29.11.2023

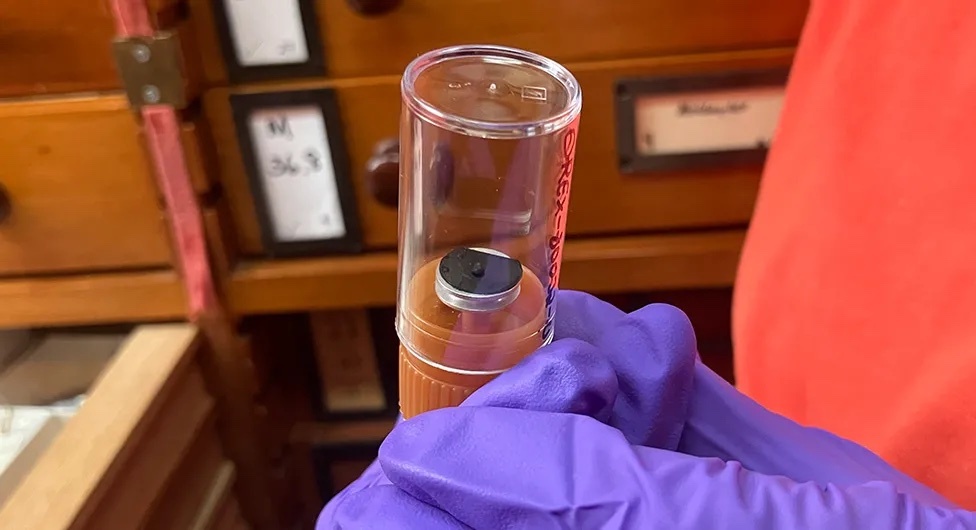

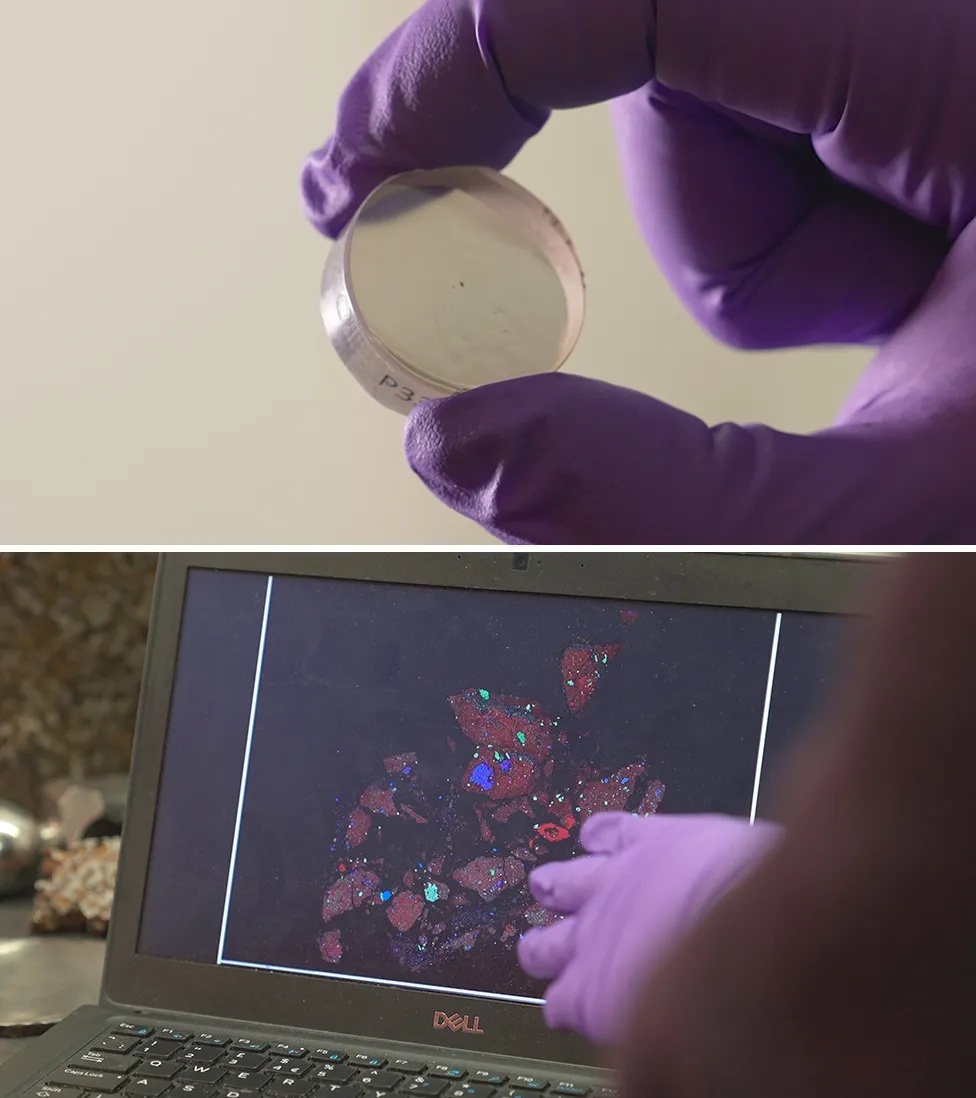

This fragment, little more than 1mm across, is packed full of information waiting to be extracted

Fragments from the asteroid US space agency Nasa has described as the most dangerous rock in the Solar System have arrived in the UK for study.

The tiny pieces of rock and dust from the object known as Bennu will be subjected to a battery of tests at the Natural History Museum, and the Open, Manchester and Oxford universities.

It is a small donation but ample, says the NHM's Prof Sara Russell.

"One hundred milligrams of beautiful" was how she described it to BBC News.

The sample was scooped up from the surface of 500m-wide asteroid Bennu in 2020 by Nasa's Osiris-Rex spacecraft, and then delivered by capsule to the Utah desert two months ago.

The US agency wants to learn more about the mountainous object, not least because it has an outside chance of hitting our planet in the next 300 years.

But more than this, the sample is likely to provide fresh insights into the formation of the Solar System 4.6 billion years ago.

This new knowledge will be found in the Bennu material's chemistry, which has remained largely unchanged over time.

Hundreds of scientists around the world are taking part in the investigation.

The NHM team, for example, has particular expertise in X-ray diffraction techniques (XRD).

These will reveal the types of minerals present, and their abundance.

"We're unusual in that we have an XRD set-up that allows us to do experiments that others maybe can't," explained the museum's Dr Ashley King.

"We also have an incredible minerals collection which means we have all the standards and can do the comparisons that will help us with our calculations."

Dr King has a number of instruments at his disposal at the west London institution, but he'll also be employing the biggest XRD machine in the country - the Diamond Light Source in Harwell, Oxfordshire.

The size of a football stadium, Diamond produces brilliant beams of X-rays to provide that next level of sensitivity and resolution.

