25.01.2022

New space telescope reaches final stop million miles out

The world's biggest and most powerful space telescope has reached its final destination 1 million miles away

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. -- The world’s biggest, most powerful space telescope arrived at its observation post 1 million miles from Earth on Monday, a month after it lifted off on a quest to behold the dawn of the universe.

On command, the James Webb Space Telescope fired its rocket thrusters for nearly five minutes to go into orbit around the sun at its designated location, and NASA confirmed the operation went as planned.

The mirrors on the $10 billion observatory still must be meticulously aligned, the infrared detectors sufficiently chilled and the scientific instruments calibrated before observations can begin in June.

But flight controllers in Baltimore were euphoric after chalking up another success.

"We’re one step closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe. And I can’t wait to see Webb’s first new views of the universe this summer!” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement.

The telescope will enable astronomers to peer back further in time than ever before, all the way back to when the first stars and galaxies were forming 13.7 billion years ago. That's a mere 100 million years from the Big Bang, when the universe was created.

Besides making stellar observations, Webb will scan the atmospheres of alien worlds for possible signs of life.

“Webb is officially on station," said Keith Parrish, a manager on the project. “This is just capping off just a remarkable 30 days."

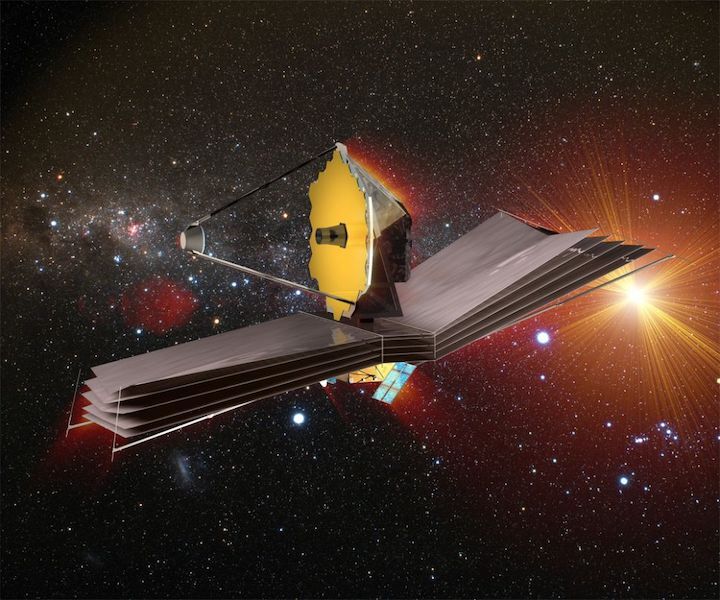

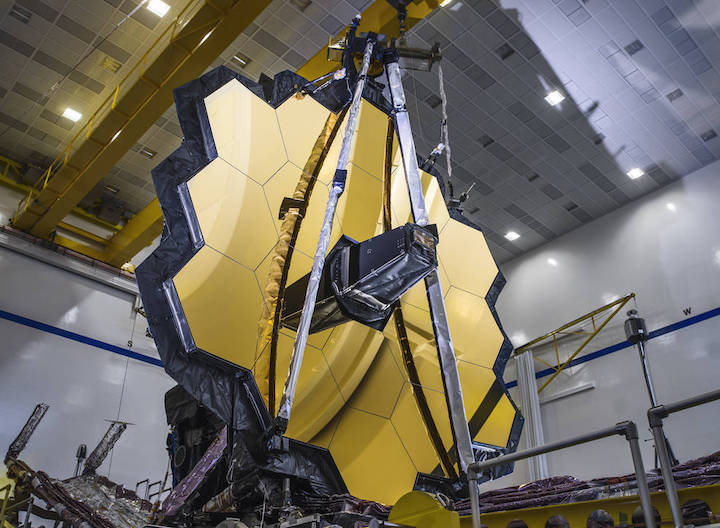

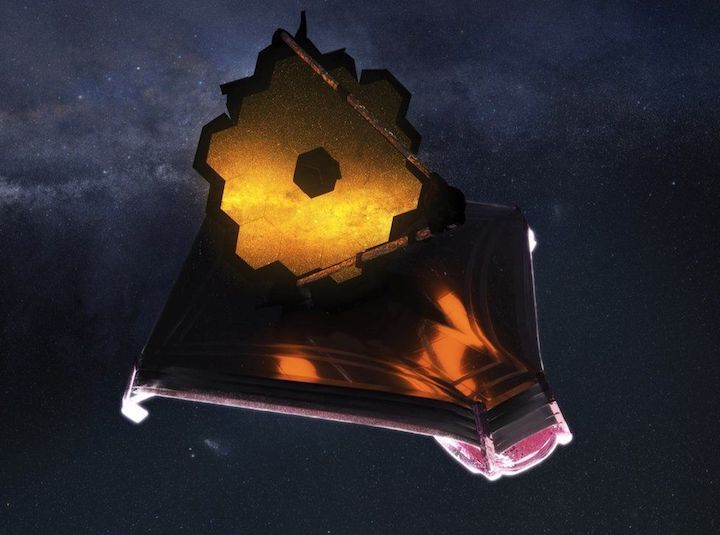

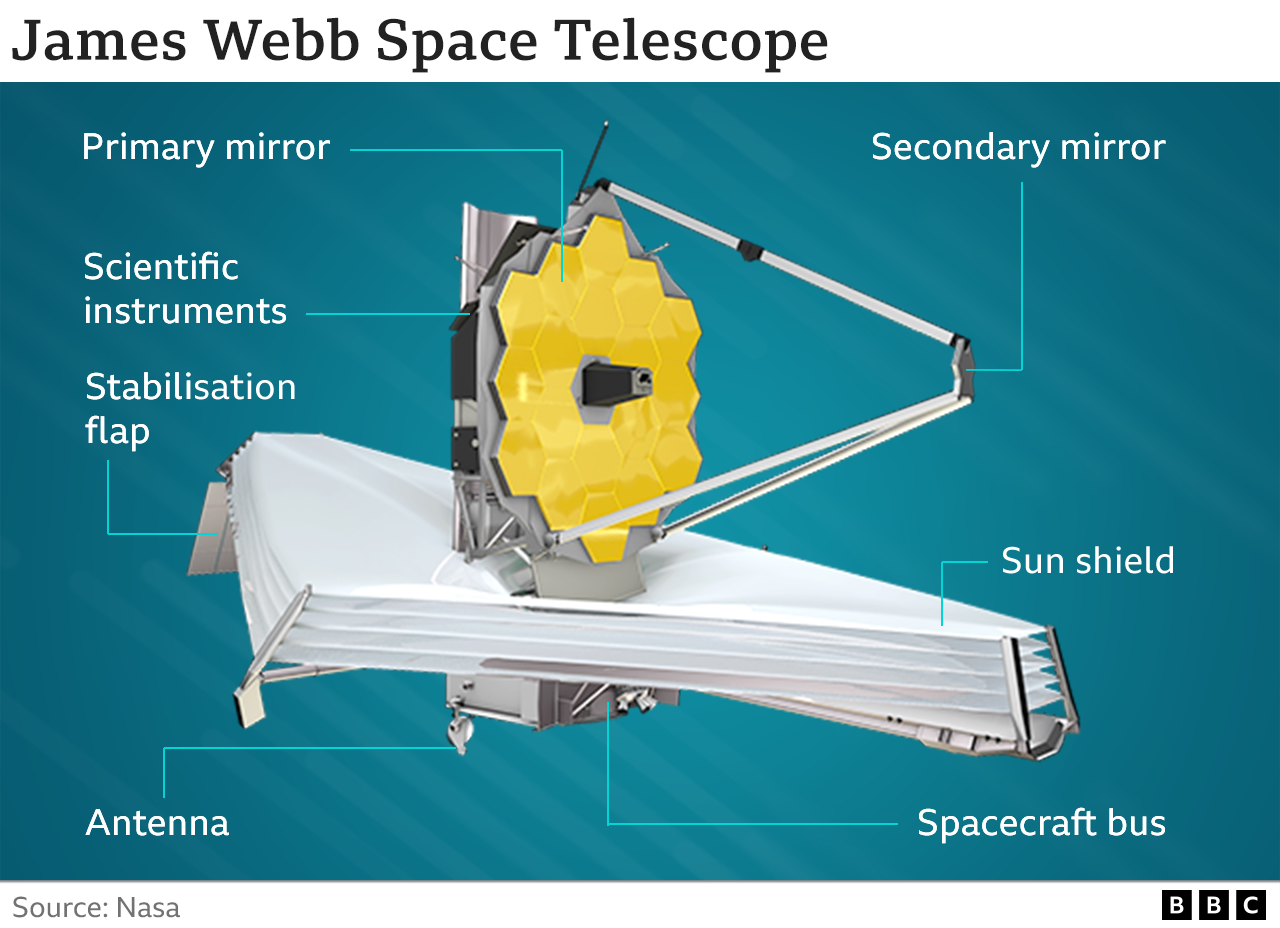

The telescope was launched from French Guiana on Christmas. A week and a half later, a sunshield as big as a tennis court stretched open on the telescope. The instrument's gold-coated primary mirror — 21 feet (6.5 meters) across — unfolded a few days later.

