4.11.2019

Many scientists theorize stars, planets and the molecules that comprise them are only less than five percent of the mass-energy content of the universe. The rest is dark matter, invisible matter that cannot be directly detected but can be inferred. The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer - 02 (AMS-02) has been looking for evidence of this mysterious substance from the vantage point of the International Space Station since 2011.

Designed for a three-year mission of sifting through cosmic ray particles, AMS records the number of particles that pass through all its detectors (over 140 billion particles to date), the type of particle and characteristics such as mass, velocity, charge and their direction of travel. The goal is for scientists to track down their sources to help understand dark matter and the origins of the universe.

AMS has provided hundreds of researchers around the globe with data that can help piece together the puzzle of what the universe is made of and how it began.

"None of the AMS results were predicted," said Nobel Laureate and AMS principal investigator Samuel Ting in a presentation from 2018.

He said results so far have provided unique information to physicists and have included the potential detection of rare antimatter that may have traveled from the far reaches of the cosmos. While there have not been definite dark matter findings, AMS has collected a significant amount of data on cosmic rays, how the rays travel through space and what produces them.

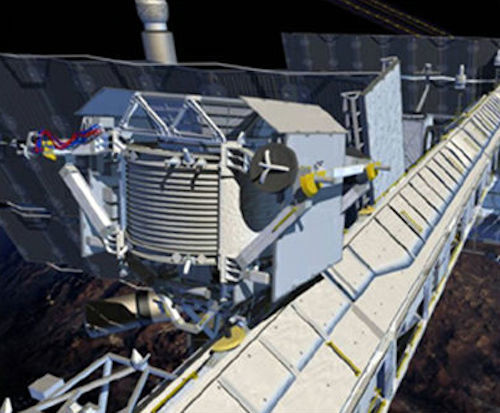

As with many items that are exposed to the harsh environment of space, it now needs an upgrade to continue its data collection. Over the course of the next few months, a complex series of spacewalks will go into action. The launch of a Northrop Grumman Cygnus spacecraft (NG-12) scheduled for launch on Nov. 2 will carry the final supplies needed for the spacewalks. Those supplies include the last tools needed to perform the upgrades.

At more than eight years on the station, AMS-02 has far outlived its expected three-year lifespan. AMS began showing signs of age in 2014. It has four redundant cooling pumps intended to keep the silicon tracker, one of several detectors on AMS, at a constant temperature while in space. With temperatures that fluctuate by hundreds of degrees while orbiting Earth, a functioning thermal control system is required to support the tracker, and data from the tracker is needed in combination with the data from the other instruments to support the AMS research.

While only one of these pumps is required to operate at a time, multiple pumps began to fail. In March 2014, one of the cooling pumps stopped working, and another was found to have degraded. In March 2017, researchers switched to the last fully functional pump to keep the science alive. The AMS team realized they would need to take action to keep the scientific instrument going. "A group of us started working on planning the spacewalks to extend the life of AMS and have been now for four years," said spacewalk task lead Brian Mader.

Fixing something that was never meant to be fixed

AMS was meant to live out its three-year life in space without maintenance and then wind down, having served its purpose. Since AMS was never planned to be serviced, there are no foot restraints nor handrails installed to help astronauts move around the areas to access the cooling system during a spacewalk.

It also was not designed with typical spacewalk tools in mind because, at over 300,000 data channels, it was considered too complex to service. "When you put somebody in a big suit with pressurized gloves with limited dexterity, it changes the game entirely. You have to design tools and procedures completely differently," Mader said.

In addition to the overall complexity of the instrument, astronauts have never before cut and reconnected fluid lines, like those that are part of the thermal control system, during a spacewalk. Scientists and engineers from around the world have been tackling these challenges over the past four years to prepare for the upcoming spacewalks. Now their procedures, tools and training are about to be put to the test.

The plan is to bypass the old thermal control system, attach a new one off the side of AMS and plug it into the existing system. "It sounds easy, especially if you're on the ground and have lots of different tools that you need, but it's not an area that was set up for spacewalking in any manner," said AMS spacewalk repair project manager Tara Jochim.

The work to prepare for the spacewalk has involved making, testing and launching more than 20 new tools to the space station. Many are specialized for specific steps of the spacewalk, such as removing the debris shield from AMS or working on the cooling lines. The tools include plumbing instruments to cut into the cooling lines, new screwdriver bits and devices to capture the fasteners the astronauts remove from AMS.

"The basic concept on removing the fasteners is actually something that they used on the Hubble Space Telescope spacewalks," said Flight Operations Directorate Spacewalk Lead John Mularski. "You use a tool to grab underneath the fastener before you fully remove it." The Hubble Space Telescope also required a series of spacewalks to extend the life of the telescope.

These tools have gone through years of iterations and tests here on Earth by scientists, engineers and astronauts. Considerable ingenuity was required to develop the perfect tools for the AMS spacewalks' very specific needs.

Repeated designing, prototyping, experimenting and validating was required to create all of the space ready tools. ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano and NASA astronaut Drew Morgan will perform all of the AMS repair spacewalks, and did many practice runs in the Neutral Buoyancy Lab (NBL) pool at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Several other members of the astronaut corps also helped perform other tests for tools to be used on the spacewalks. NASA astronaut Chris Cassidy and Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen assisted with tool development by carrying out trials in both the NBL and the Active Response Gravity Offload System (ARGOS), a facility that simulates reduced gravity environments out of the water.

More to offer

Ting and the researchers using AMS data are hopeful that these spacewalks will enable many more years of data collection for this specialized instrument. "A lot of experiments can measure these cosmic ray particles at low energies. AMS takes it to a much higher energy level and to an unprecedented accuracy," said AMS Project Manager Ken Bollweg. "In order to continue to improve the accuracy, they have to take data for a longer time."

This extension of AMS's life may also allow scientists to get a more complete picture of radiation in space by collecting data over a complete solar cycle-a period of about 11 years during which the Sun's magnetic field changes, exposing the solar system to different levels of radiation. Collecting information over that entire time could provide more information about the potential radiation exposure for astronauts headed to Mars.

In addition to revitalizing an important piece of scientific equipment, the process of creating the tools and procedures for these spacewalks is preparing teams for the types of spacewalks that may be required on Moon and Mars missions. "These are the kind of skills that are going to feed into going to a planetary surface," Jochim said.

"Cutting stainless steel tubing and then connecting new tubes on a thermal system during a spacewalk with the user-friendly mechanisms we have developed, all the while keeping it safe for the crew member, are the types of activities that will help create our processes for tomorrow's spacewalkers."

AMS is a joint effort between NASA and the Department of Energy's Office of Science and is led by Principal Investigator Samuel Ting, a Nobel laureate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The AMS team includes some 600 physicists from 56 institutions in 16 countries from Europe, North America and Asia. The contributions from the various participants were integrated when the AMS was built at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) outside of Geneva, Switzerland.

Quelle: SD