-

24.11.2012

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Quelle: Mars One

.

Update: 11.12.2013

.

1,058 People Are Serious About Living on Mars Until They Die

.

In its highly publicized search to find people for a private manned mission to the Red Planet, Mars One has winnowed down its applicant pool of 200,000 to 1,058 candidates — all of whom are serious about living out out the rest of their lives on another planet.

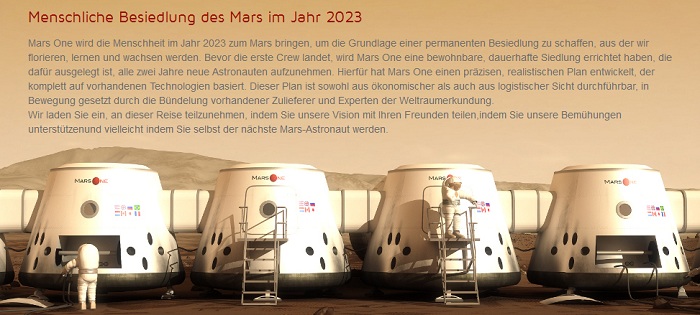

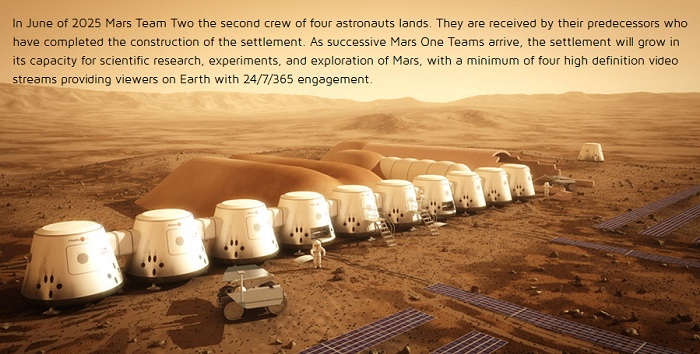

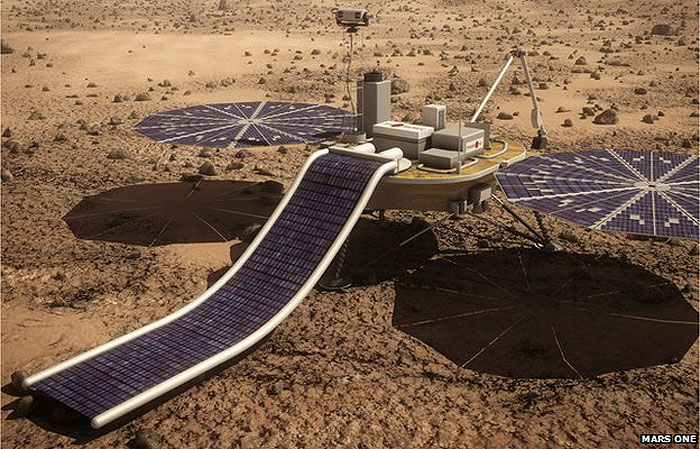

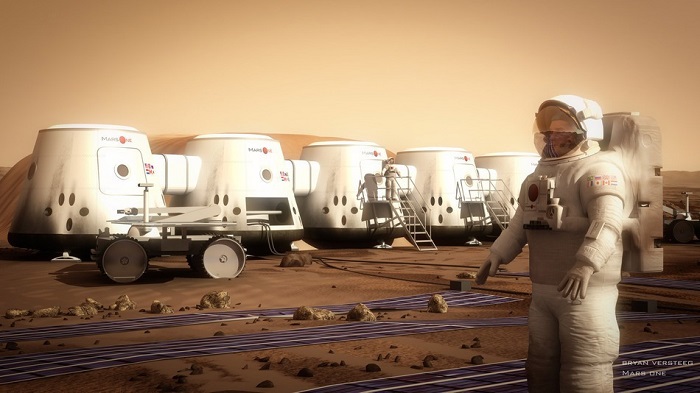

Headed up by Dutch entrepreneur Bas Lansdorp, Mars One, which claims to be a non-profit entity, plans to launch a one-way mission to Mars. Lansdorp says he can put a permanent crew of six on our neighboring planet by 2023, and he will continue to shuttle more settlers every few years. The colony would be outfitted with livable habitats, greenhouses, rovers and everything else a human would need to survive on an oxygen-free, resourceless dust bowl. There's only one requirement: You must be at least 18 years old.

