6.11.2019

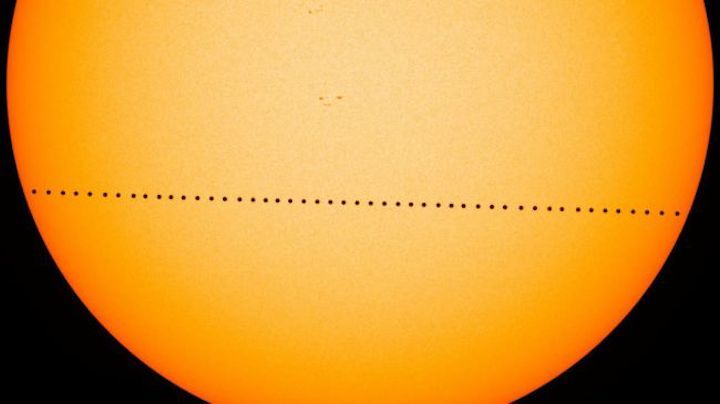

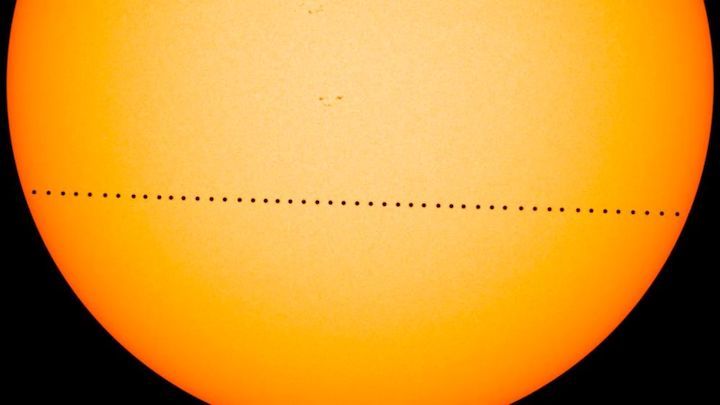

On Monday, Nov. 11, a most unusual event will take place: the transit (passage) of the planet Mercury across the sun's disk.

Such a sight is a relatively rare occurrence as seen from Earth. From our perspective, only transits of Mercury and Venus are possible. This event will be the fourth of 14 transits of Mercury that will occur during the 21st century. In contrast, transits of Venus occur in pairs, with more than a century separating each pair.

Mercury will take nearly 5.5 hours to cross in front of the sun. The transit will be widely visible from most of the Earth, including the Americas, the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, New Zealand, Europe, Africa and western Asia. It will not be visible from central and eastern Asia, Japan, Indonesia and Australia.

The transit begins before sunrise for observers in western North America. On a map of the United States, draw a line from roughly Lake Charles, Louisiana, to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Anywhere to the west of that line will have Mercury already silhouetted against the sun's disk as it rises that morning. The transit ends after sunset for Europe, Africa, western Asia and the Middle East, with Mercury still on the sun's disk as it vanishes below the west-southwest horizon.

The entire transit will be visible from start to finish over eastern North America, Central and South America, southern Greenland and a small slice of West Africa.

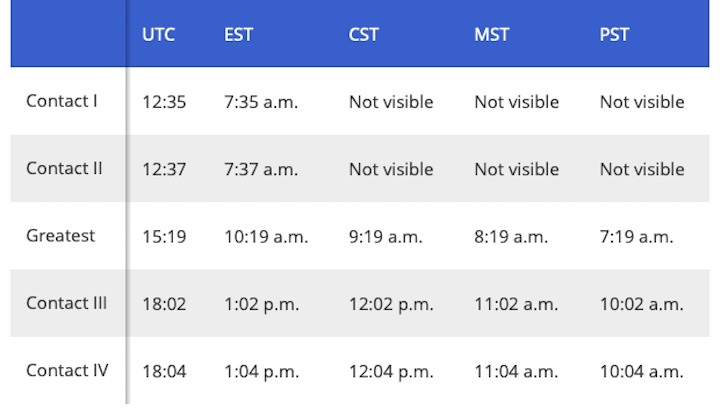

First contact is when the disk of Mercury first touches the eastern (left) edge of the sun. It takes about two minutes for the disk of Mercury to completely move onto the sun's disk (second contact). The greatest transit is when Mercury will appear nearest to the center of the sun. Third contact is when the forward edge of Mercury reaches the western (right) edge of the sun. Two minutes later, Mercury completely leaves the sun's disk (fourth contact).

Below is a timetable of the various stages of the transit in five time zones:

A word of caution to all prospective viewers: Mercury will appear as a black dot, only about 0.5% the diameter of the sun, so a telescope magnifying at least 50 power will be needed to see it. If there are any sunspots on the sun's disk, take note of how much darker the silhouette of Mercury appears to be compared to a sunspot. In addition, special precautions must be taken when viewing the dazzling solar disk. Be very careful to never look directly at the sun with a telescope. The visual requirements are identical to those for observing sunspots and partial solar eclipses — you need to use special solar filters to protect your eyes. It is far safer to project the sun's image through a telescope and onto a white card or screen.

