22.12.2017

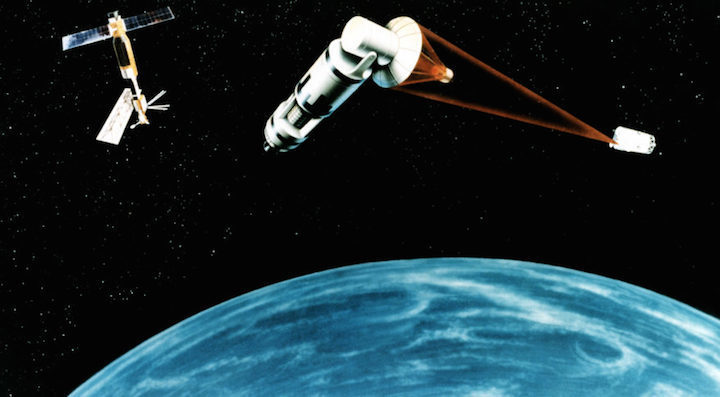

WASHINGTON — It’s one of those ideas that never really goes away: The deployment of missiles in space to intercept ballistic missiles aimed at the United States and its allies. With North Korea testing ever more advanced nuclear weapons and delivery systems, the push to place interceptors in space is back in the conversation.

Congress is asking the Pentagon to investigate the possibility. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 authorizes the development of a “space-based ballistic missile intercept layer, capable of providing boost-phase defense.”

Don’t do it, warns a new report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. The think tank included space-based missile interceptors as part of its series titled “Bad Ideas in National Security.”

This would be an attempt to resurrect the high-tech missile shield derided with the moniker ‘Brilliant Pebbles’ during the George H.W. Bush administration. The idea somehow has resurfaced after a hibernation period between Republican administrations, wrote Thomas Roberts, program coordinator and research assistant for the Aerospace Security Project at CSIS.

“Space-based missile interceptors are a bad idea because of their inefficiency and vulnerability,” said Roberts. “Investments in missile defense would be better directed to other, more effective areas.”

From a political standpoint, the consequences of a space-based missile interceptor system would be troubling, Roberts said, as such a system would be seen as overt weaponization of space.

Defending against a missile strike during the boost-phase is generally preferred but it presents the same challenge to space-based interceptors as it does for ground-based ones: having an interceptor close enough to the missile to respond when one is launched, Roberts explained. “The physics of orbital mechanics dictates that only interceptors in low-Earth orbit can reach a target missile in the required response time for a boost phase intercept — about 120 and 170 seconds for solid-and liquid-propelled missiles respectively.”

Satellites in LEO are in constant movement over the surface of the Earth, meaning a large constellation of satellites is needed to ensure at least one is within range of a particular place on Earth at all times, Roberts noted. While satellites in geostationary orbit stay fixed over one area, at an altitude of more than 22,000 miles, they are simply too far away for an interceptor to reach a missile while it’s still in its boost phase.

To defend against multiple missiles being launched at the same time — a salvo attack — several weapons must be within intercept range to provide effective coverage. Having a minimum of one interceptor available to strike a missile would require a constellation of hundreds of space-based interceptors, Roberts argued. Having multiple interceptors in position to defend against multiple missiles would mean thousands of interceptors in orbit. He cited a 2004 study by the American Physical Society suggesting that 1,646 satellites would be required for full-Earth coverage. The cost of such a system is estimated at $67 billion to $109 billion.

One inherent weakness of a space-based missile shield is that the use of even a single interceptor can undermine the effectiveness of the remaining interceptors, Roberts noted. An adversary could both launch a missile to create a gap and later launch a second missile through the gap. Filling gaps in coverage would require back-up interceptors in orbit, waiting to take the place of an expended one, or the ability to launch new interceptors with short notice. These options would require a substantially greater investment than a minimal satellite constellation.

Roberts said space-based interceptors could contribute to the greater missile defense complex by “thinning the herd” in a ballistic missile attack. But the physical constraints inherent to a boost phase intercept from orbit make it an impractical system to defend the United States and its allies. Investments in missile defense, he contends, would be better spent on adding a space-layer for tracking and target discrimination or additional land- and sea-based interceptors. The Outer Space Treaty does not prohibit placing conventional weapons like missile interceptors in space, as it does for nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction in general. “But the fact that it is not prohibited does not make it a good idea.”

Quelle: SN