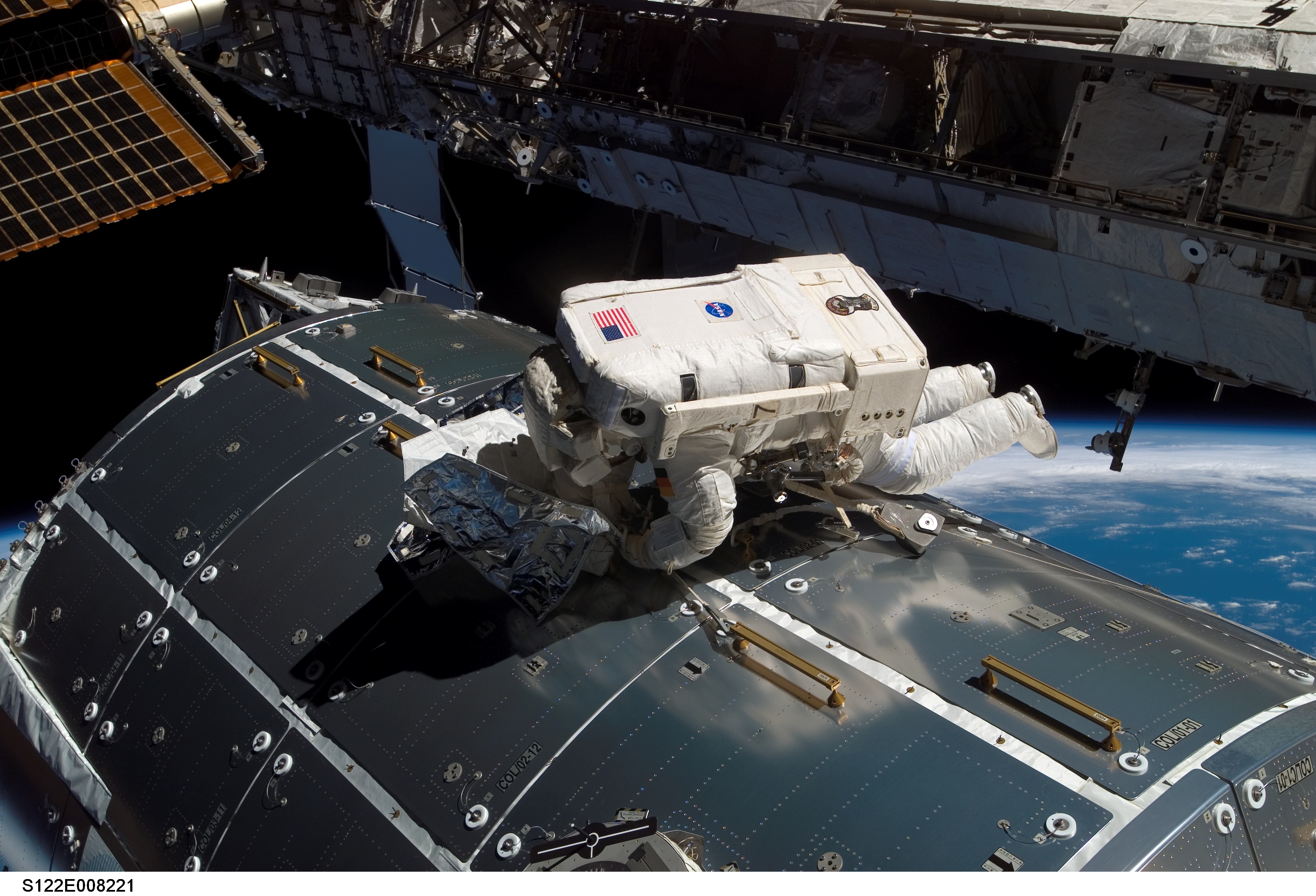

Spacewalker Rex Walheim works to outfit the exterior of Europe’s Columbus lab during STS-122, which launched ten years ago, this week. Photo Credit: NASA, via Joachim Becker/SpaceFacts.de

Ten years ago, this month, Space Shuttle Atlantis sprang from historic Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, to kickstart the final phase of International Space Station (ISS) construction. A decade since the first elements of the football-field-sized outpost had been placed into orbit, the core structure was in place, ready to accept the pressurized modules of the international partners. First up was Columbus, the largest single contribution of the European Space Agency (ESA).

More than 22.5 feet (6.8 meters) in length and 15 feet (4.5 meters) in diameter, it would be permanently attached to the starboard port of the station’s Harmony node and, over its first decade of operational life, saw no fewer than 13 European astronauts from France, Germany, Belgium, Sweden, Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark and the United Kingdom float through its hatch, support a broad range of scientific research and display their national flags in its roomy interior. In its ten years, Columbus has supported more than 1,700 discrete experiments and an estimated 800 terabytes of data has passed through its Data Management System (DMS).

