.

Two months shy of twenty-seven years since it was first flown, the F-117 Nighthawk was retired in ceremonies on 21 April 2008 at Holloman AFB, New Mexico, where it had been operated by the 49th Fighter Wing since 1992, and then on 22 April in Palmdale, California, for the people who had designed and built it at the then-Lockheed facilities there.

-

Surprise, Surprise

The US Air Force announced Thursday the existence of an operational stealth fighter aircraft, officially known as the F-117A. The single-seat, dual engine aircraft is built by Lockheed Corporation in California. The F-117A first flew in June 1981. The F-117A has been operational since October 1983, and is assigned to the 4450th Tactical Group at Nellis AFB, Nevada. The aircraft is based at the Tonopah Test Range Airfield in Nevada. A total of fifty-nine aircraft are being procured. Fifty-two have already been delivered to the Air Force and seven more are in production. With disclosure of the F-117A program, this mature system, which has enjoyed bipartisan Congressional support since its inception, can now be fully integrated into operational plans in support of worldwide defense commitments. This system adds to the deterrent strength of US military forces. – US Air Force News Release, 10 November 1988

The Black Jet

The F-117 Nighthawk, the world’s first combat aircraft to fully exploit radar-evading stealth technology, was developed, tested, and flown operationally in complete secrecy. Even the official program name – Senior Trend – was a secret.

First flown in 1981 and operational in 1983, the futuristic-looking stealth fighters were based at the Tonopah Test Range in Nevada, an isolated facility roughly 250 miles north of Las Vegas.

The pilots, maintainers, and support staff of the cryptically designated 4450th Tactical Group would leave their homes at Nellis AFB in Las Vegas on Monday, fly via minimally marked 727 airliners to Tonopah, shift their body clocks to night operations for a couple of days, and then fly back to Nellis on Friday. After the F-117 program was publically acknowledged, the unit was redesignated the 37th Tactical Fighter Wing.

The futuristic-looking F-117, with its overall black paint scheme and faceted surfaces, would enter the national consciousness a little more than two years after the official announcement at the Pentagon. As Operation Desert Storm kicked off, TV news reports showed grainy video of targets in Baghdad, one of the most heavily defended cities on earth, being destroyed with a single 2,000-pound bomb being dropped precisely down an air ventilation shaft.

Two months shy of twenty-seven years since it was first flown, the F-117 was retired in ceremonies on 21 April 2008 at Holloman AFB, New Mexico, where it had been operated by the 49th Fighter Wing since 1992, and then on 22 April in Palmdale, California, for the people who had designed and built it at the then-Lockheed facilities there.

What follows is certainly not a complete history of what was called the Black Jet, but memories from a just some of the hundreds of people associated with the F-117 during its career.

.

During the first nine years of operations, the F-117 was based at Tonopah Test Range in Nevada. The fleet was relocated to Holloman AFB, New Mexico, in 1992. This aircraft (Air Force serial number 85-0816) was assigned to the 8th Fighter Squadron at Holloman. Known as the Black Sheep, the squadron's lineage dated back to World War II.

Have Blue was designed to provide a maneuverable fighter demonstrator with low observable characteristics. Two aircraft were built by the Lockheed Skunk Works using company research and development funding. Only twenty months after contract award, company test pilot Bill Park made the first flight of this aircraft on 1 December 1977. Eighty-eight flights were made on the two Hve Blue aircraft through 1979. Have Blue led directly to the F-117 Nighthawk stealth attack aircraft.

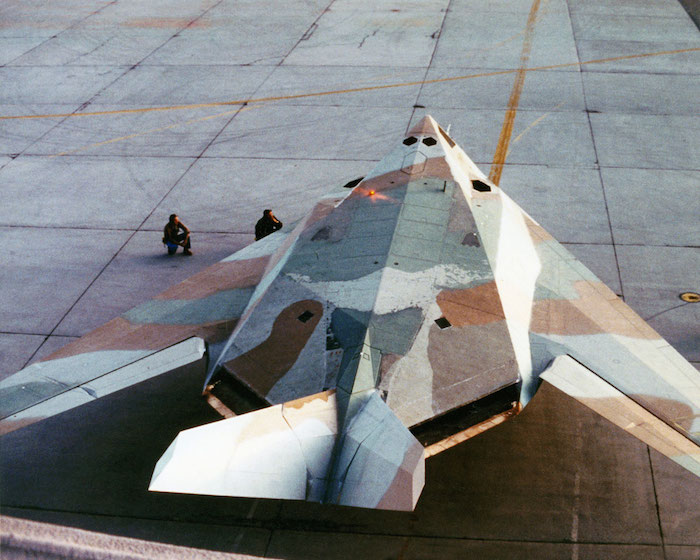

The F-117 Nighthawk stealth attack aircraft was developed in near-complete secrecy. This is the first F-117 (US Air Force serial number 79-10780) during final assembly at the Lockheed Skunk Works facility in Burbank, California, circa 1980. This aircraft was one of five pre-production aircraft that were flown to test performance, stability and control, and mission systems. The test aircraft were all airlifted to test site via C-5, departing Burbank in the middle of the night. Company test pilot Hal Farley made the F-117’s first flight in this aircraft on 18 June 1981, but the existence of the F-117 program was not publically revealed until 10 November 1988. This aircraft is now on display at Nellis AFB, Nevada.

