.

28.06.2016

Is China militarising space? Experts say new junk collector could be used as anti-satellite weapon

Craft could be used to attack satellites, according to some researchers

-

A small spacecraft sent into orbit by the Long March 7 rocket launched from Hainan in southern China on Saturday is tasked with cleaning up space junk, according to the government, but some analysts claim it may serve a military purpose.

The Aolong-1, or Roaming Dragon, is equipped with a robotic arm to remove large debris such as old satellites.

Tang Yagang, a senior satellite scientist with the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, said the Aolong-1 was the first in a series of craft that would be tasked with collecting man-made debris in space.

For instance, it could collect a defunct Chinese satellite and bring it back to earth, crashing it safely into the ocean, he said.

“China, as a responsible big country, has committed to the control and reduction of space debris. In order to fulfil the obligations and responsibilities, our country is [working endlessly towards] achieving a technological breakthrough in space debris removal technology,” Tang says on the website of the China National Space Administration.

But the question is: did China develop the cutting-edge technology only to clean up space junk?

“It is unrealistic to remove all space debris with robots. There are hundreds of millions of pieces drifting out there,” said a researcher with the National Astronomical Observatories in Beijing.

To the military, the robot had potential as an anti-satellite weapon, the researcher said.

The Roaming Dragon is small, weighing only a few hundred kilos, so the prototype could be produced and launched in large numbers.

During peacetime, the craft could patrol space and prevent defunct satellites from crashing into big cities such as Shanghai or New York.

During wartime, they could be used as deterrents or directly against enemy assets in space, said the researcher.

It was also a “clean” anti-satellite weapon, the researcher said. In 2007, China conducted an anti-satellite test which blew up a dead weather probe with a missile. The test prompted an international outcry because the explosion generated such a large volume of debris.

“This time no one will point a finger [at China],” the researcher said.

Another mainland space engineering scientist said the role of the craft to pick up space debris was a “bold experiment” with a high chance of failure.

“It looks simple, but some enormous challenges lie ahead, some that no other nation has solved,” said the expert.

The development of the technology was mainly supported by the military, and kept confidential, he said.

The first challenge in such missions was to get close to a “non-cooperative target”, the scientist said.

But China had conducted numerous such rendezvous flights, he said. During the docking of the Shenzhou manned spacecraft to the Tiangong space laboratory, for instance, the two vehicles constantly exchanged information.

“It is unrealistic to remove all space debris with robots. There are hundreds of millions of pieces drifting out there ...”

The Aolong-1, by contrast, would be trying to rendezvous with a piece of cold, unresponsive debris. It would need to search for and identify the target, then plan and adjust its own course of approach.

Another challenge involves reaching out to any debris with Aolong’s robotic arm.

To get a firm grip, the arm must aim for a specific target area – something that in space is likely to be constantly changing.

Sensors and computers on Aolong will have to analyse the fast, irregular patterns of the tumbling target to guide its arm.

Such challenges would test China’s technology to the limit, said the expert.

China is not the only country developing the technology. The European Space Agency is expected to approve a similar project called e.deorbit later this year.

The ESA was considering two different ways to capture the debris: one using a net and the other a robot arm. With a projected launch in 2023, the e.deorbit robot would “target a European derelict satellite in low orbit, capture it, then safely burn it up in a controlled atmospheric reentry,” the ESA says on its website.

The ESA also claims the e.deorbit would be “the world’s first active debris removal mission”, though that is no longer true given the launch of Aolong-1.

The United States Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) plans to launch a larger, more sophisticated craft for the US Air Force in 2020. The Phoenix in-orbit servicing programme had been scheduled for launch last year, but was delayed by technical and cost concerns.

Unlike the Aolong and e.deorbit, the Phoenix would also be able to carry out jobs such as repairing, upgrading and refuelling ageing satellites.

It would even be able to “turn foreign satellites into US spy satellites”, according to the US air force.

Chinese researchers with the 502 Institute at the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation said last year that China would launch a multi-tasking space robot similar to the Phoenix, also by about 2020.

The China National Space Administration says the nation’s blueprint for its space robots spans missions ranging from low earth orbit to Mars.