Columbus had evolved from an early ESA program to develop an autonomous manned space station, tended by the French-built Hermes mini-shuttle. Budget cuts eventually killed off both Hermes and Columbus’ man-tended free-flyer and polar platform components, leaving only its Attached Pressurized Module (APM). This morphed into the lab which today resides aboard the ISS. Its structure was closely modeled upon the Italian-built Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) and Columbus’ core was delivered for integration to Bremen, Germany. In early 2003, the development of the Columbus Control Centre got underway at Oberpfaffenhofen, near Munich, Germany, with an expectation that the lab itself would launch in October 2004. That was indefinitely postponed, following the loss of Columbia, but following the resumption of shuttle missions the campaign to launch Columbus entered high gear.

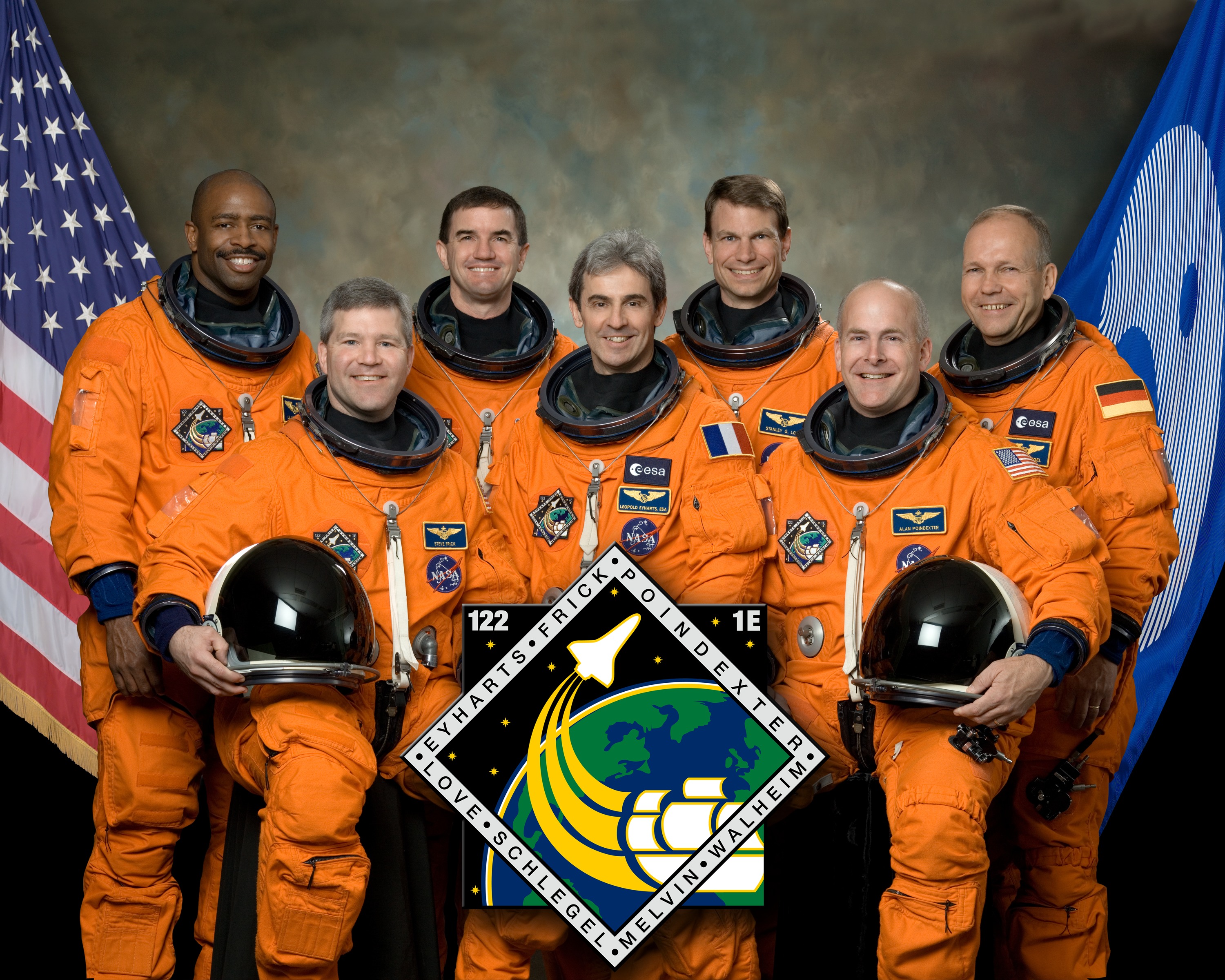

By April 2006, Columbus’ final integration was completed in Europe and the module was shipped to KSC in May to be prepared for launch. In July, the six-man STS-122 crew—Commander Steve Frick, Pilot Alan “Dex” Poindexter and Mission Specialists Leland Melvin, Rex Walheim, Stan Love and Germany’s Hans Schlegel—were formally assigned to the task of installing and activating Columbus. They also picked up French astronaut Léopold Eyharts, who would remain aboard the ISS for several weeks. Their launch was targeted for September 2007, but eventually found themselves rescheduled for 6 December.