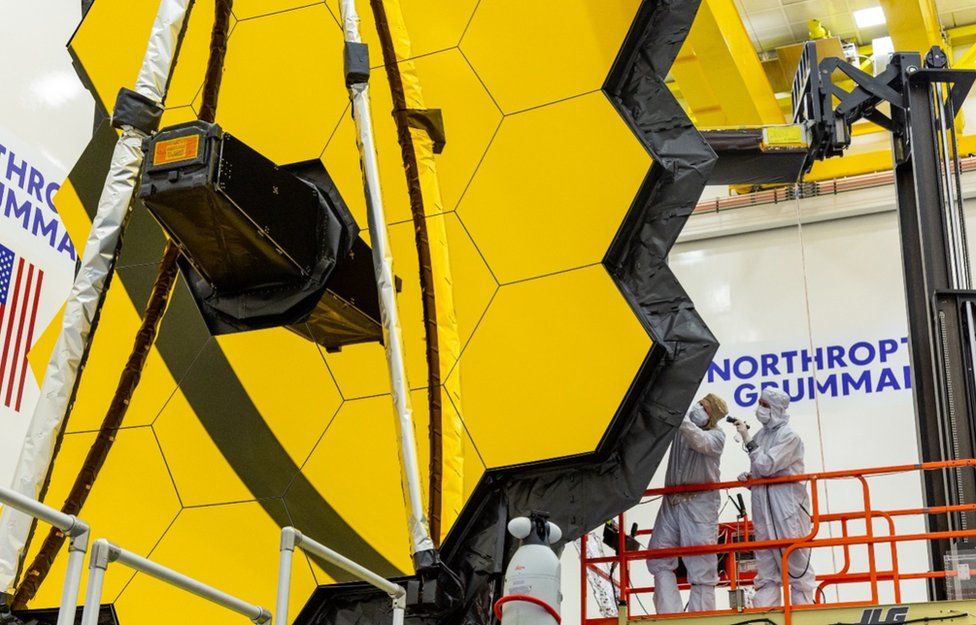

The primary mirror has 18 hexagonal segments, each the size of a coffee table, that will have to be painstakingly aligned so that they see as one — a task that will take three months.

“We’re a month in and the baby hasn’t even opened its eyes yet,” Jane Rigby, the operations project scientist, said of the telescope's infrared instruments. "But that's the science that we’re looking forward to.”

