21.12.2017

When complete, the ELT dome will stand almost 262 feet (80 meters) high atop Cerro Armazones, a 1.8-mile-high (3 kilometers) mountain in the Sierra Vicuña Mackenna section of the Chilean Coast Range in the Atacama Desert, where the instrument will face rigorous winds. [The Biggest Telescopes on Earth: How They Measure Up]

"These conditions present an engineering challenge, making wind-tunnel tests vital," ESO officials explained in a new video.

Credit: ESO

-

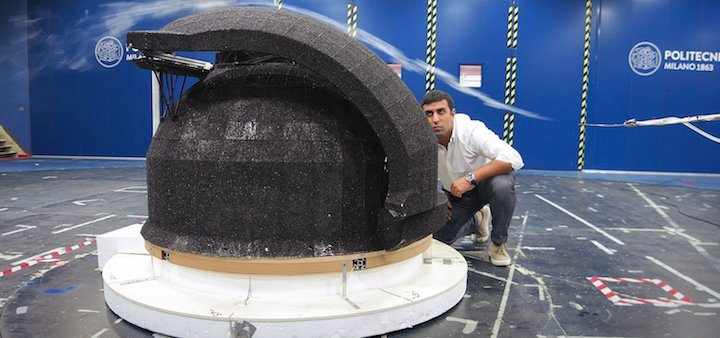

During the tests, a model of the ELT faced blustery conditions in a wind tunnel at the Polytechnic University of Milan in Italy. It was plastered with sensors to measure the structural load it could face.

"The wind-tunnel test is developed to reproduce the conditions that the ELT will face when it's operational," said engineer Luca Ronchi in a blog post, "so, basically, it's about reproducing the dome and telescope on a smaller scale (made of glass-fiber-reinforced plastic), equipping it with sensors, calibrating these sensors, placing the object in the wind tunnel and — according to the established and agreed-upon test program — reproducing the conditions that the ELT will actually face on top of Cerro Armazones."

When complete, the Extremely Large Telescope will use a colossal, 128-foot (39 m) primary mirror, made up of 798 hexagonal mirror segments, to survey the universe like never before.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 21.12.2023

.