"I was so prepared for the first flight. I had flown the simulator, developed the flight control laws, and had been practicing by flying F-111s and F-16s. We made several taxi runs and had gotten to the point lifting the nose wheel off the ground and deploying the drag chute. I taxied out really early to take advantage of the smoother air at dawn. We didn’t fly with all the computers on during that first flight. Overall, it was a simple flight with the gear down all the way. We did some mild maneuvers in pitch, roll, and yaw." – Hal Farley, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 117

"There was a big party after the first flight, but I stayed behind. I wanted to write the flight test report while everything was still fresh in my mind. I wanted to be as detailed as possible. In the end, I didn’t even get to the party." – Hal Farley, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 117

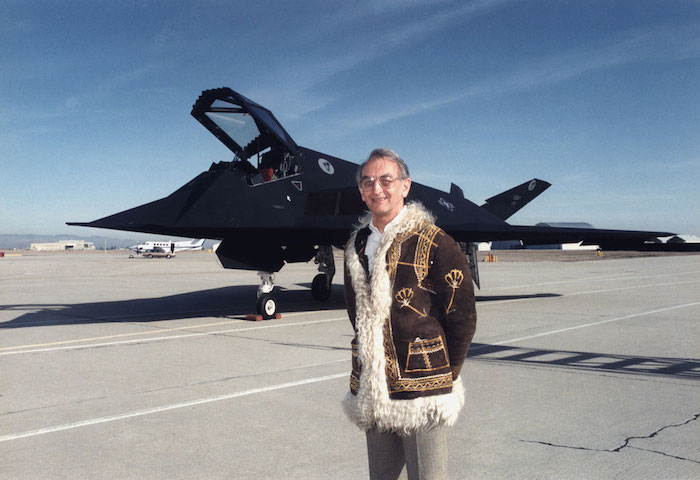

Here, Farley (left) shakes hands with Ben Rich, who led the F-117 development team at the then-Lockheed Skunk Works, after the first flight in 1981.

"I knew information about the F-117 had been released when I saw a photo of my airplane in a Brazilian newspaper with a caption in Portuguese." – Dr. Alan Brown, Lockheed F-117 Chief Technical Engineer

"The jet is easy to fly, but in other jets there is equipment that lets you know what is going on around you, like radar or radar warning. The situational awareness for the pilot just wasn’t there in the F-117. You went into the target alone and unafraid. The other aircraft in the strike package would always want to know where we were. We just didn’t talk on the radio during missions." – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447

"I was the squadron commander of the 410th Flight Test Squadron – the F-117 flight test unit – from July 1997 to July 1999. We had Air Force test pilots and Air Force maintenance, but we also had Lockheed test pilots and Lockheed maintainers to help us. It was the most ideal test force I’ve ever been in." – Crash Jespers, Bandit 121

This image shows test pilot Jeffrey Knowles in one of the dedicated test F-117s over the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 2001.

"We had seven aircraft when I started as a buck sergeant. Anybody who worked on the jet at Tonopah will remember their first launch. We ran completely blacked out operations. It was lights out, comm out. The first time those doors opened with nothing on and nothing out there on the outside. The old timers would tell you that it was ok to freeze. For a long time, we weren’t really sure it was flying. All we’d see was the lights go by." – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

This image illustrates F-117 operations at Tonopah, Nevada, circa 1990.

"The F-117 was based on 1970s technology and the American people got their money’s worth. The military, the contractors, and the civilians kept the program a secret for so long. The F-117 was a national treasure. Everybody knew someday we would use that fighter in a war and it would do a great job. And it did." – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

"Over its career, the F-117 has been deployed to the desert, to Europe, and to the Pacific. The jet has done its job every time. The bombs go right where they are supposed to and you go home." – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447

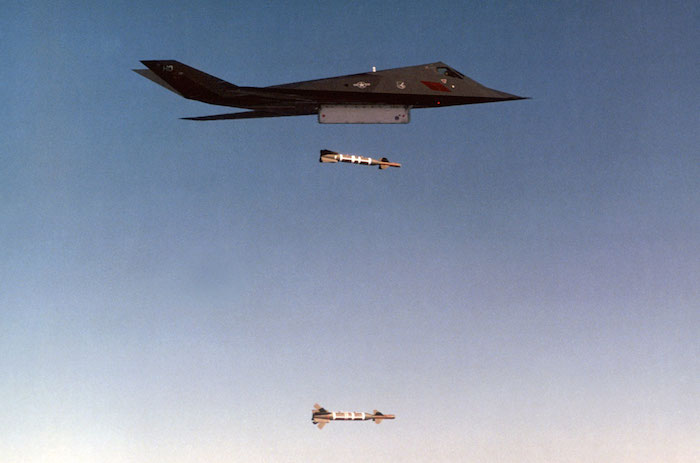

"The GBU-27s we used in Desert Storm were dropped singly. With the GBU-10 and Mk. 84, you could drop simultaneously. They would follow each other in, and you could see both explosions." – Claus Klause, Bandit 283

An F-117 Nighthawk pilot from the 8th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron lands at a forward deployed airfield after completing a mission in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom on 20 March 2003. DoD U.S. Air Force.

A 7th Fighter Squadron pilot flies his F-117 over the hangars at Holloman AFB, New Mexico in 1995. Known as the Screamin' Demons, the 7th FS lineage dated back to World War II.

"Last year [2007], when things in Korea got hectic, the US Forces Korea commander said, ‘Get those black things’ up to the front. We made the F-117’s last deployment and took eighteen jets to South Korea. We knew we were influential. Everybody knows what the jet can do." – Lt. Col. Ken Tatum, Bandit 527

Ten Nighthawks can be seen at Site 7, the Lockheed Martin F-117 Depot at Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, on 21 June 2001. The aircraft were there in preparation for the 20th Anniversary Celebration/Flyover at nearby Edwards AFB a few days later.

Two months shy of twenty-seven years since it was first flown, the F-117 was retired in ceremonies on 22 April 2008 in Palmdale, California, for the people who had designed and built it at the then-Lockheed facilities there. Here, the last four jets are lined up on the ramp prior to the final takeoff.

"I think there is going to be a fight between the four of us as to who will be the very last F-117 pilot to land when we take the jets to Tonopah for storage. I’m thinking I’ll flame out an engine if I have to. Making that last landing will be quite a distinction. – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447, prior to the last F-117 flight on 22 April 2008

Here, the final four F-117s form up after takeoff on the last flight.

"The F-117 was the leadoff batter for stealth combat aircraft. It proved the value of low observable technology and precision weapons delivery that was unmatched." – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

Here, the an F-117 Nighthawk and an F-22 Raptor are flown in formation in October 2006 at sunset over Southern California.