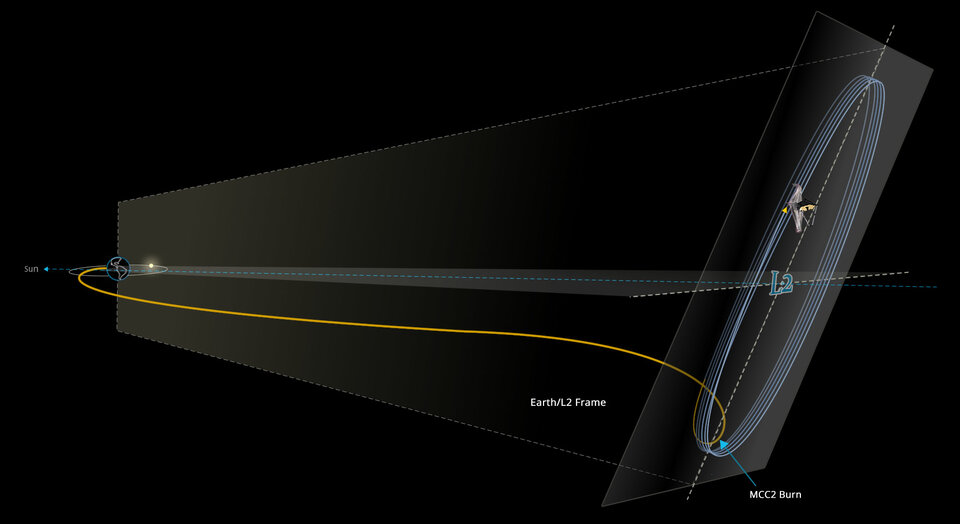

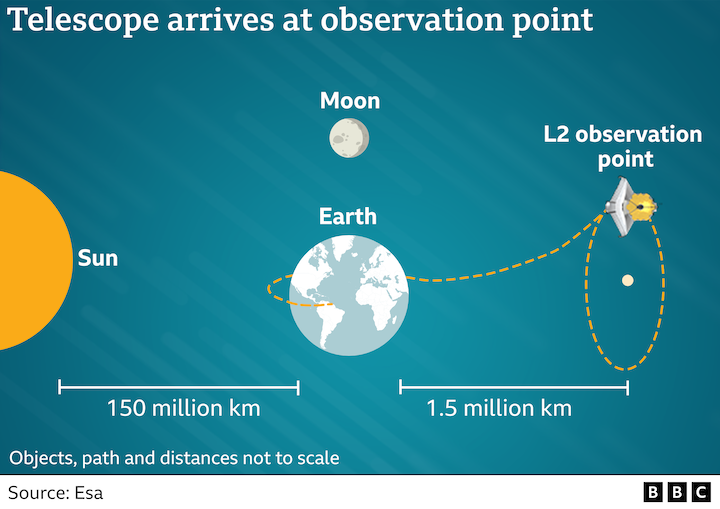

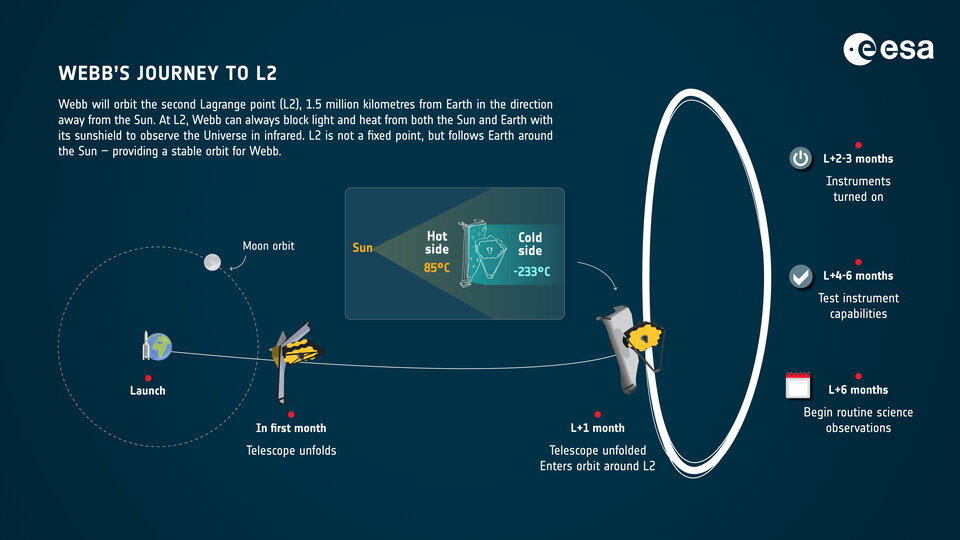

Monday's thruster firing put the telescope in orbit around the sun at the so-called second Lagrange point, where the gravitational forces of the sun and Earth balance each other. The 7-ton spacecraft will loop-de-loop around that point while also circling the sun. It will always face Earth’s night side to keep its infrared detectors as frigid as possible.

At 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) away, Webb is more than four times as distant as the moon.

The Webb is expected to operate for well over a decade, maybe two.

Considered the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which orbits 330 miles (530 kilometers) up, Webb is too far away for emergency repairs. That makes the milestones over the past month — and the ones ahead — all the more critical.

Spacewalking astronauts performed surgery five times on Hubble. The first operation, in 1993, corrected the telescope's blurry vision, a flaw introduced during the mirror's construction on the ground.

Whether chasing optical and ultraviolet light like Hubble or infrared light like Webb, telescopes can see farther and more clearly when operating above Earth's distorting atmosphere. That's why NASA teamed up with the European and Canadian space agencies to get Webb and its mirror — the largest ever launched — into the cosmos.

Quelle: abcNews

+++

James Webb telescope parked in observing position

Thirty days after it was launched, the James Webb telescope has arrived at the position in space where it will observe the Universe.

The Lagrange Point 2, as it's known, is a million miles (1.5 million km) from Earth on its nightside.

Webb was finally nudged into an orbit around this location thanks to a short, five-minute thruster burn.

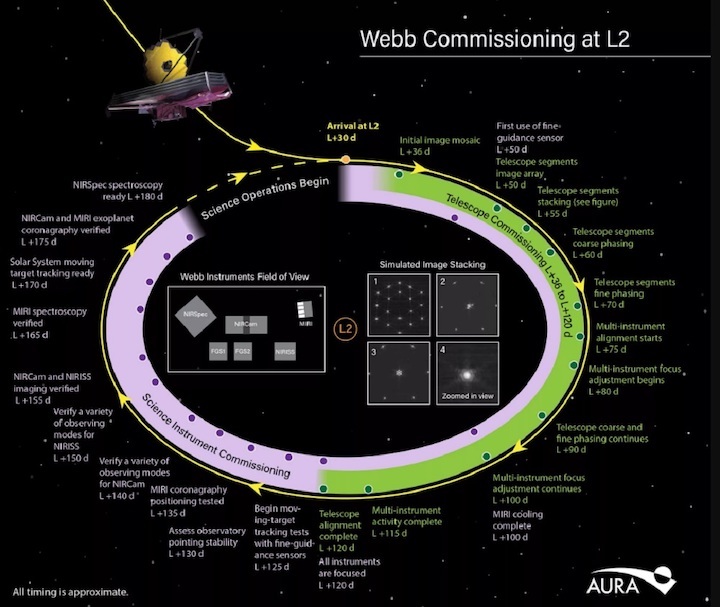

Controllers back on Earth will now spend the coming months tuning the telescope to get it ready for science.

Key tasks include switching on the observatory's four instruments, and also focusing its mirrors - in particular, its 6.5m-wide segmented primary reflector.

