20.11.2017

Stars that vary in brightness shine in the oral traditions of Aboriginal Australian

Aboriginal Australians have been observing the stars for more than 65,000 years, and many of their oral traditions have been recorded since colonisation. These traditions tell of all kinds of celestial events, such as the annual rising of stars, passing comets, eclipses of the Sun and Moon, auroral displays, and even meteorite impacts.

But new research, recently published in The Australian Journal of Anthropology, reveals that Aboriginal oral traditions describe the variable nature of three red-giant stars: Betelgeuse, Aldebaran and Antares.

This challenges the history of astronomy and tells us that Aboriginal Australians were even more careful observers of the night sky than they have been given credit for.

What is a variable star?

The Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote in 350BCE that the stars are unchanging and invariable. This was the position held by Western science for nearly 2,000 years.

It wasn’t until 1596 that this was proved wrong, when German astronomer David Fabricius showed that the star Mira (Omicron Ceti), in the constellation of Cetus, changed in brightness over time.

In the 1830s, astronomer John Herschel observed the relative brightness of a handful of stars in the sky. Over the course of four years, he noticed that the star Betelgeuse, in Orion, was sometimes fainter and sometimes brighter than some of the other stars. His discovery paved the way for an entire field of astrophysics dedicated to studying the variable nature of stars.

But was Herschel the first to recognise this?

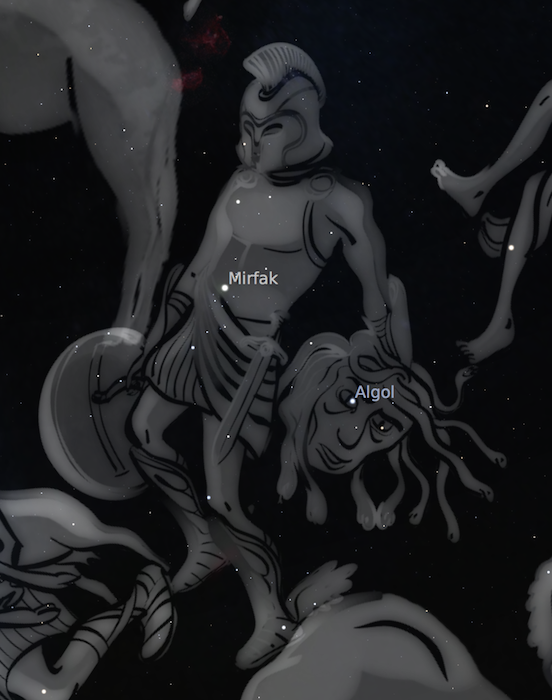

There is evidence that ancient Egyptians observed the variability of the star Algol (Omicron Persei).

Algol consists of two stars that orbit each other. As one moves in front of the other, it blocks the other star’s light, causing it to dim slightly. This is called an eclipsing binary. It can be seen in the sky as the winking eye of Medusa’s head in the Western constellation Perseus.

Are there any clear records from oral or Indigenous cultures that demonstrate knowledge of variable stars?

Emerging research reveals two Aboriginal traditions from South Australia that show the answer is a clear “yes”.

