14.05.2020

Scientists are looking at Mars in a whole new way. That’s because a new analysis of a famous piece of the red planet has revealed something exciting: traces of nitrogen.

Nitrogen, together with organic molecules — carbon-rich molecules that are considered the building blocks of life as we know it — have been spotted in the Alan Hills meteorite, a new study suggests.

The Alan Hills sample was discovered in Antarctica in 1984 and is one of the largest, most famous meteorites from Mars. That’s because it sparked quite the controversy when it was first found. Some of the first analysis of the rock suggested that the sample contained microbial fossils. This led to rumors that scientists might have spotted their firsts signs of Martian life.

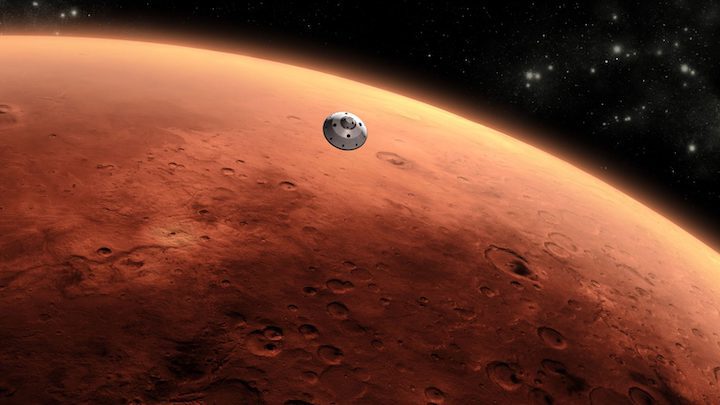

Over billions of years, Mars has been stripped of its atmosphere, and as such, its surface is subjected to cosmic radiation as well as blasts from interstellar objects. Sometimes the blasts are so powerful that chunks of rock are ejected into space and eventually land on other planetary bodies such as the moon or Earth.

Scientists estimate that the Alan Hills sample arrived on our planet at least 13,000 years ago and that the sample itself is around 4 billion years old. This 4-lb. chunk of rock is the oldest known meteorite from Mars that we’ve found.

Mars, as we know it today, appears to be a pretty inhospitable place for life. But that wasn’t always the case. Mars was once a lush, wet world, and new evidence points to the fact that an ancient chunk of the red planet is harboring traces of organic molecules.

These types of carbon-rich molecules are the building blocks of life. Their presence does not necessarily qualify as a definitive sign that life was once present on Mars, but it bolsters the case. That’s because this particular sample doesn’t just contain a random set of organic molecules; it contains traces of nitrogen explicitly.

And nitrogen is something that life here on Earth depends on.

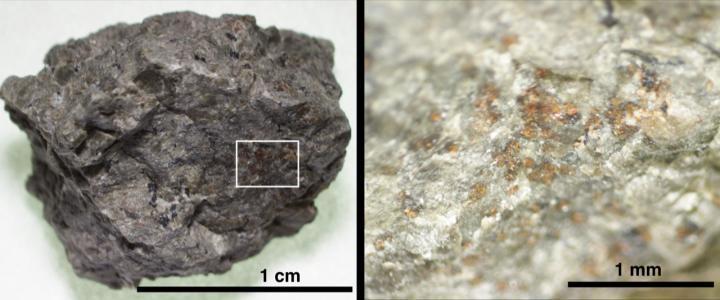

A rock fragment of Martian meteorite ALH 84001 (left). An enlarged area (right) shows the orange-colored carbonate grains on the host orthopyroxene rock. Credit: Koike et al. (2020) Nature Communications.

The Allan Hills 84001 meteorite is a famous hunk of Martian rock that was found in a region of Antarctica called Allan Hills in 1984. The new study, conducted by a group of researchers from the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA), indicates that not only does the sample contain nitrogen, but that the nitrogen was found within carbonate minerals in the rock. These types of minerals typically form in groundwater, so this could be further evidence to support the notion that Mars was once a wet world.

To make this discovery, the team from JAXA, led by Mizuho Koike, used a technique called X-ray spectroscopy to determine that the nitrogen was hiding in the carbonate minerals. Even though the Alan Hills sample has been in the news before, this was the first definitive evidence that there was nitrogen in the meteorite.

This discovery does not mean that the researchers have found signs of life on Mars. The presence of nitrogen and the carbonate minerals can be produced both biotically and abiotically. Scientists do not yet know how these molecules formed, but they have ruled out that they were somehow contaminated by Earth minerals.

But how were they formed? According to the researchers, there are two possibilities: either the organics originated on Mars, or they came from outside the planet. Mars was bombarded by comets and other rock and dust particles, and it’s possible that some of them may have been trapped inside the minerals as they formed.

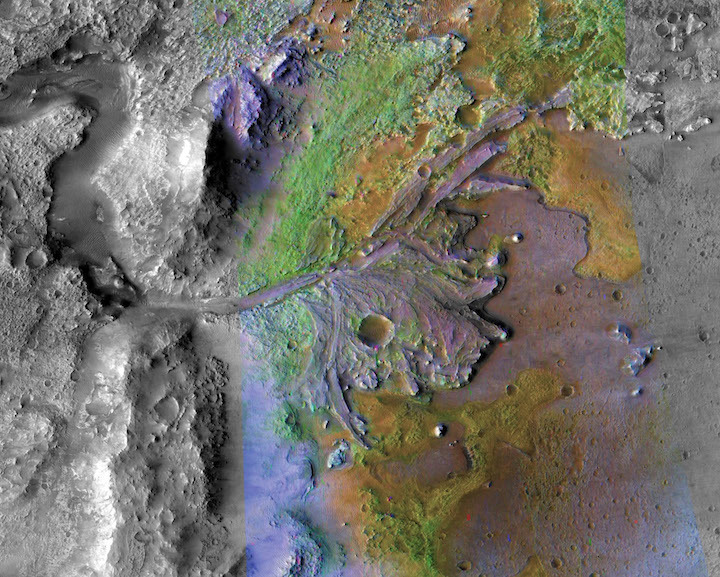

Researchers will soon have other Martian rocks to compare these results to. This summer, NASA is launching the Perseverance Mars rover. The six-wheeled robot will land in on Mars in a region called Jezero Crater. The agency selected this spot as the landing site because it’s believed to be an ancient river delta and could contain minerals known to preserve microfossils here on Earth.

The rover’s task will be to search for signs of a past life as well as to bag up samples that will be sent to Earth on later missions. Once researchers have access to pristine Martian samples, they will be able to expand their knowledge of the red planet. And perhaps even be able to tell if Mars ever hosted life.

Quelle: TESLARATI