"There's a pretty intensive effort to take all of those 18 segments from their current state and get them to act as one big mirror, and also to get the secondary mirror into its optimised condition," explained Charlie Atkinson, the chief engineer on Webb at Northrop Grumman, the American aerospace company that co-led the telescope's development with the US space agency (Nasa).

"We do this using the science images, which is why we need to get the science instruments activated and checked out with some initial calibration work," he told BBC News.

Webb, billed as the successor to the famous Hubble Space Telescope, was launched on 25 December by an Ariane-5 rocket from French Guiana.

Its overarching goals are to take pictures of the very first stars to shine in the Universe and to probe far-off planets to see if they might be habitable.

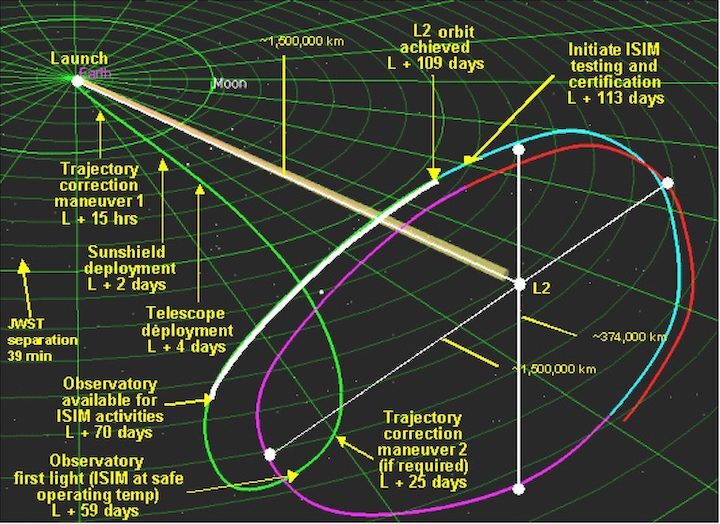

Europe's Ariane-5 gave the new observatory a near-perfect trajectory and velocity to get it out to L2. Even so, two course correction burns were necessary, with the third on Monday tipping Webb into its planned parking position.

The Lagrange Point 2 is one of five gravitational "sweet-spots" around the Sun and Earth where satellites can hold their position with few orbital adjustments, thus conserving fuel.

The other advantage is that Webb will not experience at L2 the big swings in temperature and light endured by space telescopes positioned much closer to Earth.

This is vital for the mission. It's designed to view the cosmos in infrared light and must maintain therefore constant super-cold conditions for its hardware.

Infrared light has waves that are just longer than those of visible light. "Seeing" in the infrared will allow the telescope to, for example, look through dust to image stars that would otherwise be obscured.

IMAGE SOURCE, NORTHROP GRUMMAN

IMAGE SOURCE, NORTHROP GRUMMANWebb will now circle L2, keeping the Earth and the Sun in a near-straight line.

"L2 is pseudo-stable," said Jean-Paul Pinaud, who leads the Northrop engineers that keep Webb on track.

"The flight operations team is preparing routine station-keeping burns. They'll be doing those every 20 days or so with the trajectory calculations provided by our flight dynamics team. We'll set them up in a similar way, and then fire the thruster. But the burns will be quite small."