Nyeeruna and the protective Kambugudha

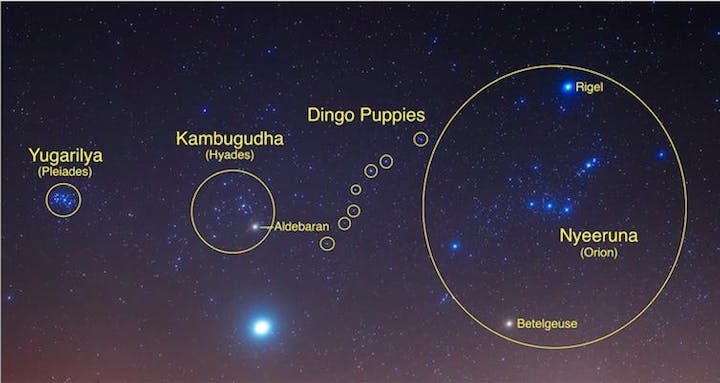

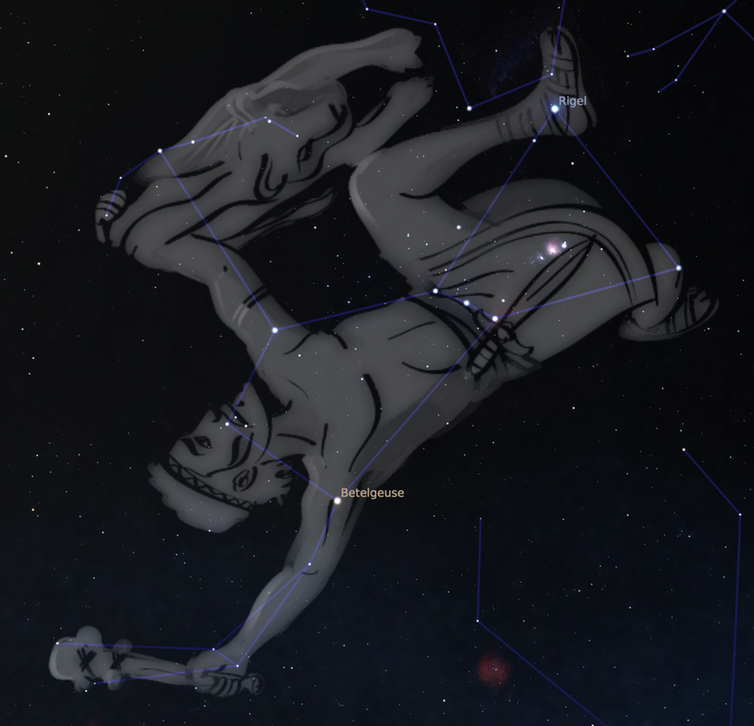

A Kokatha oral tradition from the Great Victoria Desert tells of Nyeeruna, a vain hunter who comprises the same stars, in the same orientation, as the Greek Orion.

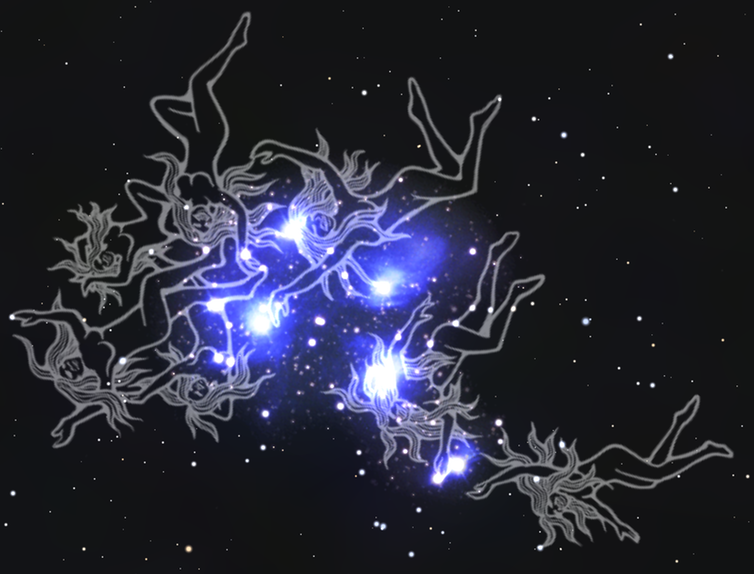

He is in love with the Yugarilya sisters of the Pleiades, but they are timid and shy away from his advances. Their eldest sister, Kambugudha (the Hyades star cluster), protects her younger sisters.

Nyreeuna creates fire-magic in his right hand (Betelgeuse) to overpower Kambugudha, so he can reach the sisters. She counters this with her own fire magic in her left foot (Aldebaran), which she uses to kick dust into Nyreeuna’s face. This humiliates Nyreeuna and his fire-magic dissipates.

Nyreeuna is persistent and replenishes his fire-magic again to get to the sisters. Kambugudha cannot generate hers in time, so she calls on Babba (the father dingo) for help. Babba fights Nyeeruna while Kambugudha and the other stars laugh at him, then places a row of dingo pups between them. This causes Nyeeruna much humiliation and his fire-magic dissipates again.

The story explains the variability of the stars Betelgeuse and Aldebaran. Trevor Leaman and I realised this in 2014, but we did not realise until now that the story also describes the relative periods of these changes.

Betelgeuse varies in brightness by one magnitude every 400 days, while Aldebaran varies by 0.2 magnitudes at irregular periods. The Aboriginal people recognised that Betelgeuse varies faster than Aldebaran, which is why they say that Kambugudha cannot generate her fire-magic in time to counter Nyreeuna.

