.

29.06.2016

Wir berichtete:

/_blog/2016/06/04/6336-astronomie---helle-feuerkugel-mit-lauten-schlag-ueber-phoenixusa-wahrscheinlich-ein-meteor/

-

After 132 hours of searching, ASU team — in partnership with White Mountain Apaches — locates meteorites on tribal land

On June 2, a chunk of rock the size of a Volkswagen Beetle hurtled into the atmosphere over the desert Southwest at 40,000 miles per hour and broke apart over the White Mountains of eastern Arizona.

A week later, one of Arizona State University’s top meteorite experts was off on a team expedition in the Arizona wilderness on an Apache homeland, braving bug bites, bears and mountainous terrain.

After three nights and 132 hours of searching, they were successful.

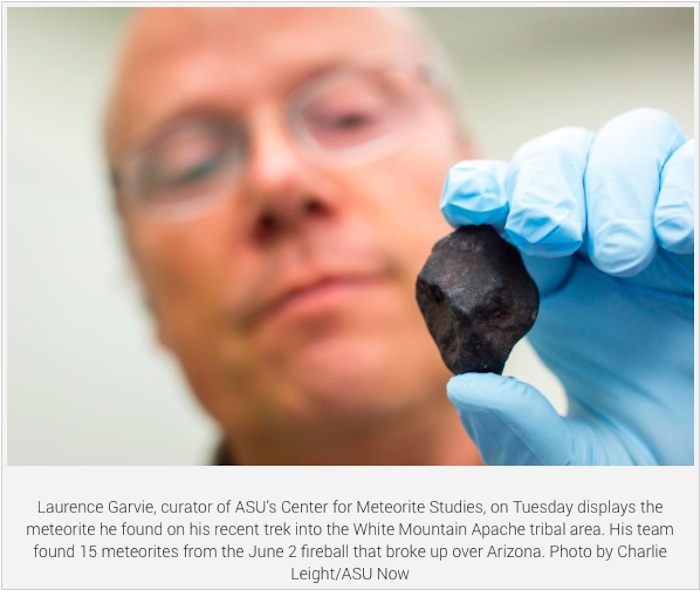

“This is a really big deal,” said Laurence Garvie, research professor and curator of the Center for Meteorite Studies in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at ASU. “It was a once-in-a-generation experience.”

It began when Garvie woke up on June 2, checked social media and saw that dozens of people and cameras witnessed a dramatic meteor fall in the wee hours of the morning. He immediately knew it was going to be a long day.

National Weather Service Doppler radar in Flagstaff swept the area and turned up three strong radar returns on White Mountain Apache tribal land.

“This thing exploded in the atmosphere,” Garvie said. “When the stone breaks up, things just start dropping. ... By simple physics we can estimate where these things are on the ground.”

A lot of meteorite hunters immediately knew where it had fallen, but tribal lands are closed to the public, unless hiking or fishing with a permit. “People were excited, but it wasn’t on public land,” Garvie said.

.

A day or so after the fall, after Garvie had stopped being bombarded for interview requests from the press, he and Jacob Moore, assistant vice president of tribal relations at ASU, contacted the tribal council of the White Mountain Apache Tribe.

“(Moore) was absolutely pivotal to this,” Garvie said.

With tribal permission granted, the Arizona State University–White Mountain Apache Tribe Meteorite Expedition, as Garvie dubbed it, took off for the mountains. Tribal chief ranger Chadwick Amos and Game and Fish director Josh Parker met the team nearby to help them with their search.

Garvie, two grad students from the Center for Meteorite Studies and three professional meteorite hunters invited by the center took off in three high-clearance four-wheel-drive trucks. They brought food and water for a week in case they got stuck.

Like most backcountry roads in Arizona, it was a hairy two-track.

“We drove 5 miles an hour,” Garvie said. They blew a tire (their last spare) at one point. “We drove a mile an hour after that,” he added. “We took 1.5 hours to travel the 7-mile dirt road to our first campsite.”

Everyone was bitten by either cactus or insects. Bears wandered through camp one night. On the way out, they rescued two lost hikers. Because the mountains are tinder dry, they couldn’t have campfires, so they ate canned chili, nuts and jerky. One guy put Reddi-Wip on everything. “It was a real adventure,” Garvie said.

The terrain is beautiful, but rugged. You might want to hike to a point 1,000 yards away, but it involves traversing twice that to get there.

