The infrared cameras (IR1 and IR2) need no sunlight to see Venus. They observe in wavelengths at which the hot atmosphere radiates thermally. IR2 has two channels, 1.74 and 2.26 microns, which detect heat at a still-high 48 to 55 km above the surface. Seen at these wavelengths, dark features are higher-altitude clouds that block Akatsuki's view of the glow of the warm atmosphere lower down. Researchers suspect that the motions of clouds at these mid-level altitudes are more sensitive to topography lying far below.

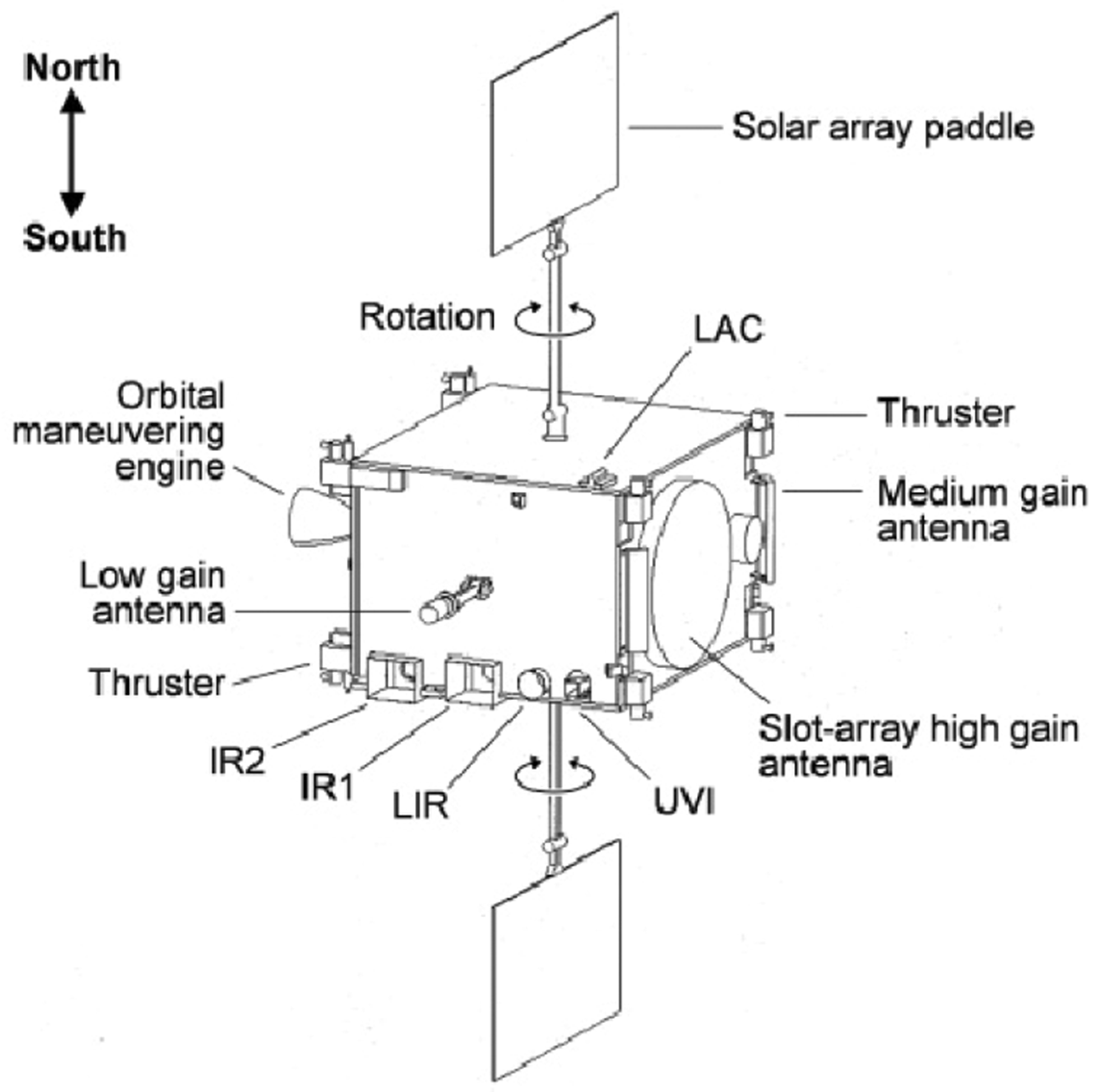

Unfortunately, the two infrared cameras (IR1 and IR2) suffered an electrical fault in December 2016. But the long-wave infrared (LIR) imager, Lyman-alpha camera (LAC), and ultraviolet imager (UVI) all still function.