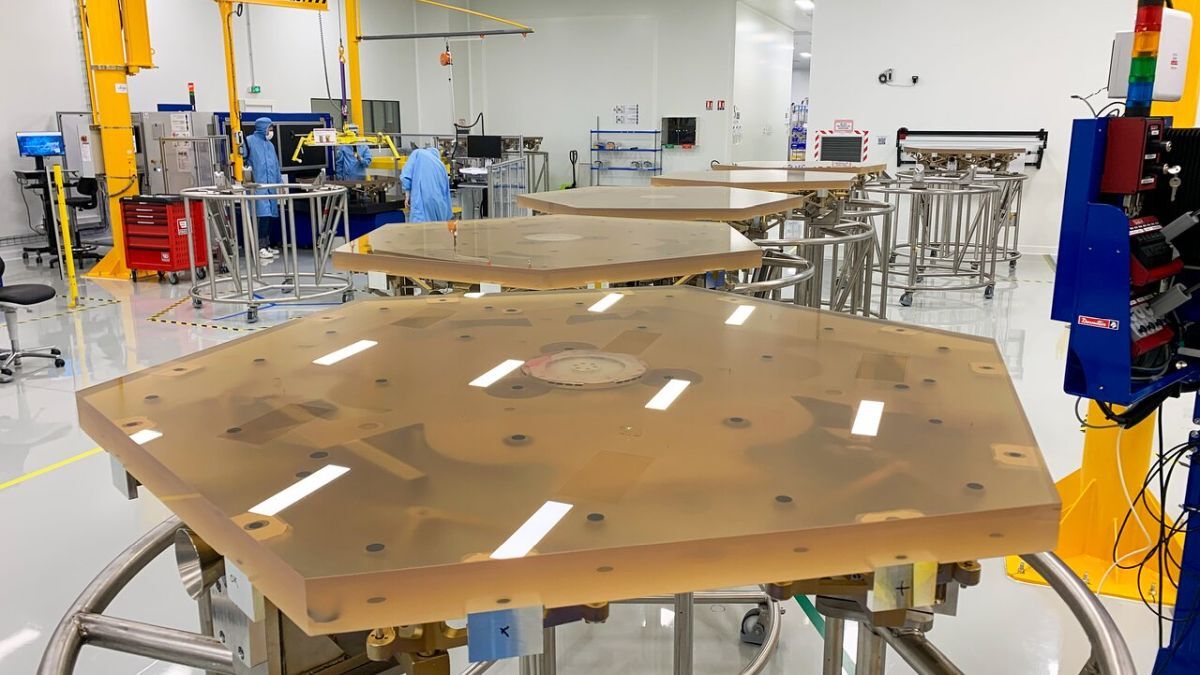

Primary mirror, M1, segments of ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) awaiting finishing at Safran Reosc facilities in France. 798 hexagonal segments will work together on the ELT, acting as one giant mirror 39-metres across. Credit: Safran, handout

The first 18 segments of the world’s largest telescope are en route to Chile in preparation for what will be one of astronomy’s biggest constructions on record.

Once complete, the European Southern Observatory’s Extremely Large Telescope (yes, that’s what it’s called) will be the biggest optical and near-infrared ground-based telescope. The project has been in development for nearly 20 years, with construction approved a decade ago.

It is due to come online in 2028.

The assembly of the telescope’s massive mirrors will take place over the next 4 years. This week, the first segments of what will be the main mirror – called ‘M1’ – arrived in Chile.

In total, M1 will consist of 798 mirrors assembled into an almost 40-metre-wide lens.

Before their arrival, these smaller mirrors had their imperfections atomically polished out by French optical systems manufacturer Safran Reosc by ‘sweeping’ their surface with a beam of ions that eat away at the irregularities. Any remnant flaws are no more than 10 nanometres wide – about the size of a biological cell membrane.

The remaining 780 pieces of M1 will be polished and shipped in the coming months, around 4 segments are being prepared each week by Safran Reosc.

The Extremely Large Telescope will be built in the Atacama Desert in the north of Chile, which is one of the darkest skies in the world.

Quelle: COSMOS

----

Update: 20.01.2025

.

The mighty telescope is expected to see its "first light" by 2028.

ESO's Extremely Large Telescope under construction in the Atacama desert in January 2025. (Image credit: ESO/G. Vecchia)

