30.04.2021

SLS core stage arrives at KSC but faces “challenging” schedule

WASHINGTON — The final major element of the first Space Launch System rocket arrived at the Kennedy Space Center, but NASA’s acting administrator says it will be “challenging” to launch the rocket before the end of this year.

The barge Pegasus arrived at KSC April 27 with the core stage of the SLS on board. Pegasus transported the core stage from the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi, where it had been since early 2020 for the Green Run test campaign that culminated in a full-duration static-fire test March 18.

NASA will transport the core stage to the Vehicle Assembly Building, where workers will attach to it its two five-segment solid rocket boosters, upper stage and Orion spacecraft. It will then be rolled out to Launch Complex 39B for final tests and, ultimately, the Artemis 1 launch.

“With the delivery of the SLS core stage for Artemis 1, we have all the parts of the rocket at Kennedy for the first Artemis mission,” John Honeycutt, SLS program manager at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, said in a statement.

That launch is notionally scheduled for late this year, although NASA has not provided an updated launch date for the uncrewed test flight. The NASA statement about the arrival of the core stage at KSC did not mention its launch date.

NASA Acting Administrator Steve Jurczyk, speaking at an April 27 Space Transportation Association webinar, said the plan is still to launch Artemis 1 before the end of the year. “We’re still trying our best to get that launch off by the end of this calendar year,” he said. “That will be challenging given some of the delays that we had.”

Those delays, he said, include the technical challenges suffered by the core stage during the Green Run tests, as well as those caused by weather and the pandemic. Jurczyk said later that those issues consumed nearly all of the margin in the schedule for a launch this year.

“The schedule for Artemis 1 will be really challenging,” he said. “If things go really, really well on integration of SLS and integrating Orion on the mobile launch platform and rolling out, we have a chance to launch by the end of the calendar year.”

“But this is first-time flow on a vehicle at KSC,” he added, meaning that this is the first time they have gone through the steps of assembling the vehicle components and going through prelaunch processing. “We’ll undoubtedly encounter some challenges, so we don’t have a lot of schedule reserve against launching by the end of the calendar year.”

“If we can hit those major milestones and make progress, we’ve got a shot,” he said. “If we start missing those milestones, then may have to think about whether we can make it this year or not.”

Bill Nelson, the Biden administration’s nominee to be NASA administrator, hinted at his confirmation hearing April 21 that the launch might slip to next year. “The first of the Artemis mission launches within the next year,” he stated in the written version of his opening statement, a time frame that would extend into early 2022.

“At the end of the year, perhaps early next year, you’re going to see the largest rocket ever — most powerful — launched,” he said of SLS during the hearing. “It will be the workhorse on the program of going back to the moon and then on to Mars.”

Quelle: SN

+++

Final piece of massive moon rocket arrives at KSC

Mike Bolger has been waiting eight years for this day. On Thursday morning he watched the final part of the most powerful rocket in the world arrive at Kennedy Space Center.

“We’ve now got all the pieces. We’ve got the boosters, we’ve got the core stage showing up today. We’ve already got the second stage here and Orion. So, all the hardware is here. Really the spotlight turns to us and it’s our opportunity to put it all together,” he said.

The massive core stage, which arrived by barge from Mississippi, is the backbone of the Space Launch System, NASA’s deep space rocket built for human space travel. Built by Boeing, the core stage is over 200 feet long and houses the flight computers and avionics as well as the fuel that powers the stage’s four engines.

The SLS is slated to launch later this year on an uncrewed test flight as part of NASA’s Artemis program to send the first woman to the moon.

As head of NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems, Bolger oversees the team that gets the rocket ready for liftoff.

“It’s our Super Bowl moment if you will. It’s our time to charge down the field and to really make this happen,” he said.

Prior to its journey to Cape Canaveral, the core stage’s four engines were put to the test at NASA’s Stennis Space Center. The first full duration test fire in January aborted early due to conservative test parameters. Engineers ran the test again in March, that time igniting the engines for the full mission duration of eight minutes.

To make up time, the manufacturers of the engines, Aerojet Rocketdyne, hustled to process the engines as quickly as possible.

“Boeing gave us a challenge of 30 days and we beat that. We had refurbishments done and ready for shipment in 29 days,” said Bill Muddle, a lead engineer on the RS-25 engine program.