Waiyungari and breaking sacred law

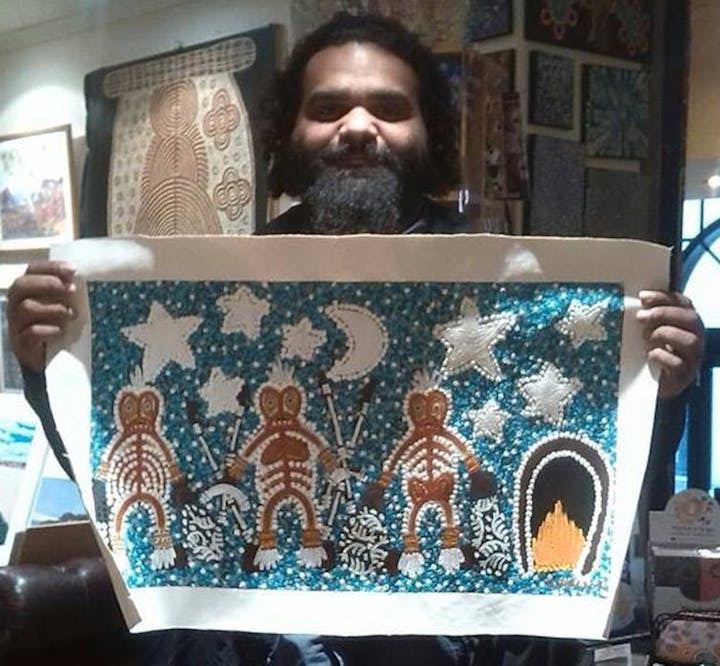

The second oral tradition comes from the Ngarrindjeri people, south of Adelaide. The story tells of Waiyungari, a young initiate who is covered in red ochre.

He is seen by two women, who find him very attractive. That night, they seduce him, which is strictly against the law for initiates. To escape punishment, they climb into the sky where Waiyungari becomes the star Antares and the women become the stars Tau and Sigma Scorpii, who flank him on either side.

The Ngarrindjeri people say Waiyungari signals the start of Spring (Riwuri) and occasionally gets brighter and hotter, symbolising his passion for the women. It is during this time that initiates must refrain from contact with the opposite sex. Antares is a variable star, which changes brightness by 1.3 magnitudes every 4.5 years.

What does this tell us?

Ruddy celestial objects hold special significance in Aboriginal traditions - from red stars to lunar eclipses to meteors - which may be one of the reasons why these stars are so significant.

Red objects are often related to fire, blood and passion. Psychological studies show that the colour red enhances sexual attraction between people, which may explain why both stories relate to sexual desire and taboos.

The Aboriginal traditions change the discovery timeline of these variable stars, which historians of astronomy say were discovered by Western scientists.

We see that Aboriginal people pay very close attention to subtle changes in nature, and incorporate this knowledge into their traditions. Astrophysicists have much to learn if we recognise the scientific achievements of Indigenous cultures and acknowledge the immense power of oral tradition.

+++

Kindred skies: ancient Greeks and Aboriginal Australians saw constellations in common

Look up on any clear night and you can see myriad stars, planets, and the Milky Way stretching across the sky. The chances are that you know some of the constellations.

The International Astronomical Union recognises 88 constellations, ranging from the giant water-serpent Hydra to tiny Crux (the Southern Cross).

These are largely based on the mythology of the ancient Greeks. But they share remarkable similarities with the constellations of the oldest living cultures on the planet.

