6.06.2018

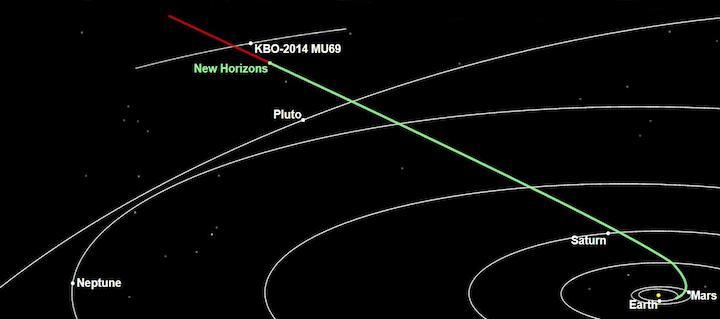

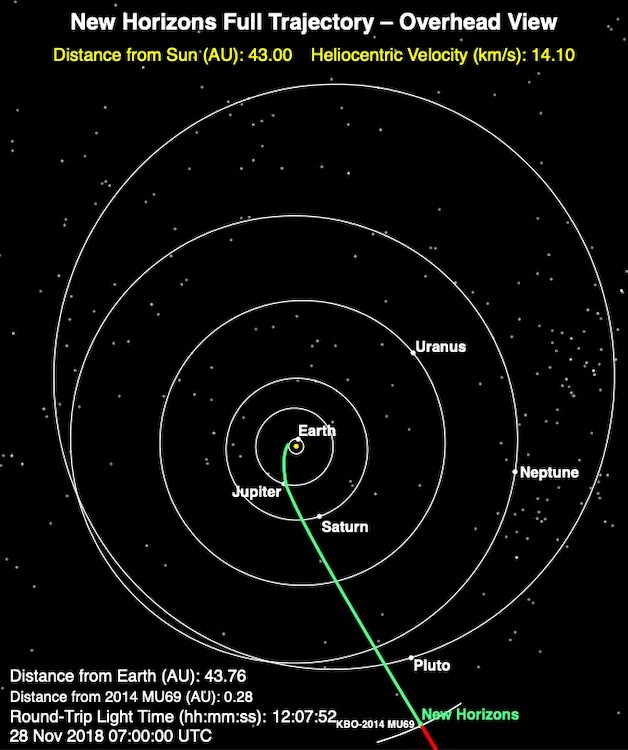

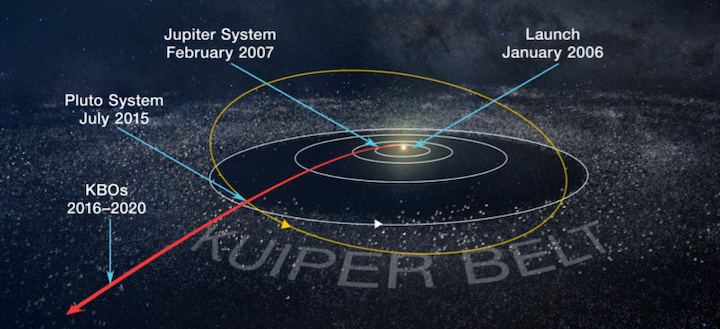

The New Horizons spacecraft has come out of hibernation to begin preparations for its January 2019 flyby of the Kuiper Belt object (KBO) 2014 MU69, nicknamed “Ultima Thule”. The flyby, set to occur in the early morning of January 1, 2019, will be the second for New Horizons, following its historic 2015 Pluto flyby. It will also be the furthest flyby from Earth ever performed by a spacecraft.

2014 MU69 flyby

Initial searches for a post-Pluto flyby target for New Horizons began in 2011, 4 years before its flyby of Pluto. The New Horizons team was aiming for potential KBOs around 50-100km in diameter.

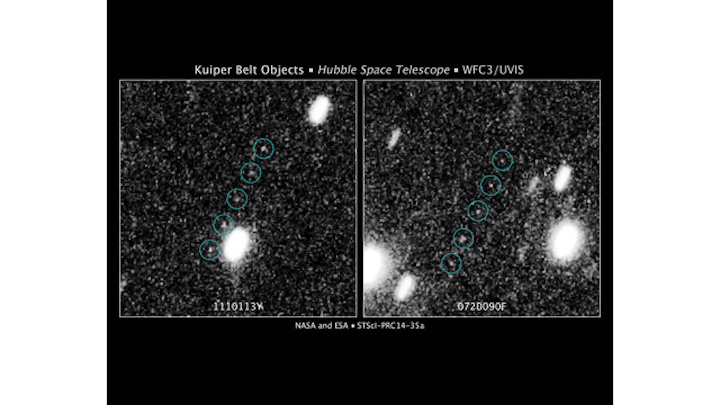

At first, only large ground-based telescopes were used in the search but were unable to find any KBOs that New Horizons could reach with its limited fuel supply. Eventually, the Hubble Space Telescope took over the search, and discovered three possible targets for the flyby, given the temporary names “PT1”, “PT2”, and “PT3”, with the “PT” standing for “Potential Target”.

PT1 and PT3 were seen as the best targets, while PT2 was dropped due to it being further away from New Horizon’s path than the two others. Both PT1 and PT3 had their advantages and disadvantages. For example, PT1 would require less fuel to get to than PT3, but is likely smaller than PT3.

On August 28, 2015, the New Horizons team announced they had chosen PT1 – which was given the temporary name “2014 MU69” – as the flyby target.

