Scientists and science fiction writers alike have long wondered about what forms alien life might take on other worlds. Now researchers have strengthened the case that, at least on Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, some alien life might closely resemble a specific type of microbe found deep in our own planet’s seas. Such alien organisms may even be living there now, and if so, could conceivably become the first discovered beyond Earth.

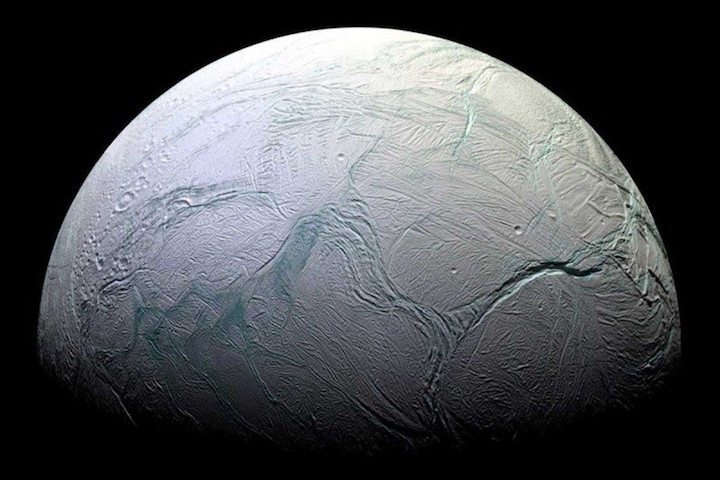

“We had speculated about the possibility of life outside the ‘habitable zone’ in our solar system,” says Simon Rittmann, a biochemist at the University of Vienna, referring to the limited orbital region where starlight-warmed planets can host liquid water on their surfaces. “Now we’ve found in our modeling that some of the methane produced on Enceladus could be of biological origin.” Enceladus, of course, lies far outside the habitable zone, but nonetheless boasts a deep liquid ocean beneath its icy crust.

Rittmann led a team performing a series of experiments and modeling to determine if any three methane-producing microbes could grow in the crushing depths of the ocean’s cold, briny and alkaline waters. They argue one of these so-called “methanogen” species could indeed live there, encouraging more detailed research and missions to find out for sure. They published their findings in the February 27 Nature Communications.

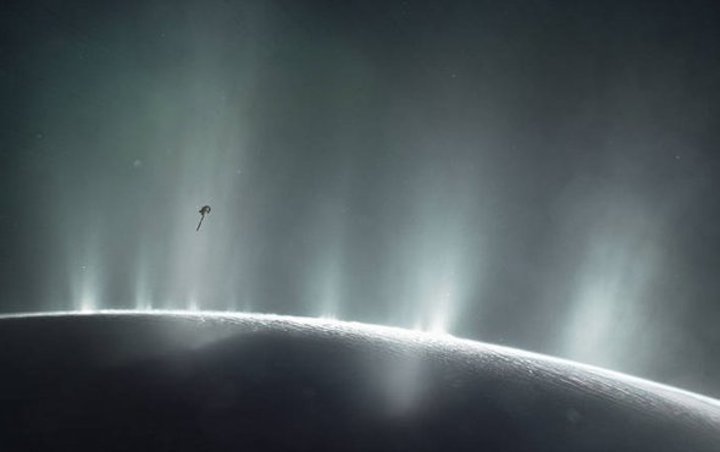

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft previously revealed Enceladus’s ocean by monitoring geyserlike plumes spewing from the moon’s south pole. Within the plumes it found chemical signatures of a saltwater ocean sandwiched between the moon’s icy crust and rocky core as well as tentative evidence of hydrothermal vents on that alien seafloor. It also caught whiffs of hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane, along with signs of organic compounds such as methanol. In Earth’s oceans such a cocktail of gases would suggest the presence of hydrogen-eating, methane-belching microbes—but extrapolating that conclusion to the very different geology and chemistry of Enceladus required a rather unscientific leap of faith. More research was—and is—needed.

“Hydrogen and carbon dioxide are the only chemical sources of energy that we know are there, and who consumes that?: methanogens. This paper takes that to the next level and demonstrated it experimentally,” says Chris McKay, a planetary scientist at NASA Ames Research Center. McKay is also the lead investigator for the Enceladus Life Signatures and Habitability project, a proposed NASA space mission.

Using various mixtures of gases held at a range of temperatures and pressures in enclosed chambers called “bioreactors,” Rittmann and his co-authors cultivated three microorganisms belonging to the oldest branch of Earth’s tree of life, known as Archaea. In particular, they focused on Archaean microbes that are also methanogens, which are able to live without oxygen and produce methane from that anaerobic metabolism. The team examined the simplest types of microbes, which could be the primary producers of methane at the base of a possibly more complex ecological food chain within the moon.

They tried to simulate the conditions that could exist within and around Enceladus’s hydrothermal vents, which are thought to resemble those found at a few deep-sea sites on Earth, often near volcanically active mid-oceanic ridges. According to their tests, only one candidate, the deep-sea microbe Methanothermococcus okinawensis, could grow there—even in the presence of compounds such as ammonia and carbon monoxide, which hinder the growth of other similar organisms.

Scientists do not really know the precise conditions on Enceladus yet, of course. And in any case it is possible any life there, if it exists, is nothing like any DNA-based organism on our planet, rendering our Earth-based extrapolations moot. What’s more, these findings only show microbial life might exist in one particular subset of possible environments within the moon’s dark ocean. Rittmann’s argument is an indirect one that could explain the methane emanating from the moon, but the evidence remains muddled and inconclusive—on Earth, certain geochemical reactions between hot water and rocks beneath the seafloor can also generate significant amounts of methane without the presence of microbes.

The tantalizing possibility of life on another world orbiting our sun, even if it is in the outer solar system and hidden beneath a kilometers-thick crust of rock-hard ice, has sparked more interest from the world’s space agencies. Nascent missions to explore Enceladus further as well as other icy ocean worlds with similar conditions, especially Jupiter’s moon Europa, are already in various stages of development at NASA and the European Space Agency.

One possibility would be to send a spacecraft with a suite of powerful new instruments to orbit or fly by Enceladus, to sniff out clearer signs of habitability and even life in the plumes jetting from the moon. That approach is endorsed by Hunter Waite, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio who helmed Cassini’s earlier analysis of the moon’s geysers. But to answer the question definitively, he says, one would want to deploy some kind of robotically controlled submarine in that ocean—while making sure the probe is free of any hitchhiking microbes imported from Earth.

We’re looking at 30 to 40 years for such a mission, Waite says. “But if you went and confirmed these things and saw signs of life, I think people would want to go back.”