To say something like this would be astronomically expensive is only a small chip of the giant iceberg of issues — technical hurdles, health concerns, legal obstacles — Lansdorp will have to face in order to make a Mars One mission successful. By his calculations, Lansdorp needs $6 billion for the first mission — and he has a business plan to make this happen.

Lansdorp, a businessman who founded a wind energy company, believes Mars One will be the greatest reality television show the world has ever seen. Every second of this venture will be filmed, and Lansdorp is banking on the fact that advertisers with deep pockets won't hesitate to pull out their checkbooks for a piece of history. When I spoke with him at a press conference in New York earlier this year, Lansdorp pointed to the Olympics as an example: "Four billion dollars for four weeks, just because the world is watching," he told me.

The lives of these future astronauts are solely in the hands of advertisers. But what happens when Mars One jumps the shark? What happens when humans on Mars is old news, and no one is watching? Who will pay the billions upon billions needed to sustain these people until they die?It's all part of the risk. Which brings me to my next point: Who would apply for something like this? More than 200,000 people from all walks of life. However, this second round tells us more about who they really are. Of the 1,058 candidates moving on, 586 are male, and 472 are female. The United States has the most participants, with 297. Canada follows with 75, India with 62 and Russia with 52. The rest are scattered across the globe, from Italy to Singapore.

The majority are educated: 347 hold a Bachelor's degree, 159 have a Master's and 29 even have an M.D. Most (813) are employed, but 164 are still in school. Most of the applicants are under 36.

These people will now undergo medical examination and several selection phases that include "rigorous simulations, many in team settings, with focus on testing the physical and emotional capabilities of our remaining candidates," according to Mars One's chief medical officer, Norbert Kraft.

While there are no real requirements — other than age — for a Mars One astronaut, Kraft told me in January that he will look for people who can work well together. The crew will be mixed gender, and they will all need to speak English. Besides that, they'll learn most of the skills they need to survive in training for the next eight years or so.

But despite the physical and mental tests Mars One applicants will go through off screen, the selection isn't up to the appointed experts — it's up to us.

The public will choose the candidates who make it to the final round after a televised gameshow-like reality competition. Up to 40 applicants per country will participate in challenges "that demonstrate their suitability to become one of the first humans on Mars." The audience will select the one applicant from their respective country that will move forward.

Mars One reserves the right to pick the final crew, but if everything hinges on advertising dollars, you better believe those people will be appealing to audiences. They'll have to be marketable.

If we're getting serious about it, Mars One has a very small chance of sending humans to Mars in 10 years for $6 billion. (For reference, NASA's Curiosity rover cost $2 billion.) Lansdorp has received some funding from Lockheed-Martin, but he has repeatedly said he will not partner with federal space agencies like NASA to make this happen. He also claims he'll use SpaceX technology, but a spokesperson from the company told me nothing is officially on the table.

But for all its flaws, Mars One is doing one thing right: People of all ages from all corners of the world are talking about space exploration again. And, let's face it, that's something we've needed for years.

Quelle: Mashable

.

Mars One Narrows List Of Wannabe Martians For 2025 Colony

A private company hoping to populate Mars has narrowed its applicant pool by 99.5 percent. Here's a by-the-numbers look at the remaining 1,058 applicants.

.

The number of Earthlings looking at a potential one-way ticket to Mars has just shrunk by 99.5 percent.

