6.03.2022

In response to international sanctions, Russia’s space agency is distancing itself from its former partners and risks losing its role as a major space power.

ON FEBRUARY 24, the day Russian forces began their invasion of Ukraine, the Biden administration announced new sanctions, including ones that would “degrade” the Russian space program. Within an hour, Dmitry Rogozin, head of Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, posted a series of angry statements on Twitter. “If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit and fall on to United States or European territory?” he wrote in Russian, referring to the International Space Station, which Roscosmos plays a key role in operating.

Some experts subsequently dismissed his comments as bluster. “Rogozin is infamous for making rash statements like that,” says Bruce McClintock, head of the Space Enterprise Initiative of the Rand Corporation, a nonprofit research organization based in Santa Monica, California. “Things are ratcheting up though.”

While space activities might seem literally above the fray, that’s not truly the case. As the Ukraine war continues, the escalating tensions between Europe, the United States, and Russia are having consequences for space agencies: In addition to getting into disputes about the future of the ISS, Russia is withdrawing from a European Space Agency spaceport and delaying its ExoMars program. With the country’s budgets and revenue getting squeezed, Russia’s own space program now appears poised to decline. At the same time, US-based private space companies have seen their role in the conflict grow, which risks turning commercial spacecraft into military targets.

“By halting all these international cooperative efforts, Russia’s isolating itself. They’re cutting themselves off really badly,” says Victoria Samson, the Washington office director for the Secure World Foundation, a nonpartisan think tank based in Broomfield, Colorado.

It wasn’t always like this. The Soviet Union was a dominant space power at the beginning of the space race six decades ago. After the USSR collapsed, Roscosmos continued to play a major role, working with NASA and the ESA, even though most of the latter’s member countries are also part of NATO. All three agencies have been partners at the ISS since the 1990s. Russia has long operated one of the main segments of the station, and the newest modules to dock—including the Nauka science module—came from Russia just last year. After NASA retired the space shuttle program in 2011, the agency’s astronauts had to hitch rides on Russian Soyuz spacecraft to get to the station.

“That cooperation has survived many trials and turmoils in the past, but the situation is a bit different now,” says Todd Harrison, director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, DC-based think tank whose funders include aerospace companies and military contractors. Russia has been losing market share to US-based companies for selling rocket engines, launch services, and crew and cargo deliveries to the ISS. “They’re just as dependent on us; we’re not as dependent on them. And their economy has been in shambles for years and their space sector has been on the decline.”

But the war in Ukraine now strains—or may even sever—relationships between Russia and other spacefaring nations. On February 25, in response to European sanctions, Roscosmos announced it would “suspend cooperation” with the ESA’s spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana, where high-profile missions like the James Webb Space Telescope and the Planck space observatory have launched. They have withdrawn their workforce and halted Soyuz launches there.

Then the ESA announced that its ExoMars program will likely be delayed again. The latest stage of the mission involves bringing the Rosalind Franklin rover to the planet’s surface, where it will search for signs of past life. The rover’s launch had already been delayed once, and it was slated for a late September 2022 launch on a Russian Proton rocket at Russia’s Baikonur Cosmodrome spaceport in Kazakhstan. The next launch window to the Red Planet opens in late 2024. In response to WIRED’s interview requests, an ESA spokesperson said, “We are unable to comment on the crisis at the moment.” But the agency’s director general tried to take an upbeat tone in a public message on Twitter, saying “Notwithstanding the current conflict, civil space cooperation remains a bridge.”

Roscosmos also announced it will no longer supply rocket engines to the United States. “Let them fly on their brooms," Rogozin said on a state-owned Russian news channel.

But NASA is no longer totally dependent on Soyuz spacecraft to reach the ISS, and US companies are moving away from using Russian rockets. Since 2020, NASA astronauts have been flying upon SpaceX Crew Dragons. For years, the United Launch Alliance, a joint venture between Lockheed Martin and Boeing, has been using Russian-made RD-180 rocket engines for their first-stage Atlas 5 rocket—including for the new US weather satellite launched on Tuesday. But soon they will no longer be dependent on those as they develop their new Vulcan rocket, which will use BE-4 engines made by the US-based Blue Origin. The first batch of those new engines is scheduled to be delivered this year.

