.

The proposed impacts happened 4.3-4.5 billion years ago when the Moon had magma oceans

-

A smattering of water is buried deep inside the Moon and it arrived during the satellite's very early history, a new study concludes, when asteroids plunged into its churning magma oceans.

How and when water got trapped in volcanic lunar rocks is a huge and open question for planetary scientists.

This international team has compared the chemistry of Apollo mission samples with various types of space rock.

They say that icy, early asteroids were the likely source of most of the water.

After such impacts the Moon's developing crust could have trapped the water in the cooling magma.

Much later, volcanic activity spewed some of that magma back onto the surface and, much later again, a precious few of those volcanic rocks were bagged by Apollo astronauts.

Tightly bound up in the rocks is a trace of water: somewhere between 10 and 300 parts per million (0.001-0.03%).

"It's not pools of water, it's not lakes of water, it's not frozen ice. When we're talking about interior - or magmatic - water, we're talking about water that is locked up in minerals," said Dr Jessica Barnes from the Open University in the UK, first author of the new paper in Nature Communications.

The source of that water is a topic of ongoing debate.

.

Recent studies have detected signs of water in lunar rocks from the Apollo missions

-

Previous research revealed that some of these watery deposits have a similar molecular signature to water-rich "carbonaceous chondrite" meteorites that occasionally reach the Earth from the asteroid belt.

So was water brought to the Moon by chunks of asteroid? Perhaps via the very early Earth, which was similarly bombarded before the brutal collision that created our satellite?

Or, as other researchers have suggested, did lunar water arrive in comets - the Solar System's more distant, icy travellers?

Working with colleagues in the US and France, Dr Barnes modelled various scenarios to explore what could have produced the chemistry of the Moon's water as we know it. To run these tests, they surveyed all the published results about the make-up of lunar rock samples and the various possible contributors - from Earth rock to comets.

"We've taken an approach that's the most quantitative so far, in terms of deciphering which types of objects would have been impacting the Moon," she told BBC News.

For starters, her models suggest that comets probably contributed only a tiny fraction of the sub-surface water.

This is largely because comets appear to have "heavier" water - containing more deuterium, a heavy hydrogen isotope - than either Earth, the Moon or asteroids, Dr Barnes explained.

"Our conclusion is it was mostly water-rich asteroids and very, very little contribution from comets," she said.

In particular, her findings point to asteroids with a recipe much like carbonaceous chondrites. These rocks, which today make up up less than 5% of known Earth impacts, have characteristics that seem to reflect "primitive" asteroids.

.

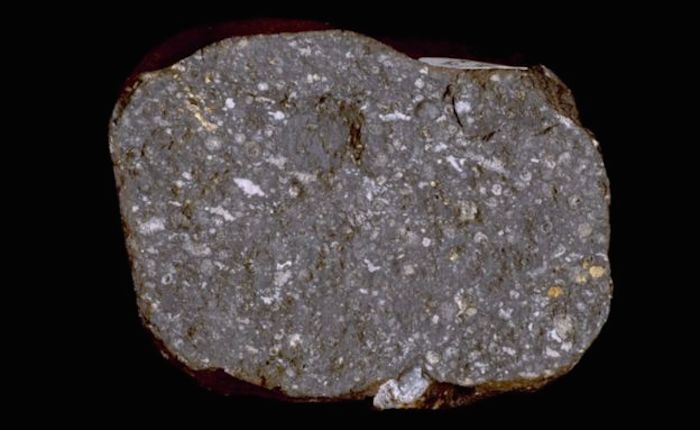

Carbonaceous chondrites are a volatile-rich class of meteorite, derived from asteroids

-

"These are asteroids that didn't go through differentiation to have a core, a mantle and a crust like the Earth and the Moon," said Dr Barnes. "They contain a lot of water and a lot of organic molecules."

Such rocks, she suggests, pummelled the molten Moon some 4.3-4.5 billion years ago, within its first 200 million years.

"We think that the movement of Jupiter and the outer planets, settling into their orbits that they're in today, disrupted the asteroid belt. It would've been very chaotic and you would have had lots of objects flying through the Solar System, impacting the inner planets.

"We're in quite a quiet time at the moment, compared to what happened very early on."

Ancient or modern?

Other researchers see considerable room for doubt in this asteroid-delivery idea.

Dr Jeremy Boyce, a geochemist at the University of California Los Angeles, said while others might doubt the very idea that water was delivered by impacts, his reservation about the new study comes down to timing.

"While I like the idea of adding [water] to lunar basalts through meteorite materials, I'm less comfortable with the idea that it had to happen early in the Moon's history," he told the BBC.

Instead of this ancient bombardment of the molten Moon, Dr Boyce suggests that the water deposits have simply built up on the moon's surface thanks to more recent, continuous peppering by meteorites.

Then, when volcanic eruptions take place, the liquid material could collect those deposits on its way through the crust - resulting in the small amounts of water seen in volcanic rocks.

The concentrations involved are so small, he added, that "it only takes a tiny whiff" of this type of contamination to explain the results.

But Dr Boyce is soon to collaborate with Dr Barnes on fresh research, and he said the vigorous debate currently underway in lunar geology is exciting.

"We all know each other, we all publish papers, we all have polite disagreements about some of the things that we think about the moon. But it's actually a really healthy environment where we're all working towards the same goal from different perspectives.

"It's good to have differences of opinion."

Quelle: BBC

4415 Views