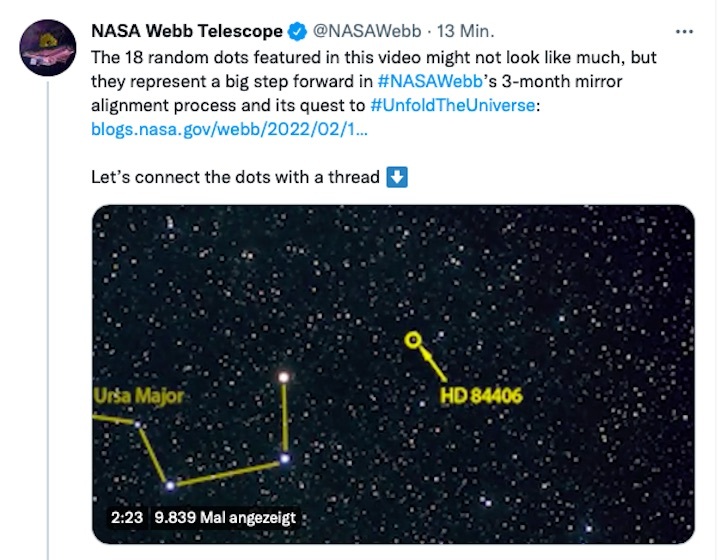

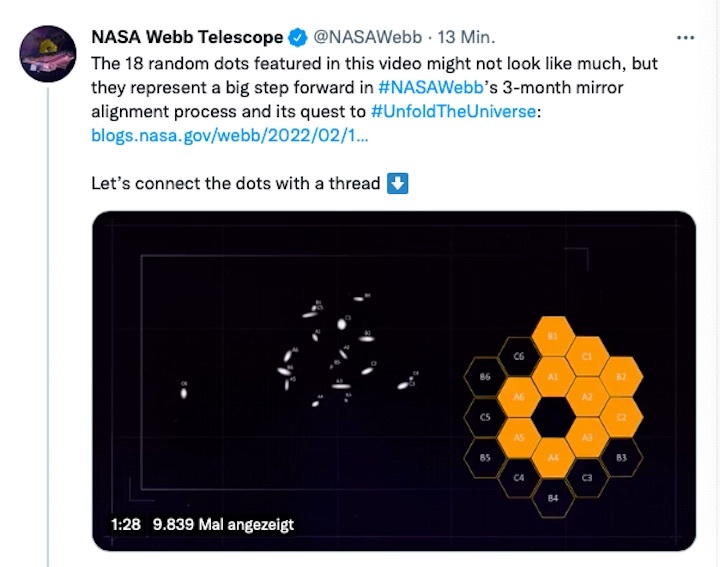

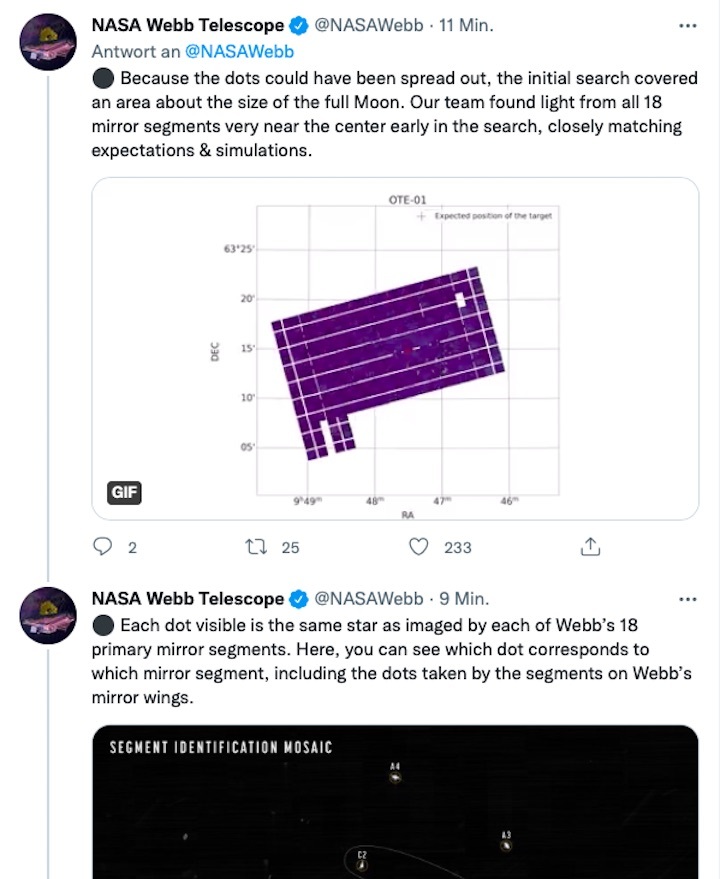

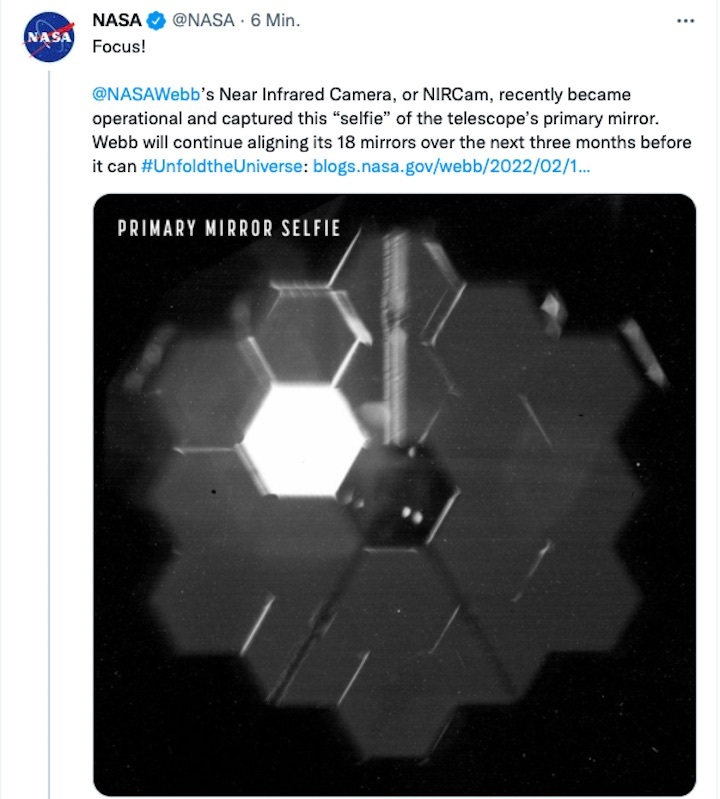

Hidden behind a big sunshield, Webb's optics and instruments will soon cool to about -230C (some sections of the telescope are already there). When that happens, controllers will switch on Webb's Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) to take a picture of a test star to begin the process of aligning the big mirror.

