7.04.2022

Rocket Lab will try to catch a falling booster with a helicopter during a mission this month

The reusability milestone could come as early as April 19.

Rocket Lab used a helicopter to capture a falling Electron booster test article during a recovery test in early March 2020, as this screenshot from a company video shows. The company plans to catch a falling Electron booster during an orbital launch in April 2022. (Image credit: Rocket Lab)

Rocket Lab's next mission will feature some aerial action we've never seen before.

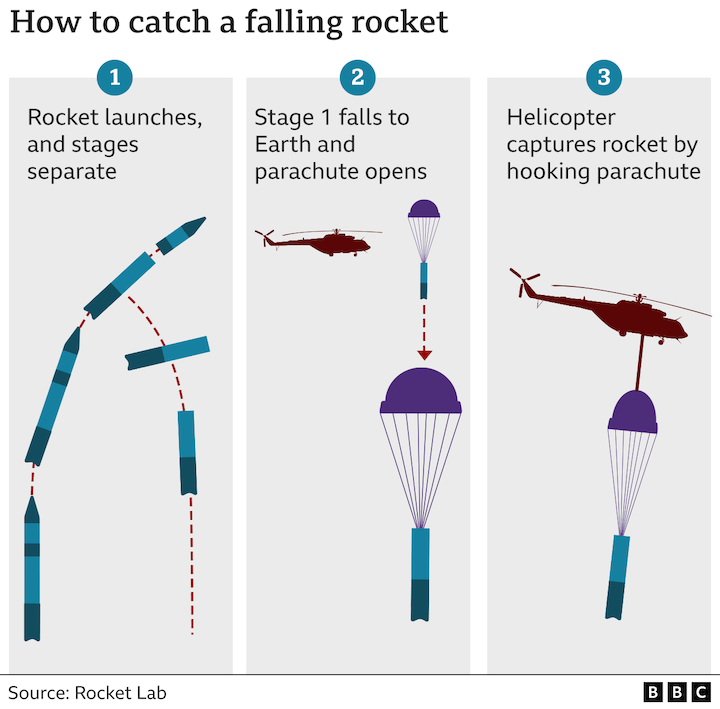

The California-based company is working to make its two-stage Electron rocketpartially reusable. The plan calls for snatching falling Electron first stages out of the sky with a helicopter shortly after launch — a dramatic step that Rocket Lab will attempt for the first time on its next mission, which is scheduled to lift off no earlier than April 19.

"We're excited to enter this next phase of the Electron recovery program," Rocket Lab founder and CEO Peter Beck said in a statement(opens in new tab) today (April 5).

"We've conducted many successful helicopter captures with replica stages, carried out extensive parachute tests and successfully recovered Electron's first stage from the ocean during our 16th, 20th and 22nd missions," he added. "Now it's time to put it all together for the first time and pluck Electron from the skies."

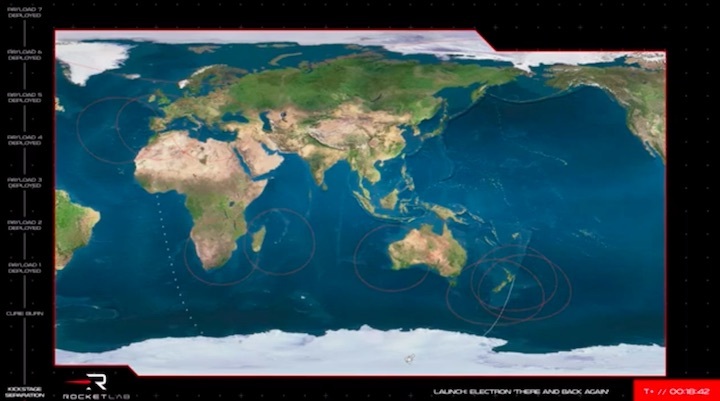

The upcoming mission, known as "There and Back Again," will launch from Rocket Lab's New Zealand site, on the North Island's Mahia Peninsula. It will be the 26th orbital flight overall for the 59-foot-tall (18 meters) Electron and for Rocket Lab.