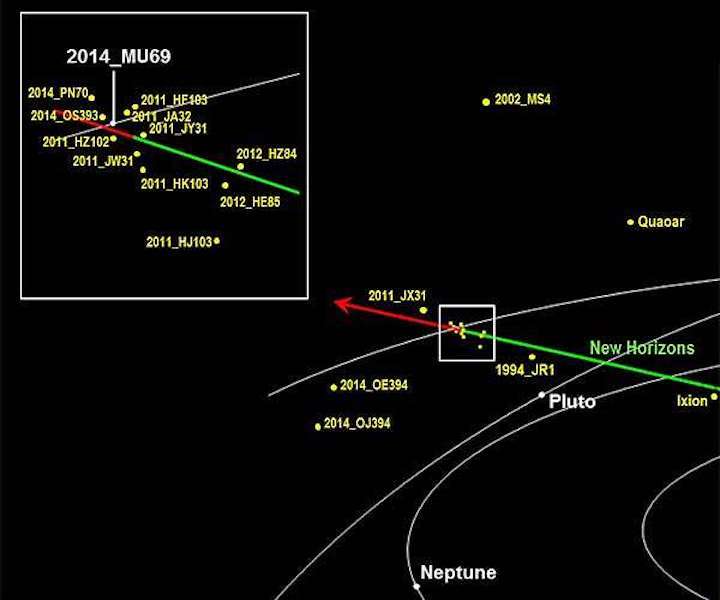

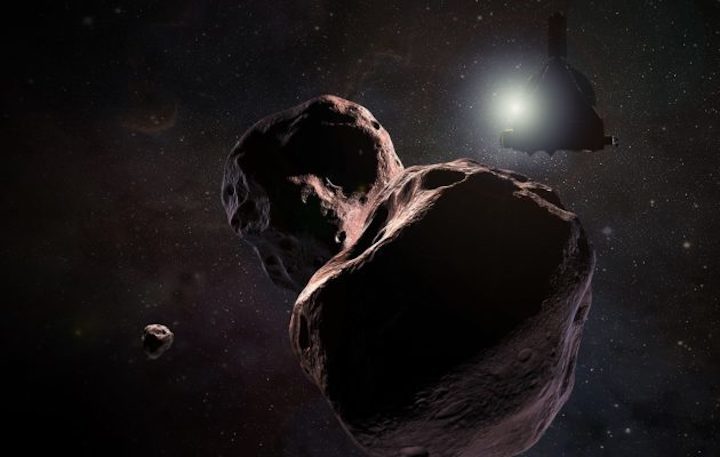

From multiple observations by Hubble and other ground-based telescopes, MU69 was determined to be red, around 30km in diameter, and potentially a binary system. By observing MU69’s shape as it passed in front of background stars – called on occultation – astronomers found that MU69 may be double-lobed – meaning that it could be comprised of two large, connected sections – or a binary system, composed of two similar objects orbiting each other.

An example of a binary system is Pluto and its largest moon, Charon. Although they are not the same size, both objects orbit around a barycenter – a point of gravity between the two objects.

In October and November 2015, four maneuvers were performed by New Horizon’s hydrazine-fueled engines to set it up for a flyby of MU69 in January 2019. In 2017, two small correction maneuvers were performed with the engines in order to further refine the flyby.

On March 13, 2018, using public input from online polls and user-submitted names, MU69 was given the nickname “Ultima Thule” by the New Horizons team – meaning beyond the borders of the known world.

New Horizons will begin its approach phase of the MU69 flyby on August 16, 2018, when it will begin imaging MU69 and the area around it to begin acquiring data about the KBO and its surroundings. Also, New Horizons will look for potential debris that could pose a hazard to itself, such as moons or rings.

Should any potential dangers be found, New Horizons has four planned opportunities to make trajectory changes from early October to early December 2018. The backup trajectory has a distance from MU69 of 10,000 kilometers (around 6,200 miles). Using the backup trajectory would lead to less and/or lower-quality science data gathered due to the probe flying by MU69 further away than planned.

The approach phase will last from August 16 to December 24, 2018, after which the core phase will begin.

The core phase begins just one week before the flyby and continues until two days afterward. It contains the flyby and the majority of the data gathering.

Should all go to plan and the backup trajectory not be used, the MU69 flyby will occur at 5:33 UTC on January 1, 2019, and New Horizons will pass 3,500 kilometers (about 2,100 miles) above MU69’s surface.

Following the flyby, data downlink from New Horizons will begin. On January 1 and 2, the most important data will be downlinked, and the remainder will be transmitted back to Earth from January 9 through most of 2019.

Throughout 2019, New Horizons will also be observing distant KBOs when it is not busy transmitting science data back to Earth.

While in hibernation mode, most of the spacecraft is powered down, including the computers and instruments onboard the spacecraft. Every Monday in hibernation, the computers onboard the spacecraft send a quick signal back to Earth confirming that the spacecraft is healthy. A more detailed analysis of the spacecraft’s systems is sent back once per month.

Hibernation is beneficial to the spacecraft systems and the team. Since the spacecraft is mostly unpowered during hibernation, the instruments and computers onboard the spacecraft won’t be constantly running, which will lengthen their lifespan.

Also, according to New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, shutting down the spacecraft’s systems saves operations costs, as resources don’t need to be used to monitor the downlink of telemetry from the spacecraft and checking its systems.

Additionally, putting New Horizons into hibernation frees up team members from working on telemetry and monitoring the spacecraft’s health, letting more of the team help plan the flyby and the events leading up to and after it.

New Horizons came out of hibernation on Monday and will now undergo an extensive health check, ensuring that all spacecraft instruments, computers and other systems are working properly.

When the health check is complete, New Horizons will enter the approach phase. The approach phase will last from August 16 to December 24, during which New Horizons will make preliminary observations of MU69 and continually monitor for any potential dangers in its path.

The core phase will follow the approach phase and contains the flyby of MU69. The core phase lasts from one week before the flyby to two days after. Once the flyby is completed, data downlink will begin.

According to Mr. Stern, New Horizons may be able to perform one or two more flybys after MU69, and the team is searching for potential targets after the MU69 encounter. New Horizon’s funding currently lasts until 2021, but an extension for that is highly likely, as long as the probe continues to function properly.

New Horizons is estimated to be able to function until around 2037, with the main factor being the amount of power the radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) can provide to the spacecraft.

Quelle: NS

+++

New Horizons Wakes for Historic Kuiper Belt Flyby

Flight controllers Graeme Keleher and Anisha Hosadurga, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, monitor New Horizons shortly after confirming the NASA spacecraft had exited hibernation on June 5, 2018. (Image Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Mike Buckley)

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft is back "awake" and being prepared for the farthest planetary encounter in history – a New Year's Day 2019 flyby of the Kuiper Belt object nicknamed Ultima Thule.

Cruising through the Kuiper Belt more than 3.7 billion miles (6 billion kilometers) from Earth, New Horizons had been in resource-saving hibernation mode since Dec. 21. Radio signals confirming that New Horizons had executed on-board computer commands to exit hibernation reached mission operations at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, via NASA's Deep Space Network at 2:12 a.m. EDT on June 5.

Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of APL reported that the spacecraft was in good health and operating normally, with all systems coming back online as expected.

Over the next three days, the mission team will collect navigation tracking data (using signals from the Deep Space Network) and send the first of many commands to New Horizons' onboard computers to begin preparations for the Ultima flyby; lasting about two months, those flyby preparations include memory updates, Kuiper Belt science data retrieval, and a series of subsystem and science-instrument checkouts. In August, the team will command New Horizons to begin making distant observations of Ultima, images that will help the team refine the spacecraft's course to fly by the object.

"Our team is already deep into planning and simulations of our upcoming flyby of Ultima Thule and excited that New Horizons is now back in an active state to ready the bird for flyby operations, which will begin in late August," said mission Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

New Horizons made a historic flight past Pluto and its moons on July 14, 2015, returning data that has transformed our view of these intriguing worlds near the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt. Since then, New Horizons has been speeding deeper into this distant region, observing other Kuiper Belt objects and measuring the properties of the heliosphere while heading toward the flyby of Ultima Thule -- about a billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) beyond Pluto – on Jan. 1, 2019.

New Horizons is now approximately 162 million miles (262 million kilometers) – less than twice the distance between Earth and the Sun – from Ultima, speeding 760,200 miles (1,223,420 kilometers closer each day. Follow New Horizons on its voyage at http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/Mission/Where-is-New-Horizons/index.php.

Long-Distance Numbers

On June 5, 2018, New Horizons was nearly 3.8 billion miles (6.1 billion kilometers) from Earth. From there – more than 40 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun – a radio signal sent from the spacecraft at light speed reached Earth 5 hours and 40 minutes later.

The 165-day hibernation that ended June 4 was the second of two such "rest" periods for the spacecraft before the Ultima Thule flyby. The spacecraft will now remain active until late 2020, after it has transmitted all data from the Ultima encounter back to Earth and completed other Kuiper Belt science observations.

Quelle: NASA

---

Update: 29.08.2018

.

Ultima in View

New Horizons Makes First Detection of Kuiper Belt Flyby Target

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft has made its first detection of its next flyby target, the Kuiper Belt object nicknamed Ultima Thule, more than four months ahead of its New Year's 2019 close encounter.

Ultima in View

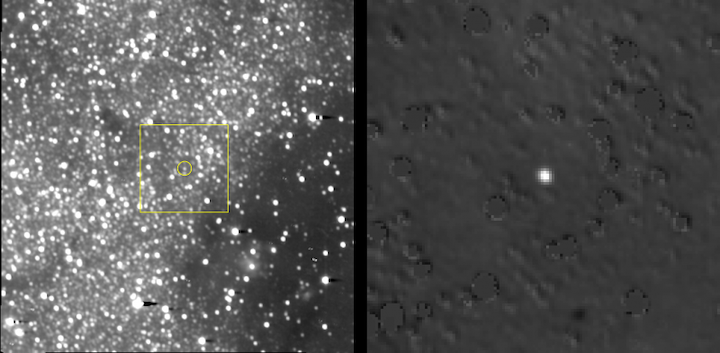

The figure on the left is a composite image produced by adding 48 different exposures from the News Horizons Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), each with an exposure time of 29.967 seconds, taken on Aug. 16, 2018. The predicted position of the Kuiper Belt object nicknamed Ultima Thule is at the center of the yellow box, and is indicated by the yellow crosshairs, just above and left of a nearby star that is approximately 17 times brighter than Ultima.

At right is a magnified view of the region in the yellow box, after subtraction of a background star field "template" taken by LORRI in September 2017 before it could detect the object itself. Ultima is clearly detected in this star-subtracted image and is very close to where scientists predicted, indicating to the team that New Horizons is being targeted in the right direction. The many artifacts in the star-subtracted image are caused either by small mis-registrations between the new LORRI images and the template, or by intrinsic brightness variations of the stars. At the time of these observations, Ultima Thule was 107 million miles (172 million kilometers) from the New Horizons spacecraft and 4 billion miles (6.5 billion kilometers) from the Sun.

Image credits: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

-

Mission team members were thrilled – if not a little surprised – that New Horizons' telescopic Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) was able to see the small, dim object while still more than 100 million miles away, and against a dense background of stars. Taken Aug. 16 and transmitted home through NASA's Deep Space Network over the following days, the set of 48 images marked the team's first attempt to find Ultima with the spacecraft's own cameras.

"The image field is extremely rich with background stars, which makes it difficult to detect faint objects," said Hal Weaver, New Horizons project scientist and LORRI principal investigator from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. "It really is like finding a needle in a haystack. In these first images, Ultima appears only as a bump on the side of a background star that's roughly 17 times brighter, but Ultima will be getting brighter – and easier to see – as the spacecraft gets closer."

This first detection is important because the observations New Horizons makes of Ultima over the next four months will help the mission team refine the spacecraft's course toward a closest approach to Ultima, at 12:33 a.m. EST on Jan. 1, 2019. That Ultima was where mission scientists expected it to be – in precisely the spot they predicted, using data gathered by the Hubble Space Telescope – indicates the team already has a good idea of Ultima's orbit.

The Ultima flyby will be the first-ever close-up exploration of a small Kuiper Belt object and the farthest exploration of any planetary body in history, shattering the record New Horizons itself set at Pluto in July 2015 by about 1 billion miles. These images are also the most distant from the Sun ever taken, breaking the record set by Voyager 1's "Pale Blue Dot" image of Earth taken in 1990. (New Horizons set the record for the most distant image from Earth in December 2017.)

"Our team worked hard to determine if Ultima was detected by LORRI at such a great distance, and the result is a clear yes," said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. "We now have Ultima in our sights from much farther out than once thought possible. We are on Ultima's doorstep, and an amazing exploration awaits!"

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 28.11.2018

.

