30.06.2020

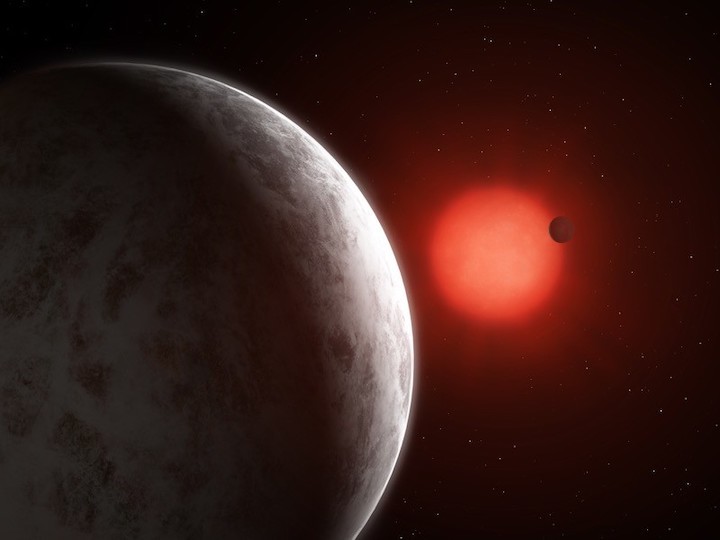

Astronomers have discovered two planets a little more massive than Earth orbiting a nearby star. Unlike many other stars hosting planetary systems, this one is relatively inactive — so it doesn’t emit flares of energy that could hurt the chances of life existing on the planets.

“It’s the best star in close proximity to the Sun to understand whether its planets have atmospheres and whether they have life,” says Sandra Jeffers, an astronomer at Göttingen University in Germany who led the discovery team. The finding was published on 25 June in Science1.

The star, called GJ 887, is just under 3.3 parsecs (10.7 light years) from Earth, in the constellation Piscis Austrinus. It is the brightest red-dwarf star visible from Earth.

Red dwarfs are smaller and cooler than the Sun, and many have planets orbiting them. But most are very active, with magnetic energy roiling their surface and releasing floods of charged particles into space during eruptions known as stellar flares. Many famous planetary systems orbit active red-dwarf stars, such as Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun, and TRAPPIST-1, which has seven Earth-sized worlds. Astronomers say the planets in these systems might not be able to support life, because their stars constantly blast them with powerful radiation.

By contrast, planets in the newfound system could survive relatively unscathed. “GJ 887 is exciting because the central star is so quiet,” says Jeffers. “That’s the exceptional part.”

Her team used several methods to measure GJ 887’s activity. NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) space telescope observed the star for several weeks, as did groups of amateur astronomers; they saw hardly any flickering in brightness, which suggests it is quite stable. The researchers also studied spectroscopic features of different wavelengths of light from the star, which would show whether it was bursting with energy. By that measure, too, GJ 887 is not active.

But it might not always have been so calm, says James Davenport, an astronomer at the University of Washington in Seattle. The planets have been orbiting GJ 887 for billions of years, and the star could have been more active in its youth. “So while GJ 887 is maybe a quiet and cosy place now, it probably had a more hazardous environment when these planets were forming,” he says.

If so, then the star could have spit out enough energetic flares to destroy any early atmospheres that formed on the planets — stripping them down to bare, sterile rock, says Eliza Kempton, an astronomer at the University of Maryland in College Park. “We just can’t say for sure whether they have atmospheres,” she says.

Planets spotted

Jeffers and her colleagues discovered the planets by watching the star every night for three months with a 3.6-metre telescope at the European Southern Observatory in La Silla, Chile. Over time, the star’s motion wobbled a tiny bit as the planets’ gravity tugged on it. “We’ve been looking for signals in this star for 20 years,” Jeffers says. “It’s been such hard work.”

One of the planets is at least 4.2 times the mass of Earth and whizzes around the star once every 9 days. The other is at least 7.6 times the mass of Earth and orbits the star every 22 days.

They are both too close to the star to be able to host liquid water on their surfaces — a measure that astronomers use to decide whether a planet is considered habitable. But both are probably rocky, like Earth, and the planet with a 22-day orbit could be swaddled in a thick atmosphere, Jeffers says. The star’s wobbling also hints at a possible third planet that could lie further away than the other two, orbiting every 51 days and in GJ 887’s habitable zone.

“What I think is awesome is showing once again that nearly every star in the sky, even the many small ones, has planets,” Davenport says. “When we study very nearby stars like these, we have the chance to really characterize and understand the systems.”

Quelle: nature