“We also worked with our crane teams on how to get it hooked up and how to get it picked up and over into high bay three," Bolger explained.

This time it’s for real.

Inside the VAB, twin solid rocket boosters stand at attention ready to be mated to the core stage. But first technicians will perform work on the thermal protection system before attaching it to the boosters.

When SLS is complete it will stand at 322 feet, taller than the Statue of Liberty, weigh 5.75 million lbs. and produce 8.8 million lbs. of maximum thrust, 15 percent more thrust than NASA’s first moon rocket, the Saturn V.

On Wednesday morning as the SLS core stage was entering Port Canaveral, Michael Collins, one of the Apollo 11 astronauts that flew on the Saturn V, passed away. Collins, along with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, made history when their spacecraft landed on the moon in 1969.

Bolger feels responsible for continuing their legacy of deep space exploration.

“I really do feel connected to those guys, I feel like they would be very proud,” he said. “If I were an Apollo astronaut looking at what we’re doing I would be really excited about the fact that we’re taking what they had done and building off that work. We’re taking it another step.”

One of the next big steps for SLS will be its rollout from the VAB to the launch pad when teams will perform a “wet dress rehearsal” running through an entire launch sequence.

“The first time it rolls out of the high bay, you can imagine the doors open, it rolling out and the enormity of this rocket is going to be absolutely breathtaking,” Bolger said

The first launch of SLS, called Artemis 1, will be an uncrewed orbital test flight. The second and third launches will include crew with the goal of landing on the moon by 2024.

Quelle: Florida Today

+++

Core of NASA’s first Artemis moon rocket towed into Vehicle Assembly Building

A decade in the making, the core stage for NASA’s first Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket rolled into the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center Thursday to join up with twin solid rocket boosters and an Orion capsule for an unpiloted test flight around the moon.

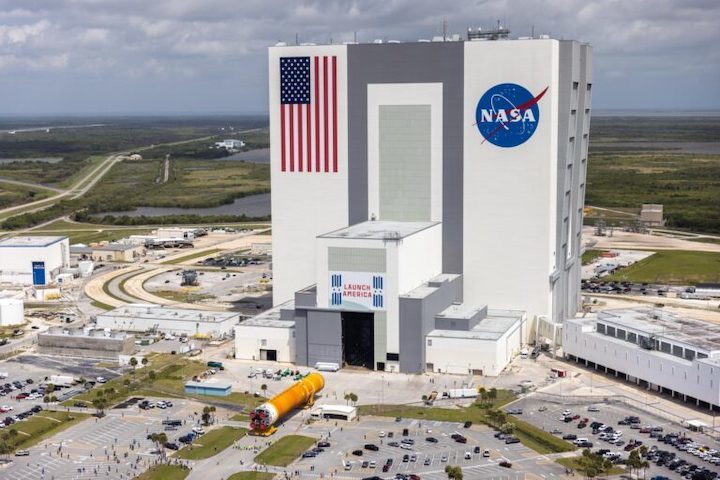

Clad in orange foam thermal insulation, the 212-foot-long (64.6-meter) rocket rolled off NASA’s Pegasus barge Thursday morning on a transport cradle driven by a self-propelled mechanism that carefully drove the core stage the nearly half-mile distance from the Turn Basin to the south door of the VAB.

Ground teams took their time with the operation, moving the rocket along at a glacial pace after an issue with the self-propelled transporter delayed the start of the offload from the Pegasus barge by about three hours.

Finally, the rocket emerged at around 8:30 a.m. EDT (1230 GMT) Thursday from the Pegasus vessel, a specially-designed barge that once hauled external fuel tanks for space shuttles from their factory in New Orleans to the Florida launch site. NASA extended the length of the barge to 310 feet (94.4 meters) to fit the longer SLS core stage.

The Boeing-built core stage measures 27.6 feet (8.4 meters) in diameter, the same width as the shuttle external fuel tank. The gigantic core stage contains reservoirs that will hold more than 730,000 gallons of super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants for launch.