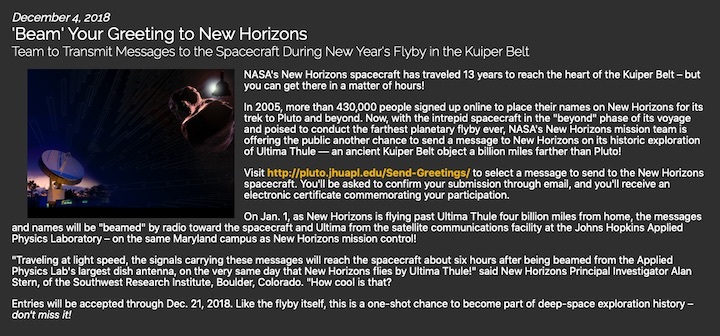

The PI's Perspective: Share the News - The Farthest Exploration of Worlds in History is Beginning

Spend your New Year's Eve with NASA, as New Horizons conducts the first close-up exploration of any Kuiper Belt object and the farthest exploration of any worlds in space ever attempted - more than 4 billion miles from Earth and a billion miles beyond Pluto!

The New Horizons spacecraft is healthy and is now beginning its final approach to explore Ultima Thule - our first Kuiper Belt object (KBO) flyby target - about a billion miles beyond Pluto. And on New Year's Eve and New Year's Day, New Horizons will swoop three times closer to "Ultima" than we flew past Pluto three years ago!

As someone who follows New Horizons, let your friends and social media followers know about the upcoming exploration of Ultima and that New Horizons and NASA will make history at the holidays with this epic exploration.

Ultima is 100 times smaller than Pluto, but its scientific value is incalculable. From everything we know, it was formed 4.5 or 4.6 billion years ago, 4 billion miles from the Sun.

It's been stored at that enormous distance from the Sun, at a temperature of nearly absolute zero, ever since, so it likely represents the best sample of the ancient solar nebula ever studied. Nothing like it has ever been explored.

Its geology and composition should teach us a lot about how these building blocks of small planets like Pluto were formed. The New Horizons mission team is excited too, and we can't wait to see what we will find!

Will Ultima be an agglomeration of still smaller bodies formed at the birth of the solar system? Will it have an atmosphere? Will it have rings? Will it have moons? Any of that could be possible, and soon we'll know the answers to these questions. So come along with New Horizons, spend your Christmas in the Kuiper Belt and your New Year's with NASA - and join us for the Ultima flyby.

Until then, I hope you'll always keep exploring - just as we do!

Quelle: SD, NASA

----

Update: 4.12.2018

.

12 years after launch, New Horizons probe zeroes in on mysterious Ultima Thule

Act Two of the 12-year-old New Horizons mission to Pluto and the solar system’s icy Kuiper Belt is heating up, with less than a month to go before NASA’s piano-sized spacecraft makes history’s farthest-out close encounter with a celestial object.

The New Year’s flyby of a mysterious Kuiper Belt object (or objects) known as Ultima Thule (UL-ti-ma THOO-lee) follows up on the mission’s first act, which hit a climax three years ago with a history-making flyby of Pluto.

Launched in 2006, New Horizons was never meant to be a one-shot deal. Even before the Pluto flyby, mission managers used the Hubble Space Telescope to identify its next quarry, a billion miles farther out in the Kuiper Belt. Now it’s crunch time for New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern and his team.

Again.

“This flyby is a lot harder than Pluto,” Stern said. “Ultima is tiny, and faint, much harder to navigate on. … Another difficulty, or challenge, really, is that we’re farther away, and that means communication times are longer. Bit rates are lower.”

Today the team beamed out commands to fine-tune New Horizons’ trajectory using the spacecraft’s navigational thrusters (which, by the way, were built at Aerojet Rocketdyne’s facility in Redmond, Wash.). It took more than six hours for the commands to reach the probe at the speed of light, at a rate of 1,000 bits per second.

By the time mission managers get confirmation that their commands have been executed (or not), New Horizons will have traveled hundreds of thousands of miles farther on its path (or off its path).

“It’s a one-shot, ‘get it right or go home’ deal, because there’s no U-turn to go back and have a re-do. … You have to plan every chess move with the spacecraft more carefully,” said Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute.

Dozens of scientists and engineers are due to converge on Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland to get set for the flyby, which is scheduled to come closest to Ultima Thule at 12:33 a.m. ET Jan. 1 (9:33 p.m. PT Dec. 31).

If all goes according to plan, New Horizons will pass by Ultima at a distance of 2,200 miles, or less than a third of the distance used for the Pluto flyby, But the mission team is on the watch for any mini-moons that would force a shift to a safer, more distant trajectory.

During a recent rehearsal, the team had to cope with a worst-case scenario in which New Horizons spotted 11 satellites in Ultima’s vicinity. “It was just flying into a hornet’s nest,” Stern recalled.

Neither Stern nor anyone else knows exactly what New Horizons will actually see.

“We don’t know what a primordial, ancient, perfectly preserved object like Ultima is, because no one’s ever been to something like this,” Stern explained. “It’s terra incognita. It is pure exploration. We’ll just see what it’s all about — if it’s got rings, if it’s got a swarm of satellites.”

The Hubble imagery suggests that Ultima Thule (also known as 2014 MU69) measures roughly 20 miles wide — and might consist of two or more mutually orbiting objects. The dearth of knowledge leaves plenty of room for surprises.

“Considering how much we knew about Pluto, and how much it astounded us, here we’re starting from complete scratch,” Stern said. “We barely know its size and its color. We can’t tell you anything about its composition or its atmosphere, or satellites, any of that. But we’re going to find out.”

To find out, the plutonium-powered New Horizons probe will employ the same suite of scientific instruments that worked so well to study Pluto and its moons more than three years earlier.

New Horizons’ long-range camera, known as LORRI, currently sees Ultima as a mere speck, but it should be able to make out its shape starting a few days before the flyby. During the closest phase of the encounter, LORRI could detect features as small as the boats floating on the lake in New York’s Central Park, Stern said.

New Horizons will make use of an ultraviolet imager called Alice and an infrared and visible-light imaging spectrometer called Ralph to characterize Ultima’s composition. A radio science experiment will take its temperature, and other instruments will analyze particles in Ultima’s cosmic neighborhood.

It’s likely to take months to send back all the data from the Ultima flyby, just as it did in the wake of 2015’s Pluto flyby. But eventually, Act Two of the New Horizons mission is expected to add to Act One’s already-substantial record of revelations about the icy worlds on the solar system’s edge.

Will there be an Act Three? Stern said he and his colleagues fully intend to ask NASA for another mission extension once Ultima is behind them.

