.

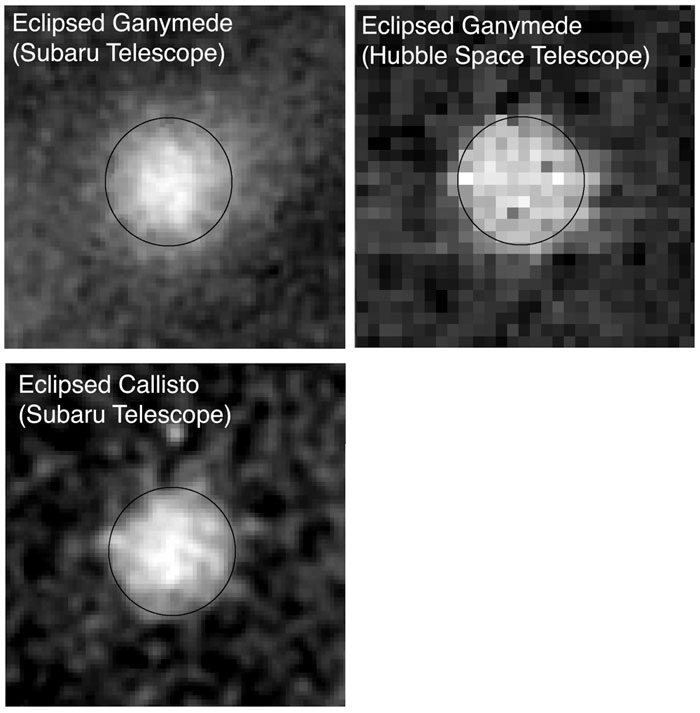

These images show Ganymede and Callisto eclipsed by Jupiter. obtained during their eclipse.

.

Surprise! Big Jupiter Moons Shine Even When Eclipsed

.

Jupiter's largest moons don't go completely dark when the giant planet blocks their sunlight, astronomers have found.

The discovery could reveal more about Jupiter's mysterious upper atmosphere, which the researchers suspect is responsible for keeping the moons lit when they are not directly illuminated by the sun. This research could also help scientists better understand the atmospheres of alien planets, study team members said.

Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, has 67 known moons — more than any other known planet. Jupiter's four largest moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — are known as the Galilean satellites, after their discoverer, famed astronomer Galileo Galilei.

The researchers made their discovery about the Galilean moons accidentally. Their original plan was to detect the diffuse light from the most distant parts of the universe. They wanted to find dark objects in space that could block this far-off light. The difference in brightness between those dark objects and the surrounding sky could then help them determine how bright the diffuse and distant light is.

The researchers assumed the Galilean satellites would be dark while immersed in Jupiter's shadow. As such, they "planned to use the Galilean satellites in eclipse as 'occulters' to block distant background emissions," said lead study author Kohji Tsumura, an astronomer at Tohoku University in Japan.

.

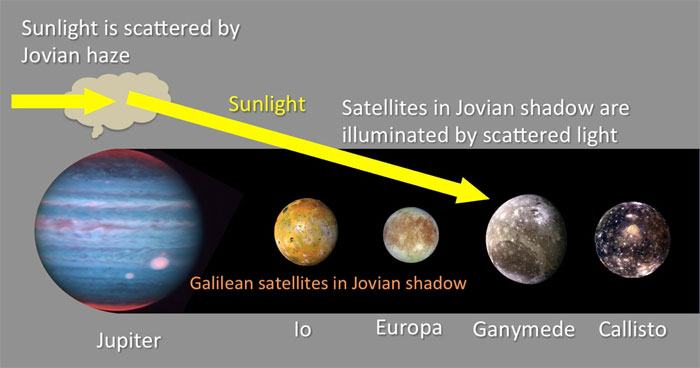

A schematic image of the model shows Jovian shadow eclipsing the Galilean satellites and illuminating the moons by scattered sunlight created in the haze of the Jovian upper atmosphere

Credit: NAOJ/JAXA/Tohoku University/NASA

.