The Electron's main job on "There and Back Again" is delivering 34 satellites to orbit for a variety of customers, but the booster's return to Earth may generate the most buzz and attention.

About an hour before liftoff, Rocket Lab will move a customized Sikorsky S-92 helicopter into capture position roughly 150 nautical miles (280 kilometers) off the New Zealand coast. If all goes according to plan, the Electron's two stages will separate about 2.5 minutes after launch; the second stage will continue powering the satellites to orbit, while the first stage will come back down to Earth.

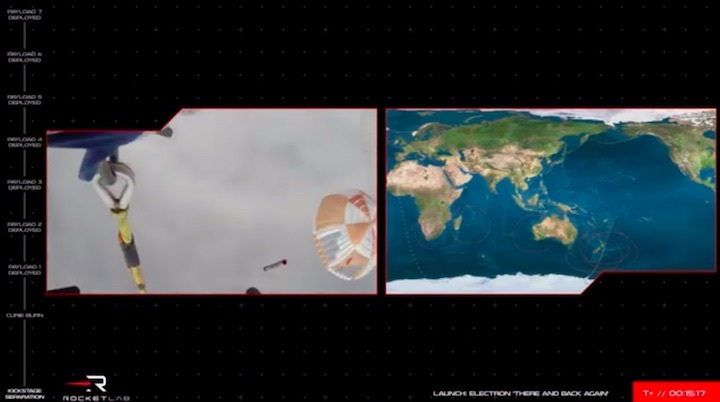

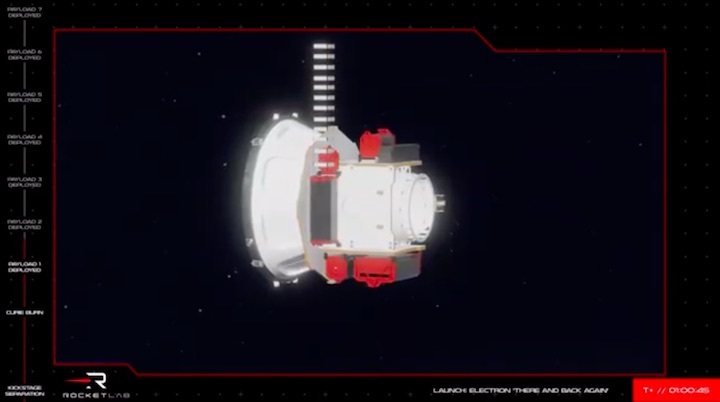

The booster will deploy a drogue parachute when it's about 8 miles (13 km) above the Pacific Ocean, then unfurl its larger main chute at an altitude of 3.7 miles (6 km) or so, Rocket Lab representatives said in the statement.

The chutes will slow the booster's descent velocity to about 22 mph (36 kph). That will be a manageable speed for the chopper, which will cruise in and try to grab the parachute line with a hook. The Sikorsky will then haul the booster back to land for analysis, including an assessment of its suitability for reuse.

There's no guarantee that Rocket Lab will ace this operation on its first attempt, of course.

"Trying to catch a rocket as it falls back to Earth is no easy feat. We're absolutely threading the needle here, but pushing the limits with such complex operations is in our DNA," Beck said. "We expect to learn a tremendous amount from the mission as we work toward the ultimate goal of making Electron the first reusable orbital smallsat launcher and providing our customers with even more launch availability."

Rocket Lab's Electron recovery strategy is quite different from that employed by SpaceX with its Falcon 9 rockets, which routinely make propulsive, vertical landings on terra firma or on ships at sea. The difference comes down to size: The Falcon 9 is much bigger than Electron and can therefore carry enough fuel to execute the mission and have the needed amount left over for landing burns.

Rocket Lab is developing a bigger launcher called Neutron, which is designed to be partially reusable from the outset. Neutron first stages will go the Falcon 9 route, making powered, vertical landings, Beck has said. Neutron is expected to fly for the first time in 2024.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 21.04.2022

.

Rocket Lab to launch HawkEye 360 satellites on first Wallops Electron mission

WASHINGTON — The long-delayed first launch of a Rocket Lab Electron rocket from Virginia is now scheduled for late this year, carrying satellites for HawkEye 360.