-

In The Beginning

The genesis for stealth came in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The Russians had developed a sophisticated radar network and the Israelis were sending aircraft to the front lines and, even with electronic countermeasures, the Egyptians were shooting them down. What was needed was a way to make the aircraft invisible, or nearly so. If you can’t see it, you can’t shoot at it.

DARPA [the US Defence Advanced Projects Agency] gave $100,000 contracts to two companies [McDonnell Douglas and Northrop] to study the problem. The plan was one of them would build a stealth prototype. Lockheed got a $1 contract that gave us access to the DARPA data. We got in through the back door.

We had produced a stealth aircraft in the SR-71 and DARPA didn’t know about it. We got the CIA to let us brief DARPA on the A-12/SR-71. After some convincing, DARPA officials told us to go ahead and bid on the program.

Dick Scherrer was Lockheed’s director of operations research. He was a very inventive guy. He had helped design some of the rides at Disneyland. He couldn’t get anyone to explain RCS [radar cross section] to him in normal English. I was at home with a broken leg and Dick called me on an open phone line and told me I had to design an invisible aircraft.

The day I came back to work, I explained stealth to him. The lowest RCS is taking the smallest number of flat panels and tilt those surfaces over, sweeping the edges away from the radar view angle. Dick went away and came back with some drawings. I told him to make it flatter, so the radar couldn’t reflect back. He came back with some new drawings.

We got Ben Rich [the head of Lockheed’s Skunk Works] to get some money for an anechoic chamber and to build a wind tunnel test model. The aerodynamics guys gave the design a name – the Hopeless Diamond. It didn’t have a tail. The idea was just to look at the basic shape. But the engineers looked at the model, and said, ‘You know, that would almost fly.”

Scherrer told me to write a computer program to show what we would need to measure RCS. He also said, ‘I need it in a month.’ I was working in the computer group and we would work any kind of problem. I hired my old boss, Dick Schroeder, as a consultant, and it took us five, 100-hour weeks, but we built the program [called Echo 1] to test the Hopeless Diamond design. It worked – our predictions matched reality. I went from being regarded as the village idiot to the village expert.

Shortly after Echo 1 was developed, I became aware of a 1966 Russian technical paper that had been translated in 1971. This Russian scientist had developed a method of manually calculating edge refraction. We adopted some of the principles of that paper to work with Echo 1. I found out later that the Russians referred to me as “Mr. Stealth.”

The Hopeless Diamond design led to the XST design, which was much more of an airplane. The XST design led to Have Blue, which was essentially a subscale version of the F-117. We had a pole model shootoff at the test range at Holloman and did really well.

We turned in our proposal for Have Blue and Ben says to mark this as confidential. There was no classification on us at that point. Two weeks later, we hear from DARPA and the proposal is now Top Secret Special Access Required. We only had two engineers who had DoD Top Secret clearances. We all had Agency clearances.

We got that cleared up and went to work. We had great success with Have Blue. We proved the design would fly. Even though it was completely tested, the Air Force thought there was enough proof to start. They said take the Have Blue design and weaponize it. – Denys Overholser, Lockheed mathematician and engineer

It Is A Model

We built a big wooden mockup of the F-117. We used it to plan where the displays would go and how the wiring and plumbing runs would be installed. The F-117 is probably one of the last aircraft to be mocked up in wood. – Hal Farley, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 117

Flight Control Laws

We spent two years and thousands of hours in the simulator. It was an iterative process. We would get data from the wind tunnel models and put the data in the simulator. We would fly the simulator and evaluate the flying qualities. We took the F-117 control law package to Calspan to fly it in their NT-33 variable stability test aircraft. We told them ‘Go fly this in your aircraft.’ They said ‘What it is it?’ and we said, ‘Just go fly it.’ We also degraded the control laws to see where the corners of the flight envelope were and how well we could handle it. – Hal Farley, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 117

Tumbling Down

Dick Cantrell, one of our aerodynamics engineers, wanted to see what would happen if the F 117 exceeded the AoA limits. He developed a catapult model and he tested it in Building 310 in Burbank [California, then the Lockheed assembly facility] where we had built the Constellation and the SR-71. He launched the model in the hangar and caught it in a net. He could see the aircraft’s departure [from controlled flight] characteristics. When it exceeded the AoA limits, the aircraft would tumble. All of the pilots were standing there watching this test. – Hal Farley, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 117

Dead Of Night

The aircraft was taken from Burbank to the test range in a C-5 in the dead of night. It was loaded in nearly complete blackout conditions. I don’t think the fact a C-5 was landing at the Burbank Airport in the middle of the night tipped the neighbors off to anything unusual. It probably just ticked them off when it took off. – Hal Farley, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 117

First Flight

I was so prepared for the first flight. I had flown the simulator, developed the flight control laws, and had been practicing by flying F-111s and F-16s. The stability system on the F-117 came from the F-111. We made several taxi runs and had gotten to the point lifting the nose wheel off the ground and deploying the drag chute.

I taxied out really early to take advantage of the smoother air at dawn. As I rolled down the runway, I noticed the nose was wandering a little and directional stability wasn’t as great as was anticipated. We didn’t fly with all the computers on during that first flight.

The aircraft doesn’t care if it is flying sideways or straight. The computers control everything. Once airborne, it was yawing more than I liked, and I would flip the switch on the pitch roll gain and the aircraft stiffened up. I heard this bang and I wasn’t ready for that. It was the intake blow-in doors slamming shut. A canopy warning light came on and that was troubling, because the canopy is also the windscreen. Overall, it was a simple flight with the gear down all the way. We did some mild maneuvers in pitch, roll, and yaw.