"We know when we first focus on a star in space, we'll actually see 18 different spots of light because the 18 individual mirror segments won't be aligned," said Nasa instrument systems engineer Begoña Vila.

"But we'll adjust the mirrors to bring all the spots together to make a single star that's not aberrated and good for normal operations.

"It's a long process. It can take up to three months during commissioning, and we are ready to do that," she told BBC News.

Focusing involves driving small actuators, or motors, on the back of the 18 segments of the primary mirror to harmonise their curvature. The current misalignment, which is measured in millimetres, will be brought down to one measured in nanometres - a factor of a million improvement.

Similar adjustments will be applied to the 74cm-diameter secondary reflector which sits out in front of the primary mirror and is used to bounce light back towards the instruments.

IMAGE SOURCE, ARIANESPACE

IMAGE SOURCE, ARIANESPACESo far, the Webb mission has not put a step wrong. The launch and journey out to L2 passed off without incident.

And even the complex business of unfolding the telescope after it came off the top of the Ariane rocket was made to look like the easiest of rehearsals.

"We were thrilled with the precision and success of all those deployments," said Kyle Hott, the mission systems engineering lead at Northrop.

"It's pretty incredible to think that it was all just a concept on paper decades ago, and now it's actually here, arriving at L2. Morale is high and we're so very excited."

Quelle: BBC

+++

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope reaches new home a million miles from Earth

After a nail-biting 29 days of travel and ultra-precise deployments, the James Webb Space Telescope fired its thrusters one more time Monday to reach its final parking spot a million miles from Earth.

"Webb, welcome home," NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement after a five-minute burn added just 3.6 mph to the telescope's speed. "Congratulations to the team for all of their hard work ensuring Webb’s safe arrival at L2 today."

L2 refers to a kind of stable orbit known as a Lagrange point. Technically, Webb is now orbiting the sun and is staying in line with Earth about a million miles away.

"We’re one step closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe. And I can’t wait to see Webb’s first new views of the universe this summer," Nelson said.

The arrival at L2 capped off a treacherous 29 days in which everyone involved in the $10 billion program — from scientists to NASA officials to companies involved in building the infrared telescope — readily admitted the technical challenges were daunting. Every single thing had to work perfectly in order to launch, deploy mirror segments, and reach its final position.

Mission partners NASA, the European Space Agency, and Canadian Space Agency described the process as "29 days on the edge." Officials before launch said there were potentially 344 points of failure during that period.

Moving forward, engineers will spend about three months aligning Webb's 18 gold-coated hexagonal mirrors to the final configuration.

Webb uses a massive, 21-foot primary mirror made up hexagonal tiles to study the cosmos. Its main capability is infrared observation, meaning it will be able to peer through obstacles like dust clouds to see the early phases of star formation. Scientists even hope to see the atmospheric compositions of promising far-off planets.

Webb is the successor to Hubble Space Telescope, which revolutionized science with the Hubble Deep Field that famously captured thousands of galaxies in a single image.

Total cost to NASA: $10 billion over its 25-year development history, which doesn't include costs incurred by ESA and CSA. Northrop Grumman was the prime contractor for the project while Lockheed Martin built the main infrared instrument known as Near Infrared Camera, or NIRCam.

The telescope took flight on Christmas Day with help from a European Ariane 5 rocket. The European Space Agency operates the liftoff site in French Guiana, a territory of France just north of Brazil.

Quelle: Florida Today

+++

THE JAMES WEBB SPACE TELESCOPE HAS ARRIVED AT ITS DESTINATION

Fully deployed, the James Webb Space Telescope arrived at its new home today, in a halo orbit around the Earth-Sun L2Lagrange point.

NASA’s newest space telescope has arrived at its new home in space. On Monday January 24th at 2:00 p.m. EST (19:00 UT), the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) fired its thrusters for five minutes, putting it into the start of a halo (Lissajous) orbit around the Sun-Earth (L2) Lagrange point 1.5 million km (almost a million miles) beyond Earth's orbit. Engineers reported that the telescope is in good health.

“Webb, welcome home!” said Bill Nelson (NASA-Administrator) in a recent press release. “Congratulations to the team for all of their hard work ensuring Webb’s safe arrival at L2 today. We’re one step closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe.”

They're not the only ones rejoicing. Amateurs and ground-based telescopes tracked JWST all the way to its destination:

THE PATH SO FAR

Launched on Christmas Day 2021 from the Guiana Space Center, JWST took just over 29 days to transit from Earth to L2. The Ariane 5 rocket launch was so accurate that less fuel than anticipated was required for the two planned mid-course correction burns. In fact, the rocket deliberately underpowered the launch by a small amount, so the observatory would not overshoot its target. (If it did, it would have had to rotate sunward to "put on the brakes," wasting precious fuel and exposing the optics to the Sun.) With the course correction burns complete, team engineers now estimate that JWST will have enough fuel to last well past its 10-year planned extended mission.