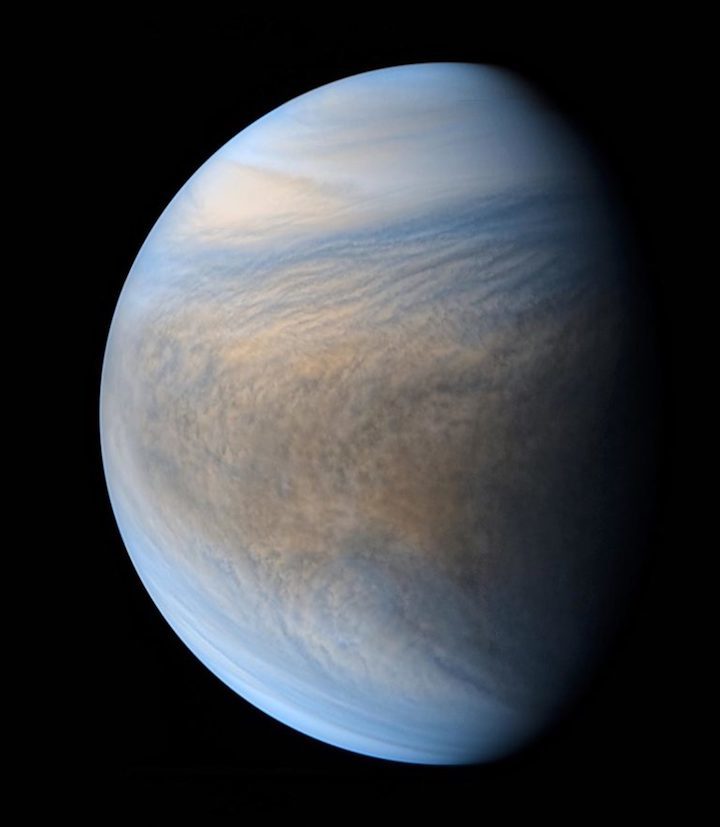

Late in 2017, the mission made its first release of science data to the Akatsuki data archive. That's when Damia Bouic, an amateur image processor in France, delved into the raw image files and surfaced with the data that she used to make these remarkable views of Venus as seen through the ultraviolet and infrared cameras.

View more of Bouic's amazing Akatsuki reconstructions here (and visit her website here). Even more Akatsuki observations are readily available to the public, waiting to be explored and enjoyed.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope

----

Update: 11.01.2019

.

Giant pattern discovered in the clouds of planet Venus

A Japanese research group has identified a giant streak structure among the clouds covering planet Venus based on observation from the spacecraft Akatsuki. The team also revealed the origins of this structure using large-scale climate simulations. The group was led by Project Assistant Professor Hiroki Kashimura (Kobe University, Graduate School of Science) and these findings were published on January 9 in Nature Communications.

Venus is often called Earth’s twin because of their similar size and gravity, but the climate on Venus is very different. Venus rotates in the opposite direction to Earth, and a lot more slowly (about one rotation for 243 Earth days). Meanwhile, about 60 km above Venus’ surface a speedy east wind circles the planet in about 4 Earth days (at 360 km/h), a phenomenon known as atmospheric superrotation.

The sky of Venus is fully covered by thick clouds of sulfuric acid that are located at a height of 45-70 km, making it hard to observe the planet’s surface from Earth-based telescopes and orbiters circling Venus. Surface temperatures reach a scorching 460 degrees Celsius, a harsh environment for any observations by entry probes. Due to these conditions, there are still many unknowns regarding Venus’ atmospheric phenomena.