Rocket Lab announced April 19 it signed a contract with HawkEye 360 to deliver 15 satellites over three launches. Two of the launches will be dedicated flights, carrying six satellites each, while the third will carry three satellites on a rideshare mission with other customers.

The first of those launches, scheduled for no earlier than December, will be the first Electron launch from the company’s Launch Complex 2 on Wallops Island, Virginia. If that schedule holds, the launch will come three years after the company formally declared the launch pad complete. At that time a U.S. Space Force satellite called Monolith was going to be the first to launch from Wallops, but delays caused that satellite to launch from Rocket Lab’s New Zealand launch site in July 2021.

The delay in the first launch from Wallops has been due primarily to issues getting NASA certification of an autonomous flight termination system. That system, called the NASA Autonomous Flight Termination Unit (NAFTU), is required for Electron launches from Wallops.

“Encouraged by NASA’s recent progress in certifying its Autonomous Flight Termination Unit (NAFTU) software, which is required to enable Electron launches from Virginia, Rocket Lab has scheduled the mission from Launch Complex 2 no earlier than December 2022,” Rocket Lab said in a statement. A company spokesperson, asked if that launch date was driven by progress on NAFTU certification or customer readiness, said both were factors.

In January, NASA announced it had provided launch companies like Rocket Lab an advanced release of the NAFTU software with the expectation that the system would be certified as soon as February. The agency has not updated progress on NAFTU since then.

“My confidence level is high, but it was high last year, too,” Peter Beck, chief executive of Rocket Lab, said of launching from Wallops this year in an interview in February. “I would be extraordinarily disappointed if NASA doesn’t meet their deliveries to enable us to launch this year.”

Rob Rainhart, chief operating officer of Herndon, Virginia-based HawkEye 360, said the 15 satellites that will be launched on Electron will help reduce revisit times for its overall constellation of radio-frequency monitoring satellites, particularly in mid-latitude regions. “We’re excited to be joining the inaugural launch from Virginia, as a Virginia-based company launching our satellites from our home state,” he said in a statement.

Rocket Lab’s next mission is scheduled for no earlier than April 22 from New Zealand, carrying 34 satellites for various customers on a dedicated rideshare mission. The launch will be Rocket Lab’s next step toward rocket reuse, as it attempts to catch the booster, descending under parachutes, with a helicopter. A successful recovery would set the company up to attempt to reuse the stage on a future launch.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 3.05.2022

.

Rocket Lab - 'There And Back Again' Launch

The “There And Back Again” mission will see Electron deploy 34 satellites to a sun synchronous orbit for a variety of customers including Alba Orbital, Astrix Astronautics, Aurora Propulsion Technologies, E-Space, Spaceflight Inc., and Unseenlabs, and bringing the total number of satellites launched by Electron to 146. “There And Back Again” is also a recovery mission where, for the first time, Rocket Lab will attempt a midair capture of Electron’s first stage as it returns from space using parachutes and a helicopter.

Quelle: Rocket Lab

+++

Rocket Lab launches smallsats, catches but drops booster

WASHINGTON — Rocket Lab declared success in its effort to catch an Electron booster in midair after launch May 2, even though the helicopter had to release the booster moments later.