There was a big party after the first flight, but I stayed behind. I wanted to write the flight test report while everything was still fresh in my mind. I wanted to be as detailed as possible. In the end, I didn’t even get to the party. – Hal Farley, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 117

Small Group

One of the reasons the F-117 came about so quickly was the team that was there. Air Force program management consisted of seven people. We were able to work on-on-one with the experts in the Air Force. We went from paper to airborne in two-and-a-half years. The Air Force team worked with us, gave us good suggestions, and let us get on with the program. – Dr. Alan Brown, Lockheed F-117 Chief Technical Engineer

It’s In Your Hands

I started on the F-117 in 1981. There were eleven people in the 4450th Tactical Group when I joined. Early on, I went in a room in the basement at Lockheed in Burbank and I was told, ‘This is the aircraft and this is how it is supposed to work. Your job is to make sure it does.’ – CMSgt. Kenneth Cody (ret.)

Really Black Program

Thousands of people kept the secret of the F-117 program. I had to take a polygraph test at the beginning, mid course, and at the end. We never even said ‘F-117’ for years. We called it ‘The Asset.’ Since it wasn’t designated the F-19, which is what it probably should have been in sequence, I was able to truthfully answer ‘No, I don’t fly the F-19’ when somebody asked me what I did. – Mark Dougherty, Bandit 168

Team Nighthawk

The thing I most remember is the sense of dedication we all had. We had a real sense of purpose. They were tremendous people and there was tremendous camaraderie. We probably had 400 people at most on the program, including mechanics on the assembly line. We also had one of the first true combined Air Force-contractor test forces. That teamwork was even part of the F-117 revolution. It’s standard practice today. – Tom Morgenfeld, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 101

Stealth Trifecta

After the F-117, I went on to the YF-22. After the YF-22, I came back to the F-117 and flew right up until the time I got involved with the X-35. I probably have about 1,295 hours in the F-117. – Tom Morgenfeld, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 101

Flight Envelope

We cleared a small portion of the F-117’s flight envelope and the Air Force test pilots expanded it on out. Bill Park was the chief test pilot and he made the decision that Hal [Farley] would make the first F-117 flight. I still feel slighted – sort of. I was in the F-117 program for six years and made the first flight of Ship 4. I mainly flew Ship 2 and did a lot of high AoA [angle of attack] tests, high sink rate landings, and stalls. – Dave Ferguson, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 105

Test Fleet

Flight test mission start and then you work your way incrementally through the flight envelope. The first two aircraft were flown continuously. Aircraft 780 is now on a pole [on static display] at Nellis and 781 is at the Air Force Museum. 781 flew a tremendous amount. 782 was just recently retired. That was the mission systems airplane. 783 was the primary RCS test airplane. 784 was a catch-all and did a lot of avionics testing. We were flying fifteen to twenty times a week. We would typically fly as many as two flights in the morning and two in the afternoon. It was a very busy time and we owned a lot of airspace. We did a lot of flying. We spent a lot of time making sure nobody else was around. That added a level of complexity that most programs don’t have to deal with. – Jon Beesley, Bandit 102

Bandit Origin

Bandit was a standard radio call sign used by the Aggressor pilots at Nellis. We used Bandit because it wouldn’t be unusual or draw any special attention. In the test program, you were allowed to pick your number. The test pilots took Bandit numbers 100 to 125. – Dave Ferguson, Lockheed test pilot, Bandit 105

Bandit Legacy

A pilot was given a Bandit number after his first flight in the F-117, which was solo. His name and the date of the flight were embroidered on an aviator’s scarf and then it was hung with the other Bandit scarves. Every single one of those scarves will be going to the Air Force Museum. There were 557 operational F-117 pilots. The operational pilots started with Bandit 150 [Col. Al Whitley]. There was no Bandit 666. The last Bandit was Brig. Gen. David Goldfein, who was the 49th Fighter Wing commander. He’s Bandit 708. – Lt. Col. Ken Tatum, Bandit 527

Blue Suiter

My introduction to the aircraft came before first flight. Skip Anderson was the Air Force’s flight test director. He showed me the airplane and asked me to come aboard as the operations officer for the Combined Test Force. I was the only test pilot from the Air Force for all five years of development and flight test. The whole time I worked there, the program didn’t officially exist. I can remember calling my wife in 1988 after I was off the program and told her to look at the TV when they made the official announcement. I told her that’s what I was doing for five years. She was pretty excited to finally know. – Jon Beesley, Bandit 102

Fin Departure

In 1985, I had a vertical fin explosively flutter off the back of the airplane. We were doing a weapons compatibility test and the aircraft went into a flutter. The general sensation was riding on the crossties of a railroad track on a motorcycle while going fifty miles an hour. We had a bomb hanging out in the airstream and we were able to get it back in. We came back and land the aircraft successfully. We were then able to go fix the problem and re-clear the envelope. We found out some things we hadn’t known before. – Jon Beesley, Bandit 102

Welcome To The Air Force

I spent four years at Tonopah as a weapons troop. I was a young airman, only nineteen years old. It was really exciting. We were in the barracks, called the Mancamp, which was ten miles from the flightline. We even had maid service. I was new to the Air Force and didn’t know any better – I thought it was like that everywhere in the Air Force. – MSgt. Michael F. Parkison, 49th Aircraft Maintenance Squadron, Holloman AFB, New Mexico

First Launch

We had seven aircraft when I started as a buck sergeant. Anybody who worked on the jet at Tonopah will remember their first launch. We ran completely blacked out operations. It was lights out, comm out. The first time those doors opened with nothing on and nothing out there on the outside. The old timers would tell you that it was ok to freeze. For a long time, we weren’t really sure it was flying. All we’d see was the lights go by. – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

Psych

For the distinguished visitors who actually got out to Tonopah, we would show them an invisible aircraft. We would set up a workstand with an air hose held up with fishing line looking like it was attached to the aircraft, and a set of chocks. – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

Local Fauna I

‘Don’t hit the horses’ was a standing order at Tonopah. There were hundreds of wild horses by the road and if you hit one, you would be in all kinds of trouble. – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

Local Fauna II

When I started, there was no billeting in Tonopah. We would fly up there from Nellis every day. Later on, when we had billeting, I would stay for the first launch and recovery and then would go home prior to the second launch of the night. I would be walking to billeting and the horses would follow you and would nip you if you weren’t careful. – CMSgt. Kenneth Cody (ret.)