Northrop Grumman’s first-stage Antares rocket, however, uses Ukrainian fuel tanks and Russian RD-181 engines to supply the ISS with cargo aboard its Cygnus spacecraft. They likely won’t be able to do that much longer, as Russia will halt deliveries of those engines, according to a statement from Rogozin on a Russian state press site.

Even if current activities aboard the ISS continue as planned—NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei is scheduled to return to Earth aboard a Soyuz spacecraft later this month—the future of the station itself is in doubt. Roscosmos has not given any sign of being on board with NASA’s plans to extend operations past 2024, until 2030. Roscosmos also isn’t collaborating on proposed successors to the ISS, while NASA is investing in multiple commercial space station concepts. And Roscosmos hasn’t agreed to participate in NASA’s planned Gateway station, which will orbit the moon, support Artemis lunar missions, and later serve as a staging point for deep-space exploration.

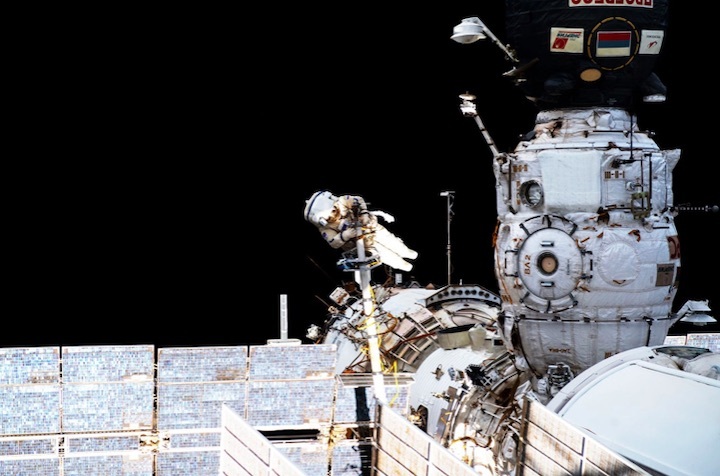

A Soyuz spacecraft and the Nauka science module with the Prichal docking module attached to the International Space Station.

PHOTOGRAPH: NASAWhile Russia’s space sector falls behind, the commercial space industry outside Russia has grown more powerful. And now, some of those private space companies have become actors within the Ukraine conflict. US-based companies Maxar Technologies, Capella Space, and Planet Labs have provided satellite imagery of war zones and buildups of Russian forces. The UK-based OneWeb had planned a launch of 36 internet satellites on a Russian rocket on March 4, but Rogozin said Roscosmos would proceed only if the company guarantees the satellites won't be used for military purposes and if the British government withdraws its stake in the company. Rather than agree to those demands, on March 3 OneWeb suspended that launch, plus all launches from the Baikonur spaceport. Elon Musk weighed in too, sending a truck full of SpaceX’s Starlink satellite dishes and user terminals to Ukraine, as some people, including the country’s vice prime minister, feared a loss of internet access.

But such involvement by SpaceX and satellite mapping companies could come with risks. “The commercial sector needs to think about this. The line between military and nonmilitary has been blurred,” Samson says. McClintock agrees, saying that commercial satellites could become military targets.

“Russia already has the full suite of counter-space capabilities,” Harrison says, referring to technologies that could be used against spacecraft. While Russia could shoot down a satellite with a missile, that’s the most extreme response, which would surely draw even more international condemnation. “The first level of attack—and this is something we already see them doing—is jamming communication signals to and from satellites,” he says. Russia also has the technical capability to accurately point a laser at a satellite’s sensor, temporarily blinding it or even damaging it, he adds. And Rogozin himself has been quoted as saying that hacking a Russian satellite would be considered an act of war, after a hacking group claimed earlier this week to have shut down Roscosmos’ satellite operations.

The other thing to watch is whether the Russian and Chinese space agencies become closer partners, Harrison says. The two countries have already agreed to work together on a lunar program to rival NASA and the ESA’s. But while in the past Russia aided China’s younger space program, it’s not clear what Russia could contribute at this point, he says. “China seems to be very tactical and pragmatic with the agreements that they make, and I don’t know that Russia has that much to offer anymore, especially after this,” Harrison says. “And there’s a lot of baggage that’s going to come with partnering with Russia from now on.”

Quelle: WIRED