He noted that at its current speed, New Horizons will be flying through the Kuiper Belt for almost a decade longer.

“We’re going to look for another flyby target, and we’re going to continue to observe Kuiper Belt objects with the telescopes on board,” he said. “If NASA approves that, there will be a third act.”

Quelle: GeekWire

----

Update: 9.12.2018

.

On Target: Record Setting Course-Correction Puts New Horizons on Track to Kuiper Belt Flyby

With just 29 days to go before making space exploration history, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft performed a short but record-setting course-correction maneuver on Dec. 2 that refined its path toward Ultima Thule, the Kuiper Belt object it will fly by on Jan. 1.

Just as the exploration of Ultima Thule will be the farthest-ever flyby of a planetary body, Sunday's maneuver was the most distant trajectory correction ever made. At 8:55 a.m. EST, New Horizons fired its small thrusters for 105 seconds, adjusting its velocity by just over 1 meter per second, or about 2.2 miles per hour. Data from the spacecraft confirming the successful maneuver reached the New Horizons Mission Operations Center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, through NASA's Deep Space Network, at 5:15 p.m. EST.

The maneuver was designed to keep New Horizons on track toward its ideal arrival time and closest distance to Ultima, just 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) at 12:33 a.m. EST on Jan. 1.

At the time of the burn New Horizons was 4.03 billon miles (6.48 billion kilometers) from Earth and just 40 million miles (64 million kilometers) from Ultima – less than half the distance between Earth and the Sun. From that far away, the radio signals carrying data from the spacecraft needed six hours, at light speed, to reach home.

The team is analyzing whether to conduct up to three other course-correction maneuvers to home in on Ultima Thule. +++

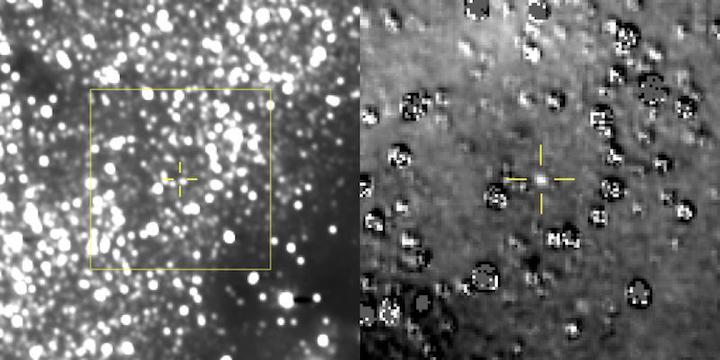

Ultima Comes into Clearer View: This composite image of Ultima Thule was taken just 33 hours before the Dec. 2 course-correction maneuver that fine-tuned New Horizons' trajectory for its New Year's flyby. At left is the full Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) image (an average of 10 individual 30-second exposures) with a yellow circle centered on the location of Ultima Thule. Unlike the LORRI images taken in August through October, Ultima is now evident among the many background stars even without further processing. Nevertheless, Ultima really stands out after subtracting the background stars; the region within the yellow box has been expanded in the star-subtracted version of the image on the right (many artifacts from the imperfect star subtractions are visible in this difference image).

Ultima was 4.01 billion miles (6.47 billion kilometers) from the Sun and 24 million miles (38.7 million kilometers) from the New Horizons spacecraft when the images were taken. "As the New Horizons spacecraft closes in on its target, Ultima Thule is getting brighter and brighter in the LORRI optical navigation images," said Hal Weaver, New Horizons project scientist from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. "It's now standing out much more clearly among the sea of background stars."

Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 19.12.2018

.

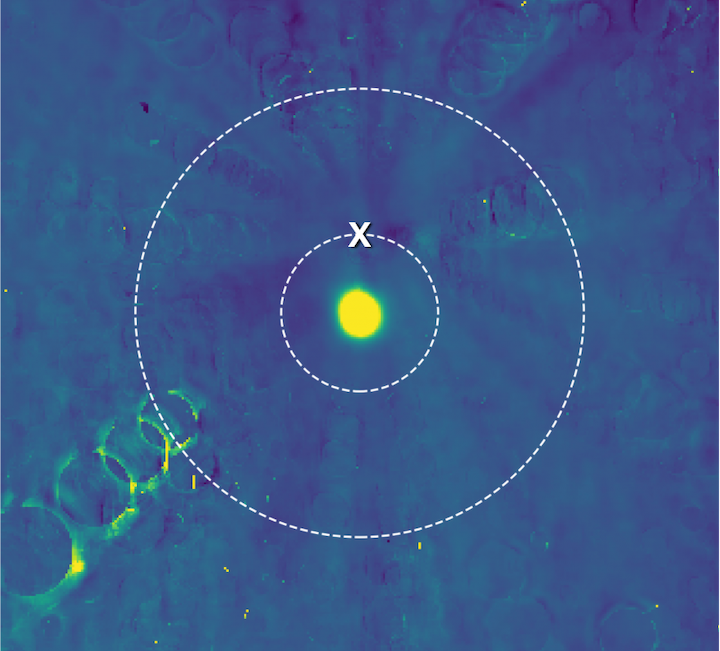

NASA's New Horizons Spacecraft Takes the Inside Course to Ultima Thule

Mission Team Sees No Moons or Rings Near Ultima, Opts for Primary Flyby Path

This image was made by combining hundreds images taken between August and mid-December by New Horizons' Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI). It has been colored using deep blue for the darkest regions and yellow for the brightest. Ultima Thule is the bright yellow spot in the middle. The two possible flyby distances for New Horizons are indicated by the two concentric circles. The mission has decided to fly along the closer path, toward the target point marked by an X. Individual images contain many background stars, but by combining images taken at different distances from Ultima Thule, most of the stars can be identified and removed. However, some of them leave behind traces, which can be seen as faint circles radiating away from the target point. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

With no apparent hazards in its way, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft has been given a "go" to stay on its optimal path to Ultima Thule as it speeds closer to a Jan. 1 flyby of the Kuiper Belt object a billion miles beyond Pluto – the farthest planetary flyby in history.

After almost three weeks of sensitive searches for rings, small moons and other potential hazards around the object, New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern gave the "all clear" for the spacecraft to remain on a path that takes it about 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) from Ultima, instead of a hazard-avoiding detour that would have pushed it three times farther out. With New Horizons blazing though space at some 31,500 miles (50,700 kilometers) per hour, a particle as small as a grain of rice could be lethal to the piano-sized probe.