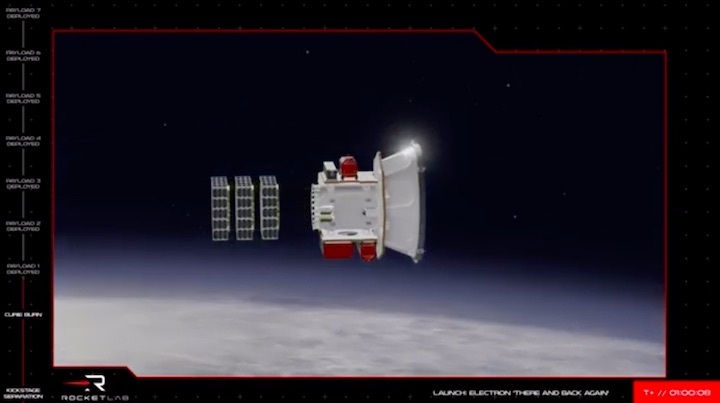

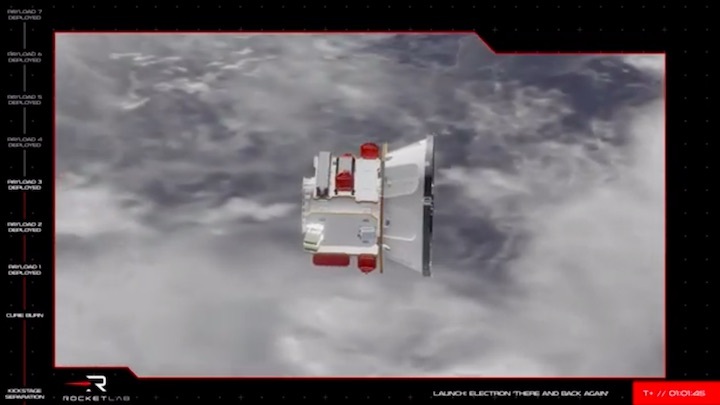

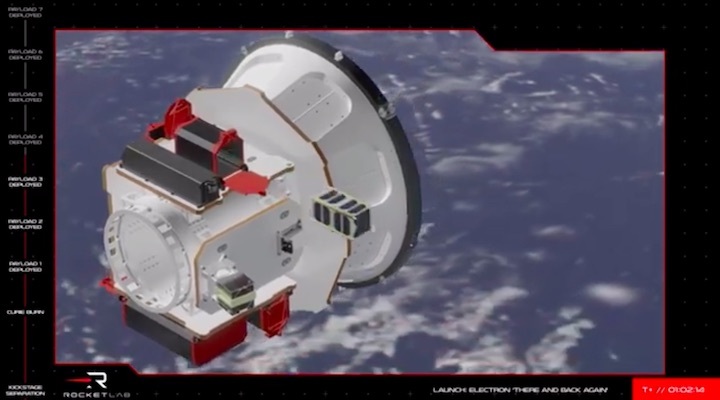

The Electron rocket lifted off from the company’s Launch Complex 1 in New Zealand at 6:49 p.m. Eastern after a brief hold in the countdown. The rocket’s ascent went as planned, with the kick stage, carrying a payload of 34 smallsats, reaching orbit about 10 minutes later.

On this mission, dubbed “There and Back Again” by Rocket Lab, the attention was on the rocket’s first stage. After three previous launches where the stage descended under a parachute to splash down in the ocean for recovery by a ship, the company planned to capture the stage in midair using a helicopter. A hook descending from the helicopter would grab the parachute, which would then return the stage to land or set it down on a ship without exposing it to salt water.

The company billed the midair capture as the final step in its efforts to reuse the stage. A successful midair recovery could allow the company to fly the stage again later this year, enabling the company to increase its flight rate without manufacturing more boosters.

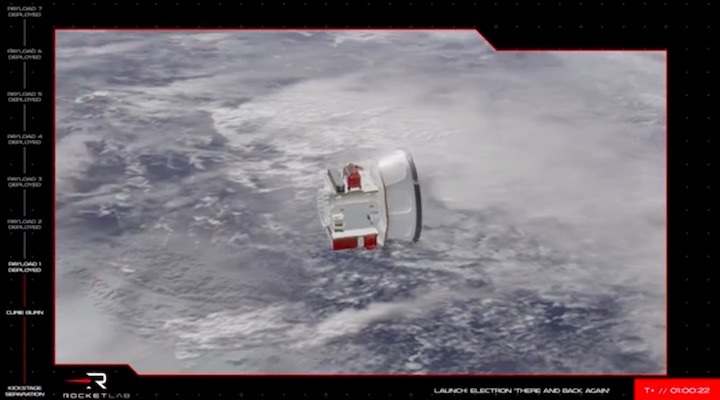

About 15 minutes after launch, the descending booster came into view of Rocket Lab’s Sikorsky S-92 helicopter. Video from the helicopter appeared to show the hook grappling the parachute to cheers from mission control. Moments later, though, there were groans and the webcast cut away, suggesting that perhaps the helicopter lost the booster.