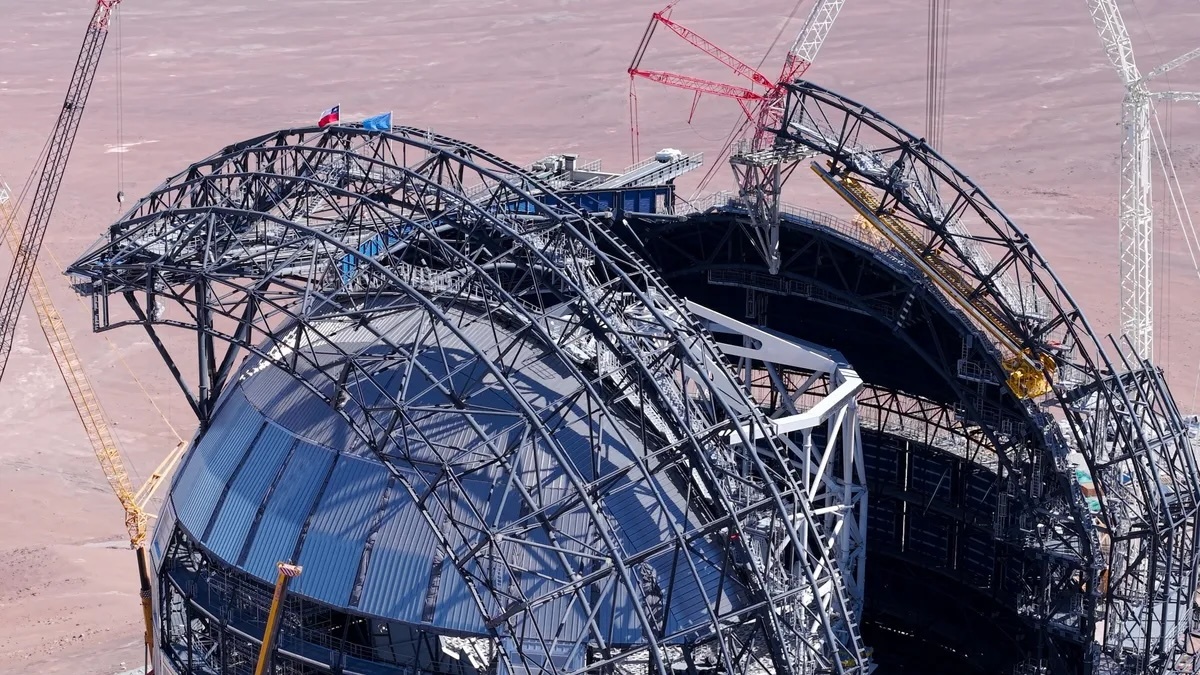

The frame of the dome that will house the world's largest telescope has been completed, marking another key milestone in the observatory's construction.

The European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) — the world's largest visible- and infrared-light telescope — is currently under development on the Cerro Armazones mountain in Chile's Atacama Desert. The mighty telescope is expected to see its "first light" by 2028.

New photos from the ESO show that the dome's frame is now completed, while the outer shell that will fully enclose the telescope is still under construction. Plates of aluminum will be added to the exterior of the frame to protect the telescope from the extreme environment of the Atacama desert, including variable temperatures, according to a statement from the observatory.

The dome measures 305 feet (93 meters) in diameter, or about the size of a football field and stands 263 feet (80 meters) tall. The dome will house the ELT, which aims to observe terrestrial exoplanets and their atmospheres, as well as measuring the expansion of the universe.

ESO's Extremely Large Telescope under construction in the Atacama desert in January 2025. (Image credit: ESO/G. Vecchia

The latest progress photos taken in January 2025 show cranes busy at work installing the outer aluminum layers, also known as cladding. Part of the dome will have large sliding doors, which will remain closed during the day and open at night, allowing the telescope to survey the sky.

Progress has also been made on the polygon structure at the base inside of the dome that will support the telescope's main mirror (M1), and on the "spider" structure on top of it, which will hold the secondary mirror (M2) in the center. M1 will measure a whopping 128 feet (39 meters) across, while M2, which is expected to be completed later this year, will measure 14 feet (4.25 meters) in diameter. The telescope will have three smaller mirrors, for a total of five once complete.

ESO also shared an up-close view of the inner frame of the "spider" structure, named for its arching shape poised above the base, with six arms reaching out from its center. While the skeleton itself is complete, it is waiting to receive all of the individual segments that will make up the five mirrors. M1 alone will consist of 798 glass ceramic hexagonal segments, each of which measure about 2 inches (5 centimeters) thick and about 5 feet (1.5 meters) across. When fully assembled, M1 will be the largest mirror ever built for an optical telescope.

The central tower below the "spider" structure will support the ELT's remaining three mirrors. These components — the central tower, spider structure and polygon base — are all hosted on what is called the altitude structure. This metal frame stands 164 feet (50 meters) tall and is designed to carry all 5 mirrors of the ELT and rotate so that the telescope can be pointed at different parts of the sky.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 25.04.2025

.

The massive dome measures 305 feet (93 meters) in diameter, or about the size of a football field and stands 263 feet (80 meters) tall.

Construction of the world's largest telescope has reached its highest point with assembly of the roof's dome and large sliding doors that will shield the observatory.

The European Southern Observatory (ESO) recently shared new progress photos of the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), the world's largest visible- and infrared-light telescope. The ELT is currently under development on the Cerro Armazones mountain in Chile's Atacama Desert and expected to see its "first light" by 2028.

ESO shared a stunning view of the ELT's construction, including one with a gorgeous, glowing sun rising up behind the telescope on April 12. The photo was taken by Eduardo Garcés from the Cerro Paranal mountain, home to ESO's Very Large Telescope, which is about 14 miles (23 kilometers) from the ELT, capturing a silhouette of the dome's structure surrounded by construction equipment.

The ELT reached a significant milestone recently with the completion of one of the dome's sliding doors — and assembly started on the second — marking the highest point of the dome's construction, according to a statement from the ESO.

ESO and Chilean flags were placed at the top of the telescope's dome as part of a Topping Out or Roofing Ceremony (called Tijerales in Chile) held on April 16, which included a traditional barbecue for workers on site and was live-streamed for industrial and institutional partners celebrating the milestone in Garching, Germany, according to the statement.