People started applying for a voyage to the red planet in April 2013 through Mars One, a Netherlands-based private venture that wants to land humans there by 2025. By the time the company stopped taking applications, more than 200,000 people had submitted one. Today, Mars One announced that it's made a short(er) list of 1,058 applicants.

Here's what the numbers tell us about Mars' potential future inhabitants::

- 55 percent of the new applicant pool is male and 45 percent is female. That's more masculine than the general population, but still substantially more gender balanced than U.S. Congress.

- 63 percent have a bachelor's degree or higher, while 3 percent of the total hold medical degrees (who wouldn't want a doctor on Mars?). Less than 7 percent of people on Earth in 2010 had college degrees, which means Mars may soon be the most educated planet in the solar system.

- 76 percent of applicants are employed, 15 percent are still in school, and 8 percent are unemployed. If surviving as a colonist on another planet counts as a job, expect Mars to have an employment rate of 100 percent.

- 43 percent of applicants come from the Americas, 27 percent from Europe, 21 percent from Asia, 5 percent from Africa, and 4 percent from Oceania. That hardly jibes with the distribution of the world population; if it did, 60 percent of Martians would be Asian and 14 percent would hail from the Americas. A closer match is the distribution of global wealth by nation, of which the Americas claim 35 percent.

- 107 countries are represented in the applicants and, at 28 percent of all those accepted into Mars One's second round, the United States has the largest pool of candidates.

- 34 percent of potential Martians are younger than 25, about 65 percent are between the ages of 26 and 55, and 2 percent are older than 56. In contrast, 40 percent of Earthlings are less than 25 years old and 17 percent older than 56.

The defining moment for Mars One will be selecting its crew (or crews) for a 2025 voyage, but the news does bring a private mission to the red planet one step closer to reality. A bigger step occurred earlier this month, when Mars One announced a contract with Lockheed Martin to craft a design concept for a robotic lander. Its goal: to find and prepare a landing site for the first human visitors to Mars.

Quelle: PS

.

Update: 1.01.2014

.

An East Sooke woman took one small step Monday toward fulfilling her lifelong dream of exploring outer space.

Marina Miral learned by email that she was one of 1,058 candidates short-listed for a one-way mission to Mars that aims to establish a human settlement on the red planet by 2025.

The Mars One project selected the 30-year-old author from more than 200,000 applicants around the world.

“I was shocked, for one, because I’d kind of given up; I sort of thought I would have heard sooner,” Miral said. “I just haven’t been able to stop smiling.

“I’m so excited. I’ve never been so excited.”

Miral first heard about the project last May, but delayed applying until just before the Aug. 31 deadline so that she could have more time to consider what she wanted to say.

There was never any doubt about putting her name forward. Miral said she has wanted to become an astronaut ever since she began watching Star Trek at age 10.

“This might sound a little bit silly, but my dream for my entire life was to go to Starfleet Academy,” she said. “But that is fictional, so it’s been pretty hard trying to find something that will substitute for that dream.”

She found her answer when Mars One, a Dutch non-profit foundation, began searching for astronauts in April.

The foundation expects to send its first four colonists to Mars at a cost of $6 billion. Officials plan to raise the money through sponsorships, donations, crowdfunding and the sale of broadcasting rights to every aspect of the mission from astronaut selection to landing.

Mars One co-founder Bas Lansdorp said in a statement Monday that the short list of potential astronauts offers the first “tangible glimpse” of what the Mars settlement will look like.

“The challenge with 200,000 applicants is separating those who we feel are physically and mentally adept to become human ambassadors on Mars from those who are obviously taking the mission much less seriously,” he said. “We even had a couple of applicants submit their videos in the nude!”

Miral said she’s unsure why she was selected.

“I tried to get across in my application just how important it was to me and that I was taking it seriously. So I think that was a big thing.

“I just love the idea of exploring, going somewhere completely new. Going to space — I can’t even describe how wonderful the thought is for me.”

Miral, who recently changed her last name from Miller, earns a living by writing juvenile fiction novels with her mother, Angela Dorsey. The pair co-author the Sun Catcher series of books.

