22.03.2018

Dutch amateur astronomer Eise Eisinga might have left school at 12 years old, but he built an inch-perfect model of the solar system in his living room.

There was a beat of silence as the room’s atmosphere shifted from inward reflection to jittery disbelief. “How is that even possible?” said one visitor, waving a pointed finger at the living-room ceiling. “Is it still accurate?” asked another. “Why have I never heard of this before?” came the outburst from her companion. Craning my neck, I too could hardly believe it.

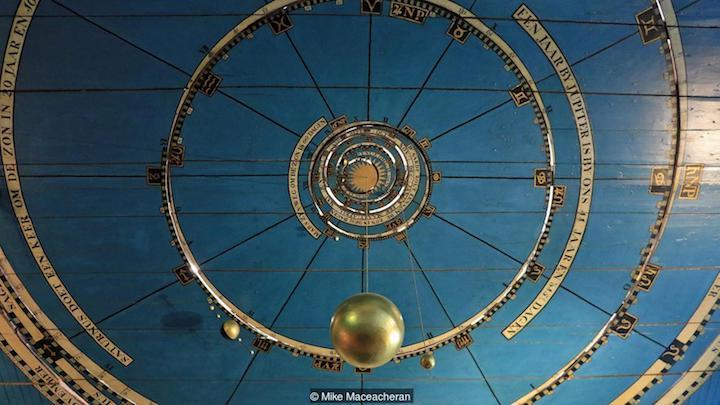

On the timber roof above our heads was a scale model of the universe, painted in sparkling gold and shimmering royal blue. There was the Earth, a golden orb dangling by a near-invisible, hand-wound wire. Next to it, the sun, presented as a flaming star, glinting like a Christmas bauble. Then Mercury, Venus, Mars, and their moons in succession, hung from a series of elliptical curves sawn into the ceiling. All were gilded on one side to represent the sun’s illumination, while beyond, on the outer rim, were the most-outlying of the planets, Jupiter and Saturn. Lunar dials, used to derive the position of the zodiac, completed the equation.

The Royal Eise Eisinga Planetarium is the world’s oldest working planetarium (Credit: The Royal Eise Eisinga Planetarium)

-

The medieval science behind the Royal Eise Eisinga Planetarium is staggering, no matter how one views it. Tucked away in a gabled canal-side house in the tiny town of Franeker, in the Netherlands’ north-west Friesland province, it is the world’s oldest working planetarium, or orrery. The origins of Western astronomy date back to ancient Mesopotamia along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. But it took a Frisian amateur – Eise Eisinga – to trap the universe in his living room. And the science behind it is still precise today.

How accurate? Look up, and every planet, star, sun and moon moves exactly as they do in reality, albeit reduced in scale by a factor of one trillion, meaning 1mm on the ceiling represents one million km. Jupiter takes 12 years to orbit the sun. Saturn, 29 years. Uranus, Neptune and Pluto are missing, of course, because they hadn’t been discovered when Eisinga hammered in the final nail in 1781. Even so, it is astonishing: a Baroque theatre for stargazers, crowning the living room of a modest wool comber who lived shortly after the Dutch Golden Age. All told, an unfathomable undertaking considering Eisinga quit school aged 12.

Every planet, star, sun and moon moves exactly as they do in reality

The Royal Eise Eisinga Planetarium, today an astronomy museum and centre for space exploration, has been drawing people from around the world ever since it opened in 1781. It’s listed as a Rijksmonument, a national heritage site in the Netherlands, and stargazers, layman astronomers and mission astronauts have visited, hoping they, like Eisinga, can be inspired.

One such individual is Adrie Warmenhoven, the museum’s director, who never fails to be astonished by its accuracy. At certain times of year, Warmenhoven explained, he can see the sunrise above IJsselmeer bay when he crosses the Afsluitdijk causeway on his way to work. “When I step into the planetarium later, I can see the same time of the morning on the dial,” he said excitedly when I visited on a clear February afternoon. “A few years ago, Venus transited the sun, a rare astronomical phenomenon, yet even it was visible inside the planetarium. Incredible, right?”