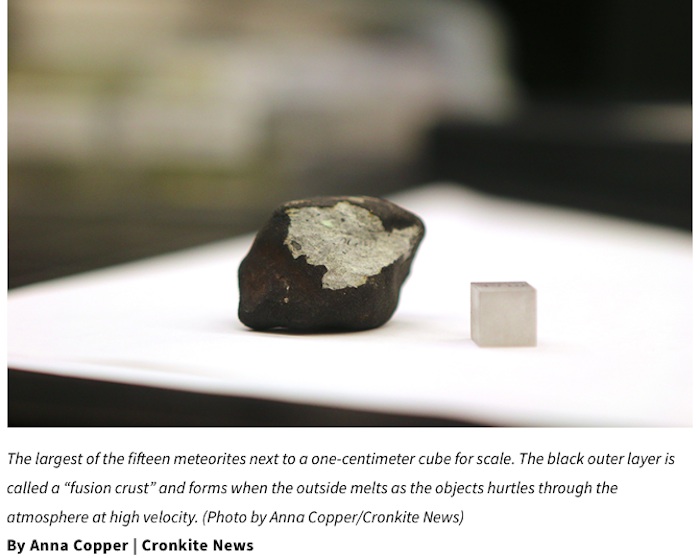

After three nights camping and 132 hours of searching, the team found 15 meteorites, ranging in size from a medium-sized strawberry to a pea. “These are pristine things that were in space a few days ago,” Garvie said.

.

Searching consisted of walking slowly and scanning small patches of bare ground where it would be possible to see a small, black, rounded rock, according to Garvie.

Graduate students from the Center for Meteorite Studies, Prajkta Mane and Daniel Dunlap, both found meteorites.

Dunlap found one the size of a pea in a clump of grass. “Oh man, I can’t believe this is happening,” Dunlap said he thought when he saw it. “Oh my God, is that one? It is!”

“It was an amazing feeling,” he said later.

Mane also found her first meteorite.

“It was crazy,” she said. “You study these things in the lab, but to go into the field with experienced people and find one was really amazing.”

It was the third recovered meteorite fall this year in the United States. The other two were in Mount Blanco, Texas, and Osceola, Florida. All three finds were enhanced by Doppler radar. Without the Doppler data, the White Mountain finds would likely not have been recovered, Garvie said.

The three citizen scientists — Robert Ward, Ruben Garcia and Mike Miller, all well-known to the center — discovered meteorites and handed them off to the collection. It was a condition of their joining the expedition, and they gladly accepted, attracted by the thrill of the hunt.

“I really want to stress how important they were,” Garvie said.

.

It was the second time Garvie has personally found a meteorite. He didn’t expect to find anything on the expedition. “I was hoping,” he said.

Finding a meteorite can be hard, but not impossible, Garvie said. “If you just went out to the western deserts of Arizona and looked really hard, you might find one every few days,” he said.

The meteorites the team found are ordinary chondrites. Chondrites are stony — non-metallic — meteorites that have not been modified from melting or differentiation of the parent body. It was only the fourth recorded fall in Arizona history.

“Every new meteorite adds a piece to the puzzle of where we came from,” Garvie said. “We need to stress how grateful we are to the White Mountain Apache Tribal Chairman Ronnie Lupe for giving us access. This area is normally totally off limits to non-tribal members.”

The meteorites will remain the property of the tribe; the ASU center will curate them. Moore said the university was honored to work cooperatively with the tribe on such a rare scientific discovery.

“They have extended tremendous cooperation in the work the ASU scientists are doing on the White Mountain Apache tribal lands,” said Moore.

Meenakshi Wadhwa, director of the Center for Meteorite Studies and a professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration, said she was proud that the cooperation between everyone involved yielded such an amazing find.

“A fresh meteorite fall is always a fantastic opportunity to learn something new about the origin of our solar system and planets,” Wadhwa said. “I am really proud of the great teamwork between our ASU personnel, the meteorite collectors and members of the White Mountain Apache Tribe that made it possible to collect pieces of this meteorite for the benefit of science.”