To solve the puzzle of Venus’ atmosphere, the Japanese spacecraft Akatsuki began its orbit of Venus in December 2015. One of the observational instruments of Akatsuki is an infrared camera “IR2” that measures wavelengths of 2 μm (0.002 mm). This camera can capture detailed cloud morphology of the lower cloud levels, about 50 km from the surface. Optical and ultraviolet rays are blocked by the upper cloud layers, but thanks to infrared technology, dynamic structures of the lower clouds are gradually being revealed.

Before the Akatsuki mission began, the research team developed a program called AFES-Venus for calculating simulations of Venus’ atmosphere. On Earth, atmospheric phenomena on every scale are researched and predicted using numerical simulations, from the daily weather forecast and typhoon reports to anticipated climate change arising from global warming. For Venus, the difficulty of observation makes numerical simulations even more important, but this same issue also makes it hard to confirm the accuracy of the simulations.

AFES-Venus had already succeeded in reproducing superrotational winds and polar temperature structures of the Venus atmosphere. Using the Earth Simulator, a supercomputer system provided by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), the research team created numerical simulations at a high spatial resolution. However, because of the low quality of observational data before Akatsuki, it was hard to prove whether these simulations were accurate reconstructions.

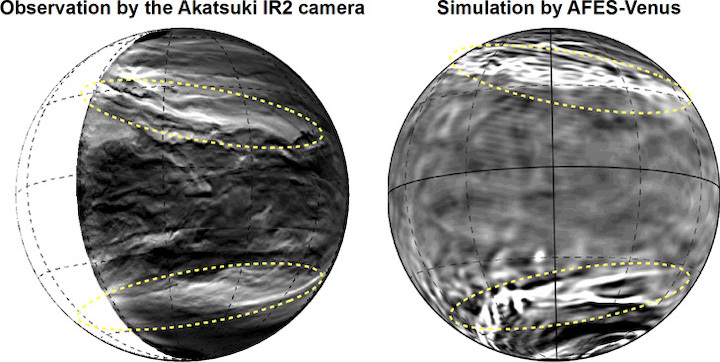

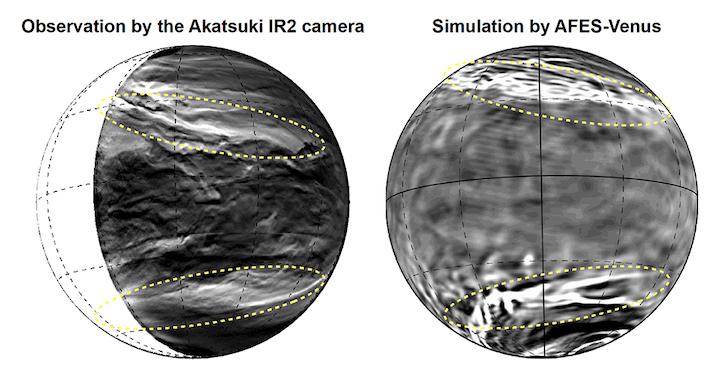

This study compared detailed observational data of the lower cloud levels of Venus taken by Akatsuki’s IR2 camera with the high-resolution simulations from the AFES-Venus program. The left part of Figure 1 shows the lower cloud levels of Venus captured by the IR2 camera. Note the almost symmetrical giant streaks across the northern and southern hemispheres. Each streak is hundreds of kilometers wide and stretches diagonally almost 10,000 kilometers across. This pattern was revealed for the first time by the IR2 camera, and the team have named it a planetary-scale streak structure. This scale of streak structure has never been observed on Earth, and could be a phenomenon unique to Venus. Using the AFES-Venus high-resolution simulations, the team reconstructed the pattern (Figure 1 right-hand side). The similarity between this structure and the camera observations prove the accuracy of the AFES-Venus simulations.