Though torn by the one-way nature of the mission, Dorsey said her daughter is a perfect choice.

“She’s always dreamed of doing something like this, but she just never thought it was possible until this Mars One thing came along, right? It’s sort of an unusual life dream.”

Miral still has to make it through three more rounds in the selection process.

Mars One expects to pick its final candidates by the end of 2015. Up to 40 people will then spend the next seven years training to survive on Mars for the rest of their lives.

Quelle: Times Colonist

.

Why over 1,000 people are competing to go to Mars – and not come back

Mars One, the Dutch nonprofit planning to put a human colony on Mars in 2025, has whittled its applicant pool to about 1,000 people hoping to give up their Earthling-status, for good.

.

Mars One, the Dutch nonprofit planning to put a human colony on Mars in 2025, announced on Monday that it has whittled its applicant pool to about 1,000 applicants to be among the first astronauts to trade in their Earth citizenship for a – permanent – Martian residence.

The 1,058 Martian hopefuls, selected from about 200,000 original applicants, will go through several more application rounds before Mars One will select just 24 people for what is to the applicants the ultimate prize but is for others a nightmare of cosmic proportions: the chance to go live on Mars, with absolutely no chance of ever coming home.

“For people who don’t want to go to Mars, it’s almost unimaginable to them why anyone would want to go to Mars,” says Bas Lansdorp, co-founder and CEO of Mars One. “For people that do want to go to Mars, they can’t imagine that anyone wouldn’t be interested in going to Mars.”

“These people will never understand each other,” he says.

But Mr. Lansdorp is counting on the non-Mars-goers at least wanting to watch the Mars enthusiasts get to the Red Planet.

Mars One’s grand mission, which the nonprofit expects to cost about $6 billion, is expected to be financed in part from the sale of the broadcasting rights to air the foundation’s process: the future selection rounds, the hoped-for triumphant launch to Mars, and the probably dramatic saga of setting up home on the Red Planet. The idea is that Mars One’s venture, broadcast around the world, will be “everybody’s mission to Mars,” says Lansdorp.

At the moment, Mars One has offers from “two major TV studios” to buy those rights, he says, adding that the details of the coming selection rounds will be released after a contract is signed. Since it will take more than just television dollars to get the still sci-fi colony off the ground, Mars One is also in talks with a “major investment firm” and several corporations, Lansdorp says.

As Mars One’s funding scheme in large part depends on audiences and television ratings, its business model has often been called reality show-like in style. In the first application round over the summer, which drew 202,586 would-be Martians, some applicants had billed themselves as proverbial Adam and Eves, prepared to inaugurate a new human civilization, albeit in a thoroughly un-Eden-like world. Others, perhaps in the mocking gesture, or maybe in an attempt to appeal to reality show casting mentalities, made their pitches in nude videos.

But Mars One is less interested in reality show contestants than astronauts with the watchable-ness factor of Olympic athletes, says Lansdorp, who points to broadcasters’ revenue from televising the Olympic games as evidence for the feasibility of his business plan.

“In the Olympic games, we see extraordinary people do extraordinarily difficult things,” says Lansdorp. “We’re looking for the same type of people. We’re looking for serious applicants who want nothing more than to go to Mars."

And Mars One’s applicants are serious.

“The people who think that going to Mars would be a nightmare obviously aren’t volunteering,” says David King, 25, a craftsman based in Brooklyn, NY, and a second round applicant. “But there are people who want to go, and I’m one of those people. There are people willing to put themselves out there for the greater cause.”

The biggest percentage of Mars One’s second-round applicants are Americans, with others coming from Canada, India, Russia, and China. The contestants are overwhelmingly young, with more than 70 percent under 35 years old (the minimum age is 18). Almost all are employed or in school.

Above all, Mars One was scouting for applicants that appear capable of handling the possible mental trauma of spending their entire lives in confined spaces with just a small group of people from whom it will be impossible to escape, the foundation says.

