22.11.2017

An observatory has been built under the auspices of Danish researchers to study the phenomenon of lightning in space

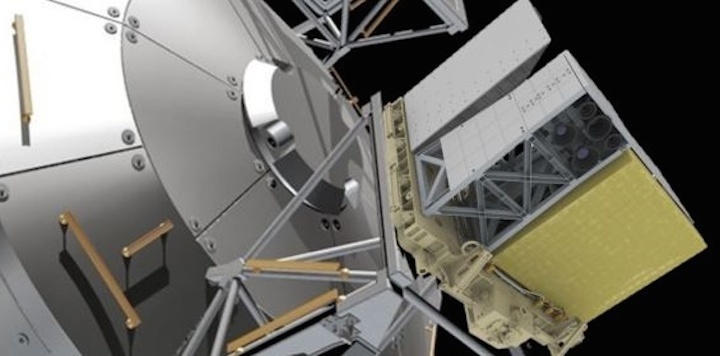

They say that lightning never strikes twice, but can it affect our climate? (graphic:ASIM)

-

In August 2015, when Denmark’s first astronaut Anders Mogensen spent time on the international space station ISS, one of the things that caught his attention was the lightning bursts visible in space.

These phenomena – called ‘red sprites’, ‘blue jets’, ‘haloes’ and ‘elves’ – were first discovered in 1989 and have since been of great interest to scientists and climate researchers.

Space is the place

After four years of development, a Danish-steered research consortium has constructed an advanced observatory called the Atmosphere-Space Interactions Monitor (ASIM). The observatory weighs 314 kilos and will be mounted on the ISS, reports DR Nyeheder.

“It’s always exciting when we in Denmark can be at the forefront when it comes to space travel and space exploration,” said Mogensen. “We definitely have the ability to contribute to the areas that we choose, and ASIM is a good example of this.”

An overlooked climatic factor?

The observatory is expected to be launched in the middle of March 2018, and when it is in place on the ISS, it will be able to observe and photograph lightning at an altitude of 80-90 kilometres.

As it stands today, nobody knows exactly how and why these lightning bursts occur. “And more importantly, we don’t know what influence they have on our atmosphere,” added Mogensen.

The height at which these lightning bursts take place shows there must be a way of exchanging gasses or molecules between the troposphere, which is the lower part of the atmosphere, and the stratosphere, which is the upper part.

“We don’t normally expect weather phenomena to occur in the stratosphere, but if you get water vapour up there, it can remain for a very long time,” continued Mogensen.

“Water vapour is a very strong greenhouse gas that can have a great effect on climate and our atmosphere, which we have perhaps not calculated into our existing climate models.”