More than a half-hour later, Rocket Lab confirmed that the helicopter had grappled, but then released, the booster. “After the catch, the helicopter pilot noticed different load characteristics than what we’ve experienced in testing,” company spokesperson Murielle Baker said on the webcast. “At his discretion, the pilot offloaded the stage for a successful splashdown” for recovery by a boat, like on the three previous recovery attempts.

Despite the release, she called the catch “a monumental step forward in our program to make Electron a reusable launch vehicle.” It was not clear when Rocket Lab would next attempt a midair booster recovery.

In a call with reporters four hours after liftoff, Peter Beck, chief executive of Rocket Lab, called the brief catch a “huge achievement” despite having to release the booster moments later. He said the company had not yet had a chance to debrief the pilots in detail about the catch attempt. “They got a great catch and they just didn’t like the way the load was feeling beneath the helicopter,” he said.

He said he believed it would be “trivial” for the company to determine why catching the actual booster was different from past tests using prototypes. “We’ll probably update our simulator to simulate the load accurately to what it was, go out and do a bunch of tests to get comfortable with the update load case,” he said, arguing that will be much easier than the effort needed to catch it in the first place. “That’s the hard thing.”

The booster splashed down softly in the ocean and was retrieved by a boat a short time later. “Obviously we don’t link tanking it and dunking it in the sea, but there’s still a tremendous amount of the stage and the equipment that we can reuse,” he said. He didn’t rule out trying to fly the stage again. “It’s still my hope that you’ll see this vehicle back on the pad again.”

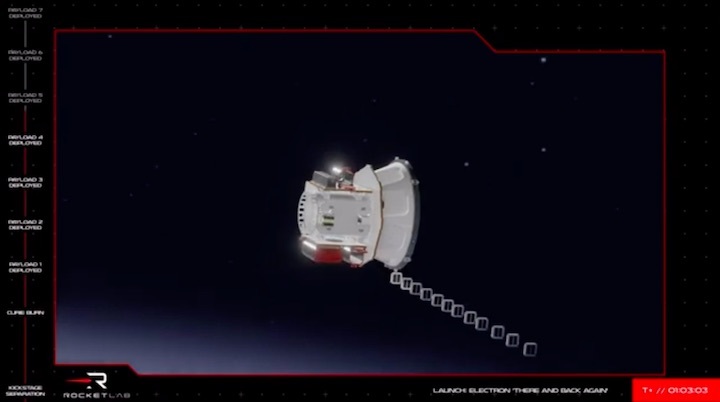

While the booster catch attempt captured attention for the launch, the primary purpose of the mission was to place 34 smallsats into a sun synchronous orbit at an altitude of 520 kilometers, which the kick stage completed an hour after liftoff. On this dedicated rideshare mission, 24 of the satellites were Spacebee satellites from Swarm Technologies, the SpaceX-owned company that operates a constellation for internet-of-things services, in a launch arranged by Spaceflight.

Also on the launch were three prototype satellites built by E-Space, a startup established by OneWeb founder Greg Wyler, that will test technologies for a future broadband constellation. Alba Orbital flew four small satellites for itself and various customers.

Unseenlabs had its BRO-6 satellite for location radio-frequency signals. Aurora Propulsion Technologies launched its AuroraSat-1 spacecraft to test debris removal technologies. A New Zealand startup, Astrix Astronautics, included a technology demonstration payload called Copia that will remain attached to the kick stage.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 4.05.2022

.

Rocket Lab: Helicopter catches returning booster over the Pacific

The US-New Zealand Rocket Lab company has taken a big step forward in its quest to re-use its launch vehicles by catching one as it fell back to Earth.

A helicopter grabbed the booster in mid-air as it parachuted back towards the Pacific Ocean after a mission to orbit 34 satellites.

The pilots weren't entirely happy with how the rocket stage felt slung beneath them and released it for a splashdown.

Nonetheless, company boss Peter Beck lauded his team's efforts.