“It’s important to be with people you can actually talk to and who you generally don’t want to kill,” says Lauren Reeves, 30, a comedian based in New York City who is among the short-listed applicants.

Ms. Reeves says that though she would be “sad to leave” Earth, she is fully committed to getting to Mars: “I would hate myself for saying no to it, for not being bold enough to go.”

Lansdorp, who has a girlfriend and a three-month-old son, is not among the applicants.

“I’m certainly not qualified,” he says. “I’m not able to be in a small group in a small space for a long period of time, without things escalating.”

Plus, “my girlfriend is very fond of Earth,” he says.

Mars One plans to announce its selected six teams of four astronauts in 2015, two years later than it had originally said it would. The astronauts will spend 10 years in training before the first team leaves Earth – for good – in 2024. The next team will follow two years later, and so on. If all goes well, Mars One will cull for more applications.

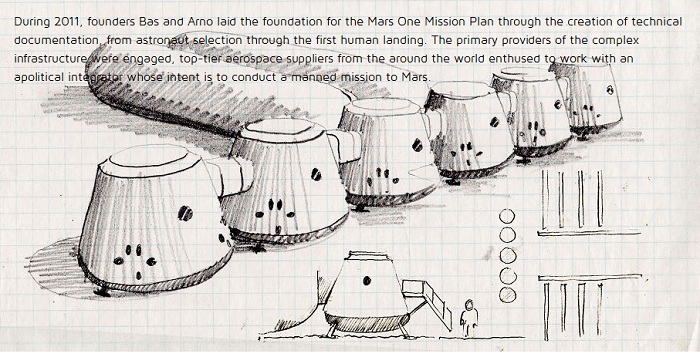

The first humans on Mars will live in inflatable domes, called “habitats.” To shield the residents from radiation, these domes will topped with several meters of soil. These enormous dirt piles are not shown in mockups of the prospective Martian colony, though, since “it makes the drawing very boring,” says Lansdorp. “It would be just a sand dune.”

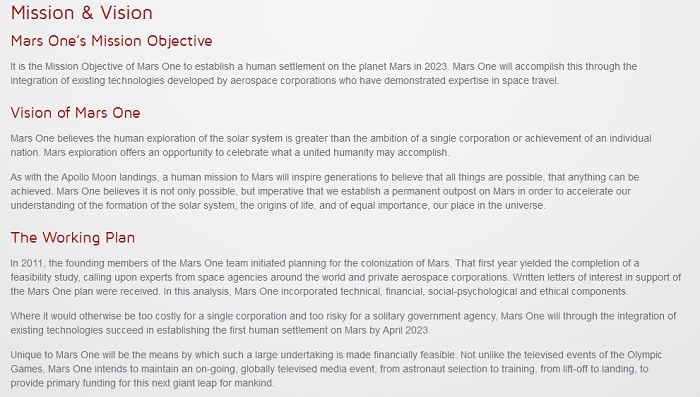

While Earth-bound audiences wait, and wait, to see inflatable domes on Mars, the foundation is offering another mission to watch. Earlier this month, the company signed contracts with aerospace companies Lockheed Martin Corp. and Surrey Satellites Technology to undertake concept studies for a 2018 mission to send an unmanned lander and orbiter to Mars.

The foundation has billed the 2018 mission, for which it is raising funds on Indiegogo, as a demonstration of capabilities to fulfill its bigger ambitions, a sort of proverbial stepping-stone in a great leap for prospective Martians.

“It’s very normal to be skeptical about a Dutch nonprofit that wants to get humans to Mars in 10 years,” says Lansdorp. “But we don’t see any hurdles that we believe cannot be overcome.”

“This is one of the great things that’s left to be done,” he says.

Quelle: C-Monitor

.

Update: 31.01.2014

.

.

Update: 31.03.2014

.

Mars One beginnt mit Arbeit an Simulations Mars Home für Crew-Mitglieder

.