31.10.2025

As the Artemis program works toward its first lunar landing on the Artemis III mission later this decade, new lunar spacesuits are finally being tested by Axiom Space. Meanwhile, the existing spacesuits aboard the International Space Station (ISS) are showing their age. A new inspector general report detailed risks to the Station’s extra vehicular activity (EVA) capability caused by contractor and suit issues.

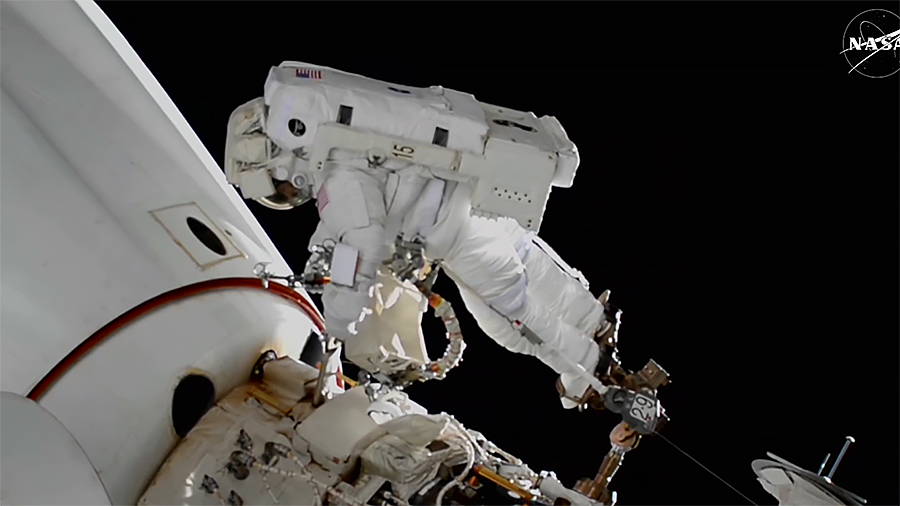

International Space Station EMU

The Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU), the long-serving Shuttle-era spacesuit, is currently used aboard the International Space Station for all EVAs from the United States Operating Segment (USOS) and its Quest airlock. There were four EMUs — numbers 3003, 3009, 3013, and 3015 —as well as spare parts on hand on the Station as of June 2025.

Astronauts use the EMUs whenever they leave the airlock to perform upgrades, major installations, repairs, and other maintenance tasks that need to be performed by an astronaut rather than through robotic means. Astronauts have performed 277 EVAs for Station assembly, maintenance, and upgrades, including USOS and Russian segment EVAs, with a total of 73 days, 1 hour, and 3 minutes of spacewalking time for the ISS as a whole as of Oct. 28, 2025.

There have been 93 EVAs performed using the EMU from the Quest airlock on the USOS without a Shuttle present, to go along with many spacewalks conducted from the Shuttle airlock while docked to ISS, or EVAs from the Quest airlock done as part of a Shuttle mission to ISS. Prior to the ISS first element launch in November 1998, the Shuttle program conducted 41 EVAs using the EMU.

Astronauts Don Peterson and Story Musgrave conduct the first EVA of the Shuttle program. (Credit: NASA)

NASA originally contracted for the EMU starting in the 1970s for the Space Shuttle program, with the suit drawing on technology and lessons from the Apollo A7L lunar spacesuit. Hamilton Standard and ILC Dover teamed up and won the competitive bid to build the spacesuit in 1974, and delivered the first EMU units to NASA in 1982. The STS-6 crew aboard Challenger completed the first Shuttle spacewalk in April 1983. NASA continues to use the same basic design, with enhancements, to this day.

The spacesuit consists of two major subsystems, the Pressure Garment System (PGS) and the Primary Life Support System (PLSS). The PGS comprises the Hard Upper Torso (HUT), arm and leg assemblies, gloves, and boots. The PLSS completes the spacesuit as the life support backpack that supplies the astronaut with breathable air, water, battery power, and other functions critical to their survival during the EVA.

The EMU’s usage will likely end with the Station’s decommissioning in the 2030-2031 timeframe if it is not replaced earlier. The EMU is out of production, and the suits are aging, with issues forcing cancellations and delays of some recent spacewalks. Following a series of mergers over the decades, the original EMU contractors are now part of Collins Aerospace, which is the sole source for support of the current EMU.