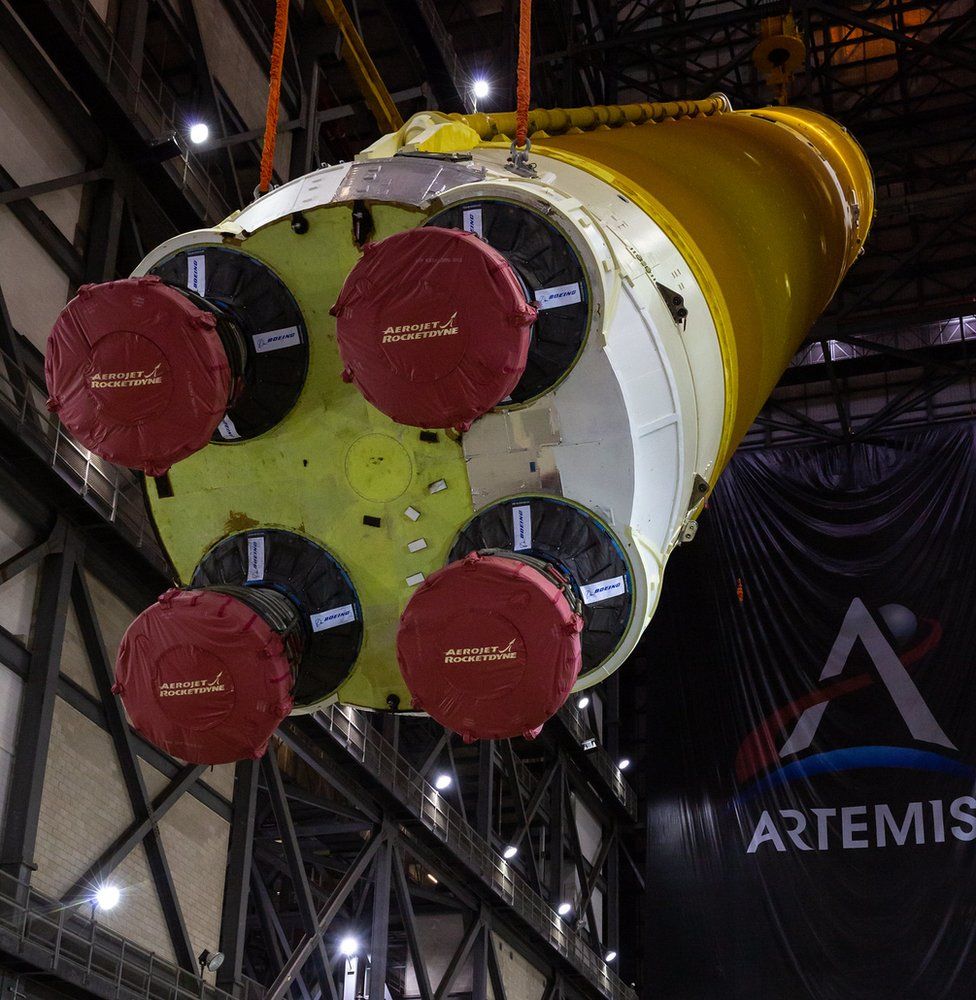

Four Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-25 engines are affixed to the rear of the core stage. All four engines are veterans of multiple space shuttle missions.

Engineers test-fired the four RS-25 engines for eight minutes March 18 at the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi, the same duration they will burn during a real launch. The hot fire was a final development test intended to iron out any glaring issues on the core stage before the first SLS test flight, known as Artemis 1.

Officials at Kennedy are eager to start working with the core stage inside the VAB. The two 177-foot-tall (54-meter) solid rocket boosters for the first SLS test flight, supplied by Northrop Grumman, are fully stacked on the rocket’s mobile launch platform in High Bay 3 inside the Vehicle Assembly Building.

With the core stage now at Kennedy, technicians will complete refurbishment of the rocket’s foam and cork insulation, which suffered some expected damage after the eight-minute RS-25 engine test-firing last month. Ground teams at Kennedy will also install ordnance to be used on the rocket’s flight termination system, which would activate to destroy the rocket if it flew off course and threatened the public during launch.

NASA aims to be ready by the end of May to rotate the rocket vertical and lift it by crane into High Bay 3. A crane operator will carefully lower the core stage in between the two SLS solid rocket boosters.

Workers will connect the core stage with each booster with braces at forward and aft attach points. Next will be stacking of the SLS upper stage, derived from the second stage used on United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4-Heavy rocket, and an adapter that will support the Orion spacecraft.

