23.02.2019

The Martian Mole will hopefully unveil secrets of a Martian past, with lessons that may teach us about Earth.

Heat shapes Earth. Our blue marble, the only planet known to support life, gets heat from the sun, of course, but also from its molten core. That internal furnace provides Earth's magnetic field and its geography on the whole—everything from foothills to volcanoes to earthquakes owe their genesis to heat at a tectonic level. The inner workings of Earth are crucial to understanding the planet and how life formed here.

That's why NASA is sending a robotic hammer to Mars. It has the potential to dig 16 feet into the Martian regolith and then can take the planet's temperature, exploring deeper than humanity has ever gone on an alien world . It's called the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, often referred to by engineers as a "mole."

"In science, you always want to compare to something else," says Dr. Tilmon Spohn, director of the Institute of Planetary Research of the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and principal investigator for the HP3 instrument, which is currently on Mars. "For practical reasons, you want to look at planets that are similar. That's why Mars is better than Jupiter."

In Cosmos, Carl Sagan wrote that "Mars has become a kind of mythic arena onto which we have projected our Earthly hopes and fears." And that was back in 1980. From Bradbury to Burroughs, the planet has played an outsize role in modern mythology. Now, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk says there is a “70 percent chance” that he will move to the Red Planet.

Discussions of humanity as an interplanetary species have grown more common, but as Sagan reminded readers in Cosmos: "Our psychological predispositions pro or con must not mislead us. All that matters is the evidence, and the evidence is not yet in." NASA's InSight probe, with its self-hammering HP3 instrument, is getting the evidence.

There have been many explorations of the Martian surface at this point. Opportunity just finished its historic 14-year trek across the planet, running over a marathon and definitively discovering that Mars once held water. Now, InSight is running tests that will hopefully capture a glimpse of the history of the planet.

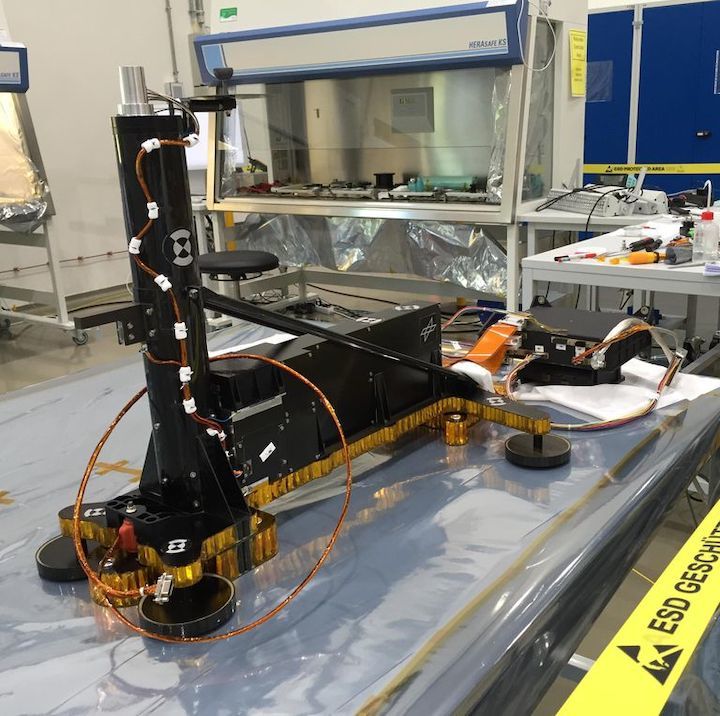

On a technical level, HP3 is a marvel. NASA describes it as looking "a bit like an automobile jack" with a vertical metal tube.

"That thing weighs less than a pair of shoes, uses less power than a Wi-Fi router and has to dig at least ten feet [three meters] on another planet," says Troy Hudson, a scientist and engineer who helped design HP. "It took so much work to get a version that could make tens of thousands of hammer strokes without tearing itself apart; some early versions failed before making it to 16 feet [five meters], but the version we sent to Mars has proved its robustness time and again."

The early tests were rough. "Every time the hammer hits, inside the tip, it creates ten and 20 thousand g's of acceleration because it's a very fast, very high-impulse event," Hudson explained to Popular Mechanics. "Even though the mole is not that big—if you have a loop of wire, it will vibrate. So, over many cycles, that stress will cause the wire to break."

First proposed in 1997, the mole had its design changed again and again. "Early prototypes built in the lab used petroleum-based greases," Hudson explains. "But those aren't good under low temperatures, and they can get gummed up if there's any dust leak—there shouldn't be, but we wanted to prevent any eventuality—so we had to switch to dry lubrication. Surface coatings, which are much harder to apply. More robust, but difficult."

Even with all that prep work, there are no guarantees for the mole. One advantage a rover has over a mole: Scientists can see where it is going. One of the most crucial elements of any planetary exploration is the landing site, which often shapes the nature of the mission. NASA's recent selection of the Jezero Crater for its 2020 Mars rover, for example, shows a keen interest in understanding the planet's ability to harbor life. The selection was made after years of studying Jezero and determining its historic status.

The mole landing team has no such luxuries. While the HP3 is powerful enough to drive through rock, it's not on a mission of construction or conquest. It's on a mission of science, which means careful analysis of every data point.

Here's how an ideal mole mission will go. "There's a penetration cycle that takes about four days," Hudson explains. The hammering will go down 50 centimeters. There will be a time limit on this drilling of four hours, but the NASA team hopes it will take less, possibly even just half an hour.

"Then we sit quietly for three days and let the heat from that hammering dissipate," Hudson says. After that, the hammer warms up again over another 24 hours. That heat pulse allows NASA to measure thermal conductivity. "The mole only heats up around ten degrees" during that warming period, but the team needs "that long slow rise to get a good thermoconductivity measurement."

That's what will happen, most likely next week, if everything below the surface is regolith. Drilling into solid rock could create a cacophony that would risk drowning out the mole's scientific instruments. If the mole encounters a rock, what could be a quick mission might be dragged out to an entire year.

NASA has taken the precautions it can. It's found a spot with very few rocks on the surface, Hudson explains, which hopefully suggests that there are no rocks below the surface.

While he's nervous, Hudson tells Popular Mechanics that "all the worrying that would have made any difference happened years ago. At this point, we're going to explore. We're going to learn something about the subsurface of Mars. Whether that something is, 'It's really, really tough!' or, 'It's great, we can go right through it,' either one would be useful. But we'd really rather have the second one."