If you are using a telescope with a large aperture, say 8 inches (20 centimeters) or more, you should place a circular mask in front of the objective lens or mirror to "stop down" the image, thereby reducing the amount of light and heat striking the lens or mirror.

Planetary peregrinations

Because Mercury's orbit is inclined 7 degrees to the plane of the orbit of Earth, most of the time when Mercury arrives at inferior conjunction — when it is between the Earth and the sun — it either will move above or below the sun and does not pass across the solar disk from our perspective on Earth. But at two points along Mercury's orbit, it will cross Earth's orbital plane (called a "node"). Earth crosses the line of nodes each year on May 8 or 9, and again six months later on Nov. 10 or 11. A transit can take place when an inferior conjunction of Mercury occurs within several days of these dates.

When a transit occurs in May, Mercury is near the aphelion point in its orbit — the point farthest from the sun and closest to the Earth. If Mercury passes centrally across the sun in May, the duration of the transit can last almost 8 hours.

When a transit occurs in November, as will be the case this month, Mercury will be near the perihelion point in its orbit — the point closest to the sun and farthest from the Earth, and where its apparent speed is faster. As such, a central transit in November has a duration of only 5.5 hours, which is pretty much what we will experience on Nov. 11. And the number of November transits outnumber the May transits by a factor of 2 to 1.

Mercury transits do not occur haphazardly. At 13-year and 33-year intervals, Mercury and the Earth return nearly simultaneously to the same points in their respective orbits, and hence a transit is often repeated after such a time interval.

So, related to the upcoming transit of Nov. 11, we can look back in time and find transits occurring 13 years ago, on Nov. 8, 2006 and 33 years ago, on Nov. 13, 1986.

Interestingly, the transits of May 9, 1970 and Nov. 10, 1973 both fell on a Saturday, while the transits of May 9, 2016 and Nov. 11, 2019 both fall on a Monday.

The next transit of Mercury will not occur until Nov. 13, 2032, but that will not be visible from North America. The next transit of Mercury visible from the United States will be on May 7, 2049.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 9.11.2019

.

Mercury putting on rare show Monday, parading across the sun

Mercury is putting on a rare show next week, parading across the sun

Mercury is putting on a rare celestial show next week, parading across the sun in view of most of the world.

The solar system's smallest, innermost planet will resemble a tiny black dot Monday as it passes directly between Earth and the sun. It begins at 7:35 a.m. EST.

The entire 5 ½-hour event will be visible, weather permitting, in the eastern U.S. and Canada, and all Central and South America. The rest of North America, Europe and Africa will catch part of the action. Asia and Australia will miss out.

Unlike its 2016 transit, Mercury will score a near bull's-eye this time, passing practically dead center in front of our star.

Mercury's next transit isn't until 2032, and North America won't get another viewing opportunity until 2049. Earthlings get treated to just 13 or 14 Mercury transits a century.

You'll need proper eye protection for Monday's spectacle: Telescopes or binoculars with solar filters are recommended. There's no harm in pulling out the eclipse glasses from the total solar eclipse across the U.S. two years ago, but it would take "exceptional vision" to spot minuscule Mercury, said NASA solar astrophysicist Alex Young.

Mercury is 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) in diameter, compared with the sun's 864,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers.)

During its 2012 transit of the sun, larger and closer Venus was barely detectable by Young with his solar-viewing glasses.

"That's really close to the limit of what you can see," he said earlier this week. "So Mercury's going to probably be too small."

Venus transits are much rarer. The next one isn't until 2117.

Mercury will cut a diagonal path left to right across the sun on Monday, entering at bottom left (around the 8 hour mark on a clock) and exiting top right (around the 2 hour mark).

Although the trek will appear slow, Mercury will zoom across the sun at roughly 150,000 mph (241,000 kph).

NASA will broadcast the transit as seen from the orbiting Solar Dynamics Observatory, with only a brief lag. Scientists will use the transit to fine-tune telescopes, especially those in space that cannot be adjusted by hand, according to Young.

It's this kind of transit that allows scientists to discover alien worlds. Periodic, fleeting dips of starlight indicate an orbiting planet.

"Transits are a visible demonstration of how the planets move around the sun, and everyone with access to the right equipment should take a look," Mike Cruise, president of the Royal Astronomical Society, said in a statement from England.

Quelle: abcNews

----

Update: 10.11.2019

,

Merkurtransit: "Mini-Sonnenfinsternis" ist wohl nur im Osten gut zu sehen

Am Montag wandert Merkur vor der Sonne entlang. Leider spielt das Wetter nicht mit – nur an wenigen Orten in Deutschland wird das Ereignis zu verfolgen sein.

Am Montag wird der Planet Merkur für einige Stunden vor der Sonnenscheibe entlangwandern. Allerdings dürfte die "Mini-Sonnenfinsternis" nur an wenigen Orten in Deutschland zu verfolgen sein: Das Wetter spielt nicht mit, vor allem im Westen der Republik verdecken Wolken den sogenannten Merkurtransit, wie ein Meteorologe des Deutschen Wetterdienstes (DWD) in Offenbach am Sonntag sagte. Der Vereinigung der Sternfreunde in Heppenheim zufolge beginnt das Schauspiel 13.35 Uhr.

Quelle: heise online