Fitting the 6.5-meter mirror observatory in the Ariane 5 rocket fairing necessitated the design of a telescope that could fold up in a stowed-away configuration for launch, then unfold once it was in space.

Along the way to L2, the observatory unfurled and tensioned its sunshield, unfolded its primary and secondary mirrors, and performed small correction burns, as controllers learned just how the telescope and components would react to the cold vacuum of space.

The controllers also issued the commands for 132 actuators on the primary and secondary mirrors to drive 18 mirror segments out of their stowed launch position for initial individual focusing and adjustment. They didn't move far — the primary segments moved only 12.5 millimeters. An additional 18 "radius of curvature" actuators drove out of their stowed launch position as well. These will bend the segments of the primary to give the parabolic mirror its initial curvature.

WELCOME TO L2

As an infrared telescope, the joint Canadian Space Agency/European Space Agency/NASA observatory must stay at a super-cold 40 kelvin (-233°C/-387°F) for scientific observations. The gigantic sunshield is crucial to keeping the observatory cold, as is the telescope's orbit: a a halo orbit around L2.

At L2, JWST will orbit the Sun in time with Earth, but 1.5 million km in the opposite direction from the Sun. This is the perfect location for an infrared space telescope, as it can stay permanently oriented away from the heat signatures of both the Sun and Earth.

“If Webb was exactly at L2, then it would be difficult to transmit data back to Earth, because there would be interference from the Sun,” says Heidi Hammel (NASA/GSFC). “This orbit also keeps the telescope out of the shadow of the Moon, as well as the Earth. Finally, this ‘halo orbit’ requires the least amount of fuel for ‘station-keeping’ (keeping the telescope in orbit there at L2).”

The potato chip-shaped orbit at L2 is meta-stable, meaning it has a saddle-shape gravity gradient similar to the balancing point on a ridge. Therefore, the telescope needs to use its thrusters for small station-keeping corrections once every three weeks to keep it in a six-month, 232,000 mile (374,000 km) wide orbit around L2.

WHAT'S NEXT FOR JWST

The telescope’s optics now need to reach their wavefront configuration, as the mirrors are moved in nanometer and micron increments to achieve alignment.

“The next major activity for Webb is the alignment of the primary mirror segments, so that they work together as one mirror,” says Hammel. “This long, complex process will likely take a few months. Throughout that time, the instruments (cameras and spectrographs) will continue to cool. After the optical alignment is complete, then the final commissioning of the instruments takes place.”

Expect to see the first light for James Webb around L+36 days (early February), with an initial calibration mosaic. It won't be pretty — yet. Further alignment will result in improved images, and we can expect the first science observations by this summer.

And you thought that collimating your Newtonian for a night’s worth of driveway observing was hard. Still, the deployment of JWST has gone by the numbers thus far. Now, it's time to get down callibration and commissioning in preparation for the ground-breaking science that JWST is set to deliver.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope

+++

Webb has arrived at L2

Today, at 20:00 CET, the James Webb Space Telescope fired its onboard thrusters for nearly five minutes (297 seconds) to complete the final post launch course correction to Webb’s trajectory. This mid-course correction burn inserted Webb toward its final orbit around the second Sun-Earth Lagrange point, or L2, nearly 1.5 million kilometres away from Earth.

The final mid-course burn added only about 1.6 metres per second – a mere walking pace – to Webb’s speed, which was all that was needed to send it to its preferred “halo” orbit around the L2 point.

Webb’s orbit will allow it a wide view of the cosmos at any given moment, as well as the opportunity for its telescope optics and scientific instruments to get cold enough to function and perform optimal science. Webb has used as little propellant as possible for course corrections while it travels out to the realm of L2, to leave as much remaining propellant as possible for Webb’s ordinary operations over its lifetime: station-keeping (small adjustments to keep Webb in its desired orbit) and momentum unloading (to counteract the effects of solar radiation pressure on the huge sunshield).

Now that Webb’s primary mirror segments and secondary mirror have been deployed from their launch positions, engineers will begin the sophisticated three-month process of aligning the telescope’s optics to nearly nanometre precision.

Webb is the largest, most powerful telescope ever launched into space. As part of an international collaboration agreement, ESA has provided the telescope’s launch service using the Ariane 5 launch vehicle. Working with partners, ESA was responsible for the development and qualification of Ariane 5 adaptations for the Webb mission and for the procurement of the launch service by Arianespace. ESA has also provided the workhorse spectrograph NIRSpec and 50% of the mid-infrared instrument MIRI, in collaboration with the University of Arizona. Webb is an international partnership between NASA, ESA and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

Quelle: ESA

----

Update: 31.01.2022

.