The rocket will be crowned with a mass model of the Orion spacecraft for structural resonance testing of the fully-stacked launch vehicle. Once that is complete, teams will move the real Orion spacecraft — already integrated with its launch abort system — to the VAB for attachment to the top of the Space Launch System.

The fully-assembled Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft will stand 322 feet (98 meters) tall. During launch, the rocket’s four RS-25 engines and twin solid rocket boosters will generate 8.8 million pounds of thrust. It can send about 59,500 pounds (27 metric tons) of mass to the Moon, more than any rocket operating today.

NASA plans to roll the Space Launch System out of the Vehicle Assembly Building for the first time as soon as August — but more likely in the fall — to travel to pad 39B for a countdown rehearsal. The launch team will load super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants into the rocket and practice countdown procedures.

After that is done, the rocket will return to the VAB for final checkouts and preparations, then will roll out to pad 39B again for launch.

Steve Jurczyk, NASA’s acting administrator, said Tuesday that the agency still hopes to launch the Artemis 1 test flight by the end of 2021.

But he acknowledged the schedule was “challenging” to pull off the launch this year. A delay of any major milestone would put the launch date in jeopardy and slip the Artemis 1 mission to early 2022.

A second SLS/Orion test flight in 2023 will carry three NASA astronauts and a Canadian crew member around the moon and back to Earth. That mission, Artemis 2, will be the first time humans travel beyond low Earth orbit since the final Apollo moon mission in 1972.

Future Artemis missions will send astronauts back to the moon, and eventually land the first woman and the first person of color on the lunar surface, according to NASA.

The agency says the Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft are critical to the Artemis moon program, alongside a commercial human-rated lunar lander being developed by SpaceX, and a mini-space station to be placed into orbit around the moon.

But the programs, particularly the SLS, have faced years of delays and billions of dollars in cost overruns.

NASA started initial work on the Space Launch System in 2011, then eyeing an inaugural launch in 2017. As of June 2020, NASA had obligated $16.4 billion on the SLS program since its inception, according to the agency’s inspector general.

Additional photos of the SLS core stage’s offload Thursday are posted below.

Quelle: SN

+++

The SLS core stage (orange) for the Artemis-I mission just before entering the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center, April 29, 2021. Credit: NASA

The SLS core stage with its four Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-25 engines (with red covers) on its way to the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center, April 29, 2021. Credit: NASA

SLS core stage inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center, April 29, 2021. Credit: NASA

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 12.06.2021

.

Ground teams begin process to hoist SLS core stage onto its launch platform

Technicians inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center began a delicate, multi-day task Thursday to lift the 94-ton core stage of the first Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket for mounting between two solid-fueled boosters already stacked for a test flight to the moon.

The stacking milestone begins a process that NASA officials say should culminate in a fully-assembled Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft as soon as August. If everything goes on a schedule, a major “if” for a brand new rocket with a history of delays, NASA could move the 322-foot-tall (98-meter) rocket to pad 39B on top of one its giant Apollo-era crawler-transporters in late September for a mock countdown and fueling test.

NASA hopes to launch the SLS and Orion crew capsule on an unpiloted test flight around the moon as soon as late November. The mission, known as Artemis 1, will last more than three weeks and pave the way for the next SLS/Orion mission, Artemis 2, to carry a four-person crew around the moon in 2023.

Artemis missions later in the 2020s will land astronauts near the south pole of the moon using commercially-developed lunar landers. In April, NASA selected a variant of SpaceX’s Starship, a reusable heavy-lift rocket being developed with majority private funding, to land the first Artemis crew on the moon.

But NASA plans to use the government-owned Space Launch System rocket and Orion capsule for the round-trip flight between Earth and the vicinity of the moon, where astronauts will transfer into a lunar lander, such as the Starship, for descent to the surface.

The lifting of the SLS core stage onto its mobile launch platform moves NASA closer to launch of the Artemis 1 test flight.

Two cranes began raising the 212-foot-long (65-meter) core stage off cradles Thursday inside the VAB’s transfer aisle, the cavernous central passageway between the building’s four rocket assembly bays.

The milestone signaled of the start of a slow motion process to lift the core stage high above the VAB floor and rotate the rocket vertical. Before dawn Friday, teams maneuvered the core stage vertical to allow ground crews to disconnect one of the cranes attached to the aft end of the rocket.

