3.07.2020

- University of Warwick-led team discovers first exposed core of a planet

- Highly unusual planet found in the Neptunian Desert, where such massive objects are rarely seen

- Could be a ‘failed’ gas giant – or one where its atmosphere was ripped away

- Provides a unique opportunity to analyse the interior of a planet first-hand

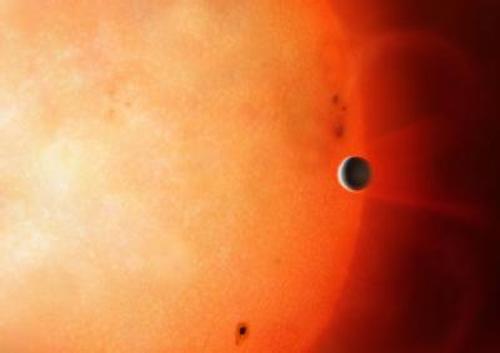

- Artist’s illustration available, see Notes to Editors

The surviving core of a gas giant has been discovered orbiting a distant star by University of Warwick astronomers, offering an unprecedented glimpse into the interior of a planet.

The core, which is the same size as Neptune in our own solar system, is believed to be a gas giant that was either stripped of its gaseous atmosphere or that failed to form one in its early life.

The team from the University of Warwick’s Department of Physics reports the discovery today (1 July) in the journal Nature, and is thought to be the first time the exposed core of a planet has been observed.

It offers the unique opportunity to peer inside the interior of a planet and learn about its composition.

Located around a star much like our own approximately 730 light years away, the core, named TOI 849 b orbits so close to its host star that a year is a mere 18 hours and its surface temperature is around 1800K.

TOI 849 b was found in a survey of stars by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), using the transit method: observing stars for the tell-tale dip in brightness that indicates that a planet has passed in front of them. It was located in the ‘Neptunian desert’ – a term used by astronomers for a region close to stars where we rarely see planets of Neptune’s mass or larger.

The transit signal was confirmed and refined using observations with ten telescopes of the Warwick-led Next-Generation Transit Survey (NGTS), based at the European Southern Observatory’s Paranal Observatory in Chile. The NGTS telescopes were specifically designed to detect the very shallow dips in brightness from exoplanets transits: in this case only a tenth of one percent of the star brightness.

The object was then analysed using the HARPS instrument, on a program led by the University of Warwick, at the European Southern Observatory’s La Silla Observatory in Chile. This utilises the Doppler effect to measure the mass of exoplanets by measuring their ‘wobble’ – small movements towards and away from us that register as tiny shifts in the star’s spectrum of light.

The team determined that the object’s mass is 2-3 times higher than Neptune but it is also incredibly dense, with all the material that makes up that mass squashed into an object the same size.

Lead author Dr David Armstrong from the University of Warwick Department of Physics said: “While this is an unusually massive planet, it’s a long way from the most massive we know. But it is the most massive we know for its size, and extremely dense for something the size of Neptune, which tells us this planet has a very unusual history. The fact that it’s in a strange location for its mass also helps - we don’t see planets with this mass at these short orbital periods.

“TOI 849 b is the most massive terrestrial planet – that has an earth like density – discovered. We would expect a planet this massive to have accreted large quantities of hydrogen and helium when it formed, growing into something similar to Jupiter. The fact that we don’t see those gases lets us know this is an exposed planetary core.

“This is the first time that we’ve discovered an intact exposed core of a gas giant around a star.”

There are two theories as to why we are seeing the planet’s core, rather than a typical gas giant. The first is that it was once similar to Jupiter but lost nearly all of its outer gas through a variety of methods. These could include tidal disruption, where the planet is ripped apart from orbiting too close to its star, or even a collision with another planet. Large-scale photoevaporation of the atmosphere could also play a role, but can’t account for all the gas that has been lost.

Alternatively, it could be a ‘failed’ gas giant. The scientists believe that once the core of the gas giant formed then something could have gone wrong and it never formed an atmosphere. This could have occurred if there was a gap in the disc of dust that the planet formed from, or if it formed late and the disc ran out of material.

Dr Armstrong adds: “One way or another, TOI 849 b either used to be a gas giant or is a ‘failed’ gas giant.

“It’s a first, telling us that planets like this exist and can be found. We have the opportunity to look at the core of a planet in a way that we can’t do in our own solar system. There are still big open questions about the nature of Jupiter’s core, for example, so strange and unusual exoplanets like this give us a window into planet formation that we have no other way to explore.

“Although we don’t have any information on its chemical composition yet, we can follow it up with other telescopes. Because TOI 849 b is so close to the star, any remaining atmosphere around the planet has to be constantly replenished from the core. So if we can measure that atmosphere then we can get an insight into the composition of the core itself.”

- 'A remnant planetary core in the hot-Neptune desert' will be published in Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2421-7

- Dr Armstrong's research was supported by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), part of UK Research and Innovation, through an Ernest Rutherford Fellowship.

Quelle: University of Warwick