Local Fauna III

I was walking back to billeting at Tonopah one night through the snow carrying food. I got cornered by a coyote. I just gave him the food and quickly went the other way. – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

On The Other Hand

We had palm readers to get in the secure area. One time I had a broken right hand and the reader would go ‘fail,’ ‘fail,’ ‘fail’ and then I could use my left hand. Those particular readers were right hand first, then left. – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

No Follow-up Questions, Please

The first eight years I worked on the program, I couldn’t tell anybody what I did. I could say I worked on A-7 avionics, and that was the hard part. I knew nothing about A-7 avionics. – CMSgt. Kenneth Cody (ret.)

First ORI

The group’s first Operational Readiness Inspection was memorable. Time just flew by. We had to refuel, load bombs, put in a new brake chute all in the dark. Forty-five minutes was the standard. The evaluator asked me how long it took. I knew we had done it pretty fast, so I guessed about thirty-eight minutes. He said, ‘No, it was a twenty-minute turn time.’ – CMSgt. Kenneth Cody (ret.)

Light Load

You worked on the jet with one hand tied behind your back. One hand had to hold the flashlight with the red lens. There were no night vision goggles. – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

Can I Touch It Now?

Even the janitors outranked us. I was just a buck sergeant. Everybody was so professional. When I started, I kept asking when I could touch the jet. They would only let me look at the jet for a long time. There was a lot of one-on-one training. – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

Through The Looking Glass

Lt. Col. Jerry Fleming [Bandit 152] came to Homestead [AFB, Florida] where I was flying F-4s and interviewed me personally. He landed in an A-7 with no tail markings and he had no insignia on his flight suit. He looked like a CIA guy. I was wondering if I’m still going to be in the Air Force and he says let’s go get some pizza. I’m trying to make sense of all this. He says, ‘What you think you’re going to do is not what you’re going to do. I need you to make a decision now because I need you quick.’ I got orders in two days to report to Nellis. It was fun being wanted. It was even more fun getting picked to fly the F-117. – Mark Dougherty, Bandit 168

What Else Do You Do?

I was flying F-15s at Langley AFB [Virginia] and my commander came and asked if I wanted to join the 4450th Tactical Group. I knew they flew the A-7 and I heard they did other things as well. We had a pilot in the squadron who had come from the 4450th and he told me it would be a great thing to do. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

SLUF Time

All the pilots first went to Tucson [Davis-Monthan AFB] to learn to fly the A-7. We used the A-7 to chase the F-117 and also to prepare us to flight at night. When we were done, they put us in a secure room at Nellis and showed us video of the F-117 taxiing out and flying. That was my first chance to see the aircraft and see that it can fly. It doesn’t look very aerodynamic. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Initial Cadre

We had a whole bunch of hard-charging guys. Everybody had at least 1,500 flight hours. We had one or two F-15 and F-16 pilots and a lot of F-111 or A-7 pilots. In those early days at Tonopah, we flew the A-7 a lot more than the F-117. It was simply a matter of having more A-7s on the ramp. We did the operational test and evaluation and developed tactics and procedures. We took our business pretty seriously. – Mark Dougherty, Bandit 168

Got To Go

I was working at TAC headquarters at Langley and my boss asked me if I was serious about going any place, any time, any where to get back to flying airplanes instead of a desk job. I said ‘uh-huh.’ He said call this guy. So I called Col. Mike Short, who was the 4450th Tactical Group commander at Nellis. I’m going to bring you on as the ops officer for avionics testing in the A-7, but I can’t tell you anything about what else you’re going to be doing. I accepted the assignment and went to Nellis. I knew I didn’t know what the secret was beyond the A-7. I didn’t know what the program was. – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

Joining Up

I signed my life away and was then taken into a vault. There was a standard projector and they showed the frontal view of the F-117 coming out of the hangar. It was a jaw-dropping experience. The only thing that was more jaw-dropping was when they took me in the hangar at Tonopah, the personnel door was closed behind us, and turned the lights on and I saw the jet for real. – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

Big Sweep

My initial briefing was in the vault in Building 927 at Nellis [AFB, Nevada]. I was show photos of the aircraft and my initial reaction was ‘What the hell is that?” The sweep of the wings – seventy-two degrees – was striking. I wondered how that thing flew. It was sort of disconcerting to look at it. I figured it must have very high speeds for taking off and landing. – Mark Dougherty, Bandit 168

Life In Tonopah

Flying from Nellis to Tonopah, we essentially moved a small city of people back and forth every week. We would get there on Monday, fly a short schedule and then come back and play midnight basketball to try and stay awake. We’d fly a full schedule on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday night. One turn, two goes flying the A-7 or the F-117. The A-7s were parked outside the hangars partly as camouflage for the base, but it was cold and dark getting into them. It was warm and light in the hangars where the F-117s were parked. They eventually had trailers for us to live in with heavy curtains to keep out the sunlight. However, the beep, beep, beep of the trash truck backing up early in the morning could penetrate anything. – Mark Dougherty, Bandit 168

Nighthawk Night Owls

We flew at night under the cover of darkness. We would sleep until late in the day in what we called our cocoons or caves. They were completely dark with blackout curtains. We would get up, exercise, go eat, and go to the office. After dark, we would take the jets up and go fly a mission. We would finish between one 1:00 and 3:00 am. We would debrief, clean up, and relax a little. We would have to be in our caves by sunup. You had to be in the dark to minimize the psychological effects on your body and your circadian rhythms. On Friday, you’d go home and try to get to sleep at 11:00 pm when you were used to staying up until 5:30 am. Then your four-year-old would come in at 7:00 am and jump on your chest. And, of course, the only time the dishwasher would overflow or the car would break down was while you were away. – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