That left the rocket handing on a heavy-duty 325-ton to hoist it over the transom into the building’s northeast high bay.

The rocket’s twin solid rocket boosters, each standing 177 feet (54 meters) tall, are already stacked inside High Bay 3 on a mobile launch platform.

The crane will lower the 27.6-foot-diameter (8.4-meter) rocket stage between the two boosters. Once in position, the core stage will be connected to the boosters at forward and aft load-bearing attach points.

The entire lift and mate operation could take several days, according to a NASA spokesperson.

“When we start the lift up and over, it’s about a two-day process by the time we’re soft mated and disconnected,” said Cliff Lanham, senior vehicle operations manager for NASA’s Exploration Ground Systems division at Kennedy. “That includes everything to go up and over, attach to the boosters and be in a position where we say let’s go ahead and take the GSE (ground support equipment) off.”

During launch, the core stage’s RS-25 engines and twin solid rocket boosters will generate 8.8 million pounds of thrust. It can send about 59,500 pounds (27 metric tons) of payload to the moon, more than any rocket operating today.

The ground crew inside the VAB rehearsed the lift and mate procedures in 2019 with a pathfinder structure built to mimic the weight and size of the SLS core stage. But the last time the VAB cranes lifted real rocket hardware in preparation for launch was before the final space shuttle mission in 2011.

“The teams are going to be careful,” Lanham said in a recent interview with Spaceflight Now. “The teams are going to take their time and make sure they’re doing it right. It’ll seem glacial to the outside observer, but there will be a lot going on between inspections, making sure hookups are correct, and actually getting into the lift.”

The hoisting of the SLS core stage comes about six weeks after the rocket rolled into the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy, following an ocean journey aboard a NASA barge from the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Ground crews at Stennis test-fired the rocket’s four RS-25 engines for more than eight minutes in March to simulate a full launch profile.

Since the core stage arrived in Florida in late April, teams from NASA and Boeing, the rocket’s prime contractor, repaired dozens of areas of orange foam thermal insulation damaged during the eight-minute test-firing at Stennis. They also touched up cork thermal insulation on the bottom of the rocket’s engine section that charred during the hotfire test earlier this year.

The foam helps regulate temperatures inside the main stage’s cryogenic propellant tanks, which will hold more than 730,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen stored at minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 253 degrees Celsius) and liquid oxygen at minus 298 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 183 degrees Celsius).

Engineers also identified a few sensors that needed repair on the outside of the rocket. A small fraction of the more than 500 sensors designed to collect data the rocket’s performance and environments debonded during the test-firing.

And ground crews finished installing linear shaped charges along the core stage’s exterior. The charges are part of the flight termination system, which would destroy the rocket if it flew off course and threatened the public.

After completing all the work required while the rocket was horizontal, teams moved the core stage to the north end of the VAB’s transfer aisle Monday and installed a lifting cap, called the “spider,” on the forward end of the rocket.

After connecting two cranes to each end of the rocket, ground crews removed one of the two transporters underneath the core stage Thursday, leaving the rocket partially suspended over the floor of the transfer aisle.

Once teams rolled the other transporter out from under the rocket, the cranes lifted the core stage farther off the ground before rotating it vertical.

While technicians completed work on the rocket in the transfer aisle, teams inside High Bay 3 configured work platforms and readied the solid rocket boosters for mating with the SLS main stage.

With the core stage in place, Lanham said the pace of stacking will be be “fairly quick.” Next will be the Launch Vehicle Stage Adapter, or LVSA, the interstage structure that will connect the main stage with the rocket’s upper stage.

The LVSA is scheduled to be installed on top of the core stage next week.

Then the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion System, or ICPS, will be added to the Space Launch System later this month in High Bay 3. The hydrogen-fueled upper stage is derived from the second stage of United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4-Heavy rocket.

The upper stage is currently being readied for launch inside the Multi-Payload Processing Facility at Kennedy. When teams in High Bay 3 are ready, the ICPS will ride on a transporter several miles to the VAB to be raised atop the Space Launch System.

“It’s a pretty aggressive stacking sequence that we’ll be following, all in an effort to get us ready and get the umbilicals mated so we can get into our power up and get into our real big test, which will be our umbilical retract test,” Lanham said.