Quelle: South China Morning Post

-

Update: 6.07.2016

.

Is China’s Mysterious New Satellite Really a Junk Collector—or a Weapon?

The Chinese say the high-tech satellite they launched will clean up space debris, but its extendable robotic arm has some wondering whether it could have a more sinister purpose.

China just boosted a high-tech, mysterious new satellite into orbit. It might be a weapon. It might not be a weapon. There’s no way to be certain, either way—and that’s a problem for all spacefaring countries.

Especially the United States and China. Washington and Beijing are lofting more and more of these ambiguous satellites into orbit without agreements governing their use. In failing to agree to the proverbial rules of the orbital road, the two governments risk ongoing suspicion, or worse—a misunderstanding possibly leading to war.

The Roaming Dragon satellite rode into space atop a Long March 7 rocket that blasted off from Hainan in southern China on June 25. Officially, Roaming Dragon is a space-junk collector. Its job, according to Beijing, is to pluck old spacecraft and other debris from Earth’s orbit and safely plunge them back to the planet’s surface.

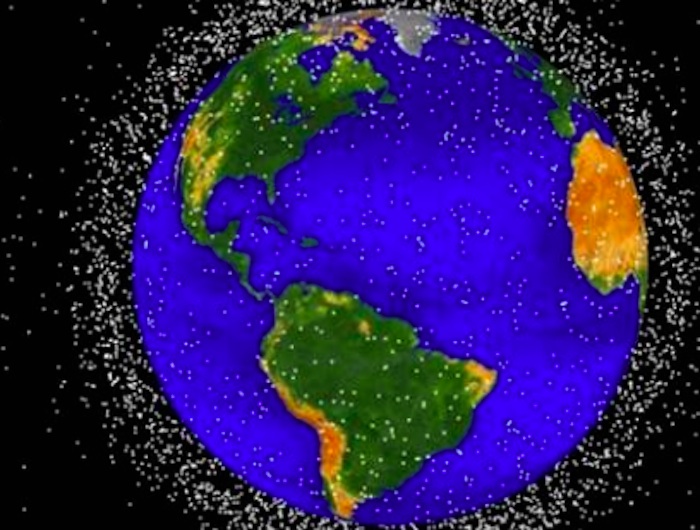

For sure, orbital debris poses a real hazard to the world’s spacecraft. In the summer of 2015, astronauts aboard the International Space Station—including two Russians and an American—sought shelter inside an escape craft when a chunk of an old Russian satellite appeared to be on a collision course with the station.

Luckily, the debris missed the space station. All the same, NASA and other space agencies have voiced their concern over the accumulation of manmade junk in space—and have taken initial steps to remove the most dangerous chunks.

Hence Roaming Dragon’s official mission. “China, as a responsible big country, has committed to the control and reduction of space debris,” Tang Yagang, a scientist with the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, wrote on the Chinese space agency’s website.

But the Roaming Dragon’s design—specifically, its maneuverability and its nimble, extendable robotic arm—mean it could also function as a weapon, zooming close to and dismantling satellites belonging to rival countries.

Stephen Chen, a reporter for the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post—which has historically has been critical of the Chinese central government in Beijing—quoted an unnamed “researcher with the National Astronomical Observatories in Beijing” calling into question the satellite’s purported peaceful mission.

“It is unrealistic to remove all space debris with robots,” the anonymous researcher allegedly stated, implying that Roaming Dragon would, in reality, be doing something else up there in orbit.

But there’s no way to prove that Roaming Dragon is a weapon until it actually attacks another satellite. And at that point, the world would surely have much bigger problems than mere spacecraft taxonomy, as an orbital ambush would almost certainly be a prelude to a much more destructive conflict on the surface.

“Space robotic arms, like many other space technologies, have both military and non-military applications, and classifying them as a space weapon depends on the intent of the user, not on the inherent capabilities of the technology,” Kevin Pollpeter, deputy director of the Study of Innovation and Technology in China Project at the University of California, San Diego, wrote in a widely cited 2013 research paper.

“China’s space robotic arm technology is thus a case study in the challenges of defining ‘space weapon’ and the difficulty in achieving space arms control,” Pollpeter added.

