9.11.2019

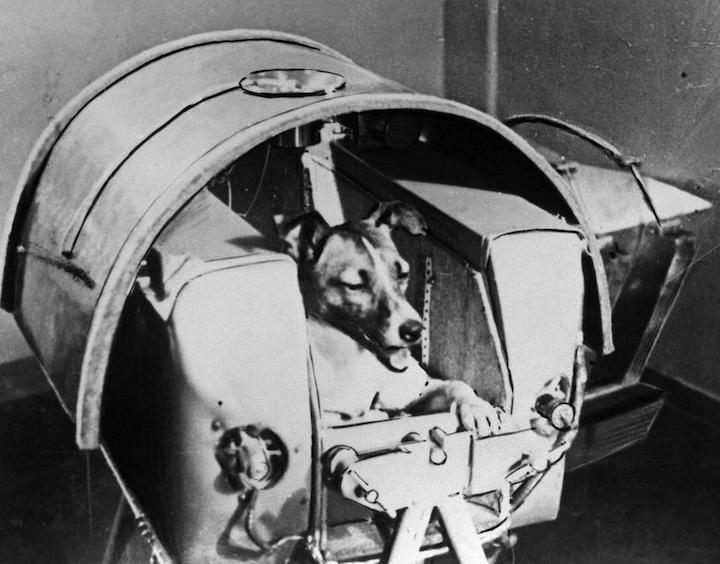

Laika, Russian cosmonaut dog, 1957. Laika was the first animal to orbit the Earth, travelling on ...

Laika was just a Moscow stray when she was drafted as a guinea pig for the Soviet Union’s launch of its Sputnik 2 spacecraft. The iconic photo in which her mongrel paws lazily grace the edge of her tiny metal carrier belies the fact that her first launch would be her last.

While Sputnik 2, which blasted into low-Earth orbit on November 3, 1957 was deemed a success, Laika was on a one-way trip. As NASA points out, she ‘expired’ a few hours after launch, even though the Sputnik 2 spacecraft didn’t burn up in Earth’s outer atmosphere until April 1958.

Thus, this week’s sixty-second anniversary of this poignant launch raises a real ethical question —- should we humans be sending animals into space? And even if they are sent up with all the precautions, is that a risk that they deserve having inflicted upon them?

Sergei Khrushchev, the late Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschev’s eldest son, told me in a 1998 interview that he was worried about what would happen to Laika. That he sympathized with the dog. But his father told him in so many words, Laika’s fate was inconsequential when looking at the larger picture of what the soviets deemed their mandate to conquer low-Earth orbit.

"My father's goal was to threaten Americans with death in the cheapest way," Sergei Khrushchev, who now lives in the U.S., told me in the February 1998 issue of the U.K.’s Geographical Magazine. "For him the [Soviet] R-7 ICBM was most important. We were defenseless against the Americans and their huge fleet of heavy bombers. But it was never our goal to destroy the US, and we didn't have the capability to make a first strike until the 1970s."

Even so, ground-based geopolitics and the notion that animals are expendable has been an attitude that has pervaded throughout the history of spacefaring nations’ forays into space.

Before humans actually went into space, one of the prevailing theories of the perils of space flight was that humans might not be able to survive long periods of weightlessness, NASA has noted. The American space agency points out that both American and Russian scientists utilized animals - mainly monkeys, chimps and dogs - in order to test each country's ability to launch a living organism into space and bring it back alive and unharmed.

“These early space missions were deemed too risky for humans and, in the case of Laika, were known to be a one-way trip,” Lori Marino, an evolutionary neurobiologist and president of The Whale Sanctuary Project, told me. There were also many monkeys, mice, cats, insects and even fish who gave their lives unwillingly so that we might explore space, she says. Most of these animals died either during or shortly after their flights or were deliberately killed afterwards, Marino notes.

On January 31, 1961, ‘Ham’ became the first chimpanzee to make it to sub-orbital space launched atop an American Mercury Redstone rocket; paving the way for the successful 1961 launch of Alan Shepard, Jr. —- America's first human astronaut, says NASA. Ham splashed down in the Atlantic some 60 miles from the recovery ship after his 16.5-minute flight, says the agency. And aside from suffering fatigue and dehydration was in good shape.

Even so, Marino says Ham was cruelly captured by animal trappers and ripped from his family at a very young age; subjected to 18 months of “training” in which he received electrical shocks to the soles of his feet. Then when he failed to respond correctly in tests, Marino says he had restraints placed on his neck, torso, and limbs for extended periods. He spent his remaining years in zoos, dying at the young age of 26.

Chimpanzee "Ham" in space-suit is fitted into the couch of the Mercury-Redstone 2 capsule

Yet NASA has a different take.

Without animal testing in the early days of the human space program, the Soviet and American programs could have suffered great losses of human life, says NASA. These animals gave their lives and/or their service in the name of technological advancement, paving the way for Humanity's many forays into space, it says.

But Marino disagrees. While we rightly laud the courage of human astronauts, she says, we need to remember that the path was paved for them by other animals who were not fortunate enough to reap the rewards of their service.

Does that also go for family pets who might want to follow their humans into space?

“Animals should not be taken into space, full stop,” said Marino.

Space travel in the near future is going to be, at best, severely uncomfortable and compromising for human astronauts, Marino notes. But while human astronauts know what they are getting into, other animals do not, she says.

“We do not have the right to put the lives of other animals at risk for our purposes,” said Marino.

Quelle: Forbes