I Can’t See You

When the program was in the black world, we only flew on the Nevada Test Ranges. We slowly expanded and went into other airspace. We would file our file plans as A-7s. We would hear airline pilots say they couldn’t see the other traffic that was being called to them. We were in black jets running with lights out. They couldn’t see us and that was pretty cool. Until we came out of the black, our cover story was that we flew A-7s. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Out In The Open

Halfway through my tour at Tonopah, DoD issued the grainy photo of the stealth fighter. Families were then able to talk to one another. We could then show the American public what we could do. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Jato Preto

I knew information about the F-117 had been released when I saw a photo of my airplane in a Brazilian newspaper with a caption in Portuguese. – Dr. Alan Brown, Lockheed F-117 Chief Technical Engineer

Jumping In The Deep End

I was selected to be a squadron commander before I even flew the F-117. Morale was low in one of the squadrons and time was tight because of an ORI [Operational Readiness Inspection], so the wing commander made the change. I pretty much came in from the cold. I knew the people, but I knew I needed to get vector going in the right direction for the ORI. I went off for a week and learned to fly the jet. It was really a matter of rallying the people who knew what to do to get the job done. – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

Limited View

The jet flies better than you think it would from looking at it. The visibility for the pilot isn’t good, but the jet was designed to minimize radar signature, and the canopy had to be a certain shape. – Lt. Col. Ken Tatum, Bandit 527

Limited SA

The jet is easy to fly, but in other jets there is equipment that lets you know what is going on around you, like radar or radar warning. The situational awareness for the pilot just wasn’t there in the F-117. You went into the target alone and unafraid. The other aircraft in the strike package would always want to know where we were. We just didn’t talk on the radio during missions. – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447

Martian Kudos

I have to give a lot of credit to our Martians – the maintainers who kept up the low observable materials on the jet’s skin. We quite literally placed our lives in those young Airmen’s hands. – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447

Different Personalities

Our maintenance troops knew every little detail about every jet. Each aircraft has a different personality – little quirks in how it flew or worked. The crew chiefs gave the jets individual nicknames. – Lt. Col. Ken Tatum, Bandit 527

Weaponology

The GBU-10 Paveway II 2,000-pound laser guided bomb and the Mk. 84 general purpose bomb were the baseline weapons for initial operational capability. I was working weapons integration and was working a program called Have Void for an improved 2,000-pound penetrating weapon. This weapon needed to penetrate concrete and not fracture.

We took the more compact guide fins from the Paveway II and the penetrating capability of the BLU-109 warhead and clooged them together. We did a very slow fit check to make sure it would fit in the F-117’s weapons bay. I called the program office and they sort of got mad. I wasn’t authorized to do that kind of thing. After getting chewed out, they turned around and asked, ‘Well, how did it do?’ It was so new, it was called GBU-XX.

I drew up the requirements and Tactical Air Command went forward on IOC with it. It worked so well, that TAC threw out the toss delivery mode. The weapons guys said, ‘This is stupid. We are not going to fly straight and level to a target, even though that’s the best way to deliver weapons. In the first test, the GBU-27 split the barrel. It later went directly down an air shaft in Baghdad. – Chuck Pinney, Former Air Force F-117 Program Office Director

Follow The Leader

The GBU-27s we used in Desert Storm were dropped singly. With the GBU-10 and Mk. 84, you could drop simultaneously. They would follow each other in, and you could see both explosions. – Claus Klause, Bandit 283

Solo Flight

The first time you flew the F-117, you flew it alone. It was never a bad aircraft to fly. ‘Wobblin’ Goblin’ was a phrase invented by somebody who liked to rhyme words. The aircraft always flew pretty well. – Jon Beesley, Bandit 102

Not For Beginners

You learn to fly the F-117 in the simulator. Your first flight is solo. You have to have 750-1,000 fighter hours to get in. It flies like any other fighter tactically. But you usually go with seven other aircraft all at the same time. – Col. Jack Forsythe, Bandit 460

Family Affair

My wife and I both got stationed at Nellis with the 4450th Tactical Group at the same time. I had to go to Tucson, Arizona [Davis-Monthan AFB] to learn to fly the A-7, so she actually saw the stealth fighter before I did. Later on, my wife and I both deployed with the unit in support of Operation Desert Shield and Desert Storm. Once combat started, she would be there to meet me when we landed. A few of the other pilots also deployed with their wives who were also in the unit. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Home Front

The time in Tonopah was tough on families. But the people you worked with became your family away from your family. They were the only people you could talk to about what you were doing. But you knew it was a safeguard for the defense of the United States. – CMSgt. Kenneth Cody (ret.)

Tropicana or Golden Nugget?

My wife and I knew what each of us did and where we went on Mondays. People told us we should sell all of our household good and just live in the Vegas casinos on the weekends. We both spend all week at Tonopah. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Lifestyle Change

The lifestyle of going away on Monday and coming home on Friday was probably not the most stressful aspect of what the men and women in the program had to endure. The inability to talk about what you did for five days out of seven with your family, your friends, and neighbors was a big challenge. In between, you were very limited on phone calls and communications. We were 250 miles north of home in a location at a higher elevation where it would actually snow. You could be talking with your family and even having the usual social conversation of ‘How is the weather?’ and you couldn’t say. It was an ‘I can neither confirm nor deny that’ situation. The inability to tell somebody how your week was like was hard. You could ask how your spouse’s week was, but it was like your week didn’t exist. – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

Separate Conversations

We were a tight-knit group. We hung out on weekends together and attended a lot of social functions together. The pilots would get together in one area of the house or yard and the spouses met in another. We couldn’t talk about what we did away from Tonopah. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Unique Distinction

When I arrived at Tonopah, the squadron commander was Lt. Col. Bill Lake. He chose me to fly the mission during Operation Just Cause, which was unique. We didn’t even go into Panama in stealth mode. We were chosen because we could drop a precision munition and hit what we aimed at with a specific time on target. We were told to hit a field. We didn’t really show what stealth could do. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Getting Real