Early analysis conducted at Nasa - assisted by Dr King - showed the black, extra-terrestrial Bennu material to be full of carbon and water-laden minerals.

That's a great sign. There's a theory that carbon-rich (organic), water-rich asteroids similar to Bennu may have been involved in delivering key components to the young Earth system. It's potentially how we got the water in our oceans and some of the compounds that were necessary to kick-start life.

Nasa has a lot more Bennu material in reserve and will archive most of it for future investigation

The 100mg given to the UK doesn't sound like a lot. The largest fragments are less than 2mm in diameter; some of the smallest are barely visible to the naked eye.

"It's only a teaspoonful, but if you imagine a teaspoon of sugar and how many individual grains there are in that - we are going to be looking at this material grain by grain," said Prof Russell, who leads the planetary materials group at the museum.

"It could be a lifetime of work ahead of us."

Nasa has much more in reserve.

The tiny encased speck (top) reveals its composition under an electron microscope (bottom)

Quite how much, it's not really sure.

It hasn't yet been able to open fully the Osiris-Rex sample container. An enclosing plate can't be unscrewed. The agency's curation team at the Johnson Space Center in Texas is having to qualify new tools to complete the job.

The UK's 100mg was sourced from 70g that had spilled from the container as it was being encapsulated for return to Earth. Seventy grams is actually 10g more than the minimum required of the mission when it was funded, so there is no rush to free the rest which may add a further 200g or so to the total.

Scientists in Britain and across the world hope to report on their early work at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) in March. Two major overview papers are also expected to be published at the same time or shortly after in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

Nasa plans to put most of the Bennu sample straight into the archive to preserve for future generations - for scientists who may not even have been born yet, to work in laboratories that don't exist today, using instrumentation that still awaits invention.