The OIG report

On Sept. 30, 2025, NASA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) released a report highly critical of Collins Aerospace’s performance on its contract to maintain the Station’s EMU suits. The OIG report detailed concerns regarding the contractor’s management practices, delivery delays, cost overruns, and quality issues, as well as design flaws in the suits themselves.

The report also questioned NASA’s evaluation of the contractor’s work as well as some of the contract fee awards. The OIG outlined three recommendations to NASA to hold the contractor more accountable and deliver improved performance, while also noting that NASA has limited leverage over the contractor due to its sole-source status and award fees not being a sufficient motivator for improvement.

Collins Aerospace was awarded the $324 million cost-plus-award-fee Extravehicular Activity Space Operations Contract (ESOC) in 2010. Originally lasting five years, NASA needed to extend the contract, and ESOC — currently valued at $1.5 billion — is now running through 2027.

However, the NASA OIG reported risks related to sustaining the EMUs in 2017 and 2021, and NASA outlined concerns regarding Collins Aerospace’s management of ESOC and other contracts with the agency in 2023. NASA’s letter to Collins’ senior management expressed concern about the contractor’s declining performance on the ESOC contract and its impact on the agency’s operations and goals.

The report noted that Collins performed well on operations support during spacewalks, but that NASA’s scores for determining award fees were inflated relative to the contractor’s performance as a whole. This was due to a lack of emphasis on the technical performance and management portion of the criteria, as well as scoring the contractor’s performance over the lifetime of the contract without emphasizing more recent difficulties.

EMU Issues

The EMU, which is well past its designed lifespan of 15 years, experienced a nearly catastrophic water leak during EVA-23 on July 16, 2013. The leak ended up filling up Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano’s helmet with enough water to cover his eyes, ears, and nose.

Though Parmitano and NASA’s Christopher Cassidy ended the EVA early and safely reentered the Quest airlock, the space agency regarded the incident as a “high visibility close call”. NASA traced the issue to blocked drum holes in the suit’s water separator, spilling water from the cooling loop into the ventilation loop.

Although NASA was able to resume planned spacewalks in September 2014 after modifications to the EMU, including a helmet absorption pad, another incident involving water in the helmet occurred in March 2022. Toward the end of EVA-80, German astronaut Matthias Maurer’s helmet visor was coated in a thin film of water covering half of the visor, and the absorption pad was wet.

In this case, excess water escaped from the EMU’s suit cooling system sublimator, which converts liquid directly to gas to keep the spacesuit’s internal environment at an acceptable temperature for the astronaut. Additional absorbent pads were added to the EMU before spacewalks could resume.

In June 2024, NASA astronaut Tracy Caldwell Dyson’s spacesuit experienced a water leak in a service and cooling umbilical unit. The leak forced her and Michael Barratt to abort EVA-90 before they could perform any tasks. Spacewalks from the USOS resumed in January 2025 after replacement of the faulty unit.

These issues, along with others reported by astronauts during spacewalks, were mentioned in the OIG report as examples of problems with the EMU affecting NASA’s ability to continue spacewalks from the USOS.

Besides mechanical issues, astronauts reported shoulder and hand injuries caused by factors such as high internal pressure and limited glove mobility, inadequate suit fit, issues donning and doffing the HUT, and body position.

Contract performance

EMU parts are supposed to be replaced or inspected at routine intervals; PGS components are replaced every eight to 10 years, while PLSS components are replaced as needed. Spacesuits are returned to Earth aboard Cargo Dragon spacecraft and refurbished before returning to the Station.

Astronauts must perform some maintenance tasks on the suits as part of their duties on the Station, and some of these tasks were originally intended to be performed by technicians on Earth with specialized tools and in clean rooms.

However, critical parts needed to keep the EMUs in operational condition are being delayed. The OIG report cited delays in producing critical spares; for example, a fan pump separator — the same part implicated in the EVA-23 water leak — was supposed to be delivered in 2022 but was pushed back to late 2025.

A carbon dioxide sensor to be delivered in 2020 was so late that NASA issued a stop-work order; the agency will rely on existing carbon dioxide sensors — which have failed on a few EVAs — for the remainder of the Station’s life.