Hunters and sisters

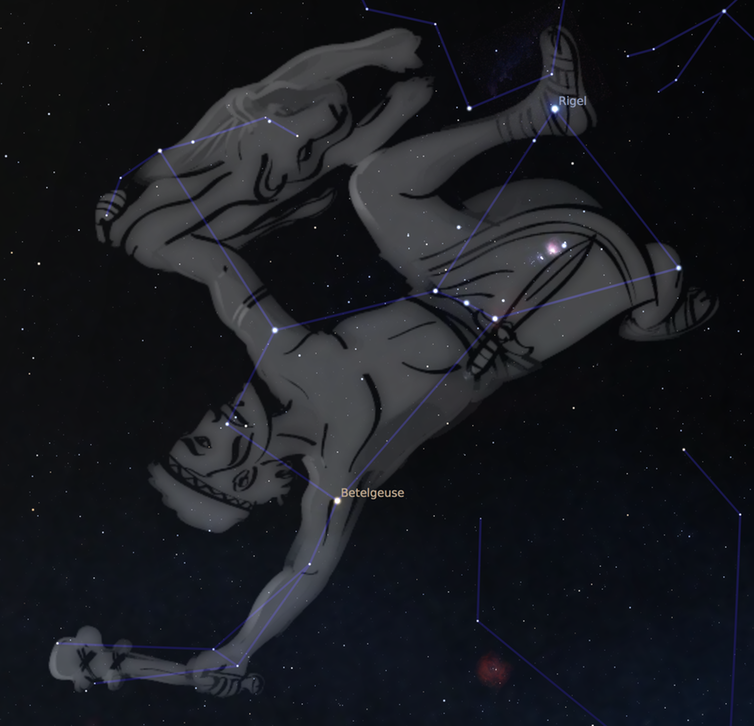

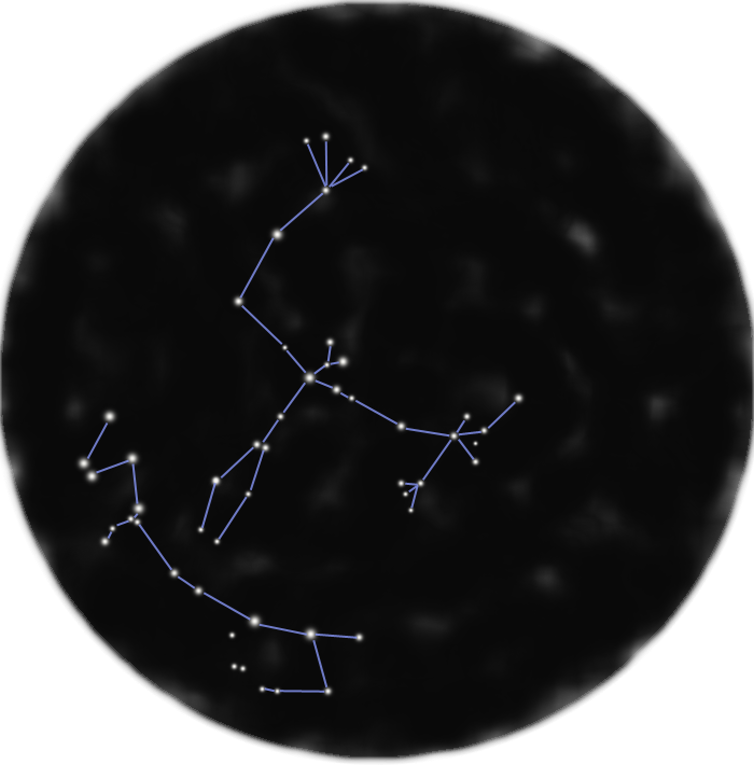

One of the most easily recognisable constellations is Orion. In Greek mythology, the boastful hunter was killed by a giant scorpion.

Orion is constantly pursuing the seven sisters of the Pleiades. In the sky, Orion is defending himself from the charging bull Taurus, represented by the V-shaped Hyades star cluster. The Hyades are daughters of Atlas and sisters of the Pleiades.

In Wiradjuri Aboriginal traditions of central New South Wales, Baiame is the creation ancestor, seen in the sky as Orion - nearly identical in shape to his Greek counterpart. Baiame trips and falls over the horizon as the constellation sets, which is why he appears upside down.

The Pleiades are called Mulayndynang in Wiradjuri, representing seven sisters being pursued by the stars of Orion.

In Aboriginal traditions of the Great Victoria Desert, Orion is also a hunter, Nyeeruna. He is pursuing the Yugarilya sisters of the Pleiades but is prevented from reaching them by their eldest sister, Kambugudha (the Hyades).

Scorpions and canoes

In Greek mythology, the scorpion that killed Orion sits opposite the hunter in the night sky as the constellation Scorpius. They were placed on opposite sides of the sky by the gods to keep them away from one other.

A comparable relationship can be found in the traditions of the Torres Strait Islanders. The culture hero, Tagai, killed his 12-man fishing crew (Zugubals) in a rage for breaking traditional law, before they all ascended into the sky.

Tagai is standing on his canoe, formed by the stars of Scorpius. The Zugubals are represented by two groups of six stars: the belt/scabbard stars of Orion (Seg) and the Pleiades (Usiam). Tagai placed the Zugubals on the opposite side of the sky to keep them far away from him.

The twins

Another famous constellation is Gemini, the twins, denoted by the bright stars Castor and Pollux.

Many Aboriginal groups also view these stars as brothers. In the Wergaiatraditions of western Victoria, they are the brothers Yuree and Wanjel, hunters who pursue and kill the kangaroo Purra.

In eastern Tasmania, the constellation Gemini represents two ancestor men who created fire, walking on the road of the Milky Way – similar in orientation to the Greek constellation.

Bird flying high

Bordering the zodiac near Sagittarius lies the constellation Aquila, the eagle. In Greek mythology, Aquila carried the thunderbolts of Zeus.

In Wiradjuri traditions, Aquila is Maliyan, the Wedge-tailed Eagle. In some Greek and Wiradjuri traditions, the star Altair is the eagle’s eye - despite being seen in different orientations.

Even Indigenous constellations around the world have noteworthy similarities.

The Emu in the Sky, seen by Aboriginal groups across Australia, is composed of the dark spaces in the Milky Way.

The rising of the celestial emu at dusk informs observers about the bird’s breeding behaviour. Across the Pacific, the Indigenous Tupi people of Brazil see the same shape as a rhea, a large, flightless bird that is native to South America and related to the emu.

The rhea’s behaviour is nearly identical to that of the emu and the Tupi and Aboriginal traditions are remarkably similar.

Why the similar stories?

We’ve learned a bit about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander views of the stars.

What we don’t yet know is why different cultures have such similar views about constellations. Does it relate to particular ways we humans perceive the world around us? Is it due to our similar origins? Or is it something else?

The quest for answers continues.

Quelle: THE CONVERSATION