ESO shared an up-close view of the dome's roof structure and two flags streaming in the wind, which can produce powerful gusts in the Atacama desert. The two sliding doors located on the dome's roof open laterally and are designed to protect the telescope from the harsh desert environment. They will be closed during the day to shield the telescope from unwanted light and open at night for astronomical observations. The dome also includes a mechanism to seal the interior, preventing wind, rain, dust, and light from entering.

ESO and Chilean flags atop the Extremely Large Telescope's construction site on Cerro Armazones. (Image credit: ESO/CHEPOX)

Garcés took a similar photo in August 2023, which shows a more skeletal frame of the dome without its protective cladding and underscores how construction has progressed in less than two years.

Another recent progress photo taken on April 14 using one of the live webcams on site captured the bright Milky Way flowing above the telescope's dome, illuminated by stars shining in the night sky. Peeking out through the open roof is the white frame of the telescope's main structure that will support its optical equipment, including its primary mirror that measures 128 feet (39 meters) across — the largest ever made for an optical telescope.

The Milky Way shines above the construction site of ESO's Extremely Large Telescope in Chile's Atacama Desert. (Image credit: ESO)

The massive dome measures 305 feet (93 meters) in diameter, or about the size of a football field and stands 263 feet (80 meters) tall. Featuring a 130-foot-wide (39.3m) mirror, the ELT will study the universe in visible light to provide a more detailed view of potentially habitable exoplanets, the formation of the first galaxies, supermassive black holes, and the nature of dark matter and dark energy.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 14.05.2025

.

The 90-meter-wide dome of ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope is nearing completion on the 3,046-meter-high summit of Cerro Armazones in northern Chile.

Govert Schilling

It’s a weird sight. On a 3,046-meter-high (9,993 feet) mountaintop in the desolate Atacama Desert sits what looks like a shiny steel marble, large enough to be visible from tens of kilometers away. I’ve seen it many times before, but always in artist’s impressions and computer renderings. This time, it’s for real. I’m approaching the giant spherical enclosure of the largest optical telescope in the history of mankind.

When Dutch spectacle maker Hans Lipperhey invented the telescope in the early 17th century, he realized that bigger optics would yield better results. But back then, no one could have imagined something as monstrous as the Extremely Large Telescope, under construction by the European Southern Observatory (ESO). With a primary mirror 39.2 meters (129 feet) wide, the ELT will have more light-collecting power than all previous professional telescopes in history put together. Yes, it sounds incredible, but I checked the math, and it’s really true.

I’m joining a Chilean TV crew on a two-hour visit of Cerro Armazones, the location of the ELT. Armazones lies just 20 kilometers (12 miles) east of ESO’s Paranal Observatory, home to the 25-year-old Very Large Telescope (VLT). In an administration building a few hundred meters below the summit, we are provided with hard hats, safety shoes, and reflective vests. Next, our host, ESO’s Sofía Otero, takes us to the observatory site, which is buzzing with building activity.

Safety coordinator Luigi Pinto, of the Italian consortium that is building the telescope, takes us on a tour around the 90-meter-diameter dome, which is about half-finished. Huge cranes have put the first elements of the dome’s two giant doors in place. “Here’s part of the second door,” Pinto says, while walking around a complicated curved steel structure as large as a bridge. “In fact, one of the previous jobs that I worked on was a large bridge. To me, there’s not that much difference.”

After entering the building, we climb a number of stairways to a high gallery, which runs all the way around the inside of the dome. From here, the view is even more impressive. The white telescope structure, consisting of dozens of interconnected steel tubes, and still surrounded by scaffolding, is nearing completion. It is so large that I have difficulty in perceiving the right scale. Trucks and forklifts that drive around on the concrete floor down below look as small as toy cars.

Pinto points to a technician in an orange overall, who is working inside the telescope, almost too small to discern. “He sits at the level where the primary mirror will be,” he says. “But of course, the mirror segments will only be installed when everything else is ready.” The giant primary will consist of a staggering 798 hexagonal segments, manufactured in Germany. “I believe some 200 of them have already been delivered,” says Pinto.

That evening, at neighboring Paranal Observatory, I meet Guillaume Blanchard, the head of ESO’s optical group, who confirms Pinto’s guess. “If you want, I can take you into the ELT Technical Facility tonight,” he says. “That’s where the mirror segments are tested, coated, and stored.” In fact, there will be 931 segments in the end — 133 spares of various curvatures are needed to keep the mirror complete during the continuous recoating process. “If we want to re-aluminize the whole mirror once every two years, we need to take out and recoat two segments per day,” explains Blanchard.