In Desert Shield, we really didn’t believe we were going to war until the second squadron arrived in theater in December of 1990. Then, we started getting serious. We did a lot more target study and reading up on Iraqi order of battle. When we got the warning order, we realized we were going to war. – Claus Klause, Bandit 283

Limited Asset

There was a general worry going into Desert Storm about whether the stealth stuff really worked. The naysayers said we were going to lose one or two aircraft a night. If that was the case, it wouldn’t have been a problem for long – we only had a very small number of aircraft. – Claus Klause, Bandit 283

First Night

Having dropped a bomb in Panama, I was chosen for the first mission of Desert Storm. On the first night, none of the pilots knew whether stealth would work or not. The engineers told us what it could do and we trusted them, but until we got through the enemy air defenses in Iraq, we weren’t sure. We anticipated some losses that first night. But we got back and none of us had been hit by triple-A [antiaircraft artillery] or SAMs [surface-to-air missiles] and we knew stealth worked. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Opening Shot

We only had four guys who had been in combat, but they were all professional pilots. All I said to them was, ‘This is Night One and you are going to hit your targets. Concentrate on getting the job done. Put your [ejection] seat all the way down and don’t even look out the window. We had a couple of devastating strikes and we took the Iraqi C3I off the air. The mission was a great success. – Claus Klause, Bandit 283

See It Live

I was watching CNN’s coverage of the opening night of the Gulf War. I saw the explosions going off in the background, and then the power went out. The air raid sirens started going off after that. I knew it was the F-117s and I knew we had succeeded. – Denys Overholser, Lockheed mathematician and engineer

Shack

During a drop, we would fly in on autopilot and put the cursor on the target. We would get consent to release and the doors would come open. You could feel the bombs leave the bomb bay and it was sometimes such a jolt that it would knock the autopilot off. You couldn’t hear them, obviously, but you could see the splash. You knew immediately if you hit the target. – Claus Klause, Bandit 283

Fourth Time’s The Charm

For deeply buried targets like Sadam’s [Hussein] bunkers or the chemical [storage] bunkers, we’d have four pilots attack the target. The first bomb would move the sand. The second guy would hit the same spot, the third guy would breach the target, and the fourth would destroy it. We went after the C3I bunkers or antennas first, and then we went after bridges and dropped the spans. We dropped on SA-2 SAM sites – the BUFFs [B-52 bombers] wouldn’t go in until the missiles were gone. – Claus Klause, Bandit 283

Improving The Jet

I was the squadron commander of the 410th Flight Test Squadron – the F-117 flight test unit – from July 1997 to July 1999. We had Air Force test pilots and Air Force maintenance, but we also had Lockheed test pilots and Lockheed maintainers to help us. It was the most ideal test force I’ve ever been in. The depot was there; the engineering was there; the experience was there. We put the ring-laser gyroscope in the aircraft, GPS; and the new brake controller. We did the testing and development for the single configuration fleet. Our job was to keep the signature and reduce maintenance. We did that. – Crash Jespers, Bandit 121

Keeping Information Flowing

I came to Holloman [AFB, New Mexico] a lot to brief the 8th and 9th Fighter Squadron pilots. I would interface with the operational pilots and their commander. It kept up rapport with the operational force. We had an operational test detachment at Holloman. Everything was right there for the operational pilots. Our OT guys would research how the operational guys would use a new piece of equipment. We tried to keep a free flow of information back and forth. Those were some fun times. – Crash Jespers, Bandit 121

Changing Priorities

When we started, the priorities were (1) security overall, (2) low observable performance, (3) software, (4) aircraft performance, and (5) cost. By 2001, everything was about dollars. In 2000, there was an effort to eliminate six aircraft from the fleet as a cost-cutting measure. We had to defend why we needed to keep the aircraft operational. – Chuck Pinney, former Air Force Program Office Director

Life At Holloman

On my second tour in F-117s, the wing was in the white world. We had relocated to Holloman and things were moving very well. It was a time when lots of things were happening. We were quite often called on to execute deployments and we did on several occasions. Some of those deployments came under the cover of darkness and we did them well. We packed equipment and flew the aircraft out of town and nobody noticed. Other times we went overseas in support of contingencies. When we deployed for Kosovo, one squadron went to Aviano in Italy and one squadron went to Spangdahlem in Germany. – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

Making A Statement

We wanted to go to Aviano for Operation Deliberate Force in Bosnia. We were going to put about 300 people forward, but Italy wouldn’t let us in and the aircraft never arrived. To them, the F-117 in country was an indication of an escalation in force. That makes a key statement. – Col. Jack Forsythe, Bandit 460

No Go/Go Now

While I was commander of the 9th Fighter Squadron on my second tour in the F-117, we were supposed to deploy in support of Operation Deliberate Force in Bosnia [1995]. Due to some political reasons, squadron personnel deployed, but the host nation didn’t allow the F-117s in country. We were not allowed to participate. We did deploy to Kuwait for Operation Desert Strike [1996] and our presence, we felt, was one of the main reasons Sadam backed off the border and avoided conflict. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Shootdown

As a wing commander, you always want all the aircraft to come back and all the pilots back on the ground healthy and happy. Unfortunately, one time it didn’t work out that way. In Kosovo, one of the F-117s was shot down by a SAM. I was in New Mexico and the squadron was deployed.

We knew the pilot had gotten out and was in his parachute. He had the presence of mind to pull out his emergency radio and relayed that information. We wanted to keep it under wraps. You are not going to hide the fact that an aircraft is shot down or goes down. But we didn’t want to highlight the fact the pilot wasn’t back in friendly hands.

I had to break the news to the pilot’s spouse without being overly optimistic or overly pessimistic. Fortunately, she was a uniformed officer, so I could call her into my office, rather than make a visit to her home and draw all kinds of attention. I told her where we were and that I would keep her up to speed.