It’s an old problem, by space standards. Jeffrey Lewis, a strategic-weapons expert who blogs at Arms Control Wonk, pointed out in an email to The Daily Beast that NASA’s space shuttle, which first launched into orbit in a dramatic test in 1981, inspired the same worry in Moscow that Roaming Dragon could inspire in Washington.

Specifically, Russian analysts questioned the purpose of the shuttle’s famous “Canadarm”—the Canadian-made “Shuttle Remote Manipulator System” that prominently appears in many photos of the now-retired shuttle’s cargo bay. American analysts are not wrong to point out the potential military applications of Roaming Dragon’s robotic arm. But “the Russians said the same thing about the Canadian arm on the space shuttle,” Lewis told The Daily Beast.

As far as we know, the space shuttle, which last flew in 2011, never attacked another spacecraft. Nor, apparently, have any of the many other spacecraft that possess arms and maneuverability similar to Roaming Dragon—the majority of which, it’s worth noting, are American.

The proliferation of these spacecraft underscores a failure on the part of the world’s governments to agree to orbital codes of conduct. “All the spacefaring countries are developing small satellites capable of conducting so-called autonomous proximity operations—and there are absolutely no rules about this,” Lewis explained.

“If China wants to build an inspector satellite to shadow one of our warning satellites, that’s just ducky as far as space law is concerned. In such an environment, even innocent programs will engender suspicion and initiate the basic arms race dynamics that threaten the use of space for everyone.”

That suspicion is already having a very real effect on the U.S. defense establishment. Growing ever more fearful of a possible ambush in space, in early 2015 Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work instructed John Hyten, the four-star general in charge of U.S. Air Force Space Command, to prepare his space operators and their satellites for a possible war in orbit.

But to a great extent, the paranoia is unjustified, according to Brian Weeden, a former Air Force space operator who is now a technical adviser to the Secure World Foundation in Colorado. “A lot of the so-called space weapons technologies that have been hyped by pundits or the media for decades are not actually very good weapons,” Weeden told The Daily Beast in an email.

For starters, it’s hard for a killer satellite to sneak up on one of America’s own spacecraft, what with NASA and the Air Force constantly monitoring Earth’s orbit via radar and telescope. “We would notice it maneuvering to match orbits with the target hours [or] days in advance,” Weeden said.

For that reason, “there are better, faster, or cheaper ways to accomplish the same goal” of knocking out a satellite, Weeden added.

Ground-based rockets, for example. The same boosters that propel satellites into orbit can, if aimed carefully, strike and destroy spacecraft in certain orbits. China famously tested a so-called direct-ascent satellite-killing rocket in 2007, striking an old weather sat and scattering thousands of pieces of debris—ironically, the same kind of debris Roaming Dragon ostensibly was designed to help clean up.

“I still worry a lot more about China’s direct-ascent ASAT,” Lewis said, using a popular acronym for an anti-satellite weapon.

Contrary to the South China Morning Post’s reporting, it’s entirely possible that Roaming Dragon is what Beijing claims it is—an orbital trash-collector. “It’s not crazy to think about trying to pull large pieces of junk out of high-traffic orbits, since those are potential sources of thousands of pieces of deadly smaller debris if the piece breaks up,” Gregory Kulacki, a space expert with the Massachusetts-based Union of Concerned Scientists, told The Daily Beast in an email.

And to China’s credit, it apparently has been fairly transparent about Roaming Dragon—more transparent, in fact, than the United States is with many of its own spacecraft. Weeden said Chinese officials could go a step further in reassuring the world about Roaming Dragon’s mission. “They could release details of its orbit and provide advance notification of any maneuvers. That would set a very good example for other countries testing similar capabilities to follow, including the United States.”

As long as there’s such a fine line between war and peace in space, bold acts of transparency are the only way to prevent suspicion and conflict. That applies to Roaming Dragon and any other satellite—be it Chinese, American, Russian, or other—that can transform from an instrument of science to a weapon of war with the flip of a few switches.

“We should probably try talking to each other about it,” Lewis advised.

Quelle: THE DAILY BEAST

4877 Views