Once the upper stage is installed, ground teams will lift another adapter designed to connect the Orion capsule. Then a structure will go on top of the rocket to simulate the weight of the Orion spacecraft.

That will set the stage for a test to verify the propellant lines, fluid connections, and other umbilicals running between the mobile launch platform’s tower and the rocket can safely release and retract as they will at liftoff.

Then teams will move into structural resonance testing, or modal testing, of the fully-stacked launch vehicle in July. Once that is complete, teams will move the real Orion spacecraft — which will already be integrated with its launch abort system — to the VAB for attachment to the top of the Space Launch System, an event that could happen as soon as early August, Lanham said.

After the practice countdown, which NASA calls a wet dress rehearsal, the SLS and Orion spacecraft will return to the Vehicle Assembly Building for final closeouts, inspections, and ordnance connections.

The next time the rocket rolls out to pad 39B will be around six day before launch, Lanham said.

“We’ll face challenges ahead, he said. “We’re heading into hurricane season. We’ll see how that plays out. It’s the first time we’ve done this, so we’ll run into issues there, but we are absolutely trying to get this launched by the end of the year.”

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 14.06.2021

.

SLS: First view of Nasa's assembled 'megarocket'

Nasa has assembled the first of its powerful Space Launch System (SLS) rockets, which will carry humans to the Moon this decade.

On Friday, engineers at Florida's Kennedy Space Center finished lowering the 65m (212ft) -tall core stage in-between two smaller booster rockets.

It's the first time all three key elements of the rocket have been together in their launch configuration.

Nasa plans to launch the SLS on its maiden flight later this year.

During this mission, known as Artemis-1, the SLS will carry Orion - America's next-generation crew vehicle - towards the Moon. However, no astronauts will be aboard; engineers want to put both the rocket and the spaceship through their paces before humans are allowed on in 2023.

The SLS consists of the giant core stage, which houses propellant tanks and four powerful engines, flanked by two 54m (177ft) -long solid rocket boosters (SRBs). They provide most of the thrust-force that propels the SLS off the ground in the first two minutes of flight.

Both the core stage and the SRBs are taller than the Statue of Liberty, minus its pedestal.

Over Friday and Saturday, teams at Kennedy Space Center used a heavy-lift crane to first hoist the core stage, transfer it from a horizontal to a vertical position, and then lower it into place between the SRBs on a structure called the mobile launcher.

This structure currently resides inside the huge, cuboid Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB).

IMAGE COPYRIGHTNASA

IMAGE COPYRIGHTNASAThe mobile launcher allows access to the SLS for testing, checkout and servicing. It will also transfer the giant rocket to the launch pad.

Engineers began stacking the SRBs on the mobile launcher in November last year.

While this was going on, the core stage was attached to a test stand in Mississippi, undergoing a comprehensive programme of evaluation known as the Green Run.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTNASA

IMAGE COPYRIGHTNASAIn March, the core stage engines were fired successfully for around eight minutes - the time taken for the SLS to get from the ground to space - in the Green Run's final and most important test.

After refurbishment, the core was taken by barge to Kennedy Space Center.

Artemis-3, which will be the first mission to land humans on the Moon since Apollo 17 in 1972, should launch in the next few years. Nasa recently awarded the contract to build the next-generation Moon lander to SpaceX, which is adapting its Starship design for the purpose.

Quelle: BBC

----

Update: 19.06.2021

.

NASA's mega moon rocket now upright inside the VAB

Three months after arriving by barge, the massive core stage of NASA's moon rocket now stands upright inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center.

But how do you lift a 212 ft. long piece of hardware that weighs as much as a blue whale from horizontal to vertical and place it between two rocket boosters already in place?

In short: very slowly.

NASA released a time lapse video showing the core stage appearing to fly through the VAB and effortlessly inserted between the solid rocket boosters but the whole process actually took a few days.

To pull off this incredible engineering feat, five overhead cranes were used to lift and maneuver the over 188,000 pound core stage into place. The bright orange core stage is the backbone of the Space Launch System, NASA’s deep space rocket built for human space travel. Built by Boeing, the first stage houses the flight computers and avionics as well as the fuel that powers the stage’s four engines.