Figure 1: (left) the lower clouds of Venus observed with the Akatsuki IR2 camera (after edge-emphasis process). The bright parts show where the cloud cover is thin. You can see the planetary-scale streak structure within the yellow dotted lines. (right) The planetary-scale streak structure reconstructed by AFES-Venus simulations. The bright parts show a strong downflow. (Partial editing of image in the Nature Communications paper. CC BY 4.0)

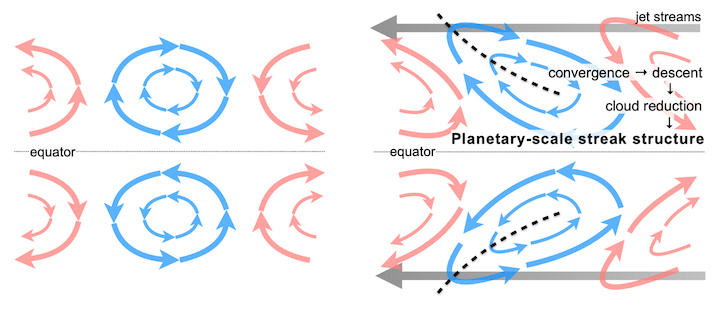

Next, through detailed analyses of the AFES-Venus simulation results, the team revealed the origin of this giant streak structure. The key to this structure is a phenomenon closely connected to Earth’s everyday weather: polar jet streams. In mid and high latitudes of Earth, a large-scale dynamics of winds (baroclinic instability) forms extratropical cyclones, migratory high-pressure systems, and polar jet streams. The results of the simulations showed the same mechanism at work in the cloud layers of Venus, suggesting that jet streams may be formed at high latitudes. At lower latitudes, an atmospheric wave due to the distribution of large-scale flows and the planetary rotation effect (Rossby wave) generates large vortexes across the equator to latitudes of 60 degrees in both directions (figure 2, left). When jet streams are added to this phenomenon, the vortexes tilt and stretch, and the convergence zone between the north and south winds forms as a streak. The north-south wind that is pushed out by the convergence zone becomes a strong downward flow, resulting in the planetary-scale streak structure (figure 2, right). The Rossby wave also combines with a large atmospheric fluctuation located over the equator (equatorial Kelvin wave) in the lower cloud levels, preserving the symmetry between hemispheres.

Figure 2: The formation mechanism for the planetary-scale streak structure. The giant vortexes caused by Rossby waves (left) are tilted by the high-latitude jet streams and stretch (right). Within the stretched vortexes, the convergence zone of the streak structure is formed, a downflow occurs, and the lower clouds become thin. Venus rotates in a westward direction, so the jet streams also blow west.

This study revealed the giant streak structure on the planetary scale in the lower cloud levels of Venus, replicated this structure with simulations, and suggested that this streak structure is formed from two types of atmospheric fluctuations (waves), baroclinic instability and jet streams. The successful simulation of the planetary-scale streak structure formed from multiple atmospheric phenomena is evidence for the accuracy of the simulations for individual phenomena calculated in this process.

Until now, studies of Venus’ climate have mainly focused on average calculations from east to west. This finding has raised the study of Venus’ climate to a new level in which discussion of the detailed three-dimensional structure of Venus is possible. The next step, through collaboration with Akatsuki and AFES-Venus, is to solve the puzzle of the climate of Earth’s twin Venus, veiled in the thick cloud of sulfuric acid.

Quelle: Kobe University

----

Update: 13.01.2019

.

Giant pattern discovered in the clouds of planet Venus

Infrared cameras and supercomputer simulations break through Venus' veil

A Japanese research group has identified a giant streak structure among the clouds covering planet Venus based on observation from the spacecraft Akatsuki. The team also revealed the origins of this structure using large-scale climate simulations. The group was led by Project Assistant Professor Hiroki Kashimura (Kobe University, Graduate School of Science) and these findings were published on January 9 in Nature Communications.

Venus is often called Earth’s twin because of their similar size and gravity, but the climate on Venus is very different. Venus rotates in the opposite direction to Earth, and a lot more slowly (about one rotation for 243 Earth days). Meanwhile, about 60 km above Venus’ surface a speedy east wind circles the planet in about 4 Earth days (at 360 km/h), a phenomenon known as atmospheric superrotation.