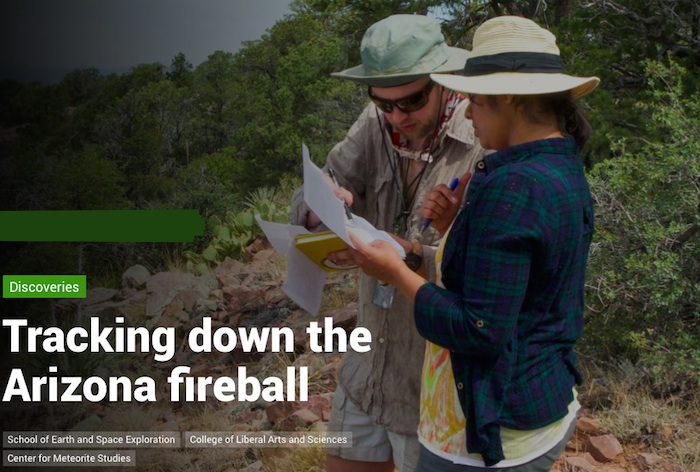

Top photo: ASU graduate students Daniel Dunlap and Prajkta Mane consult their notes while looking for meteorites in the White Mountain Apache tribal lands. Photo courtesy of Laurence Garvie

Quelle: Arizona State University

-

Update: 1.07.2016

.

Space rocks: ASU team finds meteorites in remote Arizona desert

TEMPE — “The vault” is a climate-controlled room that sits behind three locked doors in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University. Housed inside are fifteen charcoal-colored pebbles that collectively weigh less than a quarter of a pound.

Make no mistake: these are no ordinary rocks.

They are the remnants of a roughly 4.5 billion-year-old meteor that streaked across the Phoenix sky earlier this month.

Laurence Garvie, research professor and curator at the Center for Meteorite Studies, knew something big had happened when videos of the meteor sighting appeared on social media early on June 2.

“The question that was in our minds was ‘Is there something on the ground?’” he said.

Although finding any meteorite is rare, finding one so soon after a fall presents scientists with an even more unique opportunity.

“Most of the meteorites we have in the collection—they sit in the desert for hundreds of thousands of years,” Prajkta Mane, a doctoral candidate at the center, said. “This (finding) is very pristine.”

-

Doppler radar indicated a possible strewn field on the White Mountain Apache Reservation in the eastern part of Arizona. The sooner scientists could begin searching the area, the better.

However, because the remnants fell on tribal land, the meteorites technically belong to the White Mountain Apache tribe.

ASU negotiated with the tribe, and just three weeks after the initial sighting, they reached an agreement to allow Garvie and his team to come out and search the area.

“This is a really special union here,” said Daniel Dunlap, also a doctoral candidate at the center. “The tribe had no reason to let us come there, and this is very sacred land to them. They don’t go on it. They don’t let other people go on it. It’s theirs by law to protect as they see fit, and they were nice enough to let us come out and look for (the meteorites).”

“As scientists, if you aren’t fortunate enough to make these occasional ‘wow’ discoveries, it can get very boring and humdrum. You’re just sitting in the lab making another analysis, writing another paper.”

– Research professor Laurence Garvie

Garvie gathered his team, which included Dunlap and Mane as well as three professional meteorite hunters, and together they made the four-hour trip to the reservation and continued another two hours on a dirt road to reach the search area.

They spent four days and three nights in a remote mountainous landscape, canvassing an area roughly eight miles in length by half a mile wide and avoiding bumping into prickly cholla. Garvie said they spent most of that time staring at the ground looking for any traces of little black rocks that “just look different from everything else.”

“You just have to keep walking and walking and walking and just by chance you come around that little bush on the ground and there it’s sitting on the ground—but most of the time it isn’t,” Garvie added with a smile.

But that first afternoon, they were in luck. Within the first half hour, one of the meteorite hunters found the first pea-sized stone. Garvie said that the find changed the game plan immediately. They knew they were in the right. They just had to track down the rest of stones.

They returned to Tempe with a total of fifteen small meteorites, which are now encased in individual plastic boxes back in the vault.

-

The next step will be to classify the meteorites by analyzing the different types of minerals in them. Then they will be named and logged into a public database.

Since doppler radar data suggested there are more, possibly larger, meteorites yet to be recovered from the fall, Garvie considered this first trip to be merely reconnaissance.

Negotiations between the university and the tribe will continue as they work out further agreements to determine the extent to which Garvie and his team can study the meteorites. Should they get permission to move forward, they hope these findings will help them better understand what our early solar system was like.

Another perk, according to Garvie?

“We get to study it first!”

Quelle: Arizona State University.5169 Views