The dozen-member New Horizons hazard watch team had been using the spacecraft's most powerful telescopic camera, the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), to look for potential hazards. The decision on whether to keep New Horizons on its original course or divert to a more distant flyby, which would have produced less-detailed data, had to be made this week since the last opportunity to maneuver the spacecraft onto another trajectory was today (Dec. 18).

New Horizons formed its hazard watch team in 2011 to prepare for its Pluto flyby, addressing concerns that Pluto's newly discovered small moons could spread dangerous debris across New Horizons' path. An intense search turned up no potential mission-ending risks; the team opted for the original flight plan and New Horizons safely carried out its historic exploration of the Pluto system in July 2015.

This year, the hazard watch team has been conducting similar analyses on the approach to Ultima Thule, which is officially designated 2014 MU69. Any ring structure reflecting even just five 10-millionths of the sunlight falling on it would have been visible in the images, as would any moons more than about two miles (three kilometers) across, but the team saw none. Scientists will continue to look for rings or moons that are very close to Ultima, but those would not pose a risk.

"Our team feels like we have been riding along with the spacecraft, as if we were mariners perched on the crow's nest of a ship, looking out for dangers ahead," said hazards team lead Mark Showalter, of the SETI Institute. "The team was in complete consensus that the spacecraft should remain on the closer trajectory, and mission leadership adopted our recommendation."

"The spacecraft is now targeted for the optimal flyby, over three times closer than we flew to Pluto," added Stern. "Ultima, here we come!"

New Horizons will make its historic close approach to Ultima Thule at 12:33 a.m. EST on Jan. 1 — the first ever flyby of a Kuiper Belt object.

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, designed, built, and operates the New Horizons spacecraft, and manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. The Southwest Research Institute, based in San Antonio, leads the science team, payload operations and encounter science planning. New Horizons is part of the New Frontiers Program managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 23.12.2018

.

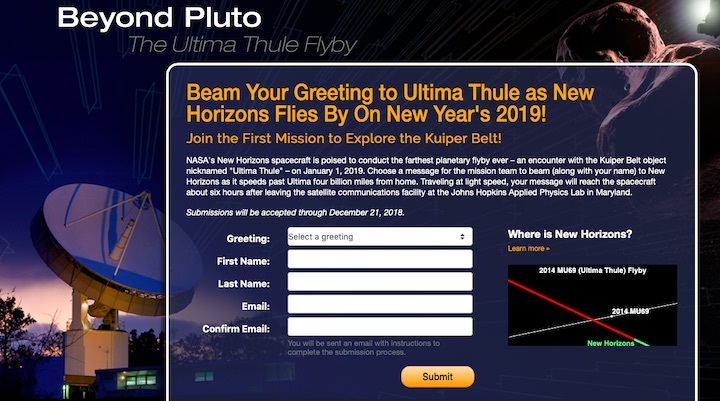

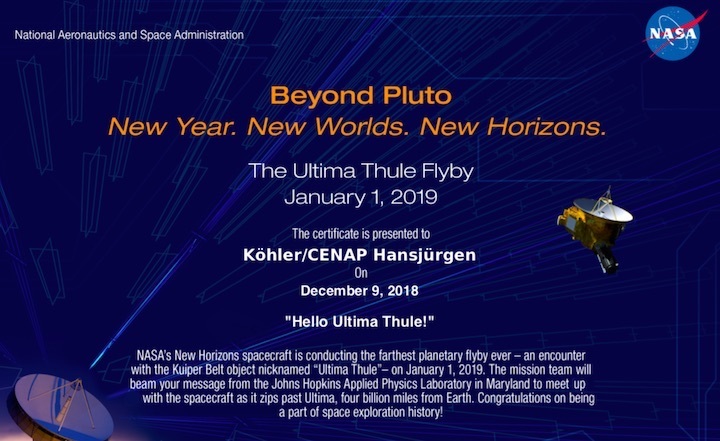

CENAP "Beam" Greeting to New Horizons

Quelle: CENAP-Archiv

+++

Wink of a Star

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Y_qc8Ifhso&feature=youtu.be

NASA’s New Horizons team trained mobile telescopes on an unnamed star (circled) from a remote area of Argentina on July 17, 2017. A Kuiper Belt object 4.1 billion miles from Earth -- known as 2014 MU69 -- briefly blocked the light from the background star, in what’s known as an occultation.

-

Ultima Thule's First Mystery

New Horizons scientists puzzled by lack of a 'light curve' from their Kuiper Belt flyby target

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft is bearing down on Ultima Thule, its New Year's flyby target in the far away Kuiper Belt. Among its approach observations over the past three months, the spacecraft has been taking hundreds of images to measure Ultima's brightness and how it varies as the object rotates.

Those measurements have produced the mission's first mystery about Ultima. Even though scientists determined in 2017 that the Kuiper Belt object isn't shaped like a sphere – that it is probably elongated or maybe even two objects – they haven't seen the repeated pulsations in brightness that they'd expect from a rotating object of that shape. The periodic variation in brightness during every rotation produces what scientists refer to as a light curve.

"It's really a puzzle," said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute. "I call this Ultima's first puzzle – why does it have such a tiny light curve that we can't even detect it? I expect the detailed flyby images coming soon to give us many more mysteries, but I did not expect this, and so soon."

What could explain the tiny, still undetected light curve? New Horizons science team members have different ideas.

"It's possible that Ultima's rotation pole is aimed right at or close to the spacecraft," said Marc Buie, also of the Southwest Research Institute. That explanation is a natural, he said, but it requires the special circumstance of a particular orientation of Ultima.

"Another explanation," said the SETI Institute's Mark Showalter, "is that Ultima may be surrounded by a cloud of dust that obscures its light curve, much the way a comet's coma often overwhelms the light reflected by its central nucleus." That explanation is plausible, Showalter added, but such a coma would require some source of heat to generate, and Ultima is too far away for the Sun's feeble light to do the trick.