The sky of Venus is fully covered by thick clouds of sulfuric acid that are located at a height of 45-70 km, making it hard to observe the planet’s surface from Earth-based telescopes and orbiters circling Venus. Surface temperatures reach a scorching 460 degrees Celsius, a harsh environment for any observations by entry probes. Due to these conditions, there are still many unknowns regarding Venus’ atmospheric phenomena.

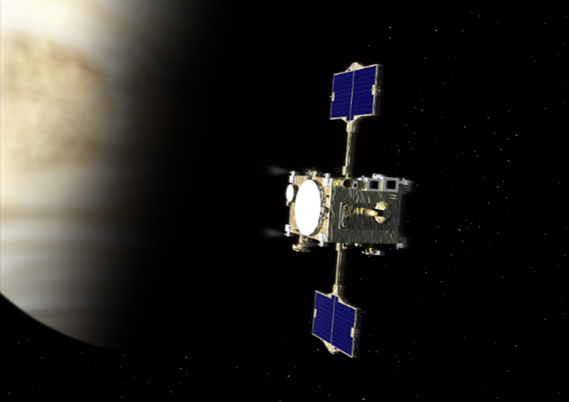

To solve the puzzle of Venus’ atmosphere, the Japanese spacecraft Akatsuki began its orbit of Venus in December 2015. One of the observational instruments of Akatsuki is an infrared camera “IR2” that measures wavelengths of 2 μm (0.002 mm). This camera can capture detailed cloud morphology of the lower cloud levels, about 50 km from the surface. Optical and ultraviolet rays are blocked by the upper cloud layers, but thanks to infrared technology, dynamic structures of the lower clouds are gradually being revealed.

Before the Akatsuki mission began, the research team developed a program called AFES-Venus for calculating simulations of Venus’ atmosphere. On Earth, atmospheric phenomena on every scale are researched and predicted using numerical simulations, from the daily weather forecast and typhoon reports to anticipated climate change arising from global warming. For Venus, the difficulty of observation makes numerical simulations even more important, but this same issue also makes it hard to confirm the accuracy of the simulations.

AFES-Venus had already succeeded in reproducing superrotational winds and polar temperature structures of the Venus atmosphere. Using the Earth Simulator, a supercomputer system provided by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), the research team created numerical simulations at a high spatial resolution. However, because of the low quality of observational data before Akatsuki, it was hard to prove whether these simulations were accurate reconstructions.

This study compared detailed observational data of the lower cloud levels of Venus taken by Akatsuki’s IR2 camera with the high-resolution simulations from the AFES-Venus program. The left part of Figure 1 shows the lower cloud levels of Venus captured by the IR2 camera. Note the almost symmetrical giant streaks across the northern and southern hemispheres. Each streak is hundreds of kilometers wide and stretches diagonally almost 10,000 kilometers across. This pattern was revealed for the first time by the IR2 camera, and the team have named it a planetary-scale streak structure. This scale of streak structure has never been observed on Earth, and could be a phenomenon unique to Venus. Using the AFES-Venus high-resolution simulations, the team reconstructed the pattern (Figure 1 right-hand side). The similarity between this structure and the camera observations prove the accuracy of the AFES-Venus simulations.

Next, through detailed analyses of the AFES-Venus simulation results, the team revealed the origin of this giant streak structure. The key to this structure is a phenomenon closely connected to Earth’s everyday weather: polar jet streams. In mid and high latitudes of Earth, a large-scale dynamics of winds (baroclinic instability) forms extratropical cyclones, migratory high-pressure systems, and polar jet streams. The results of the simulations showed the same mechanism at work in the cloud layers of Venus, suggesting that jet streams may be formed at high latitudes. At lower latitudes, an atmospheric wave due to the distribution of large-scale flows and the planetary rotation effect (Rossby wave) generates large vortexes across the equator to latitudes of 60 degrees in both directions (figure 2, left). When jet streams are added to this phenomenon, the vortexes tilt and stretch, and the convergence zone between the north and south winds forms as a streak. The north-south wind that is pushed out by the convergence zone becomes a strong downward flow, resulting in the planetary-scale streak structure (figure 2, right). The Rossby wave also combines with a large atmospheric fluctuation located over the equator (equatorial Kelvin wave) in the lower cloud levels, preserving the symmetry between hemispheres.

