinking creatures, or that we are the highest type of mental and physical development which has ever appeared in the vast compass of space and time.”

Richard Toye, professor of history at Exeter University, and author of three books on Churchill, said the great wartime leader wrote scores of newspaper and magazine articles before he took office to fund his expensive lifestyle. It was not unknown for Churchill to jot down notes and pay a ghostwriter to flesh a piece out for him.

“It’s always interesting to find something unpublished by Churchill,” Toye said. “This is definitely the kind of thing that would have stimulated his imagination, and equally he would have seen it as a potentially saleable topic for the various Sunday newspapers and American magazines which he liked to publish in.”

“He always spent more money than was coming in and he always had to sell the rights to something or other to keep himself afloat,” Toye added. “Often he managed to do it by the skin of his teeth.”

At a time when a number of today’s politicians shun science, Livio said he found it moving to recall a leader who engaged with it so profoundly. “It does evoke some nostalgia to a time when high ranking politicians could think about such profound scientific questions,” he said.

Quelle: theguardian