.

Strange bursts of radio waves from billions of light-years across the universe have puzzled astronomers for more than half a decade, making them question if the signal was even real. Now, in a paper published by the journal Science, researchers say they think they’ve figured out a potential explanation: Something cataclysmic.

What exact cataclysm is causing them, however – merging stars, dying stars, stars being eaten alive – is still up for serious debate.

The first of the four odd bursts was discovered about six years ago in the southern sky. The extremely bright beams would last for mere milliseconds – a fraction of the blink of an eye – and never reappear, leaving researchers at a loss to explain what was causing such mysterious, singular, blazing bursts.

These flashes were coming from a long way off too – which meant they must be powerful events, for their light to reach the Earth. Measuring the distance the light from these bursts had traveled, the scientists found that they had originated from when the Universe was around 6 billion to 9 billion years old – around half the age of the universe, which is 13.8 billion years old.

The scientists have thrown out a few possible explanations. It could be two neutron stars merging; it may be a magnetic neutron star, or magnetar, in its death throes; or perhaps it comes from a black hole having a very stellar meal as it rips a star apart.

In any case, the light from these events may actually reveal new insight into the nature of the intergalactic medium that the radio waves pass through – and it may even help them account for some of the "missing matter" in the universe.

"Further bright [fast radio burst] detections will be a unique probe of the magneto-ionic properties of the [intergalactic medium]," the authors wrote.

These bursts may also be more common than that first strange flash in the sky may have seemed; researchers think these distant "fast radio bursts" must be going off once every 10 seconds in the sky. It’s just a matter of staring at the right patch of the heavens, or getting a radio telescope to stare at an even bigger swath to raise the chances of catching a burst in the act.

Quelle: ScienceNow

.

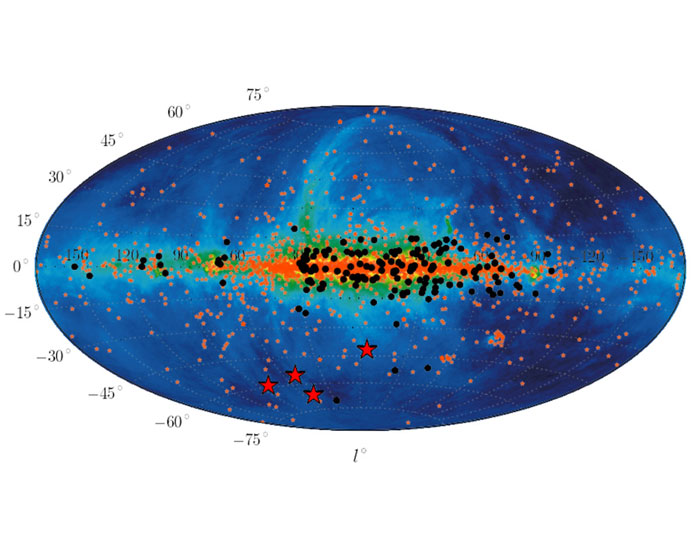

Four recently detected "blitzars" (red stars) have revealed that these sources of fleeting radio bursts are much more distant than known pulsars (black dots) (Image: C. Ng/MPIfR)

.

Brief and bright, fast and furious, uncommonly pure. Fast radio bursts have baffled astronomers since their discovery six years ago, but now they are revealing their true nature.

Two new studies suggest that FRBs are as common as dirt, that they produce more energy in a millisecond than the sun does in a million years, and that their single, intense flash of radio waves may be created when a neutron star is severed from its magnetic field as it collapses into a black hole. This explanation has also led to a more evocative name – blitzars – after the German word blitz for lightning.

In 2007, Duncan Lorimer and David Narkevic of West Virginia University in Morgantown discovered the first fast radio burst . Although many pulsars – spinning magnetic stars – give off brief periodic flashes of radio waves, the "Lorimer burst" was a singular event, lasting just a few milliseconds. What's more, it seemed to originate a few billion light years away, much more distant than the furthest pulsars that we can detect, suggesting that it must be exceptionally powerful.

The plot thickened in 2012 when Evan Keane, now at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, and his colleague detected a similar event.

Today Dan Thornton of the University of Manchester, UK, and colleagues have taken the total count to six in one fell swoop. In the journal Science, they report the discovery of four more FRBs using the 64-metre radio telescope in Parkes, Australia.

Sun outdone

With this many FRBs to observe, they were able to glean more details than previous studies did. The extent to which the radio waves are slowed by electrons in space reveals that they have travelled for billions of light years, confirming that FRBs are exceptionally powerful. The team concludes that they emit as much energy in a few milliseconds as the sun does in a million years.

Their comparative analysis also suggests that FRBs are frequent, with one being produced in every galaxy in the universe roughly every 1000 years. The fact that only six have been detected so far reflects their very short lifetime and the fact that astronomers can't keep an eye on the whole sky all the time.

So what could give rise to an FRB? Several ideas have been put forward, including a collision between neutron stars – the ultradense, magnetic remains of supernova explosions – but most theories fail to explain why FRBs emit purely at radio wavelengths. Other energetic cosmic explosions shine across a much broader spectrum, including in visible light, x-rays and gamma rays..

But another study, posted online today, details a scenario that can account for this. Heino Falcke of Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and Luciano Rezzolla of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Potsdam, Germany, suggest that an FRB occurs when the supernova explosion of a giant star leaves behind a compact neutron star that is slightly overweight.

Delayed collapse

The object's own gravity would cause it to collapse into a black hole, the researchers say, if not for the centrifugal effect of its fast rotation. But within a few million years, the interaction of the neutron star's magnetic field with the surrounding interstellar material slows the spin. Eventually, gravity wins and the star turns into a black hole after all.

"When the black hole forms, the magnetic field will be cut off from the star and snap like rubber bands," explains Falcke. "This can produce the observed giant radio flashes." By contrast, other types of radiation, which would come from the star itself rather than around it, cannot escape the gravitational collapse.

Thornton doesn't want to comment on Falcke and Rezzolla's idea before the paper has been accepted for publication in a refereed journal. "Our favourite explanation for FRBs is a giant burst from a magnetar – a highly magnetised type of neutron star," he says. These explosions are expected to happen more or less as frequently as the mysterious radio bursts.

But Falcke and Rezzolla have already coined the term "blitzar" to describe FRBs.

Quelle: Science

5657 Views