Later that night at my vice wing commander’s going away dinner, there came one of those sterling moments one life when you get to go up to the podium, take the microphone and relate the fact that the pilot of Vega 31 [radio call sign] has been picked up, is in US hands in a US helicopter, and is on his way to a safe haven. He got back to Aviano and we got his wife on the phone and all was good. – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

JDAM Addition

We could do close air support when the capability to drop JDAM [the GPS/inertial-guided, 2000-pound GBU-31 Joint Direct Attack Munition] was added to the aircraft. It was easy to retarget the weapon in flight. We would get the coordinates of a new target and drop it there. Ten years ago, we would have never even thought about dynamic retargeting with the F-117. You went where the mission was planned to go. With laser-guided bombs, we’d get to the release point and the weather would be bad and we couldn’t drop. – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447

Keep On Keepin’ On

We were combat capable until the very end. The F-117 retirement has been a leadership challenge. There could have been an attitude of ‘why are you still worried about that?’ There is too much history in this aircraft to not to be worried about it until the end. There is a lot of love for this airplane all up and down the chain of command. It wasn’t very hard to keep people motivated. – Col. Larry Stephenson, 49th Maintenance Group Vice Commander, Holloman AFB, New Mexico

Roadside Attraction

The American public just loved the F-117. The crowds would always flock around us at airshows. There was just something about this aircraft. When we took off out of the depot at Palmdale, people would pull over to the side of the road and watch. I had about 300 hours in the jet and we put up a four-ship formation for my fini flight. We just about shut down the highway. – Crash Jespers, Bandit 121

Been Everywhere

Over its career, the F-117 has been deployed to the desert, to Europe, and to the Pacific. The jet has done its job every time. The bombs go right where they are supposed to and you go home. – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447

What Goes Around

We had to modify some of our load and test equipment for the F-117. Now that the jet is retired, that equipment is going back into the inventory. I’m now the head of the weapons shop and I have young troops who are complaining, ‘Who did this shoddy work?’ I’ve never told them that it was probably … me. My career’s come full circle. – MSgt. Michael F. Parkison

No Letup

We were moving full throttle even at the end. We stopped training a week before the aircraft was officially retired. We could have been called up right up until the last minute. – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447

Influence

Last year, when things in Korea got hectic, the US Forces Korea commander said, ‘Get those black things’ up to the front. We made the F-117’s last deployment and took eighteen jets to South Korea. We knew we were influential. North Korea came back to the Six Party talks because we were there. We did that. Everybody knows what the jet can do. – Lt. Col. Ken Tatum, Bandit 527

Last To Land

I think there is going to be a fight between the four of us as to who will be the very last F-117 pilot to land when we take the jets to Tonopah for storage. I’m thinking I’ll flame out an engine if I have to. Making that last landing will be quite a distinction. – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447, prior to the last F-117 flight on 22 April 2008

Lasting Legacy

Anybody who touched this aircraft will be sad to see it go. We will probably never be able to do what this program did. There was a lot learned on this aircraft that is being applied to every other stealth aircraft. – Crash Jespers, Bandit 121

Game Changer

There was a lot of pride in the F-117. You knew you were making history working on it. This aircraft changed the way we fight wars. You don’t want to see war, but you need to be prepared for it. – SMSgt. Wendy Jones (ret.)

Old School

I was here in 1995 and 1996 and from 2007 to 2008 and the jet always amazes me. The fighter we flew into combat has no radar, no radar warning, no chaff, and no flares. What it can do makes it unique. We relied on signature, which was maintained by our maintainers. – Col. Jack Forsythe, Bandit 460

All Star

The F-117 is the most capable air-to-ground platform in history. This jet changed the way people think about attacking ground targets. We were the first to use stealth. From concept to being fielded, development of this aircraft was amazingly fast. – Lt. Col. Todd Flesch, Bandit 447

What A Team

We had an Air Force and industry partnership that worked very well. We trusted the geniuses who developed the aircraft and they came through for us. The Lockheed engineers and technicians always came up to help us. It was a neat, flexible organization for an aircraft that was developed in secrecy on time, on schedule, and on budget. The program worked. – Mark Dougherty, Bandit 168

National Treasure

The F-117 was based on 1970s technology and the American people got their money’s worth. The military, the contractors, and the civilians kept the program a secret for so long. The F-117 was a national treasure. Everybody knew someday we would use that fighter in a war and it would do a great job. And it did. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

Hearts and Minds

We were at Wright-Patterson for the program office farewell. I went to the Air Force Museum and I realized this aircraft has entered the national mind. It’s like the B-17, P-51, or F-86. The jet’s capability also stuck in an adversary’s mind. Kim Jong Il went into hiding when we deployed to South Korea. When we deployed, it was national news. – Col. Jack Forsythe, Bandit 460

Nighthawk Alumni

This was a unique program. The people involved still see each other and go to reunions. It is a testament that we kept this aircraft a secret until we needed to use it in combat. – Maj. Gen. Greg Feest, Bandit 261

New Paradigm

The F-117 changed combat capability overnight. The thinking changed from how many sorties does it take to destroy a target to how many sorties can be destroyed on a sortie. I’m proud of the ground-breaking legacy of this aircraft. We really did own the night. – George Zielsdorf, Lockheed Martin F-117 Program Manager

Nighthawk Legacy

The F-117 is regarded as one of the great success stories in aviation history. It made an impact on the Air Force and on the future of combat operations. Ben [Rich] trusted the engineers and mathematicians. He knew this aircraft would work. He never doubted that the team could delivery the jet on time and on budget. And they did. The F-117 retires at its peak. – George Zielsdorf, Lockheed Martin F-117 Program Manager

Unmatched

The F-117 was the leadoff batter for stealth combat aircraft. It proved the value of low observable technology and precision weapons delivery that was unmatched. – Bill Lake, Bandit 252

Footprints

The F-117 changed the way wars are fought. This country has not started a major conflict when those little black airplanes were not asked to kick down the door. They are a critical part of history. – Jon Beesley, Bandit 102

Quelle: CO

6930 Views