This study revealed the giant streak structure on the planetary scale in the lower cloud levels of Venus, replicated this structure with simulations, and suggested that this streak structure is formed from two types of atmospheric fluctuations (waves), baroclinic instability and jet streams. The successful simulation of the planetary-scale streak structure formed from multiple atmospheric phenomena is evidence for the accuracy of the simulations for individual phenomena calculated in this process.

Until now, studies of Venus’ climate have mainly focused on average calculations from east to west. This finding has raised the study of Venus’ climate to a new level in which discussion of the detailed three-dimensional structure of Venus is possible. The next step, through collaboration with Akatsuki and AFES-Venus, is to solve the puzzle of the climate of Earth’s twin Venus, veiled in the thick cloud of sulfuric acid.

Figure 1: (left) the lower clouds of Venus observed with the Akatsuki IR2 camera (after edge-emphasis process). The bright parts show where the cloud cover is thin. You can see the planetary-scale streak structure within the yellow dotted lines. (right) The planetary-scale streak structure reconstructed by AFES-Venus simulations. The bright parts show a strong downflow. (Partial editing of image in the Nature Communications paper. CC BY 4.0

-

Figure 2: The formation mechanism for the planetary-scale streak structure. The giant vortexes caused by Rossby waves (left) are tilted by the high-latitude jet streams and stretch (right). Within the stretched vortexes, the convergence zone of the streak structure is formed, a downflow occurs, and the lower clouds become thin. Venus rotates in a westward direction, so the jet streams also blow west.

Quelle: JAXA

----

Update: 20.09.2025

.

Venus Climate Orbiter “AKATSUKI” Operation Completed

Akatsuki was launched from the Tanegashima Space Center on May 21, 2010, aboard the H-IIA Launch Vehicle No. 17. The spacecraft successfully entered Venus orbit in December 2015, becoming Japan's first planetary orbiter beyond Earth. Since then, Akatsuki continuously observed Venus's atmosphere for more than eight years. The mission’s scientific achievements focussed on planetary meteorology and included the discovery of the largest mountain wave (stationary gravity waves) in the Solar System, the elucidation of the mechanism that maintained high-speed atmospheric circulation (super-rotation) around Venus, and the application of data assimilation techniques (popular in Earth's meteorological research) to Venus for the first time.

Communication with “Akatsuki” was lost during operations near the end of April 2024, triggered by an incident in a control mode of lower-precision attitude maintenance for a prolonged period. Although recovery operations were conducted to restore communication, there has been no luck so far. Considering the fact that the spacecraft has aged, well exceeding its designed lifetime, and was already in the late-stage operation phase, it has been decided to terminate operations.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to all the organizations and individuals who have cooperated and supported the development and operation of Akatsuki.

Reference 1:

Major Achievements and Results of Akatsuki

For details on the major achievements and results of Akatsuki, please refer to the following materials: the Space Development and Utilization Division report, the press briefing materials, and the Akatsuki team website.

- November 29, 2018: Space Development and Utilization Division reportExternal Link(site: Japanese only)

- November 19, 2019: Press Briefing on Observation Results from the Venus Probe “Akatsuki”(site: Japanese only)

- “Akatsuki” Team Web Page

Reference 2:

Overview

| Launch | May 21, 2010, 6:58 AM (JST) | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Mass | Approx. 520 kg (at launch) |

| Outline | Rectangular prism: 1.0 m x 1.5 m x 1.4 m Paddles: 1.0 m x 1.4 m (2 wings)  |

|

| Orbit | Altitude | Periapsis: Approx. 1,000 km Apoapsis: Approx. 360,000 km |

| Type | Elliptical orbit around Venus | |

| Period | Approx. 11 days | |

| Primary Mission Instruments | 1 µm camera (IR1) 2 µm camera (IR2) Long-wave InfraRed camera (LIR) Ultraviolet Imager (UVI) Lightning and Airglow Camera (LAC) Ultra-Stable Oscillator (USO) |

|