Eisinga’s solar system is reduced by a factor of one trillion, with every 1mm representing one million km (Credit: Mike Maceacheran)

-

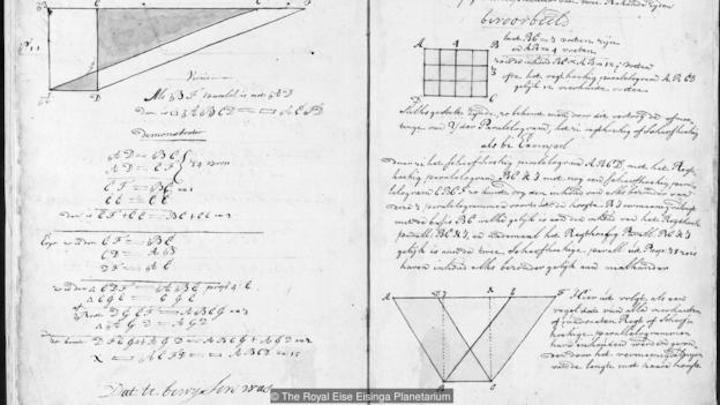

While Eisinga’s story is well known within his home province of Friesland, it’s a tale that would be lost to the rest of us without the planetarium – and the well-thumbed handbook he left behind. Filled with sketches and drawings, it explains in minute detail how to maintain the orrery, long after its inventor was gone.

“The planetarium is very exact, but not perfect,” Warmenhoven said, explaining the clockwork-like mechanism. “The pendulum, for instance, is made of a single type of metal so it’s influenced by temperature fluctuations. Then there are the planet wheels themselves, which create problems because of their size. So according to Eisinga’s manual, we have to adjust them every 10 to 12 years.”

It was on 8 May 1774 that Eisinga first put his self-taught knowledge to good use. Panic had erupted among the villagers of Franeker when a doomsday scenario was presented to them by Eelco Alta, a Frisian clergyman and theologian. An upcoming planetary alignment, they were told, meant the Earth would burn to ashes in the sun.

It must have felt – if only just for a moment – that time had stopped

Eisinga, little more than a hobbyist, wanted to show them the truth. His aim was not to make a mockery of the church, but to predict future planetary movements and show the townsfolk how wrong they were.

“Eisinga knew every planet had its own orbit around the sun,” tour guide Mascha Noordermeer told me as she traced complex circles across the ceiling as Eisinga once did. “That [the project] would take seven years to complete, and nearly bankrupt him, was just an afterthought.”

For nearly a decade, Eisinga worked on the project in his spare time, the planetarium slowly evolving above the box-sized kitchen and cupboard bed where he slept with his wife and son. Then, as dawn broke one morning in 1781, everything looked just right. He had entered that liminal space, where he could touch the stars from his living room. It must have felt – if only just for a moment – that time had stopped.

The mathematical ingenuity required for the planetarium’s design takes time to process (Credit: Mike Maceacheran)

-

Here’s a tip should you decide to visit: don’t rush. As well as displays of Georgian telescopes, 18th-Century octants and a tellurium (an educational model of the Earth, moon and sun, the latter represented by a flickering candle), the mathematical ingenuity required for the planetarium’s design takes time to process.

Another discovery comes in the attic. Hard-wired by a complex system of clockwork wooden hoops and disks, tightly bound by cables bathed in dusty gloom, Eisinga’s model of the solar system is held together by more than 10,000 homemade nails, which serve as gear teeth. So impressed was William I, Prince of Orange and the first King of the Netherlands, when he climbed into this same pitched loft 200 years ago, he decided to buy it outright. For the vast sum of 10,000 guilders – a fortune in the early 19th Century – Eisinga’s house became a royal planetarium for the State, the only stipulation being that its inventor should live in it for free to provide explanation.

I emerged blinking back onto Franeker’s streets. As ivy-draped houses caught the last of the day’s light, a slew of stars began to appear. Cyclists pedalled along cobbled canal ways and in front of the medieval Martinus Church a newly installed basin fountain sat in darkness. Built in honour of another great Dutch astronomer, it is dedicated to Jan Hendrik Oort, born in Franeker in 1900, whose assumption that the Milky Way moves around our solar system – and not the sun – was proved correct. Only then did I realise that for such a small town, Franeker has made the universe so much larger, so much brighter, for everyone.

Eisinga died aged 84, buried in nearby Dronrijp, 7km away, where he first grew up. Today a bronze statue, dedicated to this extraordinary wool comber, looks enduringly to the skies in the shadow of the house in which he was born. As tributes go, it’s one he’d surely be proud of.

Quelle: BBC travel