"Bringing a rocket back from space and catching it with a helicopter is something of a supersonic ballet," the CEO said.

"A tremendous number of factors have to align and many systems have to work together flawlessly, so I am incredibly proud of the stellar efforts of our recovery team and all of our engineers who made this mission and our first catch a success."

Mr Beck said the hard parts of rocket recovery had now been proven and he looked forward to his staff perfecting their mid-air technique.

The entrepreneur later published a picture of the rocket stage after it had been picked up by a ship. It was intact and appeared to have coped extremely well with the heat that would have been generated on the descent through the atmosphere.

Today, only one company routinely recovers orbital rocket boosters and reflies them. That's California's SpaceX firm, which propulsively lands its stages back near the launch pad or on a barge out at sea.

Re-using flight-proven boosters should reduce the cost of rocket missions, provided maintenance can be kept to a minimum. SpaceX says very little refurbishment work is required between flights of its Falcon vehicles.

Rocket Lab will have to demonstrate similar gains to make the practice worthwhile.

Rocket Lab launches its two-stage Electron vehicles from New Zealand's Mahia Peninsula.

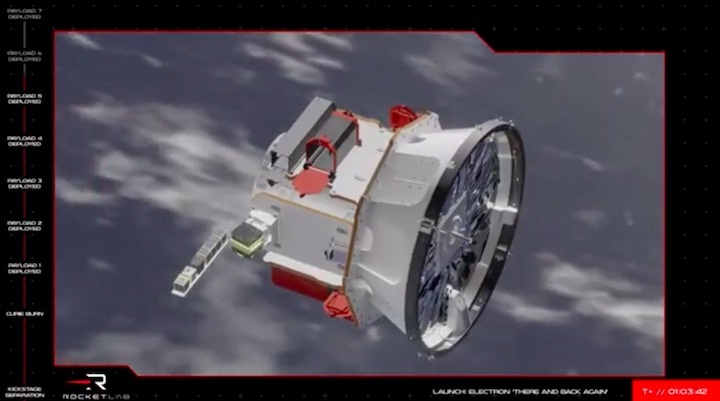

The first stage does the initial work of getting a mission off Earth, and once its propellants are expended falls back towards the planet.

The second, or upper, stage, completes the task of placing the satellite passengers in orbit with the help of a small kick-stage called Curie. Both the second stage and this Curie kick-stage eventually fall back into the atmosphere and burn up.

The first stage is given thermal protection as it plunges to Earth at speeds of almost 8,300km/h (5,150mph). Drag will take out much of this energy, before parachutes reduce the velocity to a mere 10m/s (22mph) to allow a Sikorsky S-92 to move in for capture.

Ordinarily, the helicopter would transfer the captured stage to land, but in this instance the pilots thought the load characteristics of the stage were sufficiently different to test flights that safety demanded they offload the booster to let it go into the water.

"I would say 99% of everything we needed to achieve today, we achieved; the 1% was the pilots didn't like the feel of it. So they jettisoned (the stage)," Mr Beck told reporters.

"And really, that kind of accounts for the amount of work we've got to do as well. Ninety-nine percent of the work is done, we'll figure out why the pilots didn't like it and go fix that."

Tuesday's mission, dubbed "There And Back Again", left the ground at 10:49 NZST (22:49 GMT, Monday).

Its primary objective was to take a diverse group of 35 spacecraft to orbit, more than 500km (310 miles) above the Earth. These payloads included four mini-satellites for Scottish manufacturer Alba Orbital, and three for E-Space, a new company started by serial space entrepreneur Greg Wyler.

Mr Wyler is well known in the space business and has been described as the "godfather of mega-constellations", the giant telecommunications networks now being developed by the likes of SpaceX, OneWeb and Amazon.

Mr Wyler founded OneWeb and before that, O3b, which sought to connect the unconnected (O3b stood for "other three billion", the number of people without an internet connection).

His new venture, E-Space, proposes to loft tens of thousands of satellites. But mindful of the congestion in orbit and the risk of collisions this might cause, the businessman claims his forthcoming constellation would also catch space debris and bring it out of the sky, leading to a net-positive impact on the space environment.