With only Frick, Walheim and Schlegel having flown the shuttle before, it would be the first space voyage of Poindexter, Melvin and Love. Their training, said Melvin, was akin to telepathy after a while. “There may be times when we have to communicate just like a wide receiver and a quarterback,” he said. “It’s a non-verbal thing. He [Poindexter] can start making a motion toward a switch and I know that’s the right switch. I can just tap him or I can nod and he can look in the mirror. We have a lot of communication like that.”

However, the gremlins were not far away from STS-122. Launch moved to 9 December, following false readings from two of the four Engine Cutoff (ECO) sensors inside the liquid hydrogen segment of the External Tank. The sensors were a critical component, protecting Atlantis’ cluster of three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) by triggering their shutdown if the fuel level ran unexpectedly low. However, early on the 9th, a false reading on another sensor prompted a scrub until no earlier than 2 January 2008. This date was itself moved to the 10th, in order to allow ground processing teams the time to spend with their families over the Christmas period, and again until the first half of February. At length, a revised launch on 7 February was confirmed by NASA.

The STS-122 crew also included French astronaut Leopold Eyharts, who remained aboard the International Space Station (ISS) as part of Expedition 16, to continue the outfitting of Columbus. From left to right are Leland Melvin, Steve Frick, Rex Walheim, Leopold Eyharts, Stan Love, Alan “Dex” Poindexter and Hans Schlegel. Photo Credit: NASA

With a whoop of joy, the STS-122 crew—joined by Eyharts—left Earth at 2:45 p.m. EST on 7 February 2008, carrying the space station’s second lab into orbit on the seventh anniversary of the launch of its first. After reaching orbit, the crew dove directly into their two-day rendezvous regime to reach the ISS. For Schlegel, who had last flown in early 1993, it was remarkable how quickly he adapted to microgravity. “I realized, hey, your body knows this,” he said later. “It was really a great feeling to be back.” For the rookies, the excitement was equally acute. Melvin remembered that there didn’t seem enough shades of blue to describe the color of the Caribbean Sea and Schlegel added that the entire region was “just breathtaking”.

In keeping with procedures set in place after the Columbia disaster, they spent time early in their mission inspecting the shuttle’s heat shield with the sensor-tipped Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) at the end of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm. Additionally, they set up the centerline camera in the Orbiter Docking System (ODS) in Atlantis’ payload bay and Walheim, Schlegel and Love checked out the space suits to be worn during the three planned sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA).

Expedition 16 Commander Peggy Whitson assists spacewalkers Rex Walheim (right) and Hans Schlegel with their suits. Photo Credit: NASA

Early on 9 February—Whitson’s 48th birthday—the shuttle drew closer to its quarry and Frick executed a 360-degree Rendezvous Pitch Maneuver (RPM), backflipping Atlantis to enable the Expedition 16 crew to acquire high-resolution imagery of the heat shield. Of specific interest was a slightly protruding thermal blanket over the shuttle’s starboard Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pod. Meanwhile, the RPM got underway shortly after 11 a.m. EST, at a distance of 600 feet (180 meters), after which Frick guided his ship ahead of the ISS and performed a smooth 12:17 p.m. docking at Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2, at the forward end of the Harmony node. The only problem of note was a glitch with one of the station’s computers, which hiccuped during the rendezvous. After pressurization and leak checks, the shuttle crew was welcomed aboard the station by the Expedition 16 trio of Whitson, NASA’s Dan Tani and Russian cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko.

Almost immediately, however, a delay reared its head. The planned installation of Columbus on 10 February and the first EVA was pushed back by 24 hours, due to a crew medical issue pertaining to Schlegel. It was decided to add an extra day onto STS-122—increasing the flight to 12 days—and in doing so permit additional time to outfit the 2,648 cubic feet (75 cubic meters) inside Columbus. What was not delayed, however, was the rotation of two ISS crewmen, with NASA astronaut Dan Tani—who launched to the station in October 2007—relinquishing his duties to Eyharts, who would put Columbus through its paces during its early weeks in orbit. By the evening of the 9th, Eyharts was officially a member of Expedition 16, alongside Whitson and Malenchenko, whilst Tani formally joined the STS-122 crew for the end of his mission.