"An even more bizarre scenario is one in which Ultima is surrounded by many tiny tumbling moons," said University of Virginia's Anne Verbiscer, a New Horizons assistant project scientist. "If each moon has its own light curve, then together they could create a jumbled superposition of light curves that make it look to New Horizons like Ultima has a small light curve." While that explanation is also plausible, she adds, it has no parallel in all the other bodies of our solar system.

So, what's the answer?

"It's hard to say which of these ideas is right," Stern said. "Perhaps its even something we haven't even thought of. In any case, we'll get to the bottom of this puzzle soon – New Horizons will swoop over Ultima and take high-resolution images on Dec. 31 and Jan. 1, and the first of those images will be available on Earth just a day later. When we see those high--resolution images, we'll know the answer to Ultima's vexing, first puzzle. Stay tuned!"

Quelle: NASA

+++

New Horizons Notebook: On Ultima's Doorstep

Final Maneuver Guides New Horizons Precisely to Ultima

New Horizons carried out its last trajectory correction maneuver on approach to Ultima Thule last week, a short thruster burst to direct the spacecraft closer to its precise flyby aim point just 2,200 miles (3,500) above the mysterious Kuiper Belt object at 12:33 am EST on Jan. 1.

At 7:53 a.m. EST on Dec. 18, New Horizons fired its small thrusters for just 27 seconds, a 0.26 meter-per-second adjustment that corrected about 180 miles (300 kilometers) of estimated targeting error and sped up the arrival time at Ultima by about five seconds. Data from the spacecraft confirming the successful maneuver reached the New Horizons Mission Operations Center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, through NASA's Deep Space Network, at 4:34 p.m. EST the same day.

"From mission design to navigation to operations, this entire team worked very hard to get the spacecraft where it needs to be for this historic exploration in the Kuiper Belt," said Alice Bowman, New Horizons mission operations manager from APL. "After guiding New Horizons for 13 years and more than four billion miles, we are poised to conduct the farthest flyby in history and reveal a new world."

The maneuver was the farthest spacecraft course correction ever conducted, carried out while New Horizons was about 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion kilometers) from Earth. At that distance a radio signal from the spacecraft – traveling at light speed -- needs just over 6 hours to reach home.

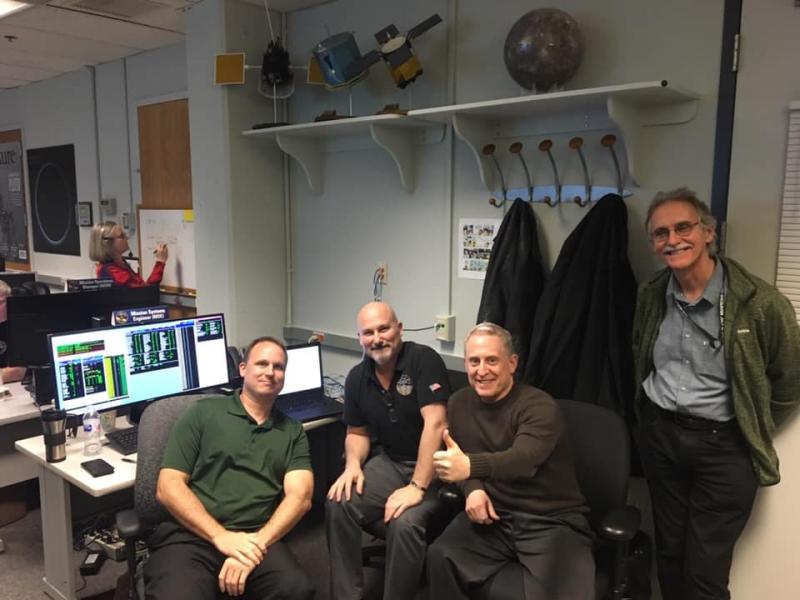

On Dec. 18, in the Mission Operations Center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, flight controllers Becca Sepan (left) and Katie Bechtold await word of a successful course correction from the New Horizons spacecraft. (Credit: Alan Stern)

From left, Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman charts the results of the trajectory correction maneuver as Gabe Rogers (deputy mission systems engineer), Chris Hersman (mission systems engineer), Alan Stern (principal investigator) and John Spencer (deputy project scientist) confirm the maneuver's success. (Image provided by Alan Stern)

Good Luck New Horizons!

Many friends of the mission are wishing New Horizons good luck for its flyby at Ultima! Watch these greetings from Bill Nye and Chris Pratt

The Deep-Imaging Difference: Ultima Grows Brighter as New Horizons Approaches

After almost three weeks of sensitive searches for rings, small moons and other potential hazards around Ultima Thule – and seeing none –New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern opted last week for the project to remain on a path that takes it about 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) from Ultima, instead of a hazard-avoiding detour that would have pushed it three times farther out.

The dozen-member New Horizons hazard watch team used the spacecraft's most powerful telescopic camera, the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), to look for potential hazards. Examples of some of the images the team used to conduct its "deep" searches are below.

As seen from the spacecraft, Ultima Thule (officially named 2014 MU69) appears to be in the constellation of Sagittarius, hovering in front of the heart of the Milky Way, not far from the central plane of our galaxy. The image field is filled with stars in the most crowded and rich area of the sky.

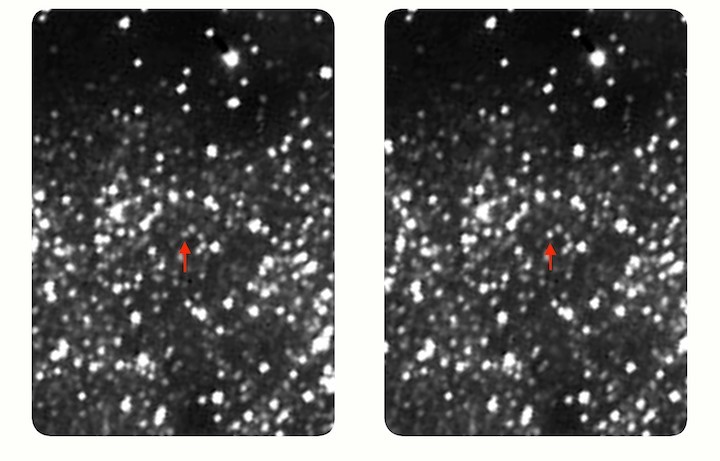

Each half of this stereo pair of images — created from LORRI images by astrophysicist and New Horizons science team collaborator Dr. Brian May — represents a combination of several dozen images taken to search for faint companions, rings and dust clouds around Ultima.