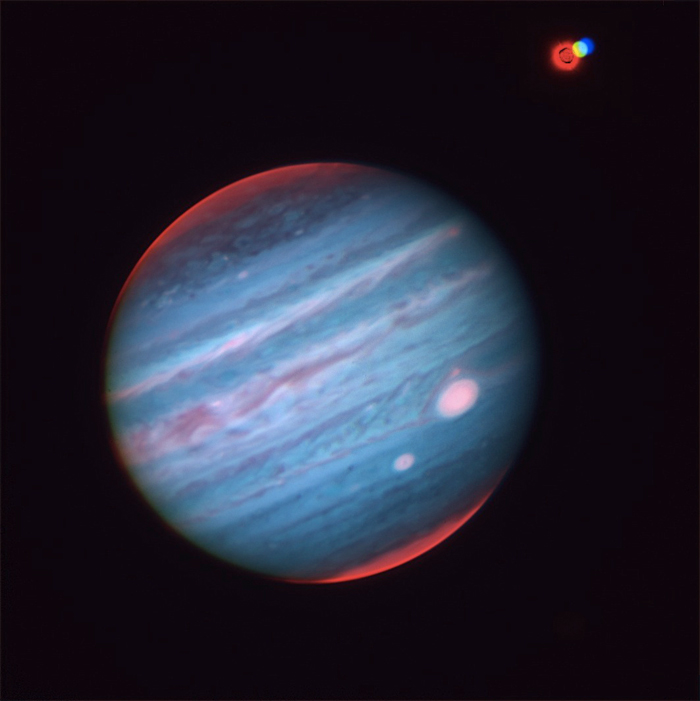

Instead, using the Subaru Telescope and Hubble Space Telescope, the researchers found an unexpected surprise: The Galilean satellites were still slightly bright even when eclipsed. This effect is especially pronounced for Ganymede and Callisto.

"This is a serendipitous discovery, which makes us surprised and excited," Tsumura told Space.com.

Making this discovery was very challenging because the Galilean satellites are extremely faint while eclipsed, and the incredibly bright face of Jupiter near them can blind attempts to see them. Furthermore, the eclipses only take place at specific times, and Jupiter and its moons are continuously in motion, which makes observations very complex, the researchers said.

All in all, when eclipsed, the luminosity of these moons was one-millionth to one-ten-millionth of their uneclipsed brightness — dim enough for the phenomenon to remain undetected until now, even though researchers have observed the Galilean moons in eclipse for centuries.

It remains uncertain what causes the slight brightening. However, Tsumura and his colleagues believe the upper part of Jupiter's atmosphere may be responsible.

.

Jupiter's clouds, which give the giant planet its striped appearance, grow from tiny particles called aerosols or hazes. Prior studies have hinted that these hazes form in the upper part of Jupiter's atmosphere. The researchers suggested that hazes in the upper atmosphere may scatter sunlight onto the Galilean satellites, illuminating them. This effect is similar to the one that causes Earth's moon to look red during a total lunar eclipse.

The new finding could help scientists analyze the hazes in Jupiter's atmosphere, which are otherwise difficult to study. By studying the spectrum of light from the eclipsed Jupiter moons, the researchers could learn about the compositions of the hazes, Tsumura said.

In addition, this new method of studying Jupiter's upper atmosphere could help researchers investigate the atmospheres of exoplanets around distant stars. Exoplanets are often seen when they pass in front of their stars, and scientists can glean details about their atmospheres when starlight passes through them.

"It is important to study sunlight transmitted through the atmospheres of the planets in our solar system for comparison with light through the atmospheres around the exoplanets," Tsumura said.

Tsumura and his colleagues detailed their findings in the July 10 issue of The Astronomical Journal.

Quelle: SC

5346 Views