Astronaut Tracy C. Dyson seen in her spacesuit prior to the truncated EVA-90 spacewalk in June 2024. (Credit: NASA)

A new sublimator and a refurbished shear plate assembly are also overdue. NASA officials mentioned the sublimator — the part implicated in the EVA-80 water leak — as one of the highest risks for maintaining EVA capability, and the sublimators currently in use for the ISS suits on the Station are past their design life.

Certain spacesuit parts manufactured by Collins were found not to meet quality standards as well. One example cited in the OIG report was a HUT shipped for use on ISS with a shoulder bearing that did not meet minimum requirements for pressurized time. Other critical parts also suffered from quality defects, such as incorrectly built leg assemblies.

Collins Aerospace cited post-COVID-19 supply chain issues, unreliable suppliers, and labor shortages as causing issues with its performance, while parts obsolescence is also contributing to difficulties. Vendors of certain parts may not make them anymore or even be in business. With only 18 EMUs ever built, of which 11 still existed in 2017, NASA is now low on certain critical spares to keep the EMU viable.

The prototype of a planned new spacesuit for low-Earth orbit operations. (Credit: Collins Aerospace)

The OIG report gave three recommendations to NASA. First, the agency should adjust award fees and include clear, objective criteria for the category covering technical performance, management, and health and safety compliance. The second recommendation was to align definitions in the award fee plan to reflect current federal acquisition guidance. Finally, the OIG recommended investigating alternative supply chain management strategies.

In 2019, the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel recommended replacing the EMU with a new spacesuit “before the risk to EVA becomes unmanageable”. After serious cost overruns and schedule issues with NASA’s own next-generation spacesuit development, the agency contracted Collins Aerospace to develop a new spacesuit for low-Earth orbit as part of the fixed-price Exploration Extravehicular Activity Services contract awarded in 2022.

Axiom Space was awarded the contract to develop lunar suits for Artemis landings under the same acquisition. While Axiom is still working on the lunar suits, Collins terminated its effort to develop the replacement ISS suit in June 2024. The termination was characterized as a “mutual agreement” between Collins Aerospace and NASA because the contractor could not meet the required timelines.

The first test of Axiom’s spacesuit with two units in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory. (Credit: Axiom Space)

Axiom Space’s AxEMU suit

Axiom Space is now the sole contractor working on next-generation spacesuits for NASA, while Collins Aerospace continues to maintain the existing EMU. The company is now working on suits for the Artemis program and for the ISS, with an Axiom preliminary design review for the ISS suit completed in December 2024. The preliminary design review for the lunar suit finished in March of that year.

Axiom and NASA were scheduled to complete a Key Decision Point review in the late summer of 2025. The company has scheduled its own critical design review for both Artemis III and an ISS demonstration by the end of this year or early next year. A joint NASA-Axiom critical design review is set for early 2026 as well.

Although Axiom Space has had its own issues, the company is currently testing its next-generation spacesuit design known as AxEMU. In August, Axiom announced that it had completed 700 hours of testing on the suit, and the company recently tested two suits during the same session at the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory pool at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Axiom and NASA are planning a vacuum chamber test for the new lunar suit — with a human inside the suit — in early 2026 as part of the critical design review milestone. The lunar suit will be used on Artemis III, currently scheduled to be humanity’s first lunar landing since Apollo 17 in December 1972, while the ISS suit will be scheduled for a demonstration in the future.

The Axiom lunar and ISS suits are nearly identical, with the key difference between the two suits being in the pressure garment. The ISS suit will also have interfaces compatible with the older interfaces on the Station, while the lunar suit will be compatible with the more modern interfaces aboard SpaceX’s Starship Human Landing System (HLS) lander.

A General Accounting Office (GAO) report in the summer of 2025 discussed the project’s top risks, including the suit not meeting certain NASA requirements, like the system exceeding its allowable mass and the allowable resource requirement of oxygen and water. Another risk the GAO report identified was the reliance on a sole contractor, much like NASA’s reliance on Collins Aerospace for the EMU.

While delays with the Starship human landing system project and the reopening of the Artemis III lander contract get public attention, the spacesuit is another key part of Artemis that must be ready before Artemis III can land on the lunar surface. Artemis III is officially scheduled to fly no earlier than the middle of 2027, but it is likely to be pushed even further toward the end of the decad

Quelle: NSF