After dinner, we walk toward a large, rectangular building. Inside is the testing and coating facility, which is relatively small, since the mirror segments are just some 1.5 meters wide. The whole lab is a clean room, so I’m not allowed to enter, but through a large window, I can see one shiny hexagon on a test bench, ready to have its quality checked.

Next, Blanchard takes me into another, much larger room. When he turns on the light, I’m flabbergasted. I’m in a giant warehouse, with meters-high storage racks. Large, flat metal crates fill about one-fifth of the total storage capacity. Every crate, uniquely identified by a QR code, contains a single mirror segment. Around me is the largest telescope mirror in the world, in pieces. About once per month, a new truckload arrives.

When we walk back to Paranal’s Residencia, it’s utterly dark outside. Blanchard looks up to the night sky, with an upside-down Orion high above the northern horizon. Even after working with the largest telescopes in the world for many years, the naked-eye view never ceases to amaze and inspire him, he says. “This is really one of the best places on the planet to do astronomy.”

Unfortunately, that discerning quality is soon to be challenged. Earlier that day, Ortego told me about the plans of AES Andes — a subsidiary of an American energy company — to build a “green hydrogen plant” as large as a small city, just 11 kilometers south of the VLT and 20 kilometers southwest of Cerro Armazones. According to a recent ESO study, the facility, with huge numbers of wind turbines and solar panels, would produce air turbulence, vibrations, and dust contamination, and lead to a 35% increase in light pollution.

“Nothing is definitive yet,” says Ortego (the proposed site still has to be approved by the Chilean government), “but we really need to have our voice heard. I just don’t understand why they couldn’t choose another location.” Three weeks after my visit, an ESO press release states that the impact of the facility would be “devastating and irreversible.”

When I drive away from Cerro Armazones, eventually heading north to Arica, where my six-week Chile road trip comes to an end, I keep seeing the dome of the Extremely Large Telescope in my rearview mirror, surrounded by tower cranes. Some four years from now, humankind’s biggest eye on the sky will start observing the universe, hopefully unhindered by industrial activity. I’m looking forward to returning to this astronomical paradise to attend the telescope’s inauguration.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope

----

Update: 9.12.2025

.