The first sequence was taken on Dec. 6, when New Horizons was approximately 19,963,400 miles (32,128,000 kilometers) from Ultima. It includes 61 images of 30 about seconds each, for a total exposure time of about 30 minutes.

The second sequence was obtained a week later, on Dec. 13, when New Horizons had closed to within 14,638,880 miles (about 23,559,000 kilometers) of Ultima. It contains 40 30-second images, totaling 20 minutes of total exposure.

The arrow marks the location of Ultima Thule in each sequence.

Each half of this stereo pair of images — created from LORRI images by astrophysicist and New Horizons science team collaborator Dr. Brian May — represents a combination of several dozen images taken to search for faint companions, rings and dust clouds around Ultima.

The first sequence was taken on Dec. 6, when New Horizons was approximately 19,963,400 miles (32,128,000 kilometers) from Ultima. It includes 61 images of 30 about seconds each, for a total exposure time of about 30 minutes.

The second sequence was obtained a week later, on Dec. 13, when New Horizons had closed to within 14,638,880 miles (about 23,559,000 kilometers) of Ultima. It contains 40 30-second images, totaling 20 minutes of total exposure.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 27.12.2018

.

December 26, 2018All About Ultima: New Horizons Flyby Target is Unlike Anything Explored in Space

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft is set to fly by a distant "worldlet" 4 billion miles from the Sun in just six days, on New Year's Day 2019. The target, officially designated 2014 MU69, was nicknamed "Ultima Thule," a Latin phrase meaning "a place beyond the known world," after a public call for name recommendations. No spacecraft has ever explored such a distant world.

This is the first detection of Ultima Thule using the highest resolution mode of the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) aboard the New Horizons spacecraft. Three separate images, each with an exposure time of 0.5 seconds, were combined to produce the image. All three images were taken on Dec. 24, when Ultima was 4 billion miles (6.5 billion kilometers) from the Sun and 6.3 million miles (10 million kilometers) from the New Horizons spacecraft.(Click for full caption)

Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Ultima, as the flyby target is affectionately called by the New Horizons team, is orbiting in the heart of our solar system's Kuiper Belt, far beyond Neptune. The Kuiper Belt — a collection of icy bodies ranging in size from dwarf planets like Pluto to smaller planetesimals like Ultima Thule (pronounced "ultima toolee") and even smaller bodies like comets — are believed to be the building blocks of planets.

Ultima's nearly circular orbit indicates it originated at its current distance from the Sun. Scientists find its birthplace important for two reasons. First, because that means Ultima is an ancient sample of this distant portion of the solar system. Second, because temperatures this far from the Sun are barely above absolute zero — mummifying temperatures that preserves Kuiper Belt objects — they are essentially time capsules of the ancient past.

Marc Buie, New Horizons co-investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, and members of the New Horizons science team discovered Ultima using the Hubble Space Telescope in 2014. The object is so far and faint in all telescopes, little is known about the world beyond its location and orbit. In 2016, researchers determined it had a red color. In 2017, a NASA campaign using ground-based telescopes traced out its size — just about 20 miles (30 kilometers) across — and irregular shape when it passed in front of a star, an event called a "stellar occultation."

From its brightness and size, New Horizons team members have calculated Ultima's reflectivity, which is only about 10 percent, or about as dark as garden dirt. Beyond that, nothing else is known about it — basic facts like its rotational period and whether or not it has moons are unknown.

"All that is about to dramatically change on New Year's Eve and New Year's Day," said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, also of SwRI. "New Horizons will map Ultima, map its surface composition, determine how many moons it has and find out if it has rings or even an atmosphere. It will make other studies, too, such as measuring Ultima's temperature and perhaps even its mass. In the space of one 72-hour period, Ultima will be transformed from a pinpoint of light — a dot in the distance — to a fully explored world. It should be breathtaking!"

"New Horizons is performing observations at the frontier of planetary science," said Project Scientist Hal Weaver, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, "and the entire team looks forward to unveiling the most distant and pristine object ever explored during a spacecraft flyby."

"From Ultima's orbit, we know that it is the most primordial object ever explored. I'm excited to see the surface features of this small world, particularly the craters on the surface," said Deputy Project Scientist Cathy Olkin, of SwRI. "Young craters could provide a window to see the composition of the subsurface of Ultima. Also by counting the number and impactors that have hit Ultima, we can learn about the number of small objects in the outer solar system."

The New Horizons spacecraft is on course to fly by Ultima on New Year's Day, Jan. 1, at 12:33 a.m. EST.

The Kuiper Belt lies in the so-called "third zone" of our solar system, beyond the terrestrial planets (inner zone) and gas giants (middle zone). This vast region contains billions of objects, including comets, dwarf planets like Pluto and "planetesimals" like Ultima Thule. The objects in this region are believed to be frozen in time — relics left over from the formation of the solar system.

Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

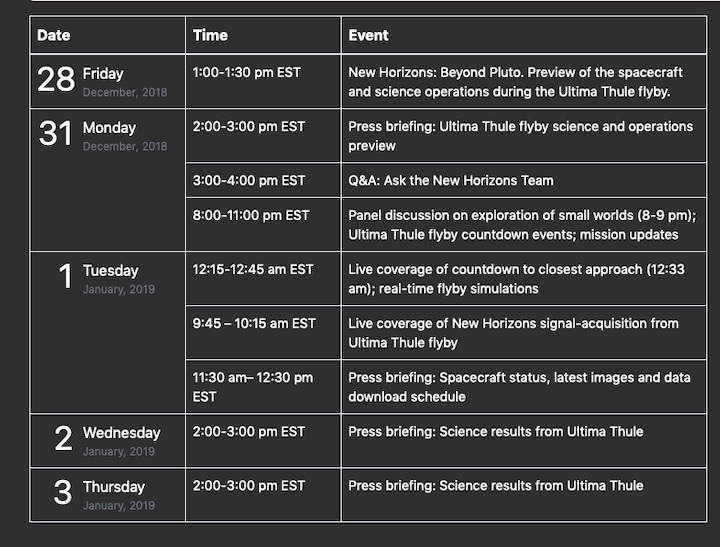

NASA-TV:

Quelle: NASA