In the meantime, a focused inspection of the starboard OMS pod yielded a clean bill of health for Atlantis’ re-entry and the two crews pressed into their efforts to install Columbus. Stan Love was reassigned to perform the first and third EVAs alongside Walheim, with Schlegel expected to perform the second. The two spacewalkers camped overnight in the station’s Quest airlock, before venturing outside to install the Power and Data Grapple Fixture (PDGF) onto Columbus. Their first view as the hatch opened was the Swiss Alps, drifting beneath them, which Walheim later described as “a spectacular sight”. Originally, before the loss of STS-107, the PDGF installation should not have been necessary. But in the aftermath of Columbia, the 50-foot (15-meter) sensor-tipped boom was added to each flight for heat shield inspections and this left precious little room in the payload bay for Columbus and the PDGF. As a result, the grapple fixture would be installed by spacewalkers. “That has to go exactly as planned,” said STS-122 Lead Flight Director Mike Sarafin. “Otherwise we can’t get Columbus out of the payload bay.” Fortunately, all went smoothly.

With the PDGF in place, Melvin grappled the lab with the RMS and hoisted it out of the shuttle’s payload bay and into position at the starboard side of Harmony. “My video game skills helped me out a lot on this,” he admitted later, with a chuckle. “It was a beautiful, beautiful moment.” Yet in his memoir, Chasing Space, Melvin was acutely aware of the seriousness of his work and the heavy burden of responsibility imposed upon him by ESA in getting their lab attached safely. In September 2006, he was introduced to ESA leaders and received a standing ovation. “I felt pressure knowing that all of them had been waiting so long for this moment,” Melvin wrote, “and I was their guy to do the job.” With only half-humor, one German official turned to him and said quietly: “Don’t screw it up!”

Hans Schlegel was only the second German, after Thomas Reiter, to perform a spacewalk. He also remains the oldest European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut to make an EVA. Photo Credit: NASA

After a 42-minute journey, Columbus officially became part of the ISS and motorized bolts locked the two modules together. Walheim and Love returned inside the airlock after seven hours and 58 minutes, having also prepared for a subsequent task of removing a degraded Nitrogen Tank Assembly (NTA) from the station’s P-1 truss.

With Columbus in place, 57 percent of the station was in place, in terms of mass. At 9:08 a.m. EST the next morning, 12 February, Eyharts and Schlegel opened the hatches and entered Columbus for the first time. “This is a great moment,” said Eyharts, “and Hans and I are very proud to be here and to ingress for the first time the Columbus module.” The Columbus Control Centre in Oberpfaffenhofen formally assumed command of the module’s operations and, despite a temporary hiccup during the integration of the cooling system, all proceeded nominally.

A second EVA on 13 February saw Walheim and Schlegel spend six hours and 45 minutes removing the degraded NTA, which serves to pressurize the station’s ammonia cooling system, and replace it with a fresh unit. With this task satisfactorily completed, they conducted some minor repairs to the debris shield on the U.S. Destiny lab. The third and final spacewalk on the 15th involved the installation of two external payloads onto Columbus: namely, SOLAR and the European Technology Exposure Facility (EuTEF). This time, Walheim and Love spent seven hours and 25 minutes in the vacuum of space. In addition to the SOLAR and EuTEF installations, they removed a degraded Control Moment Gyroscope (CMG) for return to Earth and inspected damage to an airlock handrail. All told, STS-122 logged more than 22 hours of EVA time.

Over the next few days, the combined crews reboosted the ISS orbit by about 1.4 miles (2.2 km)—the first time that this had been done with shuttle thrusters since 2002—and continued to outfit Columbus itself. All told, the module afforded room for ten new experiment racks and the STS-122 crew also delivered 95 pounds (43 kg) of oxygen to Quest’s tanks and 1,400 pounds (635 kg) of water. There was also time to share joint meals with the Expedition 16 crew. One evening, Whitson invited the shuttle crew over the Zvezda service module for dinner. “There we were,” wrote Melvin, “French, German, Russian, Asian-American, African-American, listening to Sade’s silky vocals and having a meal in space. Out the window, we could see Afghanistan, Iraq and other troubled spots.” To him, it seemed astonishing that such strife-torn places appeared so peaceful from space.

Frick undocked Atlantis from the station in the early hours of 18 February, allowing Poindexter to perform a flyaround inspection and eventual departure. “It flies better than the simulator,” Poindexter said later, describing the impulse of the thrusters as “like cannons going off”.

With Eyharts remaining aboard the station, alongside Whitson and Malenchenko, Dan Tani bade farewell to his orbital home of the past four months. Backdropped by near-perfect weather conditions, Atlantis swept to a smooth touchdown on Runway 15 of the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Cape at 9:07 a.m. EST, wrapping up a mission of almost 13 days and 202 orbits of Earth. But for Tani, it had been even longer. He had spent nearly 120 days in space, performed five EVAs and had sadly received the news of his mother’s death in a road accident. His physical health after landing astonished Steve Frick. “Dan was doing great,” Frick remarked. “He looked better than I did. Really!”

Quelle: AS