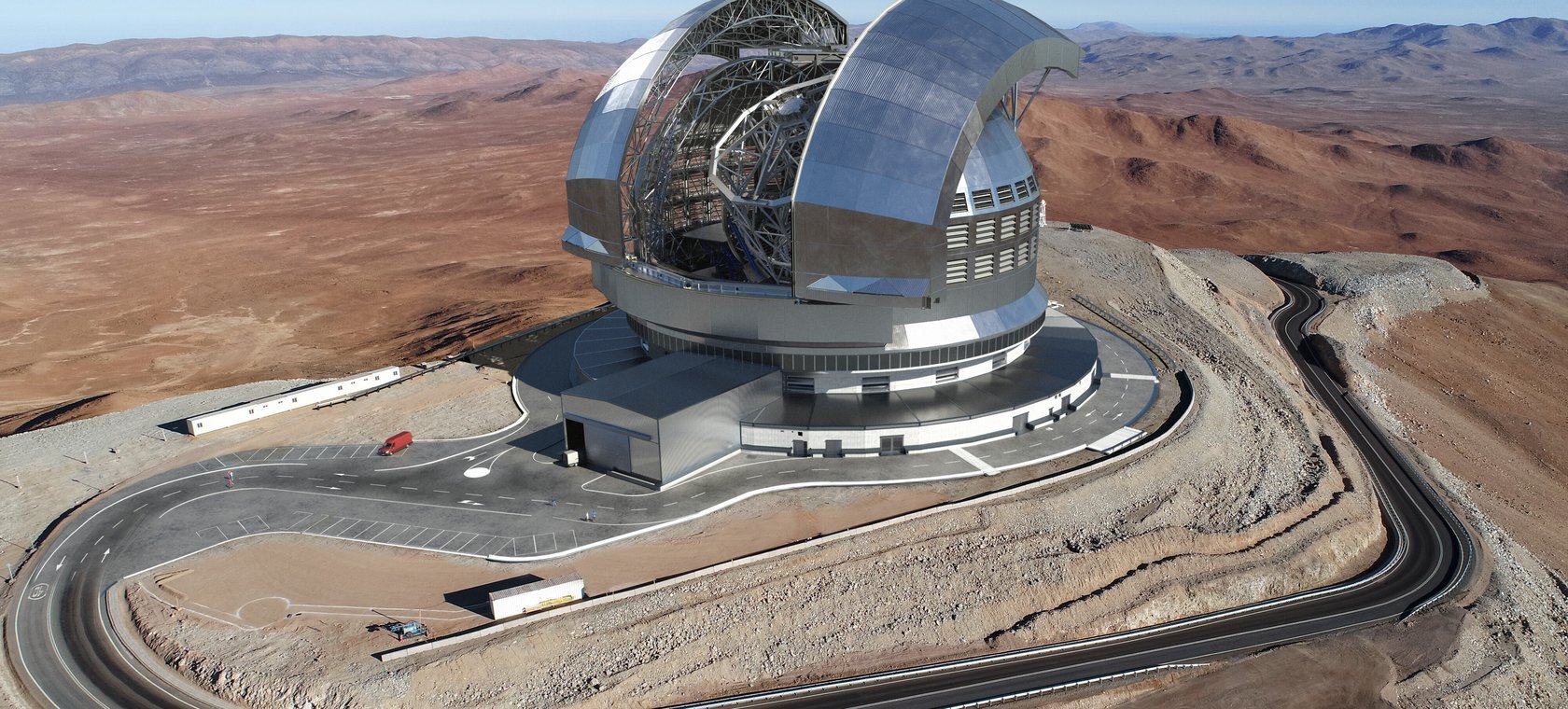

Artist’s impression of the Extremely Large Telescope.

Credit: ESO

Today, the European Southern Observatory ESO has signed an agreement with a large international consortium for the design and construction of the Multi-Object Spectrograph (MOSAIC), an instrument for the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). On what will be the world's largest optical telescope, MOSAIC will simultaneaously measure the light from hundreds of astronomical sources and by that trace the growth of galaxies and the distribution of matter from the Big Bang to the present day. As a consortium member, the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) is responsible for part of the technical development of MOSAIC, as well as for preparing its scientific use.

"We are delighted that AIP, with its many years of expertise in multi-object spectroscopy, will be contributing to key work packages of MOSAIC. Our task is to develop and build the complex optical fibre system that will guide the starlight from the telescope to the spectrographs," says Dr Andreas Kelz, head of the 3D and Multi-Object Spectroscopy department at the AIP.

The agreement was signed by ESO’s Director General Xavier Barcons and Alain Schuhl, the Deputy CEO for Science at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), the institution leading the MOSAIC consortium. Also in attendance were Alexandre Vulic [TBC], the Consul General of France in Munich, and the MOSAIC Principal Investigator Roser Pello from Marseille Astrophysics Laboratory and Co-Principal Investigator Mathieu Puech from the Paris Observatory, in addition to other dignitaries from ESO, CNRS and the MOSAIC consortium. The signing took place at the ESO Headquarters in Garching, Germany.

MOSAIC is a powerful spectrograph: an instrument that splits light into its component wavelengths, so astronomers can determine important properties of astronomical objects, such as their chemical composition or temperature. The instrument will use the widest possible field of view provided by the ELT, operating in both visible and near-infrared light, and will be able to analyse the light for more than two hundred objects simultaneously.

"MOSAIC will conduct the first exhaustive inventory of matter in the early Universe, lifting the veil on how matter is distributed within and between galaxies and greatly advancing our understanding of how present-day galaxies formed and evolved.", explains Dr Davor Krajnović, the AIP representative on the MOSAIC science team and a coordinator of the consortium science working group “Inventory of matter”. “It is a versatile instrument allowing studies of the first galaxies and the intergalactic medium, star formation and chemical enrichment histories, mass assembly of galaxies, dark matter, transient phenomena and discovering electromagnetic counterparts of multi-messenger events”.

ESO’s ELT is currently under construction in Chile’s Atacama Desert, a unique place on Earth to observe the skies.

More Information

The MOSAIC project is developed by an international consortium composed of research institutes in 13 countries, which are:

Quelle: ESO